Day to day pours forth speech,

and night to night declares knowledge.

There is no speech, nor are there words;

their voice is not heard;

yet their voice goes out through all the earth,

and their words to the end of the world.

Psalm 19

There has been no one else in my life like Bill, little as he was in it. Slender and soft spoken, not withdrawn but not forthcoming, had he found himself in a crowded room he would have been the one who called least attention to himself. He did have an eye patch, the result of a childhood accident, but he wore it in such an unselfconscious way that it blended with his reserve. Yet he showed an inward centering that gave him a quiet presence, as if he were in touch with something beyond him, essential and illuminating, that set him apart from the rest of us, and when he looked back you felt he saw you with both eyes. I never heard him speak ill of anyone.

He would explain things, and patiently keep explaining, and treat you as if you were capable of understanding, which is what first drew me. Once, when I was a boy, he told me why the spokes on the wheels of my toy car moving forward appeared to go backward. In the world in which I grew up, defined by roles and ceilings, by the rules of settling down and settling in, he provided a model that helped me wonder what else might be understood and think about where that might take me, to believe that understanding is an engagement worth doing in itself that doesn’t need explanation or purpose, whose reward is the exhilaration of wonder, whose place is the presence that comes from reaching, from grasping. With the presence, the hope some pursuit of my own might return me to a larger, vital world.

He was, in fact, a particle physicist, who devoted his life to the study of the composition of the ultimate parts of nature and the forces that drive them, the understanding that there is no separation between the two but instead a relationship. He would explain that, too, and keep explaining as long as you listened, but it was over our heads and no matter how much he tried to break it down we soon got lost, leaving us with utter bafflement, some of us with skepticism, some of us with suspicion. It is difficult to trust the things we cannot understand, no matter how fundamental.

When I went to Berkeley in the late ’70s, grad school in English, I stayed with Bill a few weeks while I looked for a room. Then I lost touch, as so often happened there. We were all caught up in what we were doing.

Some four years later, midsummer, I got a call from his mother in North Carolina, a distant voice. She was polite and stalling in her desire not to impose and only made brief, oblique reference to Bill, not much more than she hadn’t heard from him in a while. I didn’t know what her concern was or even if there was one. After I hung up it occurred to me she wasn’t sure herself.

So I walked up the hill to his apartment in North Berkeley, but he wasn’t in. I looked in all the windows and nothing stood out. Everything was in place, everything looked as I remembered, everything looked as might have been expected. I debated breaking in, but had no evidence or cause, and was disturbed I even gave it a thought. He simply could have been on vacation. There were other places he might have been. Also I was dealing with a mother’s concern, foremost in mind. I didn’t know her well, and she seemed a little strange on the phone.

Still, I needed to put her at ease. I went back a few days later and saw the same. I started making calls, beginning a search to see what I could learn, not knowing what I was looking for or that I had any reason to look. What I also needed was to settle the doubts I had turned loose within myself.

.

Today, afternoon, midsummer, so many years later, elsewhere, trying to think, to understand, to define a mood or find one, but mind wandering, I look up from my desk and notice before the window a few motes of dust hovering nearly motionless in the still air but not quite, slight reminders of indeterminacy and dissolution, yet, illumined by the sun, bright, tiny specks that break the surface of the ordinary, faintly suggestive, faintly marvelous. Outside the window the foliage from the backyard trees shifts irresolutely in a gentle breeze, a dense, erratic pattern of dark and lighter greens, a constellation of rough-edged, roundish oak leaves, largely rising, and the smooth, long leaves of a walnut and Podocarpus, thin and thinner, largely falling, and of the leaves of the other trees behind them, almost covered. Now, inside, at the corner of the window, a jagged crack suddenly appears—it has always been there but has been forgotten and put aside—that runs to the ceiling like a bolt of lightning, a rip of quick terror, or a rent in the commonplace that opens revelation. Now, outside, flash reflections of the sun on the front leaves, the leaves glaring, nearly white, nearly bleached of detail, bright and blinding, like the rush of shock, or surprise. In only a few gaps among the leaves, small and scattered, can I see the sky. Beyond the sky, all the rest.

The day speaks—

Everything is exactly what it is.

In the beginning—

Or rather 10-43 seconds after the beginning, some 14 billion years ago, according to the standard model, a symmetry breaks and the universe explodes from a size so small that it would be pointless to state it, having a denseness, in comprehension, inversely related to its size. Its energy is 1032 Kelvin, against which the energy of the sun would not provide manageable comparison, but it is cool enough to allow the force of gravity to separate itself from the other forces, though nothing sensible can yet be said about its effects. The energy, however, is still too strong for quarks to join to form neutrons and protons, much less neutrons and protons join to form nuclei, or nuclei to draw free electrons to form atoms, or atoms to join to form molecules and gas clouds and masses and the planets and stars and solar systems and galaxies we now see. Our knowledge of the universe depends on understanding this moment.

The very beginning, zero time, may be beyond the reach of physics. The questions as to what existed before zero time and where the Big Bang took place and what existed beyond may not make sense because this may have been the time that time and space were in the process of being created. Also our common conceptions of time and space are inadequate to explain time and space.

The first step is to find the questions we can ask and learn their terms.

Bill was my uncle’s brother, the brother of the husband of my mother’s sister, thus no blood relation. I’d see him on rare occasions during family trips to my grandmother’s house in a small, crossroads town in rural North Carolina when he visited his brother and family who lived there, back from California, Germany, Switzerland, other distant places. We knew he was there when we saw his Karmann Ghia parked in the dirt drive, for us then an exotic car.

His ascent was meteoric, almost from nowhere. He grew up in rural towns nearby, as small or smaller, then went to NC State where he received near perfect grades and was awarded a Fulbright, which allowed him to study at Heidelberg University in Germany and work at CERN, the nuclear research labs in Switzerland, in preparation for his master’s degree. When he returned to the US he had choices, deciding on Berkeley to get his PhD. No one I knew had gone so far away or risen so high. He broke the mold of expectations.

After his PhD he stayed to continue his research. He had a part-time job at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory and picked up part-time teaching at UC Davis and Berkeley to supplement his income. But his real work still lay elsewhere, further out and further in. The Bevatron at Lawrence had limited experimental use, so when grants came through he went to the more powerful accelerators at Fermilab near Chicago and SLAC at Stanford. That is one reason it was not surprising not to find him the day I walked up the hill.

When I arrived in Berkeley, late summer 1978, I had made arrangements to stay with friends of a friend. I discovered quickly I wasn’t welcome. I called Bill for advice, and in twenty minutes he drove down, now in a Volvo, and helped me load my stuff. I had no cause to expect such care, yet he apologized for not coming sooner.

His apartment, like his dress, was neat, sparse, and functional, though had a few distinctions and showed diversions and other depths. Beneath the stereo, albums of two modern classical musicians in San Francisco, whose performances he helped record. On top of the bookcase, a well-made windup robot, German, I think, a miniature marvel of engineering. On the shelves, among others, books and articles that defended Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, as the author of the Shakespeare opus, which drew from me heavy skepticism, in fact I thought the theory was crazy, but he attempted to explain that too. He was experimenting with making wine and I tried some. I had no opinion; he wasn’t satisfied. There were corner windows in the living room, one which looked out on the bay, the other over the campus. Late afternoons I watched the coastal fog approach, climbing and descending the San Francisco hills, covering the city, the bridge, the bay, some days the school up to the Berkley Hills, with its dense, quiet resolve.

He also gave me a tour of the campus, then the town. The bookstores on Telegraph—Cody’s for new books, where national and international writers read from their work, where wounded protesters once were treated and books by and on Wittgenstein sold well; Moe’s and Shakespeare’s for used, the only places I could find many books I later needed, out of print. The cafés, two floors of Caffe Med, where street life met campus and conversations ran the spectrum. All were crowded at all hours, Telegraph stirring with their traffic. Ideas mattered, and the town radiated the slow burn of minds. Bill had received offers of full-time positions to teach elsewhere but turned them down as the schools didn’t have the facilities and would have taken him from his research and this world. My parents couldn’t understand that decision, or him. I envied his life and began anticipating mine. What he laid out for me was the locus for my own later work.

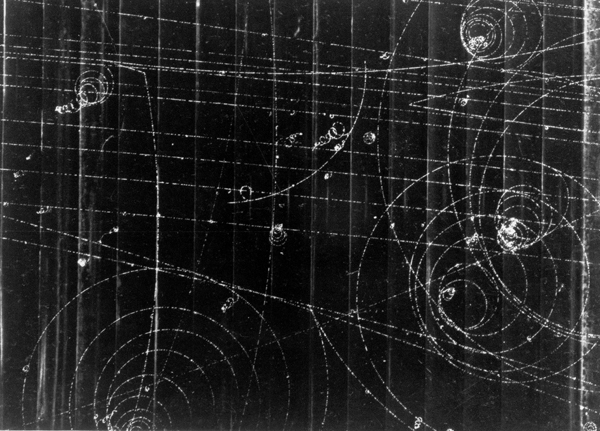

And he took me to his office at Lawrence, where he showed me a picture of a reaction in a bubble chamber from one of his experiments.

At the time quark theory, like the Big Bang, had gained the status of the standard model. He talked about string theory as well, still debated now. We hear these terms, and if we don’t repel from them, maybe they give us a jolt, a push to the side, a moment of disturbance. Or we learn to repeat and use them to spice our talk. Not long ago it was reported that the Higgs boson—the “God Particle”—might have been discovered, whose existence was predicted by theory, the particle that indicates the field that gives other elementary particles their mass, the universe its substance, belief in which still holds today. Sooner or later, however, we let the words slide and move on. What difference do they make? What is lost is how much is involved, how much our certainties are pushed, how much vision itself is challenged, how far we might be taken, further in and further out.

To research particle physics first the body of the theory has to be understood, then experiments designed to confirm or extend it. Teams are formed, proposals written and submitted to get time on the accelerators. At the site accelerators hurl pulses of particles at tremendous energy towards a detector, where collisions are observed. Deflections reveal what exists inside an atom; other particles are released, some of which point to the existence of still others. At SLAC particles are shot two miles at 50 billion volts. The detector Bill used was a bubble chamber, the technology of the time, which was filled with a medium such as liquid hydrogen that the particles struck, where pictures were taken to record the reactions. In one experiment Bill performed at SLAC, 500,000 pictures were taken over a period of three months; other experiments might take tens of millions. Then this mass of data has to be analyzed for the rare, meaningful event. An experiment, start to finish, can take years, even decades.

The scales used to measure the particles defy any scale we can handle. Particles may exist only an impossible fraction of a second and have a size dwarfed by the size of an atom, though at this level of nature physical size does not apply. Yet these particles and their reactions define the universe, and experiments are now being run in the accelerators to simulate its early stages. The forces involved may extend infinitely or only cover a subatomic gap, yet in the latter case the potential energy is enormous. To study particle physics is to learn that everything is almost nothing, yet that almost nothing has universal extending order. The research is a drive towards total grasp. What particle physicists are looking for are the ultimate parts of nature that cannot be broken down further and their single, unifying force.

If we are disposed to wonder, what else better do we have to wonder about? If we want to understand the ultimate nature of reality, this is the direction to go. However difficult it is to fathom the theories, there is nothing arbitrary or fantastic about them. The movement of the stars away from us and each other now points to the Big Bang, whose background radiation has been measured. Particle physics is supported by a century of thought and has been confirmed by experimental observation, the laws of physics, and the coherence of math. The theories are not complete, but whatever comes next will be derived from what is solid and accepted now, or will break from that ground.

What strikes me now, as I look outside my window and stare at the leaves and their bright reflections, is the enormous irony of effort and perception, one that strains that literary deflection. The picture Bill showed me, set against what it revealed, for all the time and effort that went into its creation and selection, was nothing more than white scratches, lines and spirals, on a black field. And those scratches were not the particles themselves but bubble traces caused by their reaction in the liquid gas, their paths guided by a magnetic field in the detector that provided the means for their precise measurement. There is cause for a kind of wonder just in this irony itself.

When I close my eyes, afterimages of glare on leaves.

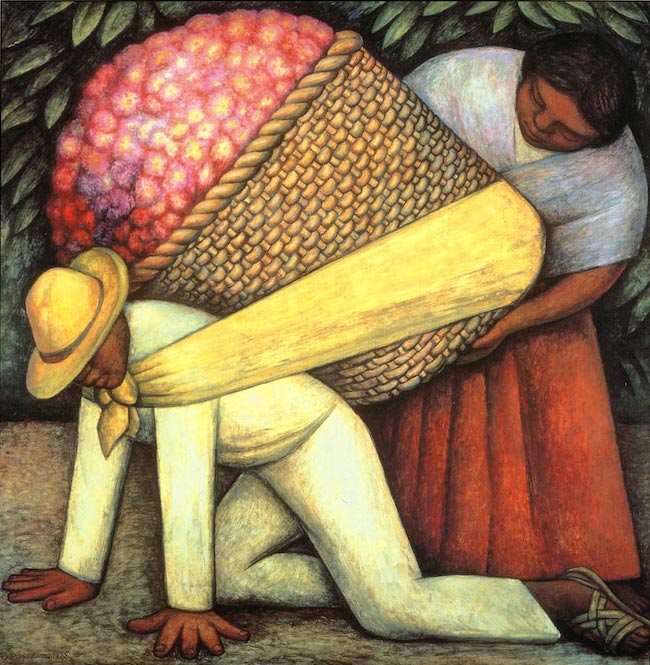

But as great is the marvel that a mind, a man, could be moved to study matters so complex, so essential, who could approach nature on its first terms. It is another kind of wonder, a large part of what makes us human.

What a piece of work is a man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties, in form and moving how express and admirable, in action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god: the beauty of the world, the paragon of animals. . . .

Hamlet.

.

Any investigation will be affected by the influence of the investigator, the tools, the means at his or her disposal, which need to be factored in or filtered out. What assumptions are brought in, what biases? What does one expect to find? Outside influences—noise—also seep in and have to be dealt with as well. The temptation is to invoke Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, but that would not only be an inaccuracy but also a mistake of category.

Uncertainty, however, is what I found. I called Lawrence first and got a colleague who apparently knew Bill fairly well. He was friendly but seemed distant and strange in ways I couldn’t pin down. But I was a stranger, and his reserve might have come from the need to protect what was personal. Also I must have seemed strange myself. I didn’t want to raise alarm because I had no cause, yet still I needed to push some question to continue my search. But I didn’t know what that question was much less how to frame it, so I fumbled for several minutes. My call, in fact, was just like the one I had with Bill’s mother and I realized her dilemma. I’m not sure I didn’t raise concerns about me that may have drawn sympathy, maybe tactful evasion, maybe, likely, doubts. He did give me a few names to call, however, including the musicians in San Francisco.

I made those calls and got similar results, again sensing aloofness and something else in the others I could not identify, again wondering what impression I might have made. But I got more names—a contact at Davis and another woman in Berkeley, who was working on her PhD in classics and was closer to him than the others—and kept calling. The others started making calls themselves, the calls reaching out in a widening circle, those calls among those who knew Bill better, where perhaps private knowledge was shared. Then again, it didn’t appear in my calls that anyone knew much. The only thing that was certain was that no one knew where he was, though all agreed there could have been several reasons for his absence, well within normal expectations.

I also made more trips to his apartment, where all was exactly the same as before, nothing moved, nothing out of place, and again debated breaking in, even more disturbed I thought about doing so. I felt like a spy. And the tension I felt might have come from my own misplaced fears. I was also part of a chain reaction in which I wasn’t sure of my influence. I worried I had violated Bill’s privacy by making calls and asking questions, that I may have raised undue doubts about him among the people in his life. Suspicion is insidious and even in the best of us can grow into a monster. And I had disrupted the working assumption of all of us that keeps our lives in order and sustains us when all is quiet, that we are well, that all is well, that all is as it should be.

I had this troubling thought: if I went away without giving notice, could someone find me? If he or she talked to those I knew, what would they say? What suspicions might be unleashed? What would anyone have to say?

Still it seemed we all moved around something that would not go away, but it was only an object of indefinite shape that could have been the ghost of our uncertainty. Yet after another week we were settled that something was wrong. Reserve melted, barriers broke. The police were called. We opened up and talked frankly and pushed the search, extending the net of our humanity to catch one of us who might have fallen.

.

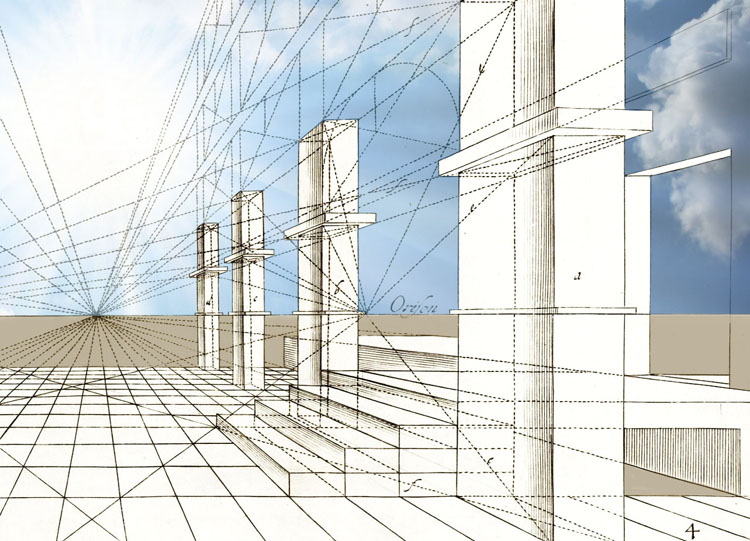

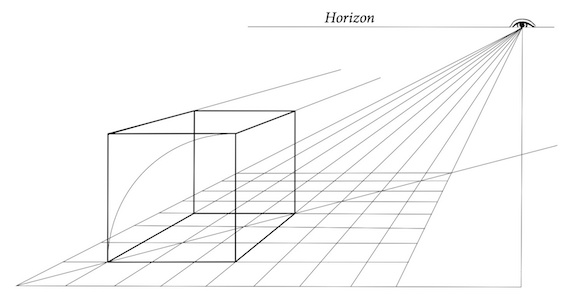

I grew up looking at pictures of order, demonstrations of function and purpose, of meaning, models of the world that located me and reassured. In grade school science texts I saw diagrams of atoms that looked like miniature solar systems, clusters of balls, perfect spheres, neutrons and protons in their nuclei around which smaller balls, electrons, revolved in perfect orbits. I don’t think I ever wondered what kept the nuclei together since their protons had the same positive charge and should have pushed away, why the world did not fly apart. I also saw colorful pictures of our solar system, more balls, more perfect spheres, the nine planets revolving in their orbits around the sun, moons around the planets.

Here on earth I was presented with diagrams of men and women in various uniforms and dress walking between buildings that represented our institutions, who carried a dollar bill or a law to show the orderly workings of our society, of our government, of our economic system. Also pictures of the people here to help, doctors, lawyers, and teachers, entering hospitals and courts and schools. Along with these, pictures of our enterprise, more people moving raw materials from building to building to create finished products and put them in our hands. I saw strings of dollar bills, and of products and other things we made and carried, stretched around the earth or sent to the moon and back to give me some idea of the magnitude of our order. Elsewhere I saw pictures of heaven, a radiance among clouds. On the dollar bill, a pyramid atop which hovered a shining eye.

Somehow all the pictures were of a piece.

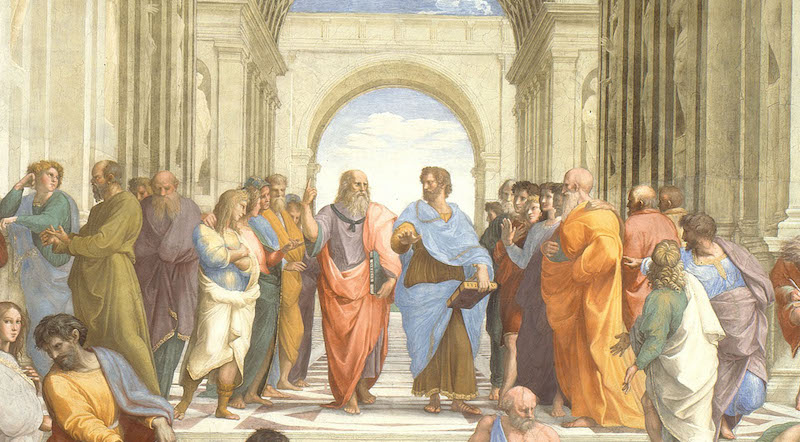

Elizabethans looked at a picture of the world as well:

The heavens themselves, the planets and this centre

Observe degree, priority and place,

Insisture, course, proportion, season, form,

Office and custom, in all line of order;

And therefore is the glorious planet Sol

In noble eminence enthroned and sphered

Amidst the other; whose medicinable eye

Corrects the ill aspects of planets evil,

And posts, like the commandment of a king,

Sans check to good and bad. . . .

Shakespeare.

The Elizabethan picture was based on a cosmic understanding, with earth and us at the center, that located and reassured as well, that established hierarchies of functions and status, a picture that radiated harmony and correspondence throughout, infused with the light of divine inspiration shining upon the royal court.

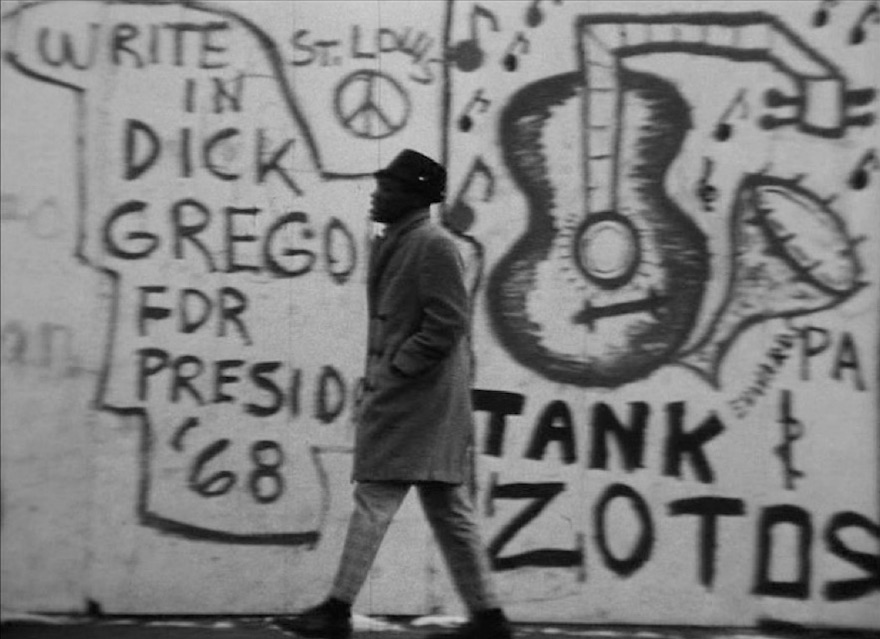

As I got older I was attracted more by pictures that questioned the pictures of order I saw, scathing parodies, distorted, scattered views. The problem, of course, was with who got to wear which uniforms and go to which buildings, with what we were left holding in our hands. I reacted myself in simmering restlessness against their neatness, their constraint, the narrow roles.

None of the pictures, however, early in my life or later, gave much to charge the heart, or the spirit, or whatever we can think to call the part of us we most want to name, something that might move us separately to warmth and fullness, that might bind us together.

Or put us at ease on sleepless nights

Many of us were upset by the discoveries of Planck, Einstein, and the others, whose theories of nature shook the ground on which we stood and disrupted the harmony of solid balls pushing and pulling and revolving against, toward, and around each other. With the shaking, doubts were raised whether anything worthwhile might be built on top. Everything is relative and indeterminate, life is arbitrary, an unleashing of random forces. I suspect, though, we would have come to the same conclusion without physics. We had the evidence of the collisions on the battlefields of the last century as well as elsewhere to unsettle our beliefs.

In a sense, according to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, what scientists find at the atomic level depends on what they’re looking for. They can design an experiment that observes the position of a particle, say an electron, or an experiment that observes its momentum, but they cannot observe both because both cannot be known at the same time. The indefiniteness is not a problem of observers and their assumptions or their equipment, but a matter of the essential nature of electrons themselves, dual and indeterminate. Our solid balls are not solid. Yet either experiment can yield precise, meaningful results. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle is fundamental to quantum mechanics, which provided the foundation for the atomic theory that followed. Physicists embraced the indefinite to develop an understanding more precise and thorough. The new physics did not disrupt the order of the world but brought us closer to what was beyond our vision, strengthening our grasp after classical physics had reached a dead end.

Then again, the desire for order is not the order of desire. The Elizabethan picture is built on gross cosmological error, though many knew otherwise at the time. Metaphorically, however, it is perfectly valid and has value. Our lives can matter, and putting us and our planet at the center reinforces that desire, its force, its possible extension. A context is provided that helps explain the marriage of our actions and our beliefs when all goes well, or at least contain them, and what is wrong when our lives, our world fracture. It does not matter where the planets are. Science helps us understand the world, but metaphors are where we live.

Now older still I tire of being unsettled and uncontained, yet remain restless. I have also begun asking questions that did not concern me when I was younger. What I realize now is that I did not reject the pictures of order I saw because I did not believe in order but because they did not hold the order in which I wanted to believe.

I do not care about chains of command. Power over others, however large its effects, is a sterile study. Still I read Shakespeare for what might be left after aggrandizement is factored out. I want to feel I have a place where I can move among others and be moved alone, where there is a picture of understanding that explains that motion. Even if Shakespeare’s explanations are incomplete, even wrong, at least the possibility of understanding is constructed, and looking at a picture of order moves us to think of other pictures that might help us help each other, and sustain us, and keep us together.

Or help us, on rough nights, to know the place where we will wake up.

Yet I want to believe that pictures are not made up, that there is some connection between them with what I see when I look out.

But a picture of order is only a picture of order.

After another week Bill’s Volvo was found parked by the Golden Gate Bridge, his eye patch resting on the dash.

.

The reason why the spokes of the wheels of my toy car appeared to go backward when they were rotating forward is because of a stroboscopic effect created by the pulsating fluorescent light that hung overhead in my grandmother’s kitchen. The phenomenon can be observed in continuous light, though here theories vary.

The reason why protons in the nucleus of an atom do not push apart is because they are bound by the strong nuclear force, which is greater than the positive charge of their electromagnetic force. Or more precisely, neutrons and protons are made of quarks that are bound by the strong force, and it is the residuum of that force that keeps the nucleus together.

I do not know what happened to Bill and never will.

If we only knew—is what everyone says at times like this, but no one knew, no one saw it coming, and that is what is often said as well, and it was. Even after the funeral, when we gathered, when talk was freed, almost nothing was revealed. I had a long talk into the night with the third woman that only ended in more questions and exhaustion. I have also since talked to the family with similar results. And I have tried to contact others over the years but only one email has been returned, the silence lately perhaps because some of them may no longer be with us.

It’s not just that no one knew what happened. Not much precise or substantial was said about Bill himself. I don’t think any of us knew who he was.

I would like to examine a world where his life had not ended so soon, and it wouldn’t matter what kind of world it might have been, or would matter less. But I have to look at the world where it did, and now there is a concern not of helping but of understanding, which might help us in our own lives, and of preserving a memory before it decays. I am left, however, only with contexts and their reasons.

There is his work and the context it might provide. I have searched online databases from the labs and physics organizations and found his name among teams of others in some twenty documents describing proposals for experiments, experiments performed, tests on and refinements to the detecting equipment, a computer program to speed analysis of results, those and whatever thought and time and effort and strain they might represent.

Search for strange baryonium states in p-bard interactions at 8.9 GeV/c

For example, this abstract of an experiment, his largest and longest running, that had that title, published by the American Physical Society posthumously:

A search for SU(3) manifestly exotic Q2Q-bar 2 baryonium states in antiproton-deuterium interactions was carried out at the SLAC 40-in. hybrid bubble-chamber facility. The I = (3/2, S = 1 channel, X-, produced in conjunction with a forward produced neutral antikaon was studied. Such X- states would decay into an antihyperon and a baryon. The fast forward K-bar 0 was detected in a three-view segmented calorimeter placed downstream of the bubble chamber and used as part of the trigger. Upper limits of 0.50–1.63 μb are reported for the X-→Lambda-barnπ-, Sigma-bar -n, Lambda-barpπ-π-, Sigma-bar -pπ-, Sigma-bar /sup +- /nπ/sup minus-or-plus/π- exclusive channels based upon ≤13 events per channel.

The abstract refers to the developing body of the standard theory in which his experiment was designed to find a place. Nature, at its core, is vastly more complex than revolving spheres and their order. There are other particles than electrons and the quarks that make up neutrons and protons, a host of them, many flying free in the universe, most of which can only be observed an instant at high levels of energy before they disappear. It is by studying those that physicists hope to understand the universe of all particles and the nature of all forces. The language is impenetrable to anyone who does not know the physics and the words are odd because there are no common words to signify what is not part of our common experience. The term quark was lifted from James Joyce. Physicists, like writers, have to appropriate their words or make them up. Strangeness, though, is not some ambiguous term that hints at mystery and uncertainty but rather refers to a property of particles that has precise meaning and can be stated in a formula that describes their decay in strong and electromagnetic forces.

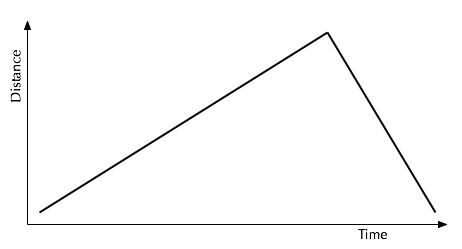

The only thing I understand from the abstract is that the experiment produced no meaningful results. It only had two citations online, an indication of its influence in the physics community and its contribution to the theory. His other, earlier, experiments had few as well. But science depends as much on failure as success. A failed experiment points to reformulation and another try. Yet a particle physicist only gets so many chances. Bill could only advance in his research by performing experiments, but there were just a handful of accelerators in the world powerful enough and only three in the US. Getting the time needed on them depended on having success and building a reputation, but time was expensive and scarce, and he had to compete with others. A team had to be assembled who might impress. Scientific committees had to be convinced, as well as the US government, specifically the Department of Energy, who provided most of the funding and for whom his work had no practical value, adding the difficulty of all the maneuvering and sidetracks involved in convincing committees and government agencies. Bill talked about another experiment he performed that he thought was not worth running—he said the reasons for its being accepted were political—but he had to take what opportunities presented themselves, and there were few. We see this situation elsewhere, in other pursuits.

Add to those difficulties the demands of the science itself, so involved, so complex, so abstruse, particle physics still hovering over the borders of the unknown, along with the pressure of always having to be exactly right. Factor in the ambition, the desire for final comprehension, total grasp. It is possible for physicists to get stuck in the wrong theory. Some hit the ceiling of their abilities and can’t make the leap to the next level of a theory. But it is possible Bill never had a chance to find out what he could do. Practicing particle physics can leave a physicist stranded.

Then there are the effects of channeling oneself into abstract thought, which might exclude other ways of thinking, and multiply those by the strain of staying there for years. It is a place where it is easy to put too much importance on some details, or not know what others are worth, or let a few slip, where one can get caught in loops.

But I am just guessing and speculate only on possible tensions, not the desire that might have sustained him, nor the parts of him not involved in science. Some of the challenges, instead of taxing, might have driven him and given him a place where he thrived.

No one saw mood swings, though there was talk of withdrawal. But we all pushed ourselves and withdrew from time to time. I did have reservations about what was said by some I met and what wasn’t, about what they knew, how broad, how human their understanding, and not just the scientists. We all had committed ourselves to fields that channeled thought and limited understanding, not that we were self-absorbed but that our selves could become absorbed in what we were doing. And we all had hit ceilings, or were aware of them and knew we might be approaching.

The funeral was a brief, quiet session, a diffident motion towards uplift and comprehension, yet still it brought revelation, but not insight into Bill, but what I saw in us, in our quiet, drawn faces. What was opened up is the impression of Berkeley that still shadows my other impressions, what I had not seen before or was fending off. There would be days when our energy dissipated toward nothing, when we didn’t know ourselves, leaving us separate and alone in broken silence.

Not just Berkeley, but what I began to see after, or had put off seeing, elsewhere, everywhere, and still see no matter how we think or what is thought—how distant, how disconnected we all are, how little we understand.

When his apartment was cleaned out, the only thing discovered out of the ordinary was a file he kept on the UC Davis campus police, who he apparently thought were keeping an eye on him. Likely, in his head, there were other spies.

.

What a piece of work is a man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties, in form and moving how express and admirable, in action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god: the beauty of the world, the paragon of animals. . . .

They are the words of a man whose connections with the world have been severed, who questions the value of his existence and debates keeping it, a man who talks to himself, and to ghosts.

Perhaps it is his noble father Hamlet has in mind, as well as himself, or what he might have become had it not been for the murder that ripped apart the fabric of Elsinore, where now there is no beauty and nothing is apprehended well. His words create a model to set against his corrupt stepfather and corrupted mother, and against the others, including Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, sent by his parents as spies and to whom he speaks those words, his suspicions aroused.

Yet his words only create a picture of perfection, impossible in its reach and wholly abstract in conception, a container that does not contain anything. The picture could be the obsessive projection of a man who has become disturbed, one that invites a comparison against which no one will stand up well, not even a noble prince. He has already began to slide, just before, in his talk with Ophelia, where his feigning of madness gets out of hand.

Whatever the case, Hamlet’s options are narrowing to a single exit and there is almost no one he can trust.

There is this context and its reasons, and I have no other to examine. The Earl of Oxford, those books Bill had on his shelf—how could anyone question the identity of the author whose writing has set the standard against which all of literature is measured, unless he identified with one he believed was misunderstood, unvalued and unknown, an interest that could only have grown as his frustrations mounted and fed suspicion as he narrowed his gaze to pictures of subatomic events to find their perfect order, his world shrinking to a nutshell. That interpretation fits the facts and has the most compelling logic, or the most compelling logic we know.

But I have read the books Bill showed me and others more recent and am convinced Oxford wrote the plays. The evidence is large. The plays are filled with correspondence to his life and knowledge. I have more reason to accept his authorship than much else I believe, including the nature of our universe, the existence of quarks, the play of forces. If knowing an author matters, even if Oxford didn’t write the plays he provides a fuller study than the man from Stratford, about whom we know almost nothing. Reading those books has made me wonder about other certainties to which our sanity clings.

Oxford’s family ties to the court went back centuries, but, while intimate with the queen and her entourage, he was alienated from that life and had little room to move. Praised as the man whose countenance shakes a spear, he took that pseudonym because the code of nobility forbade peers staging plays or publishing them under their own names. Nor could the court, unsettled and conflicted, allow the common public to know one of its own was revealing its inner tensions, reflected in his plays. Oxford’s pursuit, writing, like particle physics, like other ambitions, contended with contingencies and risks.

Hamlet especially reads like autobiography both in overall conception and in its details. Oxford’s father had an untimely death, and, like Hamlet, Oxford lost much of his birthright through questionable maneuvers. He had to contend with his meddlesome father-in-law, Lord Burghley, the source for Polonius, and with Burghley’s spies. He was captured and ransomed by pirates; his brother-in-law was sent on a mission by the queen to Elsinore, where he met courtiers with the names Rosenkrantz and Guldenstern.

I don’t know where Oxford takes me, though. Like the passionate and aspiring Hamlet, he could only brood on what might have been, and, like Hamlet, he stumbled in several places. He may have lost himself in writing the play, at least a moment, but also an eternity.

Bill, Oxford—differences aside, I am left with the essential common term: Hamlet. And there’s the rub. The problem with thinking about Hamlet, and wondering who created him and why, and wondering why someone should have wondered who his creator was, and thinking about someone who might have been like Hamlet, is that you become Hamlet yourself, doubting everything and not knowing where to stop.

Maybe the Elizabethan picture of order itself is an obsessive projection of the times, against which Oxford, like Hamlet, strains. Or maybe it is the order they both embrace. Either way, putting us at the center, metaphorically, can be a kind of madness. The play itself asserts and at the same time questions identity in almost every line, while its repressed plot and swelling individuality push against the seams of structure, against any kind of order.

And perhaps physics itself is an obsessive compulsion to grasp, a breeding ground for neurotics.

But such an analysis, however tempting, however compelling, is closed off itself and can lead to more obsession. A picture of madness is only a picture of madness, from which there is no escape. The only thing I am certain of is that if you look for madness you will always find it.

This too I saw in Berkeley, where we learned to doubt and were doubted at every turn, where people talked to themselves or bottled up. There were days when our minds would flare, separately and together, on the streets, in the cafés, in the classrooms, in our gatherings at our apartments, when the air was filled with suspicion, leading to injury or injuries contemplated, to random disruptions, Hamlets all of us pulling or sheathing swords.

And saw elsewhere later.

And everywhere.

The world is filled with spies.

Hamlet, of course, was right about the ghost and much else.

Oxford remains a ghost.

I do not know what else Bill was right about or where it left him in a life where occasions might have informed against him.

I—no one—knew him to be anything but kind and honest.

He must have been in pain.

I will never know who he was.

No letter.

.

It is late, and I have been up staring at a screen where I see these words:

There has been no one else in my life like Bill, little as he was in it. Slender and soft spoken, not withdrawn but not forthcoming, had he found himself in a crowded room. . . .

When I look away to rest my eyes, I see only night black against the window, the glare of a desk lamp, and my glassy reflection, looking back. On my face, lines of weariness and anxiety I didn’t know were there.

We are well, all is well, all is as it should be.

Everything I once thought solid has melted into air.

I grew up looking at pictures of order that located and reassured. Really, they did not explain anything but rather closed off questions and explanations. There are advantages here, however, and at times I miss them. Equality itself was only a bare concept that told us nothing about ourselves, but at least it provided a vanishing point in a perspective that slowed us down, gave pause, and allowed some changes.

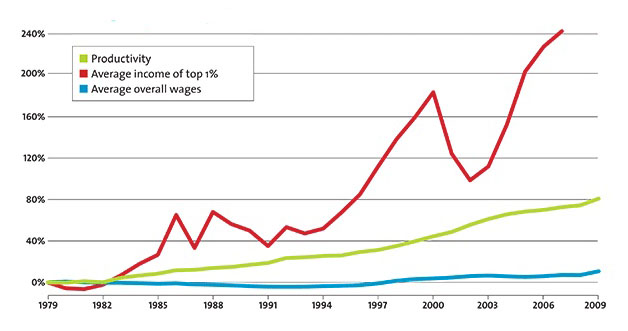

Now I look at pictures not of buildings and people moving among them, but of long rooms where men and women sit at long tables and make decisions, and of larger rooms divided into boxes, where more sit and work, though it isn’t clear what any of these people do. And I see pictures of performance and aptitude in lines on graphs that are supposed to rise, and of shifting bars of attitudes and desires, though it isn’t shown where the lines should end or the bars settle. I also see pictures of an outside world where there are pretty trees and pretty skies and people moving in a soft ether, not quite smiling, and at the bottom pastel pills to ease depression, along with words of warning.

I do not know why this world exists.

Our metaphors have slipped.

A proton is made of two up quark particles and one down; a neutron is made of three quarks as well, two down, one up. In both protons and neutrons the quarks are bound by the interaction of gluons between them, particles that carry the strong force, just as photons carry electromagnetic interactions, such as light. Some of that force escapes the binding of quarks into neutrons and protons, and through more particle transformations binds neutrons and protons together to form nuclei. All this interaction occurs in an atom’s infinitesimal heart.

Particles of what? Gluons, like quarks, like all particles, are only bundles of energy with various properties, in various states and motions, or that is all we can know about them. There is nothing to pick up and throw against a wall or hold before your eyes. The process of binding cannot be pictured but only explained by complex formulas that analyze fields, by making calculations and observing how it works. And the process is still more complicated, and much is still debated, still not understood. Gluons may yet be replaced by something else. Yet experiments continue to return consistent results and point to fundamental order. Other evidence is unassailable: the energy from the interactions that bind a nucleus, when released, can be used in nuclear reactors and bombs.

It must be exhilarating to come this close to nature and feel its pulse. It is exhilarating to think about those who have looked and what they have discovered, the complexity and power in the smallest things, their order. And it is exhilarating not to rest with commonplace appearances of anything, not let them pass, but inspect them closely and think about their order. These thoughts, those efforts, their possibilities, charge the part of us that stirs us. It is exhilarating simply not to stand still.

. . . in apprehension how like a god: the beauty of the world, the paragon of animals; and yet to me, what is this quintessence of dust?

Perhaps Hamlet is giving in to his mood, or perhaps he is losing his grip, but quintessence is a term used by the Greeks, the fifth of the five elements, the eternal stuff of the heavens, the spark that inhabits the smallest part, yet from which Hamlet has been divorced by circumstances and whatever else, further in and further out.

The black picture from the bubble chamber I saw in Bill’s office, however, did not show tiny people walking its white lines carrying pieces of paper or sitting at long tables, much less golden men and women on thrones or fantastic animals or winged spirits or tailed demons, not malevolent stirrings or glowing benedictions, not even a mysterious tremor of an unvoiced sign that indicates one thing could or should be another. The order of the world has nothing to do with the order of our world. It has always been that way. Physics just brought the point home. And if we think about it, we realize the order of our world has never been that orderly or good. It is exhilarating, too, and anything else we might want to feel, and we can feel anything we want, to think about all the things we do not see in the black and white picture and what not seeing them might mean.

Ashes to ashes—there are other ways to look at dust.

There was a condition, not named, not diagnosed, not treated, whose cause could have been internal, chemical and/or psychological, or it could have been environmental, or a combination of all those causes. Most likely there was a nexus of causes, accidental to us but which followed a nexus of orders whose complexity cannot be sorted out, though I do not know what sorting them out might explain. There is no name, however, for the condition that makes one wonder and reach. We only have names for conditions when life goes wrong. Nor do I know if the first condition might not be related to the other, whether the two can be separated. I only know it is impossible to think of Bill’s life without the second. I doubt it is anything he would have wanted to consider or could even have imagined.

There is an order to the world and we have a good grip on its process. Ultimately everything at its root is the result of the interactions of particles. It is possible to theorize the process extending to consciousness itself. Yet the complexity from quark to the simplest molecule is vast. The complexity to extend the process out to a mind, to thought, is unthinkable. It would take—and my guess is as good as any—a computer larger than the size of all of our imaginations an eternity to make the calculations. But also such a study would reduce awareness to the terms of the process, self-referring.

In the beginning—

The ultimate goal for particle physicists is to discover the single force that unifies all forces, which, they theorize, was the force that existed at the very beginning of time before it split into the other forces. Yet most concede they will never have test equipment anywhere close to being powerful enough to perform an experiment to find it. There will always be a ceiling.

I did not reject the pictures of order I saw growing up because I did not believe in order but because they did not hold the order in which I wanted to believe. I have not stopped wanting to believe, though I am less sure why. I want to feel I have a place where I can move among others and be moved alone, where there is a picture of understanding that explains this motion. And I still want to believe that pictures of the order of our world are not made up, that there is connection between them with what I see when I look out, even though I know none exists.

We only know the orders of processes that only know themselves and infinite complexity, further in and further out, infinitely beyond our reach, those and our metaphors, and whatever terms we can manage to stick between the terms of tautologies, whatever ambiguities we can suspend.

I have read Hamlet at least a dozen times over the years and still reread it. Every time it is a different play. I do not know what it means. When I reach the final scene I feel a dozen different ways. Sometimes I feel charged, with varying qualifications of thought and mood, because order has been reaffirmed. Its collapse shows its force, the possibilities that remain had it not been corrupted. Sometimes I only see senseless death littered on the stage. A prop has been pulled out that supported nothing. Sometimes I don’t know what I feel but am left with complex moods split in intricate ways, none of them coherent.

Every time I leave the play I am a different person.

Every time I return to my world it is a different world, brighter and darker.

The problem with thinking about Hamlet, and thinking about someone who might have been like Hamlet, is that you become Hamlet yourself, lost, not knowing who you are. I have also seen a half-dozen film productions, and I don’t think any actor gets him right, or even that it is possible to stage him. But it is the actors who think they know Hamlet, who fortify themselves with wrongful injury and brace for just revenge, I most question and least understand. Only the Hamlets who reach and doubt and lose themselves seem close to whole.

It is only by projecting our hearts and minds into the world, and whatever else we can think to project, then looking at what is returned that we have a sense of what the world might be worth. But it is only by testing the world, and ourselves, and doubting both, that we have any sense what we might be worth.

Sometimes in the cracks between the words that create the world of Shakespeare’s—Oxford’s?—plays, those ironies, I find release. Sometimes, even if there is no explanation in the words, or the explanations do not explain, at least I find a container and the possibilities of containers that might provide a context for a fall, that hold our doubts and pain and suffering and give them full expression and allow them, allow us, to exist a little longer. Here I see some light.

We should always extend the net of our humanity and not question why it exists.

But I cannot rest without looking at the complexity and power in all things.

And remembering those who once were moved to understand.

While searching the online documents, I did find one sentence I fully understood. It was from a PhD dissertation by a Berkeley physics student with this dedication:

I gratefully acknowledge the friendship, advice, and encouragement of Dr. William Michael, whose enthusiastic interest in all areas of physics will always be an inspiration.

.

.

Gary Garvin, recently expelled from California, now lives in Portland, Oregon, where he writes and reflects on a thirty-year career teaching English. His short stories and essays have appeared in TriQuarterly, Web Conjunctions, Fourth Genre, Numéro Cinq, the minnesota review, New Novel Review, Confrontation, The New Review, The Santa Clara Review, The South Carolina Review, The Berkeley Graduate, and The Crescent Review. He is currently at work on a collection of essays and a novel. His architectural models can be found at Under Construction. A catalog of his writing can be found at Fictions.

.

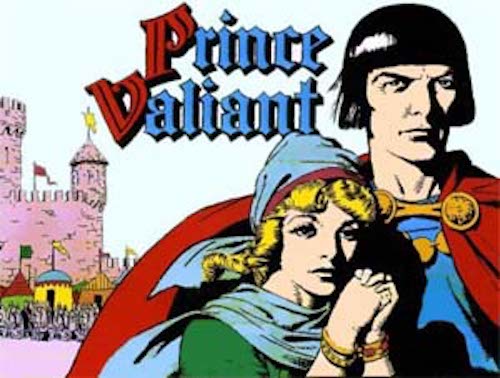

The

The  From the front pages of the novel

From the front pages of the novel

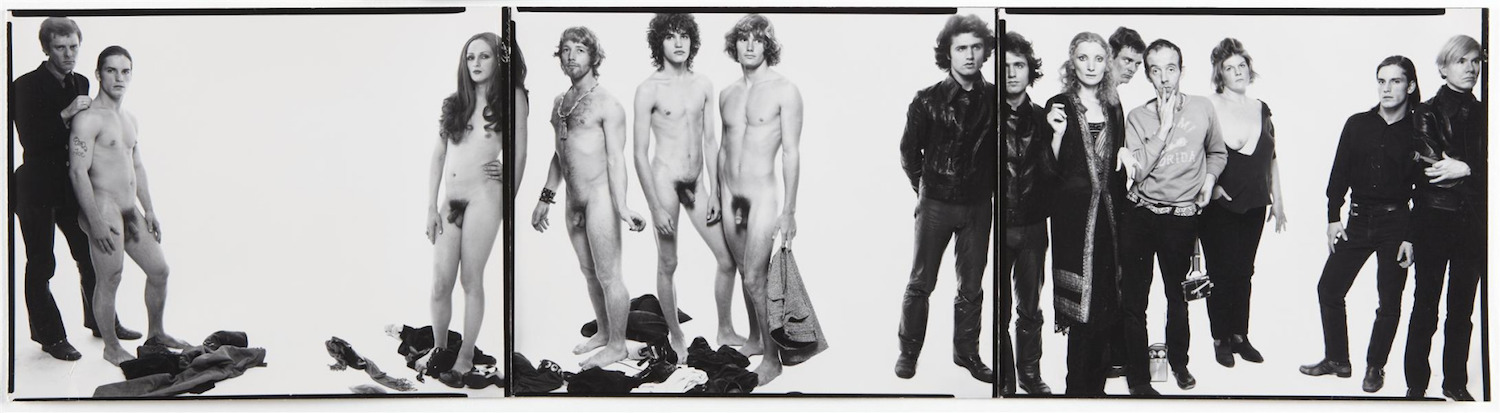

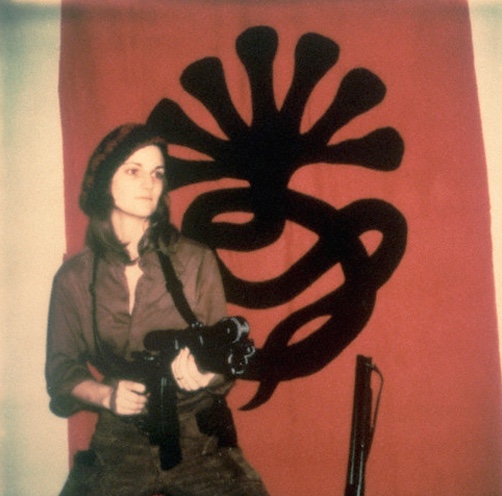

The writer and his double

The writer and his double