I first made Billie Livingston‘s acquaintance last spring when I sat on the jury for the Danuta Gleed Literary Prize. Billie won. This is what the jury said about her story collection Greedy Little Eyes: “In this collection the writer’s eyes are wide open, taking in the world and then reflecting it in all its strangeness and beauty. She pushes edges, teeters on brinks, creating the exhilaration that comes only with taking risks. Her characters are real people in a real world who achieve break-out velocity and recreate themselves by signal acts of courage and self-definition. Frequently, her plots hinge on a demand for justice in a world clouded with calculation and evasion, resulting in a collection as strong in content as it is in style.”

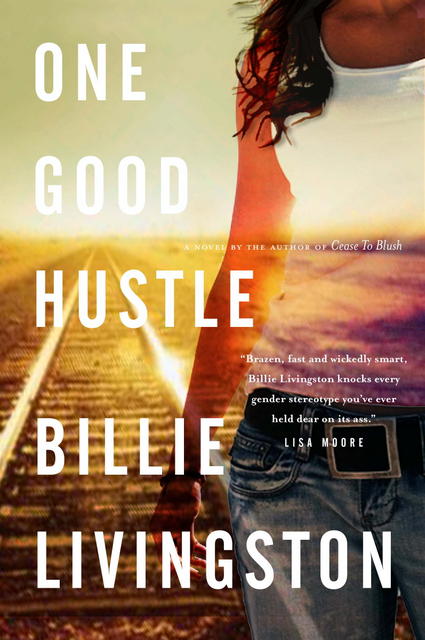

Now, prolific soul that she is, Billie is back with a brash, new novel, One Good Hustle (just published by Random House, Canada), the story of Sammie Bell, a teenage girl with a peculiar problem — her mother is a con artist. Her father was a con artist, too, but he has disappeared, his place taken by yet another con man named Freddy. Sammie lives in a seedy, lost world built on taking advantage of human weakness and greed, definitely not the vaguely glamorous world of that Paul Newman/Robert Redford movie The Sting which somehow managed to make the viewer forget, momentarily, how sleazy, perilous and inefficient the life of a con artist can be. (Isn’t getting a job easier?) Sammie is just beginning to see her mother’s career in the light of a nascent conscience. Her conflict is moral. What we have in the following excerpt is a series of scenes in which the mother drags Sammie to Las Vegas, tapes up her breasts, and makes her pose as an innocent 7th Grader — her mask of innocence meant to reassure the mark. Sammie, in the world but not of it, so to speak, goes along but observes acutely the diminished universe her mother inhabits, her observations signalling the reader that she might just survive her terrible parenting.

dg

§

Fat Freddy is a fence who used to work with Marlene and my dad back when we were a family. After Sam was out of the picture, Fat Freddy weaseled in close to Marlene. I’m not crazy about Freddy. I was happier when he was out of our world, even though she and Freddy used to make pretty good coin together when they ran the Birthday Girl Scam.

It worked like this. Marlene would sit at the bar in a hotel lounge. She’d order herself a drink and ask the bartender his name. Flashing some cash around (“Can you break a hundred?”), she’d say that it was her birthday. Then she’d confide that her boyfriend let her pick out her own present and she’d hold out her arm to show off her new diamond bracelet.

The bartender might say, “Whoa, what’d that run the poor bastard?” She would scrunch up her nose when she whispered, “Six thousand, two hundred, and twenty-five dollars!”

Meanwhile, she’d actually bought it for six bucks off some street vendor.

When she finished her drink, she’d gather up her things and surreptitiously drop the bracelet under the bar stool. A few minutes later, Fat Freddy (it used to be my father) would walk in and take the seat Marlene had just left. Not long after that, Marlene would phone the bar, all frantic. The bartender would look for the bracelet. Freddy would move his foot—“You mean this?”

Freddy wouldn’t hand the bracelet over. He’d just eyeball it and maybe whistle. “Ask if there’s a reward,” he’d say to the bartender.

On the phone, Marlene would cry. I watched her do it, watched her cradle the receiver as she pushed out tears, even though no one could see her. “I have to get that bracelet back.

Please,” she’d beg. “Tell him I’ll give him a thousand dollars. Cash.” Nearly every time, the bartender would hang up and haggle. He’d offer Freddy fifty bucks, imagining he’d pocket the difference when Marlene showed up with the thousand.

Freddy would laugh. “Forget it, man.” He’d pocket the bracelet. “I gotta get goin.’”

The bartender would get anxious then, and Freddy could usually get him to fork over anywhere from two hundred to four hundred bucks. One time, he got five hundred.

Marlene said there was nothing wrong with a hustle like that because if the bartender hadn’t been such a lying, cheating dirtbag in the first place, he’d never have given any money to Freddy. I always wondered about that reasoning, though. What if the bartender wasn’t looking to pocket the difference? What if he was trying to help Marlene, the damsel in distress—save her from having to pay so much to the creepy guy holding her bracelet hostage? How could she know for sure?

But Marlene and Freddy’s business partnership eventually soured. Fat Freddy had a major crush on Marlene. Something happened—I don’t know what, but she made it clear that she wasn’t into him. Freddy couldn’t handle the rejection. He started to become undependable, standing her up when they had work planned. He’d claim she had her dates mixed up, but Freddy was full of shit and Marlene knew it.

Her One-Woman Hotel Hustle was born when she and Freddy were on hiatus.

When I was thirteen, I could still pass for a ten-year-old.

I haven’t got much up top even now but three years ago I was positively infantile. And Marlene had it in her head that she could pass me off as a little girl. Having a little girl, she figured, upped the ante as far as us being needy.

Marlene often drove us over the border into the States.

Sometimes she’d do the little resort towns on the coast or maybe she’d hit Seattle, or Tacoma, or Portland. Now and then, she’d work downtown in Vancouver since, she reasoned, the marks would be from out of town.

If it was a big urban hotel, Marlene would sit in the lounge wearing her Chanel suit—this slim ivory number that managed to look very classy while still showing off her shape. She kept her ankles crossed and out to the side. Some guy once told Marlene that she had well-turned ankles, so she believed they were one of her most excellent features.

She’d have a suitcase beside her chair, a weepy look on her face and a tissue in hand to wipe her eyes.

Usually it went like this: A man would walk by, pause and ask if she was all right. Marlene would nod that she was. Then her face would crumple.

“You want to talk about it? I’m a good listener.”

She’d shake her head but start to bawl her eyes out. The man would almost always sit down and try to get her to talk

about it.

She had come to town with her husband, Marlene would say. “We drove here from Calgary. He was being so strange the last couple of days. I decided to give him some time on his own.”

But, she said, while she was trying on a new dress in a shop, her purse was stolen. Right from under the dressing-room door.

Then she returned to the hotel room only to discover that her husband and all of his belongings were gone. There was a note on the pillow: It was over. He’d fallen in love. To add insult to injury, the other woman was her best friend. Marlene’s husband had not only checked out, he’d left in the rental car.

“How could he do this to me?”

The usual questions: “Have you tried calling your family?”

“Do you have any friends in town?”

Marlene had answers for everything.

“Listen,” she’d say. “Is there any way that you—I could wire you the money as soon as I got home.” She’d drop her head in her hands and sob.

Maybe it was her acting skills, maybe it was the rich-lady Chanel suit, but usually she could get two or three hundred dollars out of these marks.

Except this time. In Marlene’s third hotel lounge of the day, the guy suggested that she might spend some time with him in his room. “How does a hundred sound?”

§

“Do I look a whore?” Marlene bellowed at me later in our living room. She stood with her hands on hips, staring at me. “A piddling hundred-dollar-hooker?”

I was on the couch. “Why don’t you just go back to doing the Birthday Girl?”

“I need a partner for that.”

“Call stupid Freddy, then.”

“I don’t feel like dealing with stupid Freddy’s hard-on every time I want to make a few bucks.”

“Gross! I need to boil my eardrums after that.”

“This is a Chanel suit,” Marlene pointed out. She had bought it a few months earlier from Freddy. Marlene got some screamin’ deals on designer wear from Freddy. “Is there anything about this outfit that says hooker?”

I rolled my eyes. “The guy was a perv. Forget it. God!”

She walked to the window. “Should’ve thrown a horse tranquilizer in his drink and rolled the dumb bastard while he slept.” She turned around and stared at me, her face blank. “Some of the girls who buy from Freddy make a pretty good living that way, you know.”

“Mom.” I shook my head at her. “That’s just skeevy.”

“What’s so skeevy about it? These guys are blowing money on sex, booze, gambling—all kinds of crap. Why shouldn’t they pay me for my time? I’m an interesting conversationalist with interesting opinions. It would be a consulting fee.”

I stared at her. “What the hell happened to you can’t cheat an honest man? Until you give him knockout drugs?”

“You think it’s honest to tell a woman in trouble that you’ll help her out if she puts out?”

I just let that one lay there.

A week later, Marlene asked me if I wanted to go to Las Vegas for the weekend.

“I can’t. Drew invited me on that youth group thing.

Remember? Everyone’s going out on sailboats.”

Her face went sour. “Sailboats? Some Christians. I thought it was easier for a camel to get through the eye of a needle than a rich guy to get into heaven.”

“What the hell are you talking about?”

“Listen, kiddo,” she said. “They’ve got Jesus—I need you.”

Along with boobs and body hair, I was starting to get a bug up my butt about the kind of hustles that worked best when the mark believed he was doing the right thing. Marlene figured this sudden conscience of mine was the direct result of hanging out with those holier-than-thou sons-of-bitches at the church.

And maybe it was. I liked those kids. I liked their lives. So I hardly ever came along any more for the hotel games.

§

In the cab from the airport to Caesars Palace, I looked out the window as the last of the sun hit the crummy old neon signs.

“It’s gross here. They make it look so great on TV.”

“Daylight doesn’t become it,” Marlene said. “It’s an inside town. People come here to gamble.”

“It’s a hole.”

In the hotel room, Marlene opened her suitcase on the bed.

She took out a pale yellow dress that looked as if it were meant for a large toddler. “Ta-da. Your new frock, madam.”

“I’m not wearing that. The hair’s bad enough.”

“What’s wrong with your haircut? It’s adorable. You look like Dorothy Hamill.”

“Great.” I fell back on the bed and stared at the ceiling. “I look like a skating buttercup. I’m fourteen. Why can’t I just be fourteen?”

“Having an innocent child is part of the illusion. There’s nothing innocently childlike about fourteen. Christ, you’re impossible lately. If anyone asks, you’re twelve. Just throw the dress on, make sure it fits.”

Marlene went to the closet, pulled out the ironing board.

I shoved the dress to the side, rolled over and picked around in her open suitcase. There were two little bottles. I pulled one out.

“What’s Ketamine? . . . equivalent to 100mg per ml.”

“Your perfume. There are two little vials in there. I dumped a couple of old perfume samples. We’ll refill them with Ketamine.

I read from the bottle. “Caution: Federal law restricts this drug to use by or on the order of a licensed physician.”

§

Going down in the elevator, I checked myself out in the mirrors. The tensor band she had me wear on my chest was killing. It was supposed to squash my little marbles flat and it was tight as hell. “This dress is brutal.”

“It’s cute.” Marlene straightened the collar. “Christ, I think I can still see boobs,” she whispered, and mashed a hand down over my chest.

“Mom! Knock it off. I’m totally flat. Jill Williams calls me Reese’s Pieces.”

Marlene laughed.

“Yeah. Hilarious.”

“Just round your shoulders a little.”

Marlene led me by the hand through the casino. She sat with me at the nickel slots and ordered Shirley Temples for me. At dinnertime we went to one of the hotel restaurants where the buffet consisted of baron of beef and mountains of crab legs.

My mother ordered the buffet. I thought the buffet smelled like vomit-crusted armpit so she ordered me a cheeseburger.

When our food came, Marlene looked me in the eye, poked a finger into an imaginary dimple in her cheek and said, “Lighten up, misery-guts.”

I crossed my eyes at her. The tensor band itched and I rubbed my ribs on the table edge, trying to scratch underneath.

So she leaned forward and whispered a rude joke about two skeletons doing it on a tin roof. Cracked me up.

“Gross,” I said, coughing on my burger.

Then I remembered this joke that Jill had told at school. Jill and I weren’t really friends in those days but I thought she was funny. “Okay,” I said, “Little Red Riding Hood is walking through the woods when suddenly the Big Bad Wolf jumps out from behind a tree and he goes, ‘Listen, Little Red, I’m going to screw your brains out! So, Little Red reaches into her picnic basket—”

“What do you think of him?” Marlene interrupted. She nodded past me. “The big one.”

I looked over my shoulder at two hefty middle-aged guys. Each of them was eating lobster. The bigger one had a thick beard all greasy with guts and butter. Like a grizzly bear eating a giant cockroach. He took one hand off his lobster to wave.

I glanced back at Marlene, who fluttered her hand at him.

“Why the big one?” I whispered.

“He looks greedy,” she said, smiling past my shoulder.

Three minutes later, the waitress came to our table. She set some kind of cola in front of me and a boozy thing in front of Marlene. “This is called a ‘Beautiful,’” the waitress said. “It’s from the gentleman at that table over there. He’s wondering if you and your daughter are on your own.”

Marlene sighed up at the waitress. “Yes, I guess we are. Oh, maybe you shouldn’t tell him that.” She mouthed thank you over at the grizzly. “Say thank you for your Coke, honey.”

I twisted around and waved, giving him a big phony smile.

Grizzly Adams motioned the waitress back to him.

I continued. “Can I finish my joke now? Okay, so, the wolf goes, Red, I’m going to screw your brains out. Then Little Red reaches into her picnic basket, pulls out a gun and says—”

“Excuse me.” The waitress was back. “The gentleman would like to know if you would be interested in joining him for a cocktail in the main lounge this evening?”

“Well, I don’t know.” My mother’s face turned pink and she covered her mouth. You’ve got to hand it to a chick who can actually blush on cue. I couldn’t help but smile as I bit into my burger.

“Nine o’clock?” the waitress said, and Marlene nodded.

§

Marlene and I were in the main lounge before nine.

Marlene spoke softly. “Once it’s in, I’ll send you to bed and then—”

“Can I go swimming?” I asked out loud. “I brought my bathing suit.” I held up the little pink purse she’d given me to carry.

Marlene looked at it as though it were full of turds. “No.”

“What’s the big deal? Why can’t I go swimming?”

Suddenly Marlene’s sucker was just a few feet away and I kicked her under the table.

“Who wants to go swimming?” the grizzly said.

Marlene jerked her head up and flashed him a cheery face.

“Nobody’s going swimming. It’s almost her bedtime.” She stuck out her hand. “I’m Louise. Thank you so much for buying us dinner. That was awfully generous of you.”

“Hank.” He kissed the back of my mother’s hand and took the seat nearest her. “My pleasure. I made out like a bandit at the craps table today. Made a killing!”

“We all had a good day, then. My little one here won twenty-seven dollars at the slots.”

“Wow!” He gave me a big dopey smile to show how impressed he was. He glanced from Marlene to me. “Look at the two of you. Can’t believe there aren’t a hundred men lined up for your company! Let me order us a beverage.”

Soon the two of them were gabbing about shows in town. Hank said he had tickets to a late show at some other casino. The show was a little on the risqué side but he’d be happy to spring for a sitter for me.

“I can’t stand sitters,” I said. I was being a bit of a jerk but I had decided that that was my character’s attitude for this hustle. Like Sam taught me, it’s good to incorporate your real feelings into your character.

Marlene didn’t appear to agree with me. Keep it light, keep it simple—that’s her motto.

Hank grinned and ordered a second drink.

I took a Rubik’s cube out of my purse and started rotating the squares.

“Come on, honey, put that away and be a young lady,” Marlene said.

I pouted and stuffed it back in my purse.

“She’s okay,” Hank said. “What grade are you in, sweetheart?”

“Seven.”

“Seven? I thought you’d be in grade 8 for sure. Pretty girl. Boy, if I were twenty years younger!”

I looked at his livery lips and bushy beard. “You’re a dirty old man,” I said.

“Honey!” Marlene sounded genuinely irate.

Hank laughed his ass off. “That’s what they tell me. She’s a sharpie, this one.”

I rummaged in my purse and took out the Love’s Baby Soft perfume vial. I pulled the small plastic plug off and sniffed. It smelled sharp. Like chlorine.

Marlene watched me. Her eyes were nervous, but she sighed and said, “Young ladies don’t apply cosmetics at the table, either.”

“It’s perfume, not cosmetics.” I took another whiff.

“Give me that.” My mother took the vial and fumbled with the top.

“I’m going to hit the head,” Hank announced, and got up and left the table.

“I think you might be overdoing it a little,” Marlene whispered once he was out of earshot. She raised her voice and launched into a loud lecture on manners and then, while pushing back the drink glasses, flipped the liquid from the vial into Hank’s rye and Coke. “Here’s the key. Be a good girl and get ready for bed and I’ll be up in a few minutes.”

I found the second vial in my purse. It was supposed to be for our next hotel. I held it so that Marlene could see it anyway.

She shook her head. “We’re not trying to kill him,” she whispered.

I stood as Hank returned. I told him that I was sorry if I’d been rude.

“Rude? Nonsense! We’re pals, aren’t we? You can be yourself around ol’ Hank.” He patted my arm. The size and weight of his hand—like a baseball glove—gave me pause for a second.

I looked at Marlene.

“I’ll be up soon, honey.” She kissed my cheek.

I told Hank good night, and made for the elevators.

Sooner or later, this guy was going to try and move Marlene up to his room. She’d put that whole friggin’ vial of Ketamine in, though—the goof might just pass out in the bar and then what would she do?

As I waited for the elevator, I looked back toward the lounge. The only way for this to work would be for her to actually go with him to his room. Every hustle we’d ever pulled before this was in public.

The elevator opened and I glanced back again just as Marlene was laughing, her head tipped back. Something about the way her mouth opened, as if she could be screaming, made the hair on my arms prickle.

Don’t be a dope, I thought. If anyone can take care of herself, it’s her.

Outside our room, I opened my purse for the room key.

Inside was my swimsuit, just sitting there in a little ball. I had seen the pool when we checked in that morning. The deck had all this gorgeous marble, and white pillars with Roman statues. I wanted to make like I was Cleopatra taking a dip. Once Marlene was finished with this guy, she’d said she wanted to move to another hotel. I’d never get a chance to swim if I played by her rules.

I looked at my watch. I could go down to the pool for half an hour and she’d never know.

§

In the lobby, I ducked out of sight and tried to get a look into the lounge. They were gone, near as I could tell. I slipped behind another column. Man, I loved those crazy Roman statues—they were so friggin’ cool. Marlene and Hank were definitely not in the lounge any more.

I couldn’t wait to step into that warm pool water, the golden lanterns illuminating the deck. I’d be like that chick in the Ban de Soleil commercial. The jingle started up in my head: Ban de Soleil for the San Tropez tan . . .

Standing in the lobby, I tried to recall which way the pool was. Everywhere seemed to lead back to the casino. Signs pointed to the elevators, to the shopping area, to the lounge. I headed back across the lobby toward the front desk to ask directions.

As I came closer, I heard one of the receptionists say, “Security will be right up.”

I stepped up to the desk.

“Disturbance on the twelfth floor,” the receptionist told a man in a black suit on the other side of the counter. “Code two.”

My heart started to bang.

The guy in the black suit spoke into a walkie-talkie. “Security to twelve. Code two.”

I turned and watched two more suited men rush past me to the lobby elevators.

It can’t be her, I thought. She put the whole vial in, didn’t she? He was big, though. Maybe one wasn’t enough. Why didn’t she take the second vial just in case? I looked up at the ceiling as though I could find her that way.

Then I bolted for the elevators.

§

Before the doors opened on the twelfth I could hear the shouting.

I stepped off the elevator and turned toward the noise and there was Marlene on the carpet in the hallway, on all fours, gasping and sobbing. A man and woman were bent over her, trying to help her up, but she would not be touched.

Two men in black suits had Hank pushed face first against the wall, arms twisted behind his back, wrists bent in a way that made them look broken.

Hank howled, his face mashed sideways as he yelled, “It’s that bitch, not me. Kick her ass. Fuckin’ slut-thief!” There was blood on the white door frame beside him.

I scrambled down the hall. “Leave her alone. Don’t touch her!”

Marlene looked up and whispered my name. Blood on her face, she swung her hand, shooing the couple away from her.

“Is this your mother?” the woman asked me. “Sweetheart, maybe you should let us—”

“Fuck off,” I said.

The woman shrunk back against her husband. “Somebody should call the police.”

“No police.” My mother cried it—all her words were cries.

I had hold of her now. Her face. Jesus Christ, her beautiful face. Blood ran down from her eyebrow, and from her nose, and rimmed her teeth. She was all broken. Her hands hung in the air in front of her, blood between her fingers.

The yellow dress puffed around me as I knelt on the floor. This never would have happened if Sam were here, I thought. I have to call Sam.

A few feet away, Hank raged and hollered and I hollered right back. “Shut up, you fat prick.”

I tried to use the hem of my dress to wipe her hands but the synthetic material wasn’t doing the job. “You got any Kleenex?” I asked the woman who still hovered near us.

The woman gave me some tissues and I brought them to Marlene’s nose, trying not to hurt her. “We have to go to the hospital,” I whispered.

“I want to go home,” Marlene whimpered back. “Please.”

“I don’t think there’s a flight tonight.”

“Home. Take me home.”

“Mom. Please. Maybe we should call Daddy.”

“Who? What are you—?” Marlene was panting now. “Take me home.”

§

Security seemed just as happy not to call the cops. Eventually I got Marlene back to our room and packed our bags while she sobbed in the bathroom. I got her some ice wrapped in a towel and talked her into lying down for a while. Then I lay in the second double bed and listened to her cry.

It was 4:58 a.m. when Marlene sat up again. “Let’s go,” she whispered.

I called downstairs and asked to have a taxi waiting.

Lionel Richie and Diana Ross sang “Endless Love” on the radio as we got into the cab. I asked the driver to turn it off, please.

“Leave it,” Marlene said.

The desert sun was just coming up and the radio station gave us more Lionel. Tears ran down Marlene’s face as “Three Times a Lady” filled the taxi. Richie was in town at some big hotel. We passed his name up in lights.

So much dirt and misery and meanness, and here was Lionel Richie droning away about love two shows a night.

We were on the first flight out of Vegas.

§

It was ten-thirty in the morning by the time we got to Vancouver General. Under her sunglasses, Marlene’s face was one big mass of swollen purple bruises and black cuts. She phoned Fat Freddy from a pay phone while we waited in Emergency. She cried. She whispered bits and pieces of what had happened to her.

When a doctor finally saw us, she told him that she’d fallen down the stairs. It was her divorce, she said. The stress was giving her insomnia and the lack of sleep was making her clumsy.

They put five stitches in her eyebrow and taped her nose, gave her prescriptions for Percocet for pain and some Ativan to calm her nerves. Freddy picked us up and drove us back to the apartment.

On the way home, he asked Marlene how much Ketamine she’d used. “A hundred milligrams,” she told him. “One millilitre dumped into his drink. You said—”

“Orally? Ah, honey, no.” He reached for her hand. “Hundred by injection, sure. Orally—that’d barely put a German shepherd to sleep.”

He murmured sympathy and kissed her hand as he drove. I stared at the back of his head.

§

For weeks, Marlene wouldn’t go out. She stared at the TV and popped painkillers and Ativan. She started sipping vodka and milk sometime around noon each day.

When the phone would ring, she barely looked at me. “Tell them I’m not home.” Unless it was Freddy. Suddenly Freddy was the only one who could really understand what had happened to her.

He came by the apartment to see her every couple of days. He brought her a Hummel figurine the first week: a little blonde girl bathing a baby. Marlene touched the smooth, pale arms on the little girl and tears rolled down her face.

Freddy smiled. “Cute, isn’t it? I thought you’d like it.”

“I’m a terrible mother,” Marlene sobbed. She cried full-on for a good ten minutes.

I went into my room and closed the door.

Whenever Freddy made a pest of himself after that, he came bearing designer blouses instead.

It was two weeks after Vegas that I came in from school and Freddy was there, joining her in a drink. This time he had brought her a box of European chocolates.

“Good thing you girls started collecting that welfare cheque a few years back,” he said. “That welfare’s a nice little safety net for a single gal.”

I could feel myself stiffen. “We don’t need welfare. It’s just available, that’s all.”

“Looks like you need it now, sweetheart,” Freddy said. “I think you definitely need it now.” He seemed to leer when he said it.

I wondered whether it was the government cheques or the vulnerability of Marlene’s half-broke face that turned him on.

—-Billie Livingston

——————————-

Billie Livingston published her critically acclaimed first novel, Going Down Swinging, in 2000. Her book of poetry, The Chick at the Back of the Church, was a finalist for the Pat Lowther Award. Her novel, Cease to Blush was a Globe and Mail Best Book as was her story collection, Greedy Little Eyes, which went on to win the Danuta Gleed Literary Award and the CBC’s Bookie Prize. One Good Hustle will was published July 24, 2012