.

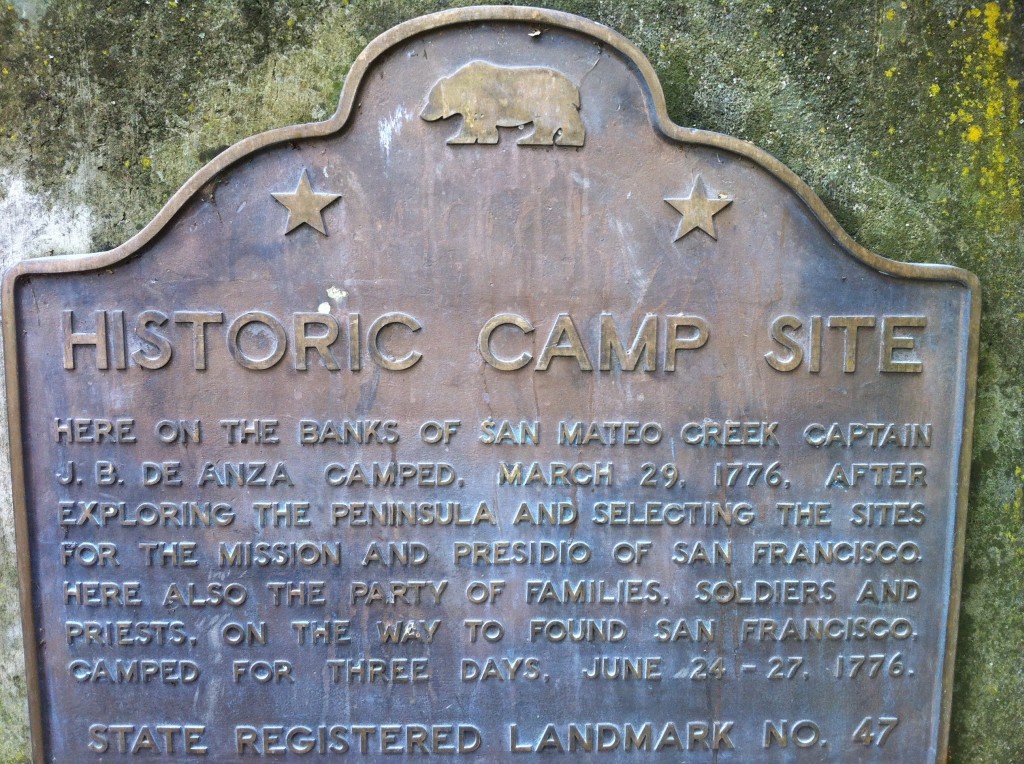

I live halfway between the Road of the Kings and the Avenue of the Fleas in San Mateo, California. Situated on a peninsula seventeen miles south of San Francisco, San Mateo isn’t a young town at all—it was settled by the Spanish long before many other places in America. In 1776 Captain Juan Bautista de Anza came from Spain searching for the inlet to the San Francisco Bay; for nearly 200 years it had remained hidden to European explorers sailing up and down the Pacific coast in summer fog. Anza and his scouting party camped here along a river, naming it San Mateo (after Saint Matthew, the Jewish tax collector-turned-apostle who later spread the word of God in far-flung nations). Anza befriended the native Ohlone Indians living here.

“I found in our camp nearly all the men of the village, very friendly, content, and joyful, putting themselves out to serve us in every way, a circumstance which I have noted in all the natives seen [in California] up to now.” —Captain Juan Bautista de Anza’s Journal, March 29, 1776.

California State Registered Historical Landmark No. 47, DeAnza Camp. Photo Credit: Wendy Voorsanger

California State Registered Historical Landmark No. 47, DeAnza Camp. Photo Credit: Wendy Voorsanger

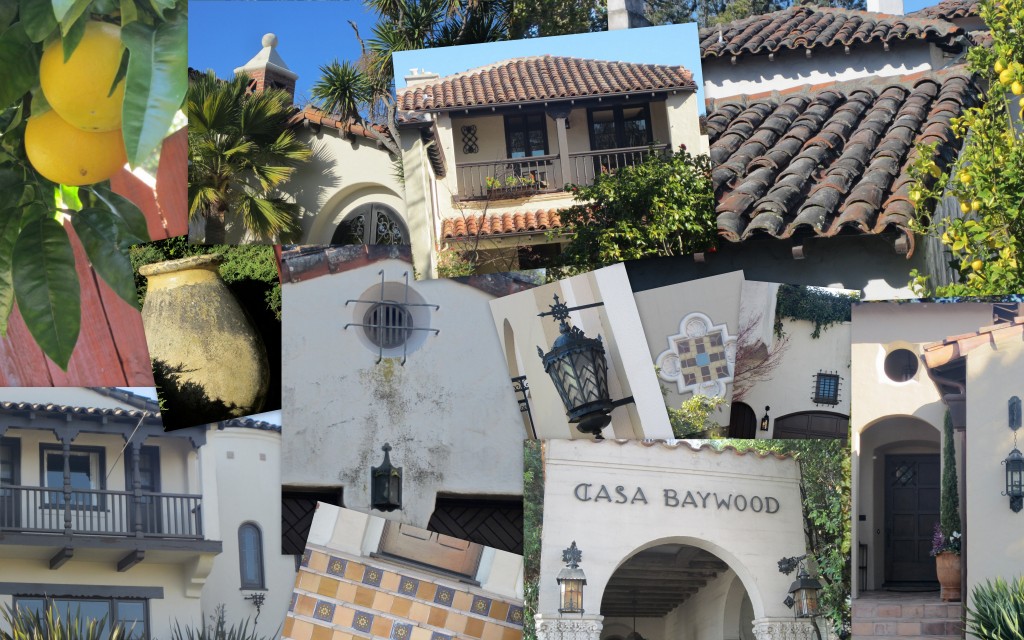

My neighborhood, just two blocks from that original Anza camp, would no longer be recognizable to those early Spanish settlers or Ohlone Indians. What was once a hilly serpentine grassland dappled with stately oak and bay laurel trees, is now organized into wide streets named after Spanish locales (Castillian, Sevilla, Avila, Aragon) and prestigious eastern colleges (Harvard, Cornell, Fordham). The grizzly bear, elk, and pronghorn antelope no longer roam, the wide-open space covered with rows of Spanish and Mexican revival houses. The oaks and their meaty acorns, once prized by the Ohlone, now feed only the black squirrels skittering between the yards. The San Mateo Creek where Anza made camp is no longer wide and flowing with salmon and trout, but slowed and stunted by a large dam three miles upstream. The dam holds back the water from the Crystal Springs Reservoir filled with Yosemite snowmelt delivered via a sophisticated system of pipes originating 176 miles to the east.

Crystal Springs Reservoir at low level. Photo Credit: Wendy Voorsanger

Crystal Springs Reservoir at low level. Photo Credit: Wendy Voorsanger

The front yards in my neighborhood aren’t fussy or fancy but welcoming. Small green lawns are edged symmetrically and blown neat. Plenty of perfectly placed native grasses sit alongside drought-tolerant plants such as yucca palm, flowering sage, rosemary, and fruit trees (lemon, orange, fig) designed to look as casual and natural as California itself.

Spanish and Mexican influences in San Mateo. Photo Credit: Wendy Voorsanger

Spanish and Mexican influences in San Mateo. Photo Credit: Wendy Voorsanger

I find the people here in San Mateo friendly and open, much like Anza found the Ohlone back in 1776. Perhaps it’s because of the mild climate, warm sunshine and blue sky. Or maybe it’s the boundless ocean nearby, 12 miles west over the ridge. Or the delicious evening fog that rolls in at night; nobody has air conditioning—we just open our windows. Whatever the reason, the town exudes a convivial energy. Neighbors smile and wave and take in my trashcan without asking. They put my paper on our porch and ask about my day. I often find myself on the sidewalk long after the sun goes down chatting with neighbors while the kids kick balls in the middle of the street. San Mateo has a trusting sort of warmth that doesn’t require years to earn.

I like to think the Ohlone spirits inhabit us, teach us how to live, appreciate our land and each other. I imagine their bones scattered deep beneath my home. I imagine them wandering the hills in the midnight fog wraithlike, their pacific whisperings coming through my window as a sea breeze as I sleep. But then I also imagine the ghosts of the Spanish buried alongside the Ohlone and figure they have something to say, too. And I wonder how much of our culture is simply a lingering imprint of those who came before.

“Indian Maidens” at the San Mateo post office. Relief sculpture carved in wood by Zygmund Sazevitch, 1935 Treasury Relief Art Project. Photo credit: Wendy Voorsanger

“Indian Maidens” at the San Mateo post office. Relief sculpture carved in wood by Zygmund Sazevitch, 1935 Treasury Relief Art Project. Photo credit: Wendy Voorsanger

To outsiders, San Mateo might seem like an irritatingly superficial, “laid back” place. I’ll admit, I enjoy my superficial pleasantries, not always taking the time to dig beyond surface connections with people. And I do often hang out in nature; our Bay Ridge and Peninsula open space district encompasses over 60,000 acres in 26 wilderness preserves. But most people in San Mateo don’t really fit into that familiar “laid back” Californian caricature. Being relaxed is just an image we carefully cultivated, consciously or subconsciously. In fact, on the contrary, San Mateo is a diverse mix of locals and transplants from around the country (and the world), mixed together into an insanely intense stew of over-achievers and perfectionists.

.

A Reconstitution

I grew up in Sacramento and came to the Bay Area twenty-five years ago looking for opportunity among the numerous Silicon Valley start-ups. I clung to the culture of achievement here because of my deep-seated need to repair the fabric fraying around me growing up amidst the crazy 1970’s California counter-culture of dissolving structures (family and society), mind-altering substances, and latch-key responsibilities. My plan was to do better than my parents, harness all that freedom and possibility, not squander it. Perhaps others came here to escape the confining strictures and suffocating class-based impediments in the places they left. In San Mateo we all seem to be trying to build and rebuild our lives into something more meaningful through intense work, innovation, over-achievement.

Here in San Mateo, it doesn’t matter where you come from. What matters here are your ideas. Your intelligence. Your work ethic. What do you bring to the table? What is your value add? Did you start a company? Launch an IPO? Get your PHD? Fund a mind-blowing technology? Volunteer with an indigenous tribe in a remote location? Invent a life-saving drug? Run a marathon? Start a non-profit? Living in San Mateo offers an extraordinary geographical opportunity for innovation—it’s equidistant between San Francisco and the Silicon Valley. We’re ideally situated to work in any one of the high-tech companies nearby (Google, Facebook, eBay, Twitter, Yelp, Pixar, Yahoo, Genentech, Apple, etc.) or in other industries that serve the technology industry like venture capital and merger and acquisition law.

.

Our Statistics

According to the Bay Area Council Economic Institute, the area has:

- The highest economic productivity in the nation—almost twice the U.S. average

- The most highly educated workforce in the nation, with the highest percentage of residents with graduate and professional degrees

- The nation’s largest concentration of national laboratories, corporate and independent research laboratories, and leading research universities

- The largest number of top-ten ranked graduate programs in business, law, medicine and engineering in the nation

- The highest density of venture capital firms in the world

- The most technology Fortune 500 companies

- The highest internet penetration of any U.S. region

- The highest level of patent generation in the nation, with more patents generated per employee than any other major metropolitan area.

.

Living In a Culture on Steroids

To me, living in San Mateo feels like living in an achievement culture on steroids. There’s a drive for perfection, or a drive to get as close to it as possible. It’s the common denominator among us—this drive for perfection—whether or not we admit it to ourselves. Or to each other.

Our local schools offer parent education lectures entitled: “Inspiring Innovating Thinkers,” “Sports Parenting: Inspiring a Win-Win Attitude,” “Resilience and Optimism in Your Child,” and “The Art of Imperfect Parenting.” Moms and Dads attend these lectures equally. We read books like Making Marriage Meaningful and The Secrets to a Dynamic and Fulfilling Marriage to ensure that we don’t fall short like our parents. We’re trying to become our better selves. We’re striving for perfection, while juggling parenting, marriages, and careers. When we blunder, we call it “a learning opportunity.”

San Mateo is a town catering to people who live healthy; there are six gyms and four yoga studios within a four-block radius from my house offering yoga, the Bar Method, Pilates, Zumba, Interval Cycling and Skinny Jeans classes. There’s also Junior Gym to get the little ones started early. Here in San Mateo, we hike, run, swim, road bike, mountain bike, kite board, paddleboard, and surf. We complete marathons and 48-hour team relays for charity. We drink SuperFood, do seasonal cleanses, cut out carbs, and eat organic goji berries, flax seed, and dried seaweed. Most people I know don’t spend hours on the golf course each weekend talking business over scotch (too old-school exclusive and slow). Instead, after hours networking is done while biking up Crystal Springs Road in tight pelotons on custom bikes wearing coordinated bibs and jerseys; cyclists then track and compare achievements (route, distance, speed, elevation, power, time) using a Strava iPhone APP and celebrating their King of the Mountain (KOM) wins with Racer 5 microbrews.

Craig Chinn and Conrad Voorsanger chat in the neighborhood before a ride. Photo Credit: Wendy Voorsanger

Craig Chinn and Conrad Voorsanger chat in the neighborhood before a ride. Photo Credit: Wendy Voorsanger

Our children are swept up into the achievement culture around them. They play soccer, lacrosse, basketball, and volleyball. They fence, rock climb, dance, swim and dive. They play the trumpet, harp, guitar, and drums. They sing and attend chess club, art class, and robotics clubs. They learn Mandarin, Spanish, and French. They take extra classes outside of school in math and writing at places like Kumon, Sylvan, The Reading Clinic, Academic Springboard and The Tutoring Center. They enter in math competitions, spelling bees, geography bees, and science fairs. They’ve mastered all things computer science and gadget-related, and have moved on to App programming and hacking. We keep them on task with family-coordinated online calendars updated from our Smartphones.

We’re obsessively concerned about the environment, driving hybrid cars and using canvas bags at the grocery store. We walk, ride bikes, and use the carpool lane or public transit (CalTrain or Bart). We conserve water, use compact fluorescent light bulbs; incandescents will be illegal in California by 2013. We recycle and compost nearly everything with a sophisticated stream recycling system. Everyone has three garbage cans: green for compost, blue for all recyclables, black for trash. The black can is seldom full.

.

A Haunting Echo

It feels as if we’re all striving to create a New World utopia in San Mateo, much like the Spanish missionaries did two hundred years ago. Perhaps that’s the long-dead Spanish influencing us from beyond; their zealous drive a haunting echo from the past.

Father Junipero Serra followed Anza, with the hopes of building a perfect utopian society. He and his padres worked fervently (using Ohlone slave labor) to create a network of 21 missions exactly one-day walk apart along El Camino Real (the Road of the Kings). Serra was an exacting and determined perfectionist, much like the people in San Mateo today. But, most people here aren’t looking for Serra’s pietistic existence. We’re on a fast-paced, never-ending quest for a particular type of utopia that takes our constitutional “pursuit of happiness” literally. We’re pursuing that right with intense fervor, all the while portraying the cool substance of a calm demeanor.

Defining Diversity

San Mateo is a multi-cultural and socio-economically diverse town that’s walkable and welcoming. People talk to each other the street. Many languages are heard: Spanish, Russian, Mandarin, Japanese, Hindi. Flower boxes with impatiens dangle from light posts. Public benches with matching iron trashcans are evenly spaced along the sidewalks. Littering is a misdemeanor in San Mateo, punishable by a $1000 fine.

There’s an impressive collection of restaurants: Mexican cantinas, Korean noodle houses, Irish pubs, Italian eateries, and Brazilian Steakhouses. There are countless Sushi and Chinese restaurants, Indian buffets, all-American diners, healthy cafes, coffee stores, and juice bars. Draegers Grocery has organic fruits and vegetables, free-range meat, and sustainable fish. There’s also a Japanese Grocery (Suruki Supermarket) and several Mexican Markets (Market Fiesta Latina, El Azteca Market, and El Faro’s Mexican).

There are more Mexican restaurants in San Mateo than any other; Spanish tapas or native Ohlone fare (acorn bread, deer, mussels, fish) aren’t found anywhere. Perhaps this reflects the Mexican victory of independence from Spain in 1822, when Mexican Generals set about secularizing the California missions and distributing large land grants throughout California.

So what of the Mexican influence in San Mateo? It extends beyond margaritas and enchiladas to the rich Mexican heritage of industrious land labor (cattle ranching, tanning, logging). In addition, historian Robert Glass Cleland said of the Mexican Californians (Californios) in 1833: “They are free from the pressure of economic competition, ignorant of the wretchedness and poverty indigenous to other lands, amply supplied with the means of satisfying their simple wants, devoted to the grand and primary business of the enjoyment of life, they enjoyed a pastoral, almost Arcadian existence.”

Untitled glass tesserae mosaic on exterior Bank of America building in San Mateo; Louis Macouillard, designer and Alfonso Pardiñas mosaicist (Five mosaic panels 25 ft. high, approx. 90’ across).

Untitled glass tesserae mosaic on exterior Bank of America building in San Mateo; Louis Macouillard, designer and Alfonso Pardiñas mosaicist (Five mosaic panels 25 ft. high, approx. 90’ across).

The Mexican culture also introduced liberalized divorce, custody, and property laws for women in California long before the rest of America recognized gender equality. In fact, in 1844 one of the largest ranchos on the Peninsula (4400 acres) was run by a Mexican woman named Juana Briones. Juana fled her drunken husband in San Francisco with her eight children to buy her own ranch on the Peninsula, where she began raising cattle and farming. Historical accounts say she prospered, acquiring five other ranches over her lifetime and living a fulfilled existence with her large family around her.

As a native Californian, I can’t help but see Juana as some sort of standard-bearer I should emulate. After all, she seemed to find opportunity and achieve happiness, all while juggling the pressures of a demanding career and raising children. Living in San Mateo, I feel as if Juana’s endowment fills me like a deep, resonant well of possibility. Perhaps her lasting legacy is stored inside me, simply because I live here.

.

At the Center

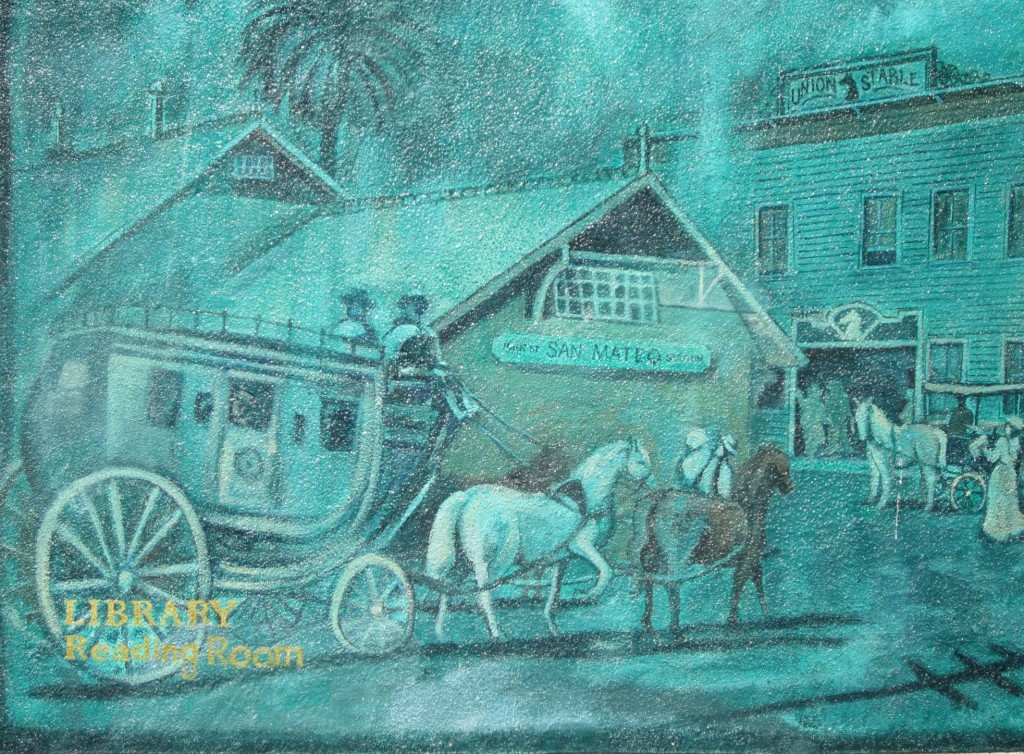

America took control of California upon winning the Mexican-American war in 1847 and broke up (“redistributing”) the large Mexican ranches. This slice of history is seen in Central Park, 16-acres bordering the north part of San Mateo. The oaks and bay trees have stood here since the Ohlone, but the pine, cedar, redwood, and fig trees were planted for the estate of Charles. B. Polhemus, director of the San Francisco-San Jose Railroad. Polhemus grabbed the land from the Mexicans, and built a grand estate where Central Park now sits, with a 13-room Victorian mansion and lush landscaping. He later sold the estate to a sea captain named William Kohl, who then passed the property on to the city of San Mateo in 1922. The mansion was torn down long ago, replaced by a large circular grassy area in the center of the park. It’s a vibrant public space where the whole town congregates: parents bring small children to romp in the playground and ride the miniature train for a dollar, older kids around on bicycles and skateboards, seniors practice Tai Chi under the shade of a pine tree. A drummer sits on a bench thumping out a mesmerizing, visceral beat. There are also a baseball field, tennis courts, a community center, rose garden, and formal Japanese tea garden with a granite pagoda, koi pond and bamboo grove.

“Library Lane” mural depicting American expansion in San Mateo, by muralist, Norine Nicolson, 1989.

“Library Lane” mural depicting American expansion in San Mateo, by muralist, Norine Nicolson, 1989.

The black squirrels live here in Central Park too, fed by older folks who come for daily walks with nuts stuffed in their pockets. There are no more quail or great horned owls as in the days of the Ohlone. They’ve diminished in numbers and headed up to the ridge with the falcons and condors, but there are still plenty of finches, doves, warblers, and jays to liven up the park with song. Lining the park are several senior apartments, upscale and subsidized side by side.

Two blocks east of the park—across the train tracks—men eager for work gather on street corners hoping for day labor. No one asks for documentation. Sometimes the men congregate in the parking lot of the Worker’s Resource Center where a County Mobile Health Van offers free health assistance.

.

The Strong Current of History

Sometimes living amidst all this sunshine and happiness can be difficult, the pressure and pace crushing, the competition daunting. Opportunity isn’t ubiquitous, and luck is often elusive. Amongst the intense rush, the quiet contemplation and reflection that our forebears enjoyed is often fleeting. When I catch a slow moment, not originating from evaluation and measurement or leading toward any admirable achievement and success, I think of those who came before and how deeply they influence what it’s like living here. Walking along San Mateo Creek, I think of the Ohlone catching fish. Sitting on the patio listening to my son playing a malaguena on his guitar, I think of the Spaniards. Watching a hummingbird from my window suck on lemon blossoms, I think of the Mexicans who brought those trees here. I delight in these simple moments, circling around like an eddy in a river, slowing me into a reflection of swirls and ripples and the glassy texture of the water itself. Then the strong history of my town grabs hold and pulls me along once again, throwing me like a pebble into the single fast moving cultural current that is San Mateo.

— Wendy Voorsanger

.

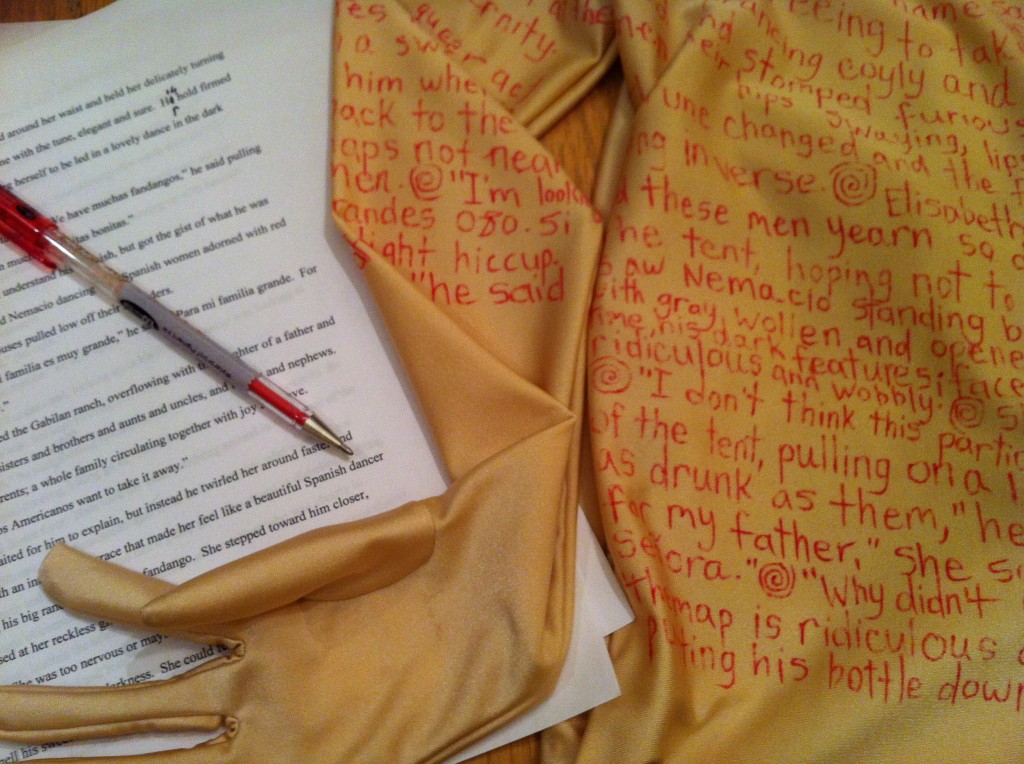

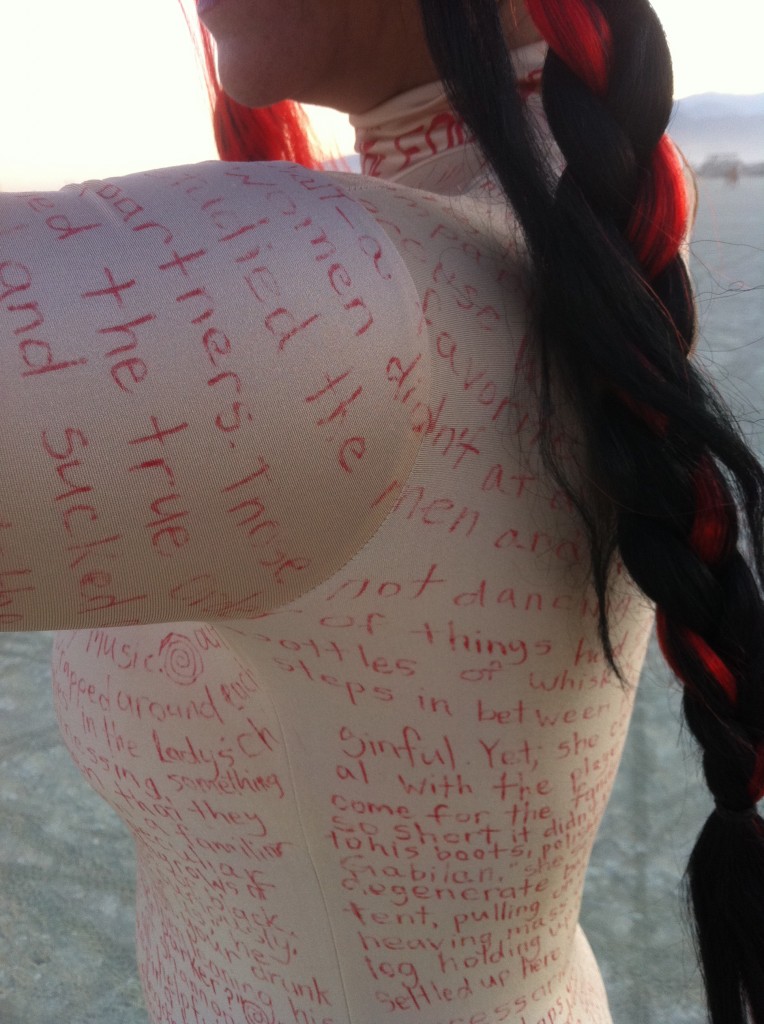

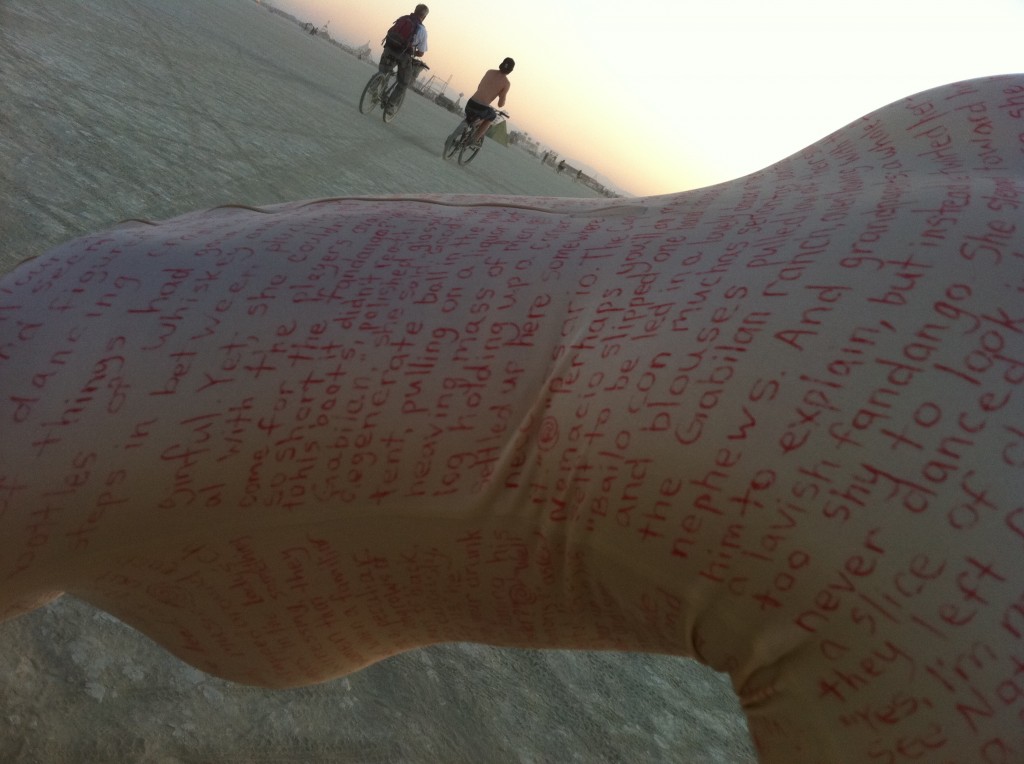

Wendy Voorsanger is a graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts. She is a shadow contributor to NC, writing on the arts and creating art (see her gorgeous Burning Man novel skin) without actually appearing on the masthead. She lives in San Mateo with her husband and children and is at work on a historical novel about California.

See also our growing list of What It’s Like Living Here essays, a staple of the NC economy.

.

.

“Trip to Paradise,” poem painting by Tonia Colleen, current VCFA fiction writing student (Watercolor on rice paper, with the poem hand written in ink. Some of the images are from the artist’s original wood carvings.)

“Trip to Paradise,” poem painting by Tonia Colleen, current VCFA fiction writing student (Watercolor on rice paper, with the poem hand written in ink. Some of the images are from the artist’s original wood carvings.)