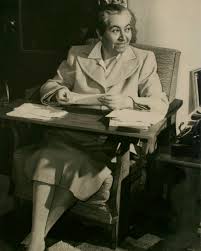

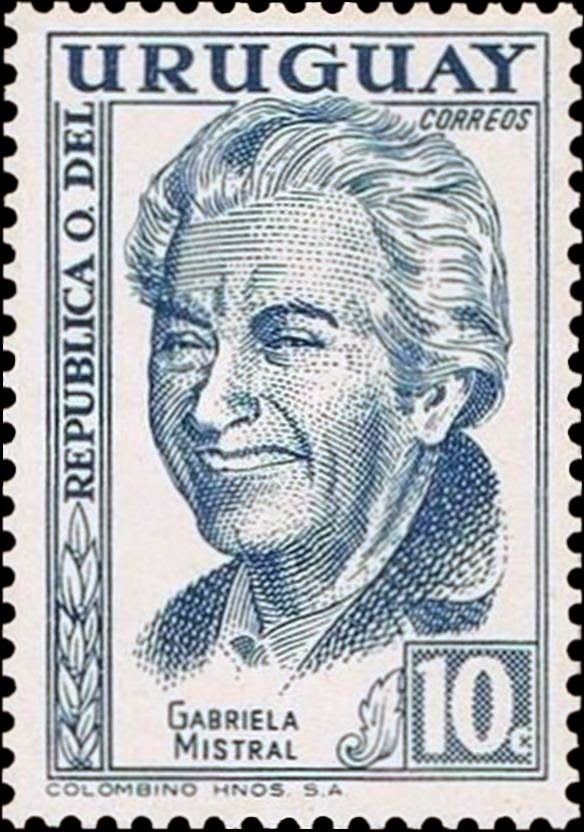

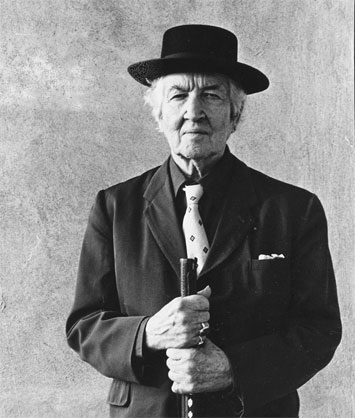

It’s probably unfair – at the very least it’s risky – to place an old photo of the poet Marie Ponsot, surrounded by five of her seven children, at the beginning of this review of her work. The implication is that the state of motherhood defines and constrains a poet qualitatively, and I don’t think that’s true. But the photo certainly suggests something quantitative about Ponsot’s creative output for a certain period of her life, and explains the slow development (by anyone’s standards) of her career – a first book, True Minds, championed and published in 1956 by Lawrence Ferlinghetti for his City Lights series, and a second book (Admit Impediment) in 1981. If you’re doing the math, that’s twenty-five years between first and second books. During those years, she divorced her husband, the French artist Claude Ponsot, and raised the children as a single parent. To support the family, she taught basic composition at Queens College and took on translation work, translating over 30 books from French into English. Those translations include celebrated versions of La Fontaine’s fables and Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy tales.

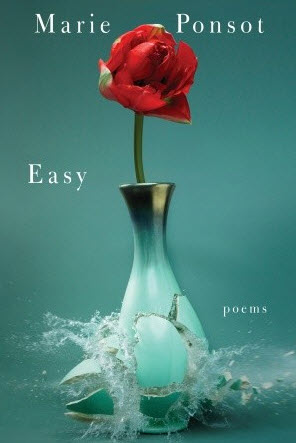

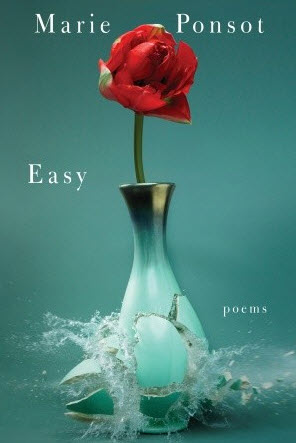

Since that second book of poems in 1981 – thirty-two years ago – there have been only four more books from Ponsot – The Green Dark (1988), The Bird Catcher (1998), Easy (2009) and one collection from the previous volumes – Springing: New and Selected Poems (2002) which also has a scattering of new poems. Easy was published just after Ponsot turned eighty-eight.

Whatever it is, it’s not as “easy” as it seems….

Whatever it is, it’s not as “easy” as it seems….

I offer up the photo of Ponsot with her children in the lead position as a visual explanation of her atypical career trajectory. The adjective “undersung” attached to her name might be explained by the hyphenated adjective at the beginning of the biographical notes in Contemporary Authors Online: “In the course of her career, Ponsot has published several widely-spaced collections of her work…” [emphasis is mine]. Spacing, it appears, can be everything.

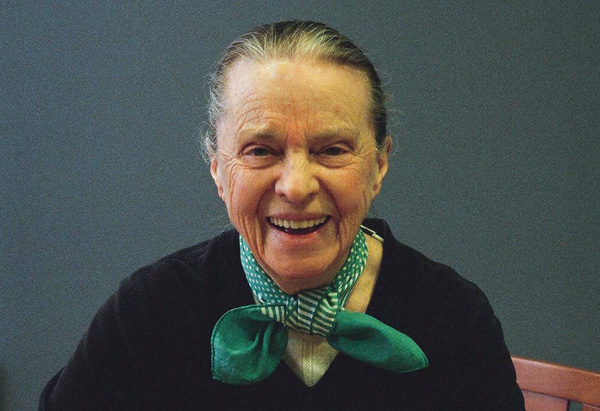

Five children gathered around their mother, and all appear to be under seven or eight years old. When I look at this photo (and I have looked at it plenty – I kept a copy of it taped up on the file cabinet near my computer for a few years) I think of Robert McCloskey’s Caldecott-award-winning picture book Make Way for Ducklings, especially everyone’s favorite page in that book, the one showing all the ducklings walking in a row: “One day, the ducklings hatched out. First came Jack, then Kack, and then Lack, then Mack and Nack and Ouack and Pack and Quack.”

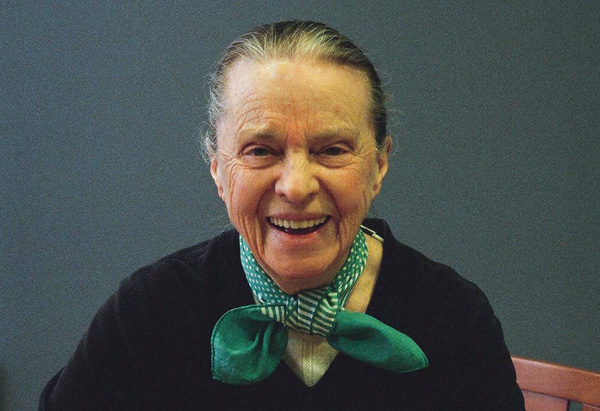

It’s a charming drawing, and I see a lot of charm in this photo of Ponsot with her children. There the kids are, though not widely spaced; there is the poet with her beatific smile. Or maybe I’m projecting my own comfort level with odd career trajectories onto Ms. Ponsot. Is the smile beatific? When I showed the photo to a few other people, their descriptions ranged from “addled” to “deer in headlights” to “amphetamines.” So maybe we see what we want to see.

But after reading through interviews of Ponsot and studying her poems, and after meeting her myself a dozen years ago, my theory is this: The woman – who will turn 93 in May – has a preternatural ability to enjoy herself, no matter what the task. The word “preternatural” fits; Webster’s definition says it describes something “suspended between the mundane and the miraculous.” That fits Ponsot to a T. In a piece for the PBS Newshour in 2009, she said, “I write for pleasure. I am a firm supporter of the pleasure principle of life. I think things that we really long to do – and are refreshed by doing – are what we ought to spend a lot of time on. Why not?”

The Spirit of “Why Not?”

The Spirit of “Why Not?”

Of course, Ponsot’s desire to write must have come into conflict with other interests – including motherhood – from time to time. Few of us are single-minded and focused enough not to feel conflicted about competing desires, and conflict like that can make a lot of internal (and sometimes external) noise. Unfulfilled expectations and thwarted desires can be disruptive or, in the case of someone like Sylvia Plath, destructive. Ponsot’s attitude is more accommodating. Consider this poem, written after her divorce:

AMONG WOMEN

What women wander?

Not many. All. A few.

Most would, now & then,

& no wonder.

Some, and I am one,

Wander sitting still.

My small grandmother

Bought from every peddler

Less for the ribbons and lace

Than for their scent

Of sleep where you will,

Walk out when you want, choose

Your bread and your company.

She warned me, “Have nothing to lose.”

She looked fragile but had

High blood, runner’s ankles,

Could endure, endure.

She loved her rooted garden, her

Grand children, her once

Wild once young man.

Women wander

As best they can.

The grandmother in the poem envies the beggar’s freedom to “sleep where you will / walk out when you want.” The speaker of the poem wonders and wanders while “sitting still.”

When I met Marie Ponsot– she was already eighty years old – she didn’t seem capable of sitting still. She had been invited to read on campus at the University of Washington by the Counterbalance Arts organization, and I had been asked to introduce her. She met me for lunch already having spent the morning busy with a visit to the Seattle Art Museum, and I expected her to be worn out, in need of a rest. Instead, she was energetic, animated, and fully engaged in our conversation. She described having seen, at the museum that morning, a glass bowl three-thousand years old, and she commented more than once on how remarkable it was that anything so fragile could have survived so long without breaking. As she talked, her passion and enthusiasm about this small object left me wondering whether I could keep up with her for the rest of the afternoon, though I was thirty years her junior. That’s not to say she was giddy or over-effusive. But her high energy level at the time was clear; that same energy beams out from this photo and the poem which follows it.

ONE IS ONE

Heart, you bully, you punk, I’m wrecked, I’m shocked

stiff. You? you still try to rule the world — though

I’ve got you: identified, starving, locked

in a cage you will not leave alive, no

matter how you hate it, pound its walls,

& thrill its corridors with messages.

Brute. Spy. I trusted you. Now you reel & brawl

in your cell but I’m deaf to your rages,

your greed to go solo, your eloquent

threats of worse things you (knowing me) could do.

You scare me, bragging you’re a double agent

since jailers are prisoners’ prisoners too.

Think! Reform! Make us one. Join the rest of us,

and joy may come, and make its test of us.

It’s not everyone who can write energetic sonnets that threaten and yell back at their own metaphorical hearts. Nor can many poets surprise us with rhyme as well as Ponsot. It’s the rhymed couplet at the end of this poem which rings like a bell and announces the fact that the poem is an Elizabethan sonnet. Once that happens, the reader returns to the opening of the poem to find the rhymes unfold in their traditional order, ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG. Ponsot disguises the rhymes on first reading by offering us choppy mid-line sentence endings (“Brute. Spy. I trusted you. Now…”) and by highly enjambed lines (“I’m shocked / stiff”) as well as non-traditional stanza breaks (6 lines/5 lines/ 3 lines.) The rhymes are subsumed until the end. But, going back and looking down the end words of each line, there they are, plain as day.

Beginning poets often go wrong with the tonal register of a modern sonnet, believing that the formal elements go hand in hand with heightened diction, when what the successful modern sonnet needs is a more conversational tone (“…you punk…”) to help readers relax. Even the ampersand, rather than the word “and,” helps the sonnet feel more comfortably modern.

Ponsot manages to find a conversational tone for many of her formal poems, without the work suffering from what the critic Suzanne Keen calls “the strain of artfulness.” Take these ars poetica lines:

COMETING

I like to drink my language in

straight up. No ice, no twist, no spin

—no fruity phrases, just unspun

words trued right toward a nice

idea, for chaser. True’s a risk.

Take it. Do true for fun.

As many critics have pointed out, the poem is constructed with the very tools it rejects – it is an act of artifice (written in rhymed iambic tetrameter) but does not feel artificial. The language itself is “straight up” – it’s clean and clear. Again, Ponsot finds a modern vocabulary and tone, and she yokes it – gently – to form. Ponsot’s ability to do this in poem after poem inspired the critic Angela O’Donnell to say, “As with the practiced athlete or dancer, she makes achieved grace seem natural….”

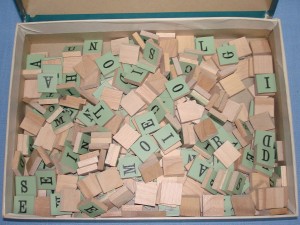

Not only does Ponsot do well with received forms, she invents forms of her own. The tritina, a compressed form of the already-difficult sestina, is a case in point:

LIVING ROOM

The window’s old & paint-stuck in its frame.

If we force it open the glass may break.

Broken windows cut, and let in the cold

to sharpen house-warm air with outside cold

that aches to buckle every saving frame

& let the wind drive ice in through the break

till chair cupboard walls stormhit all goods break.

The family picture, wrecked, soaked in cold,

would slip wet & dangling out of its frame.

Framed, it’s a wind-break. It averts the worst cold.

Following the rules for that form is groan-inducing, unless you do it, as Ponsot does, for pleasure. There are three tercets, with repeating end-words as follows: ABC, CAB, BCA. The envoi – a single line – must include all those end words in their original ABC order. Like I said, it’s torture unless you think it’s fun. If you’re game, try writing one. Produce anything that makes sense and sounds like normal English, both syntactically correct and fluid. Make sure it obeys the rules. Pay attention to sound. Make it musical. If you can do it as gracefully as Ponsot does, and enjoy it as you do it, my hat is off to you. “The delicious realization that what someone’s reading aloud is a sestina gives you a little kick in the back of your ear,” says Ponsot of the form that causes much teeth-grinding to lesser poets. “Some other use of the word six lines away, it’s really very pleasant.”

Though this next poem does not follow a formal pattern of rhyme, Ponsot uses her modern voice effectively to offer up an ancient myth:

DRUNK AND DISORDERLY, BIG HAIR

Handmaid to Cybele,

she is a Dactyl, a

tangle-haired leap-taking

hot Corybantica.

Torch-light & cymbal-strikes

scamper along with her.

Kniving & shouting, she

heads up her dancing girls’

streaming sorority, glamorous

over the forested slopes of Mt. Ida

until she hits 60 and

loses it (since she’s supposed

to be losing it, loses it).

her sickle & signature tune. Soon

they leave her & she doesn’t care.

Down to the valley floor

scared she won’t make it, she

slipsides unlit to no rhythm,

not screaming. But now she can

hear in the distance

some new thing, surprising.

She likes it. She wants it.

What is it? Its echoes originate

sober as heartbeats, her beat,

unexpected. It woos her.

The rhythm’s complex

–like the longing to improvise

or, like the Aubade inside Lullaby

inside a falling and rising

of planets. A clouding. A clearing.

She listens. It happens.

between her own two ears.

Come to think of it, that poem has some rhythmic patterns that make it sound almost Anglo-Saxon. Seamus Heaney reproduced that drum-beat of Old English in his translation of Beowulf (two beats on each side of a central caesura):

…sand churned in the surf, warriors loaded

a cargo of weapons, shining war-gear

in the vessels hold, then heaved out

away with a will in the wood-wreathed ship.

Over the waves, with the wind behind her,

and foam at her neck, she flew like a bird….

In her short poem, Ponsot does something similar, though she breaks the full-line drumbeat into two lines each. If we put her lines back into a single-line format, it looks (and sounds – boom-boom, boom-boom) like Heaney:

Handmaid to Cybele, she is a Dactyl,

a tangle-haired leap-taking hot Corybantica.

Torch-light & cymbal-strikes scamper along with her.

Kniving & shouting, she heads up her dancing girls’

streaming sorority….

Also like Heaney, and like the original poet of Beowulf, Ponsot uses strong alliteration (“Someone takes over / her sickle & signature tune. Soon ….”) along with kennings (the riddle-like renaming of things via the hyphenating of two dissimilar nouns, such as Heaney’s translated “whale-road” to mean the sea, and Ponsot’s “torch-light and cymbal-strikes” to mean lightning and thunder.)

The last line of Ponsot’s poem feels wrong at first, since the rhythm is broken by inserting the word “own.” Without it, the rhythm would be perfect – two beats on each side of the caesura (“She listens. It happens / between her two ears.”) Instead, Ponsot breaks the back of the form. So – is it a misstep? Well, sometimes relaxing the rhythm of a poem can be the sign of mastery – and right there within the poem, Ponsot explains it to us: “The rhythm’s complex /–like the longing to improvise.” It’s “her beat,” it’s “unexpected,” a little nod to her own improvisational skill.

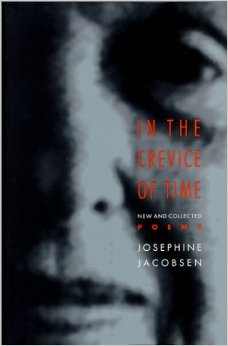

I said that putting the photo of Ponsot with her children at the opening of this piece was risky. It’s also risky to call any poet “undersung” who has had so many poets and critics sing her praises. Josephine Jacobsen (herself a “poet’s poet” and somewhat undersung) was a long-time champion of Ponsot’s work, citing her “powerful, and hence relaxed, ability to play with language, to fuse the witty with the grave.” Louis McKee called Ponsot “an important but often overlooked writer.” Since winning the National Book Critics Circle prize for her third book (The Bird Catcher) in 1998, she has received more media attention and many fine awards, including the Delmore Schwartz Memorial Award, the Shaugnessy Medal from the Modern Language Association, and the Ruth Lilly Award for lifetime achievement (with its whopping $100,000 prize.) She was elected a Chancellor of the American Academy of Poets in 2010.

So why isn’t her work better known? What keeps a writer from connecting to a wider audience? Maybe wordplay – one of Ponsot’s fortes – confuses readers. Maybe formal elements scare or irritate them (one reason why Billy Collins’ clever poem, “Paradelle for Susan,” which mocks demanding poetic forms, is so popular.) And maybe we have a skewed idea of what makes a poet “great.” Consider this description of “Greatness” by David Orr, who writes the “On Poetry” column for the New York Times:

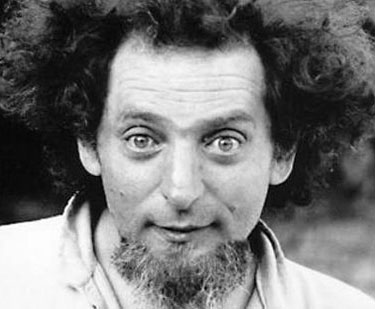

What, then, do we assume ambition and Greatness look like? There is no one true answer to that question, no neat test or rule, since unconscious assumptions are by nature unsystematic and occasionally contradictory. Generally speaking, though, the style we have in mind tends to be grand, sober, sweeping—unapologetically authoritative and often overtly rhetorical. It’s less likely to involve words like “canary” and “sniffle” and “widget” and more likely to involve words like “nation” and “soul” and “language.” And the persona we associate with Greatness is something, you know, exceptional—an aristocrat, a rebel, a statesman, a prodigious intellect, a mad-eyed genius who has drunk from the Fountain of Truth and tasted the Fruit of Knowledge and donned the Beret of….Well, anyway, it’s somebody who takes himself very seriously and demands that we do so as well. Greatness implies scale, as I mentioned earlier, and a Great poet is therefore a big sensibility writing about big things in a big way.

Sarcasm aside, Orr makes an important point about scale. Is it possible for someone like Marie Ponsot, somewhat casual about her career as a poet, and equally charmed by motherhood as by professional success, to gain access to the inner circle? Does Ponsot write about “big things in a big way?” or is there too much of the kitchen and garden, of children and grandparents, in her work to satisfy anthologists who help determine reputations? Who determines what the “big things” are? Even more important, does it matter to Ponsot? As she said once during the previously mentioned PBS Newshour, “… when you get to be 80, you can say about a lot of things that used to cause you anxiety, ‘I don`t care. I just do not care. There are things I care about, but all this worrisome stuff, no, I don`t care.’ ”

Not caring enough about being praised could be to blame. Or is the problem simply the lack of a steady stream of books? How long can a writer’s reputation remain suspended above the Earth without some gravitational pull being exerted? For twenty-five years, Ponsot not only did not publish collections but did not send individual poems out for publication in reviews. Once she began publishing again, urged on by her friend, the poet Marilyn Hacker, the time between books averaged eight years.

That doesn’t mean she stopped writing and thinking about language while her main focus was on raising her children. In an interview with Anna Ross, Ponsot says this:

My first baby was my girl—I had one girl and six boys. [One day] I walked into her bedroom in the morning and I realized that that little noise that she was making in the morning was the shape of that sentence that I always said to her. We were speaking French at that point because my ex-husband had no English, and I was going into the room and I was saying “Òu elle est, Monique,” and there she was saying “dah-dah-dah-dah-dah.” She’d been doing it for days, and I hadn’t recognized it. I was so ashamed of myself, I didn’t know what to do. It was a great moment of celebration, because I realized that the shape of a sentence is a music that she was reproducing. Like everyone who is still living in the purely oral tradition, she had no idea that a sentence was composed of different words; it was all one little tune. She was babbling out her little tune to me. Oh God, it was so thrilling. It was one of the great days of my life.”

What do we want our writers to care about? Praise? Reputation? Productivity? Some poets, after all, manage to publish often and even to earn back their book advances. Mary Oliver, one of America’s most popular poets, has published twenty-nine books in fifty years, and that includes a nine-year gap between her first book in 1963 and her second in 1972. If you do the math on this one and start the count in 1972, her output averages one book every 17-18 months. Billy Collins, another wildly popular poet, has published ten collections since 1995 (the date of his breakthrough collection, The Art of Drowning.) Ten books in eighteen years – one every couple of years.

But being prolific can’t explain everything about popular success. Some of it has to do with accessibility, which both Oliver and Collins excel at. Few readers say of an Oliver or Collins poem, “I don’t get it.” But Ponsot’s poems, despite their modern diction, are not always easily understood. She brings a razor-sharp intelligence to the task of writing, along with her wit, and intelligence can send us scurrying to reference books or to Wikipedia for clues (Cybele? Dactyla? Corybantica?) A keen intellect can assign some poets to the dreaded “Academic” file forever, especially in the United States (God save intellectuals in 21st-century America.)

Some of it – the achievement of name-recognition status – has to do with whether a poet is easily classifiable. Readers want to know: Is this a nature poet, a funny poet, a regional poet, a feminist poet? It’s difficult to pigeon-hole Ponsot – her poems include references to myth and medieval iconography but do strange Beat-Generation things to syntax sometimes and send out hipster vibes. She can be funny, political, lyrical, light, heavy, post-modern, formal and free-wheeling, but she is not consistently any of them.

And certainly, writers who stay afloat in terms of reputation are willing to self-promote and to indulge in the networking that connects them – via readings and workshops and signings and conferences and and and — with insiders in the world of media and publishers. Ponsot, in a 2003 interview with Benjamin Irvy, had this to say about her interrupted career: “I was very busy. It’s really that I was entirely out of all those professional poetry loops. That’s worth saying, because it’s easy to keep writing without tremendous agitation in whatever time you have. If you don’t imagine yourself as a career poet but rather as a person who writes poems, you can just go on doing that.” She goes on to say, “You really have to believe me when I say my dissociation from the idea of publication was not deliberate, contemptuous or passive-aggressive; it just didn’t occur to me. Think of all those seventeenth-century cavalier poets who had no interest in publishing their work – it didn’t occur to them either. Frequent publication of poems is a nineteenth-century development.”

Ponsot did not, during those quiet years, consider herself a “career poet.” Rather, she saw herself – at least for a long period of her life – as simply “a person who writes poems.”

In 2010, Marie Ponsot suffered a stroke which impaired both her speech and her memory, two things which made her the unique poet she is. She has been struggling against those limitations; her still-strong religious beliefs (she is a life-long Catholic) sustain her. Her Catholicism might also explain the seven children, sixteen grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren. At the center of a large family, Ponsot still thinks of the power of poetry to keep her company: “…it’s a very enjoyable thing,” she says, “to be an old writer. It’s bliss! It’s really a highly entertaining state. You manage as long as language lasts. And language lasts a long time. Language is a sturdy companion, I think.”

I’ll leave you with one last poem by Marie Ponsot, taken from her book, The Green Dark:

THE IDES OF MAY

Every seventh second the wood thrush

speaks its loose curve until in ten minutes

the thicket it lives in is bounded

by the brand of its sound.

Every twenty-eight days the leisurely

moon diagrams the light way, east to west,

to describe mathematics and keep us unstuck

on our arched ground.

Every generation the child hurries out of child-

hood head bared to the face-making blaze

of bliss and distress, giving a stranger power to

enter, wound, astound.

The dedication of that poem reads “For my children entering parenthood.” In that poem I see and hear a big sensibility writing about big things in a big way. Maybe success doesn’t depend on timing, productivity, accessibility, or pigeon-hole-ability. Maybe it just depends on how we define “big.” And how we define “success.”

—Julie Larios

————————————————-

Julie Larios is the author of four books for children: On the Stairs (1995), Have You Ever Done That? (named one of Smithsonian Magazine’s Outstanding Children’s Books 2001), Yellow Elephant (a Book Sense Pick and Boston Globe–Horn Book Honor Book, 2006) and Imaginary Menagerie: A Book of Curious Creatures (shortlisted for the Cybil Award in Poetry, 2008). For five years she was the Poetry Editor for The Cortland Review, and her poetry for adults has been published by The Atlantic Monthly, McSweeney’s, Swink, The Georgia Review, Ploughshares, The Threepenny Review, Field, and others. She is the recipient of an Academy of American Poets Prize, a Pushcart Prize for Poetry, and a Washington State Arts Commission/Artist Trust Fellowship. Her work was chosen for The Best American Poetry series by Billy Collins (2006) and Heather McHugh (2007) and was performed as part of the Vox series at the New York City Opera (2010). Recently she collaborated with the composer Dag Gabrielson and other New York musicians, filmmakers and dancers on a cross-discipline project titled 1,2,3. It was selected for showing at the American Dance Festival (International Screendance Festival) and had its premiere at Duke University in July, 2013.

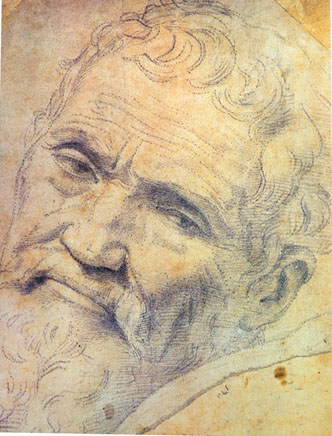

Sketch of Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra, 1533

Sketch of Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra, 1533 …………Michelangelo’s David

…………Michelangelo’s David