You searched for Glenn Gould | Numéro Cinq

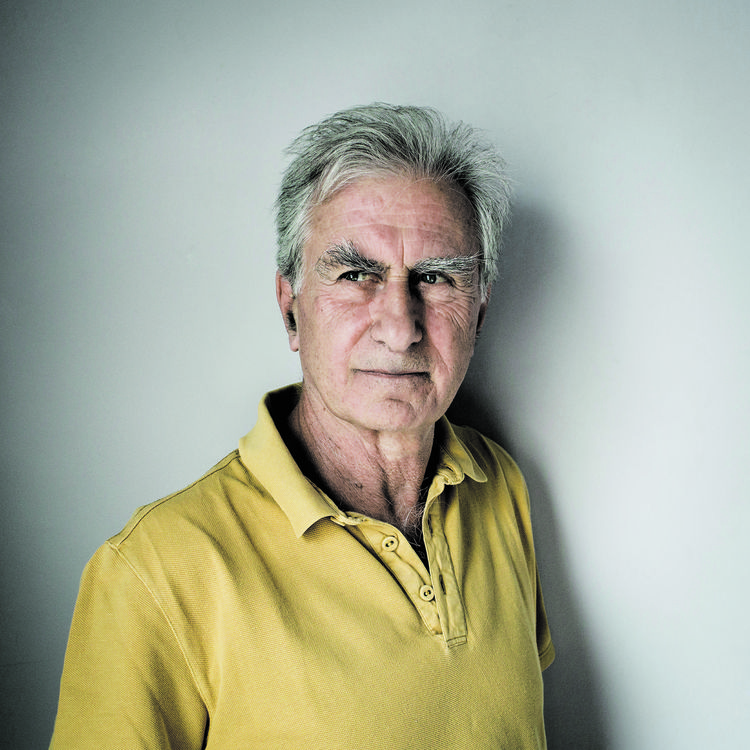

Allan Cooper by Frédéric Gayer

Allan Cooper by Frédéric Gayer

x

Just to whet your appetite. These are brand new poems by Allan Cooper. One of them — “I Have My Silence” — will be published in his imminent collection Everything We’ve Loved Comes Back to Find Us to be published by Gaspereau Press in April.

EVENING PRIMROSE

How often they’ve come back to me

in the tall house of summer

like the scent of the evening primrose

rising from the earth

men and women who worked the fields

and woods and kitchens,

who dreamed and loved and despaired

the same as we do, who held new infants

in their arms and rocked them

by oil light burning down

to a small flame, the rhythms

of their conversations

gone out further now

than any star we will ever see.

My grandfather opens

the woodshed door, a pail

in his hand, walking to the fields

where he will dig the new potatoes

before the heavy rains. My grandmother–

who at eighty taught me how

to clean the spring head

where the water flowed from bedrock–

is singing to me through my fever, her voice

mingling with the sound of the brook.

I swear my small body rose above the house

and looked down on the black roof,

the winglike shadows cast across the lawn

as if someone would come and carry me

x

away, and maybe they almost did.

When my fever broke, I could feel the damp

cloth on my forehead, replaced again

and again throughout the night.

I could hear my grandparents

talking low in the kitchen. It’s good

when they come back to find us, hold us,

guide us. They loved us unconditionally.

Someone places a hand on my forehead,

then their footsteps fading down the hall

as I drift in the sound of the running spring,

the deep sleep of boyhood.

x

x

GLENN GOULD PLAYING

My moods are more or less inversely related to the clarity of the sky

—Glenn Gould

Glenn Gould, in large rimmed glasses, is stooped low over the

piano

like a rider on a horse. His face is what music looks like

when it takes on a human form. His fingers are ten reins guiding

the notes,

eighty-eight of them, low notes as if rising from Hades,

high notes like the feminine tone of spring.

His hands change positions, the right playing the low notes

quickly,

like fox sparrows suddenly arriving in spring, the sounds

that a human heart makes when it’s totally in love with the

world.

Glenn Gould is playing, and he seems a little unsteady in the

saddle,

his chair a bit rickety, as if it might fall at any moment;

but it doesn’t, and he hovers so close to the keys he can taste

them,

coaxing the flavour and fragrance from each note. Now he’s

singing to the keys,

like a monk saying prayers, and the notes move faster,

almost too fast for us to follow;

it’s as if the piano could resonate at a certain frequency

and suddenly implode, the strings collapsing on the sound board,

the sound board falling through the wooden frame…

Things grow softer. These are notes we’ve heard before, but never

so gently,

feathery, like a father singing to a child, the last words we’ll say

to someone,

an entire barren field suddenly filled with volunteer poplars.

The notes begin to chase each other. They are waves breaking

over waves

on the shore of Lake Superior, thousands of neutrinos moving

through our bodies

at once. It’s a Bach fugue, and the sound is like losing yourself in

something

for the first time, the sound of cells dividing, and you’re nameless

again

as you were the moment you were born.

Glenn Gould is playing, and for the black horse of the piano

there is only one rider, and for that rider

there is only the light drawn from the gloom

and darkness clinging to the edges of the light.

x

x

THE SNAIL AND THE ROSE

Is there a symbiotic relationship between these pale yellow-

green snails and the old Irish roses? This one has climbed over

three feet up a stem which is guarded by thorns that would

pierce my finger if I grasped it. The snail is about the size of a

quarter, although there’s no money in this snail’s life. He lives for

free, as most things do on this planet. I’ve seen them before,

clinging to a leaf, or making their way up through a wild jungle

of leaves.

More and more it is the quiet things around me that give me

pleasure. If this snail makes any music, or has a voice, I can’t hear

it. He lives in the heaven of his day, carrying his house on his

When he dies the house will be left behind a little while, like

the spinsters’ house with grey clapboard, the dolls in the cedar

chest still waiting for the whisper of a child.

x

x

THE APPLE TREE

—in memory of Galway Kinnell

One afternoon in the 1940s, in summer,

a car from the Boston States or the Carolinas

or the tip of the Florida Keys

drove by this gravel bank,

and someone opened a car window

and threw out an apple core, that landed

precisely here, and one dark brown

seed, the oval of a water shrew’s eye, took root

and began to grow, at first a thin, small question,

then a wiry, almost defiant voice…

Its thick, squat trunk is as shaggy as a Shetland pony,

wild as those Zen Buddhist monks

who sit quietly, cross-legged,

smiling inwardly.

In late May or early June

the blossoms begin to open from taut buds,

at first a rosy pink, then

a rich whiteness blending in,

like cream poured into a china bowl.

And when the rain falls, the leaves

make a tapping sound,

like someone knocking lightly

at a door, someone who has

come a long way to be here, now,

in this world; someone rich

with the odour of spring, pungent

as wet earth, the first blades

of new grass, the smell of bark,

like an old keeper of small horses.

And an old woman, rich in perfume

that carries with it

rosewater to an altar

where the earth is worshipped,

and the transformation that will happen

when a winged one comes near

and enters a blossom…

A grandmother, who loved Evening in Paris,

gathered apples from the wild trees each fall

and carried them in buckets or bowls

to her steaming autumn kitchen;

she made apple sauce, apple

pies, apple strudel, apple crisp,

and baked apples in brown sugar,

where nothing is wasted.

So many wild trees at the side of the road,

in ditches, in sudden meadows and clearings,

growing from stone walls, cellar holes,

through ribs and femurs

gathered back by the earth.

And for every ancient tree that

falls, another takes its place,

and another, in the long lineage

of trees, one ring at a time, one

blossoming and fading at a time.

Apples ripen, and the deer come,

and some stand on their hind

legs like men reaching up

into the highest branches for

the sweetest and most coveted apples,

which have been kissed by the sky.

Old apple trees that, if they were love poems

would be both male and female, male and male,

or two young girls holding hands beneath the branches

as the rain comes down

on a day that will never end for them.

A day when the blossoms were ready

to fall, and high up

in the branches

three dozen cedar waxwings in a row,

and as one petal fell

it was taken in the beak of the nearest bird

and passed to the next,

and the next, male to male,

male to female, until it reached

the last waxwing at the end

of the branch, and she ate it…

Not one thing is wasted,

not one petal or word, like these words

that I pass to you now: compassion,

care, tenderness, hope, joy,

forgiveness; and love, that final word

at the end of our branch, the end of our rope,

that stubborn word we carry with us,

tough as a seed, the best for last.

x

x

I HAVE MY SILENCE

I’ve lived a good time.

Not as long as a saguaro cactus

or a sequoia, but a good time.

One second can last a thousand years.

And no amount of study or joy can prepare us

for the ecstasy that Rumi and Mirabai felt.

I’ve seen and felt things

and remained silent.

I’ve watched the fox sparrows migrating in fall

and kept quiet, although inside

I’ve felt a wing rising,

moving out across the waters.

The last thing I like to do

at the end of the day

is walk out and greet the dusk.

I say nothing.

But I might just show

this multi-coloured coat

like Joseph’s, woven from everything

I’ve ever loved. Can you see it?

I’ve lived a good time.

I have work to do. I have my silence

as the sky does

every morning when the sun breaks over the hills.

—Allan Cooper

x

x

Allan Cooper has published fourteen books of poetry, most recently The Deer Yard, with Harry Thurston. He received the Peter Gzowski Award in 1993, and has twice won the Alfred G. Bailey Award for poetry. He has also been short-listed three times for the CBC Literary Awards. Allan intermittently publishes the poetry magazine Germination, and runs the poetry publishing house Owl’s Head Press from his home in Alma, New Brunswick, a small fishing village on the Bay of Fundy.

x

x

Seiji Ozawa, left, and Haruki Murakami. Credit Nobuyoshi Araki (NY Times)

Seiji Ozawa, left, and Haruki Murakami. Credit Nobuyoshi Araki (NY Times)

Absolutely on Music is the kind of book that makes you want to go find the music for yourself… These conversations left me wanting more, in the best possible way. They made me want to go sit with a friend in the living room, listening to records, one after another, late into the evening. —Carolyn Ogburn

Absolute Music

Haruki Murakami & Seigi Ozawa

Knopf, 2016

352 pages; $27.95

“…all I want to say is that Mahler’s music looks hard at first sight, and it really is hard, but if you read it closely and deeply with feeling, it’s not such confusing and inscrutable music after all. It’s got all these layers piled one on top of another, and lots of different elements emerging at the same time, so in effect it sounds complicated.” —Seiji Ozawa, Absolutely on Music

.

Absolutely on Music, by novelist and music aficionado Haruki Murakami and legendary conductor Seiji Ozawa (translated by Jay Rubin) is the best kind of eavesdropping. Although the book is (not inaccurately) described as series of “conversations,” the topic throughout is music, and the conversations appropriately become Murakami’s interviews of Ozawa regarding his long and storied career in the aftermath of diagnosis of esophageal cancer. Ozawa explains that “until my surgery, I was too busy making music every day to think about the past, but once I started remembering, I couldn’t stop, and the memories came back to me with a nostalgic urge. This was a new experience for me. Not all things connected with major surgery are bad. Thanks to Haruki, I was able to recall Maestro Karajan, Lenny, Carnegie Hall, the Manhattan Center, one after another…”

Murakami (b. 1949) is best known as a novelist, including Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World (1985) The Wind-Up Bird Chronicles (1994) and 1Q84 (2009-2010). He has received many awards for his work, including the Franz Kafka Prize and the Jerusalem Prize. He has published several collections of short stories and many works of nonfiction, including Underground, about the sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway, and What I Talk About When I Talk About Running. Music often plays a strong role in Murakami’s writing. Scholars have long been drawn to exploring the musical worlds evoked in Murakami’s novels; they’ve created playlists and written dissertations (and created more playlists. There is even a special resource on Murakami’s website that provides references to the musicians, songs, and albums mentioned in his writing. The biography of Murakami written by his long-time translator, Jay Rubin, is titled Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words.

“How did I learn to write?” Murakami asks. “By listening to music. And what’s the most important thing in writing? It’s rhythm.”

Murakami’s and Ozawa’s daughters were friends, but the two artists only knew one another casually. They never spoke of their work to one another until Ozawa became ill with esophageal cancer in December, 2009. Because Ozawa had to limit his work, Murakami noted a new eagerness when they met to turn conversations to the topic of music, noting that it might have been the fact that he was not talking to a fellow musician that “set him at ease.” The task of publishing these conversations came from a story Ozawa told Murakami about Glenn Gould and Leonard Bernstein’s 1962 performance of Brahms’ First Piano Concerto. Murakami writes, “’What a shame it would be to let such a fascinating story just evaporate,’ I thought. ‘Somebody ought to record it and put it on paper.’ And, brazen as it may seem, the only ‘somebody’ that happened to cross my mind at the moment was me.”

Seiki Ozawa (b. 1935) began conducting as a boy in Japan when a rugby injury sprained his hand too badly for him to continue his piano studies. His skill soon brought him to the United States, where in 1960 he won first prize for student conducting at the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s Tanglewood festival. The young Ozawa studied conducting under legendary conductors such as Herbert von Karajan and Leonard Bernstein, who both figure prominently in these conversations. He went on to serve as the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra for 29 years, and as the principal conductor of the Vienna State Opera. He has received many honors and awards, including a Kennedy Center Honor and two Grammy Awards.

It’s interesting to note that the collection opens with a discussion of who is really in control during a performance of a concerto: the soloist or the orchestra’s conductor? Murakami initiates these interviews not with Ozawa’s own recordings, but with a discussion of Bernstein’s well-known disavowal of the interpretation of the Brahms First Piano Concerto as performed by Glenn Gould and the New York Philharmonic in 1964. Bernstein spoke to the audience prior to the performance, saying:

I cannot say I am in total agreement with Mr. Gould’s conception, and this raises the interesting question: “What am I doing conducting it?” [Audience murmurs, tittering.] I’m conducting it because Mr. Gould is so valid and serious an artist that I must take seriously anything he conceives in good faith, and his conception is interesting enough so that I feel you should hear it too.

Gould often performed with tempi so eccentric that it was difficult to regulate his interpretation together with that of the orchestra. It was this that prompted a discussion between Murakami and Ozawa as to which artist, conductor or soloist, was really in charge of a performance. But in this dialogue of two renowned artists, Seiji Ozawa and Haruki Murakami, who is in charge?

Though it is Ozawa’s history, the book ultimately belongs to Murakami. The comparison to Glenn Gould is an apt one, I feel, for Murakami’s prosody is, like Gould’s musical syntax, both engaging and strongly idiosyncratic. The language is unmistakably Murakami’s throughout. The syntax and rhythm of the words (at least as translated by long-time Murakami translator Jay Rubin) could be lifted straight from the page of any Murakami novel. I kept feeling as if a cat were gazing silently from the other room. If you are a fan of Murakami’s prose, then you will enjoy this book as well.

The conversational settings (the book consists of six conversations, separated by shorter “interludes”) are described only in the loosest terms. The first conversation, for example, takes place in Murakami’s home “in Kanagawa Prefecture, to the west of Tokyo.” Albums and CDs are pulled off the shelf to play as they talk, but the shelves themselves are never described; it’s as if they are being pulled from thin air. There’s something of the animated drawing about these conversations, the way that the suggestion of a particular recording prompts an immediate search for music. In the example here, the search is immediate. Though we haven’t any idea where the two are seated (or if they are seated), no sense of the room, or the light, the time of day or night, the mention of Lalo’s piece for orchestra and solo violin initiates a small flurry of activity:

Ozawa: “We [the violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter and Ozawa] Lalo’s Spanish something-or-another. She was barely twenty years old at the time.

Murakami: Edouard Lalo’s Symphonie Espanole. I’m sure I’ve got a copy of that somewhere.

Rustling sounds as I hunt for the record, which finally turns up.

Ozawa: This is it! This is it! Wow, I haven’t seen this thing for years.

Here, too, you get a sense of the way in which Murakami, the first-person author, enters the page as himself rather than via the transcriptionist of his own words. He’s “Murakami” except when making “rustling sounds” as he searches for the record he has in mind, which “finally turns up.” Those details—unexplained rustling, the “finally turns up,” which insists on being read with a kind of drama whose merit is uncertain—is classic Murakami.

There’s no doubt, however, that Murakami knows his stuff. As Ozawa himself puts it in the book’s afterward, “I have lots of friends who love music, but Haruki takes it way beyond the bounds of sanity. Jazz, classics: he doesn’t just love music, he knows music.”

One of the most fascinating aspects of this dialogue comes through the two very different ways in which they’ve each come to know the music that they love. For Murakami, his knowledge of music comes through avid and detailed listening to recorded music, supplemented by live performances when possible. As he admits, “a piece of music and the material thing on which it was recorded often comprised an indivisible unit.”

Ozawa, on the other hand, is far less familiar with recorded works, even his own. His knowledge of music comes from his study of it. His first encounter with Mahler was through reading a score: “I had never heard them on records. I didn’t have the money to buy records then, and I didn’t even have a machine to play them on.” The music itself was revelatory, “a huge shock for me—until then I never even knew that music like that existed…I could feel the blood draining from my face. I had to order my own copies right then and there. After that, I started reading Mahler like crazy—the First, the Second, the Fifth.” The first time he ever heard Mahler performed was as Bernstein’s assistant at the New York Philharmonic. Because of the way in which he learned the repertoire, Ozawa, unlike Murakami, was less familiar with the range of recorded performances of any given piece. Murakami is struck by what he calls “the fundamental difference that separates the way we understand music.” He finds that difference between a music-maker and a music lover to be an almost-literal wall, “especially high and thick when that music maker is a world class professional. But still, that doesn’t have to hamper our ability to have an honest, direct conversation. At least, that’s how I feel about it, because music is a thing of such breadth and generosity.”

The first conversation revolves around a variety of recordings of Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto. A 1957 performance with Glenn Gould and the Berlin Philharmonic under the baton of Herbert von Karajan is compared with Gould’s recording with Leonard Bernstein and the Columbia Symphony Orchestra (composed of members of the NY Philharmonic) in 1959. The two then listen to Rudolf Serkin’s recording of the same concerto with Bernstein in 1964, which is taken at such a rapid tempo that Ozawa exclaims in astonishment, “It’s kind of an inconceivable performance.” They listen to another recording on period instruments, or the actual instruments for which Beethoven would have been writing: Jos van Immerseel performing on the fortepiano, rather than the modern-day piano, for instance. (Oddly, neither the orchestra nor the conductor is named.) This performance provokes the kind of observation that will delight the serious student of music, or anyone who enjoys thinking about sound: Ozawa says, almost as an aside, that in this period-instrument recording that “you can’t hear the consonants.”

Ozawa: The leading edge of each sound.

Murakami: I still don’t get it.

Ozawa: Hmm, how can I put it? If you sing a-a-a, it’s all vowel. But if you add consonants to each of the a’s, you get something like ta-ka-ka, or ha-sa-sa. It’s a question of which consonants you add. It’s easy enough to make the first ta or ha, but the hard part is what follows. If it’s all consonant—ta-t-t—the melody falls apart. But the expression of the notes changes depending on whether you go ta-raa-raa or ta-waa-waa. To have a good musical ear means having control over the consonants and the vowels. When the instruments of this orchestra talk to each other, the consonants don’t come out.

Murakami next brings out the 1982 recording of the piece with Rudolph Serkin again at the piano, and Ozawa himself conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Here, we’re privy to Ozawa’s self-critique—“Now, this is ‘direction.’ Hear those four notes? Tahn-tahn-tahn-tahn….I should have done more of that.”—and his suggestion that Serkin, who was now late in life, realized that it was probably “his last performance of this piece, that he won’t have another chance to record it while he’s alive, and so he’s going to play it the way he wants to. Period.”

Finally, they listen to Mitsuko Uchida’s 1994 recording with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra under the baton of Kurt Sanderling. Earlier, the two have discussed the use of silence (the Japanese use the word ma to describe this quality) and the way in which Gould uses ma so naturally in his interpretation. Now they find a similar quality in Uchida’s playing, the silent intervals, her “free spacing of the notes.”

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No.3 / Mitsuko Uchida, Seiji Ozawa. Saito Kinen Orchestra

This concept of ma comes back as Ozawa describes to Murakami the conductor’s role in bringing the orchestra in following a break in the sound:

Murakami: When you’ve got an empty moment and you have to glide into it, the musicians all watch the conductor, I suppose?

Ozawa: That’s right. I’m the one responsible for putting it all together in the end, so they’re all looking at me. In that passage we just heard, the piano goes tee…and then there’s an empty space [ma] and the orchestra glides in, right? It makes a huge difference whether you play tee-yataa or tee…yataa. Or there are some people who add expression by coming in without a break: teeyantee. So if you do it by kind of “sneaking in” as they say in English, the way we heard, it can go wrong. It’s tremendously difficult to make the orchestra all breathe together at exactly the same point. You have all these different instruments in different positions on the stage, so each of them hears the piano differently, and that tends to throw off the breath of each player by a little. So to avoid that kind of slip-up, the conductor should come in with a big expression on his face like this—teeyantee.

Murakami: So you indicate the empty interval [ma] with your face and body language.

Ozawa: Right, right. You show with your face and the movement of your hands whether they should take a long breath or a short breath. That little bit makes a big difference….it’s not so much a matter of calculation as it is the conductor’s coming to understand, through experience, how to breathe.

Each conversation focuses very loosely on a topic, but the strength of this book is found in its soaring, tangential details. The second conversation revolves around Ozawa’s performances of the Four Brahms Symphonies with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the manner of organization within orchestral groups today, particulars of instrumentation in the horn section of Brahms’ First Symphony; Brahms evokes Ozawa’s mentor, Hideo Saito. Ozawa’s Saito Kinen Orchestra was formed to mark the 10th anniversary of the great conductor’s death. The third conversation revolves around Ozawa’s experiences during the 1960s as he moves from New York Philharmonic, where he was assistant to Leonard Bernstein, to working with the Chicago Symphony, to three recordings Ozawa made with the Toronto Symphony of Berlioz’ Symphonie Fantastique.

Seiji Ozawa conducts Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique, Toronto Symphony Orchestra 1967. 1st Movement: Rêveries – Passions.

In the fourth conversation, the two discuss the works of Gustav Mahler, a composer who’s work wasn’t widely performed until Leonard Bernstein championed his works in the 1960s. Of course, Murakami explains, one of the reasons Mahler wasn’t performed was that his work, like the works of all Jews, was “quite literally wiped out over the twelve long years following 1933, when the Nazis took power, to the end of the war in 1945.”

This is a fascinating dissection of both the composition and orchestration of Mahler’s nine symphonies and a history of the performance styles that were used over the decades that Ozawa has been conducting them. The emerging prevalence of recordings actually changed the performance styles; as recording moved away from recording the overall sound, focusing instead on individual instruments, so too did the tendency of orchestras to aim for a more transparent, detailed performance. The whole chapter on Mahler is one of the richest in the book. Yet, here’s Murakami, breaking in again to note Ozawa “eats a piece of fruit.”

Ozawa: Mmm, this is good. Mango?

Murakami: No, it’s a papaya.

Other times, Murakami’s interruptions are to provide poetic interpretation that comes in surprising passages, however lovely his descriptions may be. For example, while listening to the third movement of Mahler’s First Symphony, Murakami notes that “the clarinet adds an indefinably mysterious touch to the melody, the strange tones of a bird crying out a prophecy deep in the forest.” The line here, not unlike the mysterious touch of the clarinet, is surprising only because it is so rare; it’s a language from another time. In this book, the magic comes from two skilled craftsmen talking about their work with curiosity and affection.

The fifth conversation revolves around Ozawa’s experiences conducting opera, both staged and in concert performances. He recalls being “booed in Milan” at La Scala. Murakami presses him, asking twice, “Do you think there was some resistance to the idea of an Asian conducting Italian opera at La Scala?”

Osawa replies, “The sound I gave Tosca was not the Tosca they were used to.”

“Back then, weren’t you the only Asian conducting at a first-class European opera house?”

“Yes,” says Ozawa. “I suppose I was.”

That the two men are both Japanese, conversing in Japanese, is an issue that glides just below the surface of the conversation. Many times, Ozawa credits his lack of English fluency to explain why he simply didn’t notice the political waters in which he swam as a young conductor in New York and Europe. When he recalls the days in which Ravinia, the prestigious music festival outside of Chicago, was an all-white establishment (in the context of bringing Louis Armstrong to the festival), neither acknowledge that his very presence contradicts the memory of “all white”.

The final conversation centers on the Seiji Ozawa International Academy Switzerland. It’s a summer chamber music program that works with promising young musicians in small ensembles and extraordinary master instructors such as violinist Pamela Frank, cellist Sadao Harada, violist Nobuku Imai, and violinist Robert Mann. It’s a program designed around the very principles Ozawa learned from his first teacher, Hideo Saito.

Reading Conversations on the subway, or a cafeteria, or a picnic table in the late autumn sun, I could usually call to mind some of the music under discussion from memory, down to the scratchy sound of cracks in the vinyl, the thick humidity of the needle tracing silence between movements, as if it were playing just a the limit of earshot. But when I sat down to write about the book, I felt compelled to search out the actual recordings. I found many of them on Murakami’s website, which (as I mentioned earlier) contains playlists of works referenced in his other books. Other pieces, though not all, can be found online. These conversations left me wanting more, in the best possible way. They made me want to go sit with a friend in the living room, listening to records, one after another, late into the evening.

—Carolyn Ogburn

Carolyn Ogburn lives in the mountains of Western North Carolina where she takes on a variety of worldly topics from the quiet comfort of her porch. She’s a contributing writer for Numero Cinq and blogs for Ploughshares. A graduate of Oberlin Conservatory, UNC-Asheville, and UNC School of the Arts, she recently finished her MFA at Vermont College of Fine Arts and is currently seeking representation for her first novel.

.

Camilo Carrara (1968) is a musician based in Sao Paulo, Brazil whose work refuses to be categorized. His recordings range from classical to popular and jazz, and anywhere in between. Though he’s often described – accurately – as a guitarist, he plays, arranges and composes for many instruments, including 12-string guitar, mandolin, electric guitar, and other strummed instruments. He is also a teacher and a Sound Branding Consultant. He has done more than sixty solo and ensemble recordings, and his performance career spans three continents. He’s played concerts in Italy, Portugal, Switzerland, USA, Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Venezuela, and throughout Brazil. He teaches guitar at the annual National Music Festival in Maryland, and has been the guest artist and soloist with orchestras throughout Brazil and worldwide.

Carrara also works as a producer, particularly in his long-time work with the HSBC Christmas Concert, one of the largest holiday events in Brazil. Since 2011, he has been the arranger and producer of this concert. At the heart of this event is a children’s choir, 160 children who are the victims of violence or who are orphaned. Carrara has a degree in classical guitar from the University of São Paulo, and is finishing a Masters Degree in Strategic Marketing Management at the São Paulo University School of Economics and Management. He teaches at Faculty Cantareira in São Paulo, and at the Music in the Mountains Festival, in Poços de Caldas, Minas Gerais.

One of the most interesting things about this conversation for me was Carrara’s commitment to creating music that communicates to a broad listenership, and the limitations of a single identity. This is based in part on his background growing up in Brazil where his father was imprisoned and tortured as a result of his political convictions. Carrara spent nine months of 1989 traveling and busking throughout Europe, and was present in Berlin when the wall between East and West Germany was torn down. His career seems to suggest that the walls between traditionally separate musical traditions may not be as permanent as they may seem.

Carolyn Ogburn: As I learned more about you for this interview, I was struck by how many interests you have. It seems to me that in general people – professionals of the music field or any other manner of profession – are required to be specialists these days. But your career has blended popular and classical performance (on guitar, mandolin, and other stringed instruments) as well as teaching, composing and producing, and you’re studying for a graduate degree in marketing. How do you answer the question, “What do you do?”

Camilo Carrara: Carolyn, how interesting you start our conversation with this question. In fact, after studying strategic marketing management for over 2 years, this is an issue for me. After all, it is part of the strategic marketing technique to define well what is the focus of your business and what products you sell. For anyone who is an artist and only moves in the world of arts, sometimes talk about product and market gets to be a heresy. But it doesn’t need to be so.

In fact, I consider myself all that you listed above and depending on the situation, on the context, I respond differently. Sometimes I say that I am a musician. Sometimes I stand as a solo guitarist. But I am also a multi-instrumentalist (mandolin, electric guitar, 12-string guitar, cavaquinho — typical Brazilian instrument used in choro and samba), composer, arranger, improviser, teacher, and music producer. I also work as a music expert on causes court involving copyright and as Sound Branding consultant – the discipline that creates and manages the sonic identity of the brands.

I usually feel good doing many things, despite knowing that this can be risky, professionally speaking. Doing many things have a price and returning to the issue of strategic marketing, I know that my challenge is to communicate all these multiple skills to the public without it look like I’m an imposter (exaggerating a bit), or it seems that I do not know how to do anything well done. The issue of communication is one of my biggest challenges today.

I consider myself very fortunate to have had a very consistent musical training and at the same time I know many of my limitations. All I do is the result of hard study and work and it is very gratifying to be recognized by my peers and also by the general public. In fact, I think it was because of this sort of “more general profile” that I was invited to participate in the National Music Festival in Maryland, in the last five years.

What should be a very short and quick response …

CO: (laughing) I think many artists can relate to your answer…we do many things, I think. Though not always with as much expertise! Do you think there is a push these days to be more diversified as a musician? And – since you’ve been at this for a while, have you noticed any changes in that since your early years as a musician?

CC: I found it curious that to reflect on what it means to be a diverse musician, it reminded me of a great Brazilian literature professor, Alfredo Bosi, with whom I had classes at the university, at the time I was a linguistic student. He spoke a few times about the phenomenon of “repetition” and “novelty.” And this is very interesting and beautiful. According to him, the repetition causes the sensation of comfort as the novelty causes alert feeling. That is, learning to dose these two phenomena is a matter of life. We need both to live. Thinking specifically within the framework of creation, in the framework of the creative world, this is a central issue for composers, writers, painters, etc. But it is also a very useful way to think about demand and understand how the market works: almost everything we do is in order to fulfill the wishes and needs.

I have the feeling that diversity is linked to the concept of the novelty. If contemporary classical composers are looking for other solutions to attract public, for example, it means that they feel that the public is starved for news. Or that they are tired of repeating. In this sense, I see the resemblance to my student days. There has always been this kind of movement: the musicians seek to know what are the interests of the public or the public demand for what is interesting musically.

CC: This event attracts thousands of people every year and was created 25 years ago. It is especially beautiful because the center of attention is a children’s choir. These are children who receive special attention or because they were abandoned or victims of some type of violence. It is a work done with great care throughout the year. Musically speaking the concept is orchestral. It was developed by the conductor of the choir Dulce Primo. She is an amazing person and brought a lot of sophistication for a considered popular presentation. The interesting thing is that she managed to mix very well the influences of classical music with what is richer in Brazilian popular music. It is the meeting of polyphony and the richness of Brazilian rhythms.

My role in this event is to be arranger and producer. It’s a big challenge. I write the orchestral arrangements, record instruments and edit the audio. I take care of all the steps to (record and create) a CD. Several months of preparation to (be heard by) an average of twenty thousand people a day. They estimate that four hundred thousand people attend the show every year. I also study this event from the point of view of the impact of marketing. The concert is sponsored by a major bank and can be considered one of the largest brand content event in the world. It is an amazing way for brands to create emotional connections with their customers and the general public.

CO: Many of us outside Brazil have been watching your country with great interest as we read news stories of political and economic turmoil. (Outside the Olympics, of course!) I read with interest an article from the Guardian that you’d shared titled “The End of Capitalism.” Artists, of course, have a unique responsibility – that is, quite literally, the “ability to respond” – to social upheaval like that we are experiencing today. I guess my question is, how do you see the role of the musician in times of social unrest?

CC: I think that when artists manifest themselves politically they have the advantage of hearing. These are people who have more access to the public and it can make a difference in practical terms. The common people, especially in poor countries, are heavily influenced by artists. It is an important question of responsibility and should be considered.

The other big issue is related to the quality of political positioning. Not every artist thinks critically about politics. It should be, but is not. It is very common to see artists talking a lot of nonsense. Of course, there are the “privileged heads,” the artists who are very well prepared intellectually and politically. These figures can make an important difference in the course of history. If I’m not mistaken, this article you refer to “The End of Capitalism” came against what I was studying at the time. (It) deals with the shared economy, a subject that interests me especially. I do not think we are seeing the end of capitalism, but a transformation. It is no longer possible that in the twenty-first century, (there) still exists misery. This has to end quickly.

CO: Speaking of social unrest…Whenever I read your bio, the year of 1989 which you spent traveling the world is almost always mentioned. This must have been a very important year for you, and it certainly was important globally, as the Berlin Wall fell, and the cold war drew to an end. Do you want to talk some about how this year affected your growth as a musician?

CC: It was a very special year in my life and coincided with some very important events historically. In 1989 I was an itinerant musician, traveling for nine months throughout Europe. I had the luck and privilege of celebrating the Bicentenary of the French Revolution in Paris and witnessing first-hand the fall of the Berlin Wall. I was also in Budapest, near the Romanian Revolution, when the people overthrew the Communist regime of Nicolae Ceauşescu. I could feel the energy of transformation, but without the historical dimension that I have today. I was 21 and had been raised in a left-wing political environment. My father is a communist and was imprisoned and tortured during the dictatorship. I went to Berlin thinking to know the Eastern part. I was very curious to see firsthand how it worked a communist country. And I got to spend a whole day in the eastern part. Of course, it was very little time to form an opinion. But I remember that I felt the contrasting atmosphere, the simplicity of the people. Culturally, in just one day I could go to an amazing concert at the Berlin Staatskapelle and also bought an incredible amount of sheet music, something unimaginable in Brazil at that time. It was very striking and exciting.

A few days later I was surprised by my German friends who came home elated with the news of the fall of the wall. We went to the street and spent many hours in the crowd. A pity I could not speak German. I felt I was losing the details. But some things impressed me a lot to see. I remember it was very shocking to see long lines of East Germans enter the big brand stores such as BMW, Mercedes, or even sexy shops. It was very impressive. At that time West Berlin was stunning and shiny. The city shone. I had the feeling of seeing those pure people being contaminated by lust. It was really crazy!

CC: Thinking about it, that kind of transformation started with the change of the socialist paradigm may even be associated with this new model of capitalism in which rethinks the limits of profit, especially in terms of sustainability. We can not admit the misery nor admit the destruction of natural resources. Nowadays any revolution is possible because of technology. The connectivity already enables it. Ultimately we are talking about a social pact on important issues for everyone. No wonder that the great fortunes of the world are collaborating (regarding) key issues such as hunger and education. See Bill Gates and Warren Buffett. The Brazilian billionaire Jorge Paulo Lemann, richest man in the country, is revolutionizing education in the country. These are just a few examples.

CO: When many Americans think of Brazilian classical music, we might be limited to a few well-known figures, such as Villa-Lobos, or Laurindo Almeida. Who are we missing?

CC: We have an interesting musical history as the formation of a Brazilian musical identity, which could be defined as the synthesis between European, African and indigenous cultures. Villa-Lobos (1887-1959), is undoubtedly the great Brazilian composer of all time. (He) can be considered the inventor of a Brazilian sound. If the country has a unique sound, Villa-Lobos was responsible for it. The amazing thing is how his work is so little known, even here.

It is unfair to leave to point other very important composers, but I think for a first survey of Brazilian composers, I would highlight, in chronological order, composers with symphonic approach:

Carlos Gomes (1836-1896)

Henrique Oswald (1852-1931)

Alberto Nepomuceno (1864-1920)

Francisco Mignone (1897-1986)

Radamés Gnatalli (1906-1988)

Camargo Guarnieri (1907-1993)

César Guerra Peixe (1914-1993)

Hans Joachim Koellreutter (1915-2005)

Gilberto Mendes (1922-2016)

Willy Correia de Oliveira (1938)

Marlos Nobre (1939)

(And in) popular music:

Chiquinha Gozaga (1847-1935)

Ernesto Nazareth (1863-1934)

Pixinguinha (1897-1973)

Tom Jobim (1927-1994)

Laurindo Almeida, who made his career in the US, (was) part of our team of guitarists/composers who transited between choro and samba (bossa nova). Just name a few: João Pernambuco (1883-1947), Dilermando Reis (1916-1977), Garoto (1915-1945), Bola Sete (1923-1987), Baden Powell (1937-2000), Guinga (1950).

Which of course makes me want to ask – who were your primary influences, as a young musician?

At first, I was very influenced by my father’s musical universe. In spite of being a communist, (he) was a creative director in advertising and a poet. At home, we listened (to) jazz, classical music and Brazilian popular music (Tom Jobim, Chico Buarque, Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Milton Nascimento, Jacob’s Mandolin, Pixinguinha, Ernesto Nazareth).

I started studying classical guitar at the age of 10 and through college, I was very influenced by my main teachers of the instrument: Celia Trettel, Paulo Porto Alegre, and Edelton Gloeden. From a young age, I wanted to be a concert guitarist. My musical roots (were) very focused on interpretation, in the study of interpretation. In the search for refinement of sound, the articulation of voices (polyphony), understanding of the musical text: phrases, musical form, etc. I knew well the most significant repertoire for the instrument. I played and listened to many composers who are better known within the guitar universe. Just to name a few: Alonso Mudarra, Fernando Sor, Francisco Tárrega, and Leo Brouwer.

In addition to composers, I was greatly influenced by the great interpreters. At that time, I remember my idols were Julian Bream, John Williams, Manuel Barrueco, Assad Brothers and Brothers Abreu, for example. I heard very (many other) instrumentalists, like Glenn Gould, Jean-Pierre Rampal, James Galway, Nelson Freire, Martha Argerich, Daniel Barenboim, Mstislav Rostropovich. I could say that these were my musical roots.

— Camilo Carrara and Carolyn Ogburn

.

Carolyn Ogburn lives in the mountains of Western North Carolina where she takes on a variety of worldly topics from the quiet comfort of her porch. She’s a contributing writer for Numero Cinq and blogs for Ploughshares. A graduate of Oberlin Conservatory, UNC-Asheville, and UNC School of the Arts, she recently finished her MFA at Vermont College of Fine Arts and is currently seeking representation for her first novel.

.

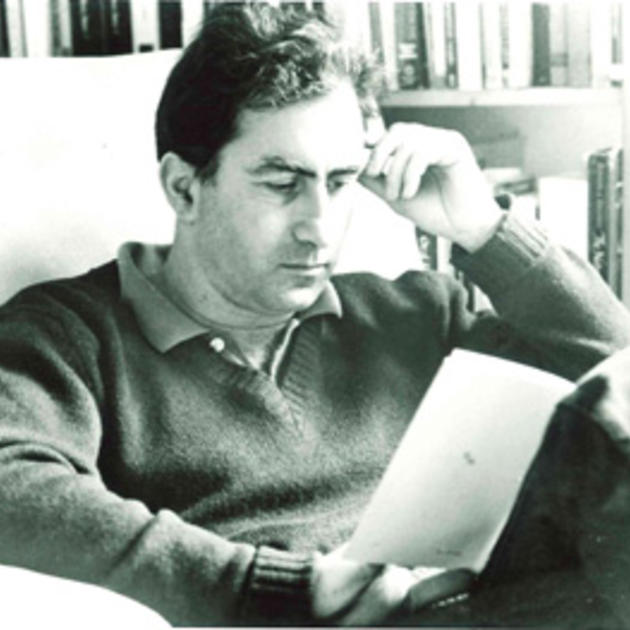

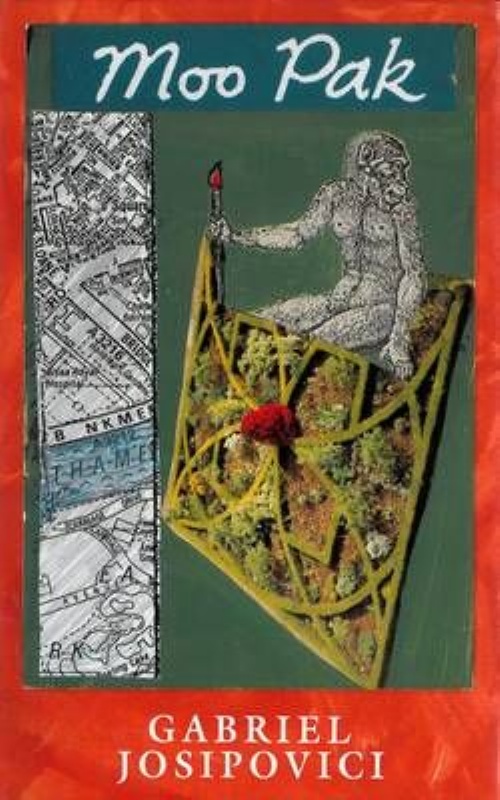

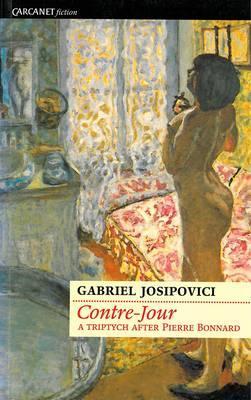

The first time I read Gabriel Josipovici, it was a slim, glossy brown volume sent to me by Carcanet that looked at first glance as if it might be poetry. It wasn’t, it was a short novel entitled Everything Passes, but I was struck by the amount of white space the reader is confronted with on each page, the writing being confined to a slender column of dialogue that is itself intermittent, fragmented by vertiginous silences. I began to read the first few words and felt myself slipping, slipping, as if down a polished chute, those aching blank spaces dragging me across to the next portion of dialogue as if across a dangerous precipice. I had to put it down for a while because it frightened me. And for the same reason I had to pick it up again. When it was finished, I was stunned. It was quite the most extraordinary piece of writing I had encountered in a long time.

Why has Gabriel Josipovici never won the Man Booker Prize? Or the Goldsmith’s, or the Costa Book Award? It’s a common question among those of us who are thrilled by his work. His reception by the British critical establishment has been a rocky one over the past 45 years, which remains perplexing to me. A man who spent his career teaching literature, a published academic critic and a writer of novels, short stories and plays of striking originality, should surely tick the right boxes? Maybe there is an otherness about his writing that stems from his childhood in Egypt[1] that lingers in his books just sufficiently to disturb the mainstream mind? Maybe he has been too far ahead of his time, and only now are we able to catch up with him?

Over the past few weeks, Gabriel and I have put this interview together over email. During this period he celebrated his 75th birthday and a strong sense of retrospection grew out of our conversation, a chance to look at the entirety of his writing life. I told him our focus would be on creativity: his creativity, the creativity in his texts, the creativity that his writing draws out of the reader. This was the result.

§

Victoria Best (VB): Let’s begin with The Inventory, your first novel published in 1968. I’d like to get a clearer picture in my mind of your mid-twenties self, a literary critic by now but embarking on a work of fiction. What was the inspiration for this novel?

Gabriel Josipovici (GJ): I wrote The Inventory before I wrote The World and the Book (1966, 1965-70). I had been writing fiction at least since my early teens – Monika Fludernik, when she was researching for her book on my fiction and drama, came to the house to look through my files and unearthed a short story I’d published in the Victoria College school magazine in 1954 in Cairo, when I was thirteen. It concerned a road waiting for the road-mender who comes every day to work on a stretch of it and who doesn’t come that day and will in fact never come again because he’s dead. I read it with amazement, because though it was naïve and didn’t really know what it was doing it had the voice I associate with my later writing, showing that this ‘voice’ is something one is born with, or that is the product of one’s earliest years, and, however ‘formative’ the experiences of one’s teens and later life, it remains constant. I went on writing stories, and in the year I had off between school and university I tried to write a novel but it was so bad and I believed in it so little that I burned it. But a story I wrote then was kept for ages by Encounter, the leading cultural journal of the time, who eventually wrote to say that after long consideration they’d decided not to publish it, but they’d like to see anything else I wrote, which was encouraging. Then at Oxford I wrote and published stories in University magazines, and an enterprising publisher (now an agent), Gillon Aitken, got in touch and asked to see more of my work. I was tremendously excited, of course, but it turned out he only wanted a novel. I said I didn’t have one but would naturally send it to him if and when I did. Despite this, I couldn’t seem to write anything longer than short (very short) stories.

I have often spoken about how I came to write The Inventory. It was such a breakthrough for me and emerged out of such turmoil and anxiety that – I now realise – it has acquired in my mind something of the status of a founding myth. But I’ve recently been reading through some of my early working notebooks and I can perhaps take this opportunity to round the picture out a bit, to release it (for myself at any rate) from its mythic dimensions.

After two years as a graduate student at Oxford and two as a young assistant lecturer at the University of Sussex, writing short stories no-one wanted to publish, I was getting more and more frustrated, feeling the need to write something longer than a short story, partly because I desperately wanted to have something substantial to work on for months rather than weeks at a time, and partly because I felt that if I didn’t write a novel I couldn’t really consider myself a proper writer (I had not yet read Borges or Robert Walser, who might have made me think differently), and partly of course because, as Gillon Aitken had shown me, publishers weren’t interested in short stories from unknown authors. I had even got to the point of feeling that much as I loved my work at Sussex, I would have to give it up, since I didn’t want to spend the rest of my days living the comfortable life of an academic but feeling deep down that I had betrayed the most intimate part of myself out of laziness or fear or for some other unfathomable reason. But the trouble was that, as I’ve said, much as I wanted to write something extended I found myself totally incapable of doing so. For if I worked out a plot I found it so boring to flesh out that the whole business of writing suddenly seemed meaningless, while if I didn’t have a plot the impetus petered out after a few pages.

A word had come into my head: inventory. Simply repeating the word to myself gave me gooseflesh. I realised that this was because the word seemed to pull in two totally opposed directions at once: in the direction of unfettered subjectivity, invention, and in the direction of absolute objectivity, an inventory list. I discovered that they actually derived from two different Latin words, invenire and inventarium, but that didn’t matter, there they both were, nestling inside the single English word. And suddenly I had a subject I was excited about: someone has died and the family, with the help of a solicitor, is making an inventory of the objects he (it soon became obvious to me it had to be a he) has left behind. As they do so the objects lead them into recollection or perhaps even invention of the person they had known and of their relationship to him.

But though I elaborated my basic plot I could not get the novel going. There seemed to be an insuperable gap between what I sketched out in my notebooks and any actual novel I might write.

I had a term of paid leave coming up at the end of my third year of teaching, and all through that year I pushed myself to write The Inventory (I knew my title) and all through that year I found I just could not get started. The three months I would have to myself (officially to write a critical book) grew and grew in importance. This was going to be the crunch. If I failed here I knew I would have to leave academic life for good and I had absolutely no idea what sort of job I would be able to get to keep myself and my mother – all I knew was that it would be a good deal less enjoyable and satisfying than the job I had. So, once the summer arrived, I knew there were no longer any excuses.

A beloved cat of mine had recently died and I decided, to take my mind off my anxiety, to write a children’s story about him. I had no children of my own but I did know and like very much a colleague’s three little girls, who had been very fond of my cat. So I imagined myself telling them his ‘story’. Day after day I simply sat down and wrote what I heard myself telling them. He had been a large neutered Tom, already an adult when we had got him, and when he sat out in the garden contemplating the world he looked rather like a triangle with soft edges. I called the story Mr.Isosceles the King.

The advantage of a children’s story was that I had no great expectations of myself and so no inhibitions to be overcome. I also had a clear audience in mind. And so I found myself, day after day, while on holiday in Italy, writing about Mr.Isosceles, until one day it was finished and I realised I had a book there which I had had no idea I would write and certainly no idea of the form it would take a month or two previously. So, as summer turned to autumn and autumn to winter, I had a new sense of confidence that just sitting and writing for a few hours every morning would yield something. Yet that did not allay my mounting sense of panic. I would wake up every morning drenched in sweat, my heart pounding. I knew it really was now or never. But fear, I discovered, can be a very useful thing. It can push one past all the inhibitions that have been holding one back and get one across that seemingly insurmountable barrier between notebook and novel.

VB: You’d already discovered the Modernist writers you loved and your relationship to them as a critic is clear. But what was your relationship to Modernism as a fledgling artist at this point? What did you hope to explore or elaborate in creative writing?

GB: The answer to the second question is: nothing. One writes because one has to, not to explore or elaborate anything. The answer to the first is, I suppose, that I had read Proust and Mann and Kafka, and Mann had made me understand that our modern situation is different from anything that has gone before, and fraught with difficulty; Kafka had made me understand that I was not alone in my sense of not belonging anywhere or having any tradition to call on; and Proust had given me the confidence to fail, had driven home to me the lesson that if you come up against a brick wall perhaps the way forward is to incorporate the wall and your effort to scale it into the work. I had read Robbe-Grillet and Marguerite Duras, and been excited by the way they reinvented the form of the novel to suit their purposes – everything is possible, they seemed to say. But when you start to write all that falls away. You are alone with the page and your violent urges, urges, which no amount of reading will teach you how to channel. ‘Zey srew me in ze vater and I had to svim,’ as Schoenberg is reported to have said. That is why I so hate creative writing courses – they teach you how to avoid brick walls, but I think hitting them allows you to discover what you and only you want to/can/must say. Not always of course. The artistic life is full of frustrations and failures as well as breakthroughs. You are alone. No-one can help you. I think that’s what Picasso means when he says that for Veronese it was simple: you mapped out the territory, started at one corner and worked forward. But for us, he says, the first brushstroke is also the last.

So: to go back to the genesis of The Inventory. I had my first scene in my head: the solicitor arrives at the house and meets the family of the deceased. I could visualise the street and the house. But how to put that down in words? Now I was sitting at the desk determined to write the book rather than simply thinking about it, this suddenly became a crucial issue. Did I use one sentence, one paragraph or one page to describe the scene? As I scribbled I found myself rejecting one effort after another: they were not in my voice, not what I wanted. They were in all the voices of all the novels I had ever read. How then to find how I wanted to say it? And suddenly, under pressure, the breakthrough occurred. I realised I was not interested in describing the scene, what I wanted was to get the characters talking to each other, to get the thing under way. And it came to me that I could simply drop all description and find ways of conveying the scene entirely through dialogue. With that the book became a challenge and a pleasure instead of a dutiful chore. I had my lists of possessions, my inventory, and I had my characters, and that was all I needed.

Years later I read Stravinsky’s account of a similar breakthrough he had experienced as a young composer (it was when working on Petrushka I think): ‘It was as though I had suddenly been given an extra joint in my fingers,’ he said. And years after too that I began to understand why I was so resistant to description, and why dialogue on the contrary seemed exciting. It was not description as such that I felt I simply could not (my body would not) do; it was that I could not countenance the introduction of an impersonal narrator who would be able to describe the scene from a privileged position outside space and time. It might seem that a first person narrator would solve the problem, but unless he was a sort of Tristram Shandy (and I found that much as I loved that book its wonderful playfulness was not something I was drawn to emulate) there would be exactly the same problem: in life things slip past us, we are always in the midst of them, we do not stop and describe, we simply take in our environment as we go. The traditional novel pretends to be doing that but in fact the first person narrator, when there is one, stands free of such pressures and simply tells the story. The descriptions he or she provides are meant to orient the reader, to act like stage directions. But I did not want such dead wood in my book. I wanted it to be alive from start to finish, from the first word to the last. And in dialogue it could be alive, for what dialogue did was provide words where (in the fiction) the characters would be providing words. Why the words are spoken, how speaking them affects the situation and what they ‘mean’ can be left as open as in any encounter in real life.

That was how, much later, I came to explain my peculiar aversion to description and my recourse, here and later, to dialogue. At the time I merely felt that I was embarked on an exciting journey and it was up to me to keep going till I got to the end.

VB: I’m also intrigued by your use of repetition – very strong in The Inventory, but also to be found in many other of your works. What is it about repetition, do you think, that brings us closer to the real?

GJ:I discovered, as I worked, that I could do without transitions. I could simply juxtapose fragments of dialogue and build up a rhythm in that way. Repetition was part of that process. As I soon discovered, Stravinsky worked in rather the same way. Instead of the development so central to the Western classical tradition he worked with small cells which he juxtaposed with others or transformed by various processes. And his descendants, I realised, were living and working in here England – Peter Maxwell Davies and Harrison Birtwistle, then young radicals setting out on their own paths, influenced by Stravinsky as well as by Varèse and Messiaen, but also harking back to late medieval and early Renaissance ways of building large works by other means than classical development. I spent many exciting hours at the concerts of the Pierrot Players, the Fires of London and the London Sinfonietta. And in the course of that discovered Stockhausen, Berio and Ligeti, very different composers, but all rejecting the linear, developmental processes of classical music and finding their inspiration in the musics of the Middle Ages, India and the Far East. It was an exciting time.

VB: What did the experience of writing this first novel teach you?

GJ: One other thing I discovered on the way was that under pressure of the situation all sorts of unexpected things occur. A writer I had not really thought about much, Raymond Queneau, became a great source of strength as I struggled with the book. Recalling his ability to maintain wild flights of fancy and yet hold on to ‘the real world’ of the France he knew, particularly in Zazie dans le métro, gave me the confidence to let go in ways I had never been able to do in my short fiction. It was frightening but exhilarating, a roller-coaster ride with no assurance that I would land on my feet at the other end. But, somehow, I did (I learned that if you let go you often do).

VB: How was it received?

GJ: Respectfully. I think it was possible to read it as a version of the English realist novel. And those were perhaps more open times, in the late sixties. Iris Murdoch’s first novel, Under the Net, was, after all, dedicated to Queneau and this was the time when John Berger and David Drew, Europeans to their core, were writing in the back pages of the weeklies. Critics only turned against me with my fourth novel, Migrations, which was a break from the predominantly dialogue novels I had been writing till that point.

VB: As a critic, how would you define the role of the reader?

GJ: I’ve no idea. Perhaps we should drop such notions as ‘the role of the reader’. Reading, as you know, is the most natural of activities. I’ve seen children who can’t yet read grab the book from their father’s hand and sit there, imitating him, turning the pages, willing themselves to read, as it were. I was fortunate to grow up in a pre-television and pre-computer age, so that there was nothing else to do if you were on your own except kick a ball around or draw or read. There came a moment when my mother put down the book she was reading to me to go and do something and I picked it up and went on with it. She came back and I handed the book to her to continue, but she only smiled and said she was busy and perhaps I could go on on my own. And of course I did. I wanted to find out what happened next. And I remember lying by the pool in the sports club in Maadi, near to Cairo, where I grew up, and looking up at the big clock on the wall and thinking: soon it’ll be time for lunch and after that I can go on with my book. And I felt a tingling in my whole body at the thought. I think the book in question was Enid Blyton’s The Castle of Adventure – I’ve never read anything more thrilling, though I’ve had many similar moments of looking forward to a blissful evening with a book I was absorbed in.

VB: I ask this because Migrations is an exemplary novel in the singular effect it has on me as a reader. Your narratives have such extraordinary elasticity; they open up new spaces in my mind. I find myself drawn to the trope of migration itself, and the way your characters often walk and talk, or walk and think; their movement echoes the mental travel I undertake reading you. Do you have such a figure as Iser’s ‘ideal reader’ in your own mind when you are writing? What do you think your novels ask of the reader?

GJ: I think one writes the books one would like to read but that no-one has written. So as you write you write for yourself as reader. That figure is not in your mind so much as in your body. He is not ideal at all, he is this person: you as reader of books.

But the first part of your question deserves a fuller answer. Quite a few years ago now I received a letter from a reader of my work who told me she had had M.E. [Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, the name previously used for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, though some argue the two illnesses are different] for many years, and for a long time no doctor would take her seriously, though she had fought hard to get her condition recognised (as of course it now is). She said reading my work had a physical effect on her, actually did what medicine and therapy could not do, that while she was reading my work she started to move better, to feel more like her old self. We corresponded and it turned out she was actually in a wheelchair, but clearly a very determined lady (in earlier life, she told me, when the disease was less virulent, she had acted and even taken a small company on a tour of Africa). She asked me if I thought she should do a PhD on my work, and tried to get in to various universities to do that, but for one reason or another it didn’t work out. I suggested to her that PhDs were probably not a good idea in the Humanities (a view I hold generally), and that if she felt driven to write about my work she should just do so. Over the course of the next years she did that and in the end had a substantial book. I read it with interest because I had always been fascinated by the kind of thing Oliver Sacks was doing and loved the idea that books could have a physically, not just emotionally or intellectually, restorative effect on the reader, not just on the writer. I had hoped that in the wake of Sacks’s popularity a publisher might be persuaded to publish her book, but alas no-one would and I remain one of its sole readers. But I cherish my copy as a witness to the effect art can have.

I don’t think there’s anything uniquely ‘restorative’ about my work; if she had happened to read someone else I’m sure that would also have done the trick. Not anyone else, but I have certainly found that the authors I warm to affect my body and not just my mind. And in essays and books like Writing and the Body I’ve tried to explore in an amateur way why that should be the case. But while neurologists have been (rightly) alert to the therapeutic effects of music, and even painting, poetry and fiction have not in the past been examined from the same perspective. This has, though, recently become a topic of research, and Terence Cave, for example, has devoted some of the money he received from his Balzan prize to setting up a team in Norway to look into it, while Paul Davis and a team at Liverpool are engaged in the same enterprise. Both of them though seem to me overly scientific and abstracting. I just wish the topic would find its Oliver Sacks.

As for Migrations and migration, that work was indeed another breakthrough for me. I had grown to feel that the dialogue form I had developed in The Inventory and which I had adopted for my next two novels, Words and The Present, was no longer satisfying. I had had a few plays publicly performed and been made welcome in the wonderful BBC Third Programme and the Radio Drama department, presided over by Martin Esslin, and full of great producers able to call on the best actors in the land. My play Playback, which I worked on with that great producer, Guy Vaesen, kicked off a season of radio plays exploring the possibilities of the form. I felt more at ease in my teaching role at Sussex now it was established that part of my time at least would be spent writing. Yet in personal terms 1972-5 were very difficult years for me. A good friend committed suicide. My beloved collie dog, who had developed epilepsy in a very violent form, grand mal rather than petit mal, with fits lasting all of 36 hours, had finally had to be put down, and I could not get out of my head the look in his eyes as he felt a fit coming upon him and with no idea, of course, as a human being would have, of what was about to engulf him. I had behaved very badly to a number of people who were very close to me. All I wanted to do was beat my head against the wall and scream. In those circumstances the lightness and humour of my early novels did not seem to be of any help. I wanted to be engaged in something that went deep and that (as I put it to myself) wound round and round and round, and in the writing of which somehow the shackles I felt were binding me tight might get released. I felt I needed to go down into my own life, but when I did so I found I had no ground to build on – I had no maternal country to dream about, not even a maternal language. I felt I was a sort of absolute migrant – someone on the move from my birth on, with no place to return to and no place to go to. How, in that condition, to find any solid base on which to stand to build something substantial? Yet as I thought about all this I began to wonder if perhaps my condition was more typical of the human condition at large than our culture (any culture?) was willing to recognise. Most people have a patria and a maternal language and the notion that these are primal is somehow unquestionable. But is it true? Or is it perhaps just another myth. Perhaps if one dug down deep enough one would find only shifting sands. I started to read quite a lot of French psychoanalysis (my close friend John Mepham was a great resource there), and in particular André Green. And I began to feel that perhaps I could find a fictional form for all this.

Two images came into my mind under the pressure of trying to find my form: a Francis Bacon image of a man vomiting into a lavatory, bent double over it, a painting I must have recently seen; and Epstein’s great sculpture of Lazarus rising, the shrouds that had been wrapped about his body starting to come loose, which I had discovered in New College chapel when I was a student down the road at St.Edmund Hall and which I often used to go and contemplate in my time at Oxford. I was also listening to the current work of Peter Maxwell Davies, those enormously slow, enormously long works audiences at the time were walking out of, like Worldes Blis and the Second Fantasia on John Taverner’s In Nomine, which developed almost imperceptibly, like their great late medieval models, from tiny cells to monumental structures. And then I heard Harrison Birtwistle’s The Triumph of Time, and I knew I had to write my book. It knocked me backwards, that long long slow ritual on strings and percussion, punctuated by the piercing, beautiful descant of the clarinet. Towards the end of the huge single movement there is a glimpse of something found, then that too is swallowed up in the funereal march. Finally, I was just starting to learn biblical Hebrew in order to read the Hebrew Bible in the original language. I was also reading the Bible in English quite intensively. I came across this phrase in the prophet Micah: ‘Arise and go, for this is not your rest.’ (Micah 2.10) I loved the sound of it in Hebrew: c’mu velochu ki lo zot ha-menuchah, and I was excited to discover that the word for rest, menuchah, is also to be found in various other places in the Bible, notably when the dove is sent out of the ark by Noah but can find no rest for her feet because the earth is still covered by water. I knew then that I had found the epigraph to my book, and, after much internal debate, decided to leave it in Hebrew to give a sense of its otherness and strangeness, and since the precise reference would allow anyone interested to look it up in an English Bible.

I had been driving up and down the road that leads from Brixton to New Cross, a road that filled me with horror every time I took it, it was so endless, so run down and desperate (it must have changed dramatically, like all of London, in the forty years since I was there), and I took that as my location. I hoped that by facing that despair and the despair of the man in Bacon’s sealed room vomiting into the lavatory, by finding a way of writing it, I might regain a modicum of balance. But I was terrified that so instinctive a procedure would lead to nothing more than a mess, so that though I wrote it straight, day after day, never looking back, once that first draft was done I subjected it to more analysis and drew more grids than I have ever done before or ever want to do again. I found that the pattern 9+1 was a recurrent one, tweaked it here and there, and decided on a title with nine letters plus the sign for the plural. And so Migrations was completed.

I had been so deeply immersed in it, and it had seen me through such a bad time, that, once my only reliable reader (relied upon to criticise as well as praise, which is essential), my mother, had read it and said she was deeply moved, I felt happy to send it to Gollancz, who had published my previous three books, including my first volume of short stories, Mobius the Stripper: Stories and Short Plays. That volume had been awarded the Somerset Maugham Prize, a wonderful accolade for a young writer, news I had received on returning from a brief holiday to try and come to terms with my friend’s suicide, but at the last minute the prize was withdrawn on a technicality (I had not had an English passport when I was born, a fact I had never tried to hide, but which it seemed was a stipulation by Maugham for the award of the prize, even though in his lifetime he had waived that requirement in a couple of instances, and which the publishers, who submitted the book, had overlooked) and Gollancz, who had slipped bright yellow wrappers announcing the award on all copies of The Present, which they were about to publish, had to hurriedly remove these. Insult was added to injury when the chair of the Society of Authors, which managed the prize, Antonia Fraser, wrote more or less accusing me of deliberate fraud and ended with the chilling words: ‘However, I am sure you will agree that the publicity you are getting more than makes up for the withdrawal of the prize.’ Be that as it may, Gollancz took one look at Migrations and turned it down. When it was eventually published it was rubbished by the critics, Susan Hill, for example, saying (was it in The Observer?) ‘If you like that sort of thing then that is the sort of thing you will like.’ It was my first encounter with the entrenched conservatism of the English media and especially of established English writers, a conservatism I now suspect (after the similar outburst of bile that greeted my recent critical book, What Ever Happened to Modernism?) is due more to anxiety than to anything else.

VB: The other figure that recurs across your works is the figure of the man alone in his room. This makes me think of both the reader and the writer, who are often in such a situation. What draws you to this figure, or perhaps better to ask, how was this figure thrust upon you?

GJ: I think I’ve answered this in relation to Migrations. As for its larger or deeper significance, all I can say is that my pulse quickens when I see paintings or listen to music or read books where the constraints are fairly tight – where a room hems in the figures, as in Vermeer or Hammershøi or some of Giacometti, or the musical resources are limited, as in Renard and Histoire du soldat. Why it should do so is a difficult question, better left to others.

VB: I wonder if we might bring in your notion of art-as-toy here; something material and real in its own right but invested with imagination and fantasy. Do you think, as both author and critic, that the ‘toy’ of art is different – invites different kinds of play – for its creator than for its consumer?

GJ: Not sure I understand this. Art is making, poiesis, and what I like about much modern art is that it acknowledges this, indeed, makes a virtue out of it. We may be nostalgic for the organic, for art growing as a tree grows, but to accept that art is made by someone at some moment is exhilarating for me. That’s why I love Tristram Shandy. Of course there are dangers. If one starts to think of it as simply artificial one is set firmly on the conceptual route, and though I am interested in Duchamp, who was a complicated and conflicted figure, I am not much interested in his followers. A key moment in What Ever Happened to Modernism?, to my mind, though no-one has mentioned it, is the confrontation I set up between Duchamp and Bacon. Both of them want nothing to do with mere description, nor do they want to go down the road of abstraction, but where Duchamp views every artistic gesture with suspicion, Bacon is prepared to trust the moment, to trust his painterly gesture. Duchamp has all the philosophical answers, but Bacon is a bit like Dr.Johnson confronting Bishop Berkeley: he kicks the stone. Duchamp will never be accused of self-indulgence or losing the plot, but my heart is with Bacon. And more than my heart. I believe that if we realise that a child lives the toy, lives with the toy, while never for a moment thinking it is anything other than a toy, then we perhaps have a better model of our relationship to art than the conceptual one. I at any rate dream of making a work that is like some complicated toy you can dismantle and put together again and that is always not just more than the sum of its parts but in a different dimension. So I love works like Perec’s La vie mode d’emploi or Birtwistle’s Carmen Arcadiae Mechanicae Perpetuum and Steve Reich’s percussion pieces – but of course I also love works which are not like that at all, such as those of Kafka and Beckett and Stockhausen and Kurtág.

VB: Perhaps we might address the influence of Jewish elements in your works. It would be foolishly reductive to call you a ‘Jewish writer’; yet patterns of migration and exile are evocative, and many of your protagonists identify themselves as Jews (in a way that is often serious and amusing at once). How would you describe these elements in your writing?