To think that this horde of precious and irreplaceable books was sitting in the woods less than 2 hours away from my home in New England sends chills down my spine. —Melissa Considine Beck

American Philosophy: A Love Story

John Kaag

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2016

272 pages; $26.00

O Wild West Wood, thou breath of Autumn’s being.

Thou, from those unseen presence the leaves dead

Are driven like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing.

Yellow, and black, and pale, and hectic red,

Pestilence-stricken multitudes: O thou

Who chariotest to their dark wintry bed.

—“Ode to the West Wind,” Percy Shelley

.

Holden Chapel, at first glance, is a small, unassuming, forty-foot, Georgian style, brick building on the campus of Harvard University. But it has a rich and interesting history as the third oldest building at Harvard and as one of the oldest college buildings in America. In December of 1741, Harvard accepted a generous donation of 400 pounds sterling from Mrs. Holden, widow of Samuel Holden, and her daughters to build a chapel on campus. The building was erected in 1744 and from that year until 1772 morning and even prayers were held for students in the quaint building and it also served as a place for intimate and engaging lectures. On April 15th, 1895 the American Philosopher William James delivered his famous “Is Life Worth Living?” essay to a group of young men from the Harvard YMCA.

William James, known as the Father of American Psychology, was the son of Henry James, Sr., the Swedenborgian theologian, and the brother of the famous American novelist Henry James. William James contemplated becoming an artist, but in 1861 he enrolled in medical school at Harvard where he eventually graduated with an MD. But James never practiced medicine and was instead drawn to psychology and philosophy and became a pioneer in both of these fields. During his young adulthood James suffered from long bouts of depression which were diagnosed at the time as neurasthenia. His depression and anxiety, which he calls his “soul-sickness” led him to contemplate suicide and he even overdosed on chloral hydrate in the 1870’s just to see how close he could come to death without actually crossing that threshold. It was the exploration of philosophy and his attempt to answer the question “Is Life Worth Living” that brings him out of his malaise and inspires him to compose some of the most important philosophical pieces that make up the American school of pragmatic philosophy.

John Kaag’s philosophical and literary memoir American Philosophy: A Love Story, begins with the young philosopher’s own “soul-sickness” and his frequent visits to the site of James’s famous lecture, Holden Chapel, in the Spring of 2008. Kaag is on a postdoc at The American Academy of Arts and Sciences when his crumbling marriage, the death of his alcoholic father and the stagnation of his research push him to contemplate what he believes to be William James’s most important philosophical question: “Is Life Worth Living?”

I was supposed to be writing on the confluence of eighteen century German idealism and American Pragmatism. Things were progressing, albeit very slowly.

But then, on an evening in the Spring of 2008 I gave up. Abandoning the research had nothing to do with the work itself and everything to do with the sense that it, along with everything else in my life, couldn’t possibly matter. For the rest of my year at Harvard I assiduously avoided its libraries. I avoided my wife, my family, my friends. When I came to the university at all I went only to Holden Chapel. I walked past it, sat next to it, read against it, lunched near it, sneaked into it when I could—became obsessed with it. James had, as far as I was concerned, asked the only question that really mattered. Is life worth living? I couldn’t shake it and I couldn’t answer it.

Kaag’s clipped and pithy sentences which employ asyndeton for maximum dramatic effect make this book about so much more than philosophy and literature. He is not afraid to reveal his darkest thoughts or lowest moments and he is also not above using profanity or embarrassing stories about himself to get his point across. The style of deep, private reflection mixed with philosophical dialogue is reminiscent of Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. But, unlike Pirsig, who wrote computer manuals for a living, Kaag’s book is a great personal and professional risk for a philosopher whose two previous books are for a very specific, academic, Ivory Tower audience: Thinking Through the Imagination: Aesthetics in Human Cognition and Idealism, Pragmatism, and Feminism: The Philosophy of Ella Lyman Cabot.

Holden Chapel, Harvard University

Holden Chapel, Harvard University

American Philosophy is aptly and cleverly divided into three main parts which recall the journey in Dante’s Divine Comedy: Hell, Purgatory and Redemption. Kaag’s journey starts in Part I, in “Hell,” on his way to the White Mountains in New Hampshire for a philosophy conference on William James at the Chocorua Public Library, but he gets sidetracked for the first of many times throughout the book. There is a sense of wandering and loneliness that punctuates American Philosophy and in this instance, the first real instance of meandering, Kaag can’t even bring himself to his end point which is a professional conference. Instead of going to meet his colleagues at the Chocorua Library, he stops at a German bakery where he meets Bunn Nickerson. This kind, ninety-three-year old, local gentleman tells Kaag that William Ernest Hocking, the prominent 20th century American philosophy professor from Harvard, has an estate which is nearby and contains a unique library. Bunn offers to take Kaag there to have a look around.

The family still used the Hocking estate, which was named West Wood, in the summer, but in the fall of 2008 all of the buildings were empty of any human inhabitants and the library appeared to be utterly neglected and abandoned. A copy of The Century Dictionary from 1889, a first edition encyclopedic dictionary with more than seven thousand pages and ten-thousand wood engraved illustrations, catches his eye through the window and his decision to enter this library, even though it was trespassing, completely alters the course of Kaag’s life for the better.

Kaag stumbles upon an opportunity to heal his soul in the form of West Wood’s stone library which, upon entering, he discovers is home to more than 10,000 books. The books that Kaag finds inside this unlocked and unheated building, especially the number of first editions, are the stuff of dreams for any bibliophile. Among the rodent droppings, porcupines, termites, various other bugs and dust Kaag finds Descartes’ Discourse on Method–first edition from 1649, Thomas Hobbes’s Levithan-first edition from 1651, the complete, leather-bound volumes of the Journal of Speculative Philosophy, John Locke’s Two Treatise on Government from 1690, Kant’s Kritik der reinen Vernunft from 1781, Emerson’s Letters and Social Aims–first edition, 1875 and on and on. To think that this horde of precious and irreplaceable books was sitting in the woods less than 2 hours away from my home in New England sends chills down my spine.

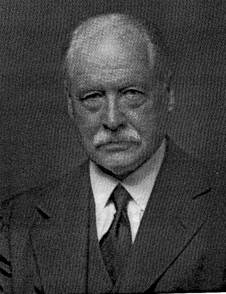

William Ernest Hocking, the owner of this vast personal library was, like his teacher William James, also a pragmatist who believed that philosophy could have an effect on real life. His personal library was a collection of not only European thinkers and philosophers, but he also amassed books that contained the thoughts of Eastern philosophy. Hocking studied with James at Harvard as well as other American thinkers such as Royce, Palmer and Santayana. In 1908, Hocking moved from his home on the West Coast to accept a teaching position at Yale and in 1916 when his mentor, Josiah Royce died, Hocking took over his chair in philosophy at Harvard. Hocking would go on to spend the next forty years at Harvard making a name for himself as one of the prominent scholars of American pragmatism. Kaag discovers that many of the books in Hocking’s library were once owned by Hocking’s famous teachers and colleagues at Harvard and some of their signatures, notations and inscriptions inside the books were just as valuable as the leather bound books themselves.

Throughout the course of Part I, Kaag’s “Hell,” he comes to the painful decision that his marriage is a mess and not capable of being saved. He leaves his wife in Boston and spends more and more time at West Wind where he becomes acquainted with Hocking’s granddaughters, Jennifer, Jill and Penny. The sisters are “surprised and releived” that someone is interested in the books and Kaag begins to catalog the massive collection and attempts to save the oldest, most vulnerable books by moving them to dry storage. As he works his way through the books he continues on his deeply personal and lonely struggle with his own purpose and existence. He writes:

In the following months I started cheating on my wife with a room full of books. I made the trip to New Hampshire repeatedly. My wife and mother—in a unison that always infuriated me—demanded to know where I was going. I could have told the truth but instead I chose to lie, making up conferences that needed to be attended and friends I wanted to visit. Up until that point my life had been so routine, so scripted, so normal, so good—but my brief encounter with my dead father the previous year had brought that life to an unceremonious end. Nothing about life is normal. And nothing about life has to be good. It’s completely up to the liver. The question—Is life worth living?—doesn’t have a scripted, public answer. Each answer is excruciatingly personal, and therefore, I thought, private.

One of the greatest strengths of Kaag’s narrative is that he is not afraid to show that his attempt to escape his wretched existence by means of the library at West Wind was not always noble or dignified or pretty. He skips meals, he neglects his hygiene, he drinks excessively, he begins to prematurely age and he sleeps out in the woods behind West Wind where he catches a nasty case of Lyme Disease. Who among us hasn’t hit a low point in our lives to which we can look back and trace our gradual ascent out of the abyss? The stark honesty of Kaag’s narrative is brave, especially for someone who is an academic philosopher, because he includes all of the ugliness of his journey from Hell to Redemption which details he could have just as easily skimmed over or avoided altogether.

The ideas and themes of American philosophy and literature which are unfolded within the pages of Kaag’s book mimic the philosophers own process of discovery as he unpacks and unfolds the wonders of Hocking’s library. One encounters James, Emerson, Thoreau, Coleridge, Camus, Royce, Whitman, Peirce, Frost and Dante just to name a few. Many readers never give much thought to American philosophers, or as Kaag notes, American philosophy is regarded as “provincial” and “narrow in its focus.” Kaag, however, delves into the pages of American philosophical writings with unbridled enthusiasm that is enhanced by his literary ability to tell interesting and engaging stories about the real lives of these great American thinkers. As one example of this, Kaag summarizes the philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce’s struggle with the idea of freedom and the impact chance has on our choices. Peirce took issue with the emphasis of orderly design over chance and freedom that Darwin and the evolutionists promoted. The philosophical theories of Peirce’s Design and Chance are discussed by Kaag in the context of Peirce’s struggle in his personal life with romantic love. The anecdotes and stories about Peirce’s real life struggles makes what could be a dry recounting of Peirce’s philosophical pragmatism into a gripping story about a great thinker who is attempting to make sense out of his confusing and chaotic world.

Kaag spends the next year in the woods at West Wood with Hocking’s books and continues to contemplate James’s important question. As he works his way through the library he reads countless volumes of American philosophy and literature, with a few Europeans mixed in, that help him through the different stages of his emotional and spiritual journey. The most significant turning point in Kaag’s Hell is when he begins reading Thoreau and reflecting on that writer’s own retreat to the woods. Kaag becomes frustrated with Emerson’s idea of self-reliance which he feels is unattainable and unrealistic. Instead he embraces Thoreau’s example of simplicity, cultivating the earth, and turning off and tuning out all of the modern amenities that distract us from searching for real meaning in our lives.

At one point Kaag takes a break from sifting through books in the library asks Hocking’s granddaughter, Jennifer, the least “intellectual” of the sisters, if he can help her clear a field by scything. As he takes in the simplicity of the landscape at West Wood and tries to deal with this very physical task, Kaag comes to realize through this experience of scything that the process of self-discovery needs to happen for him outside of the walls of the stone library and that this process would be slow and couldn’t be forced; he learns to stop and look around him and be mindful of his surroundings and this becomes his first, significant step from Hell to Purgatory.

In Kaag’s Purgatory, the subtitle of “A Love Story” is further explained through the first glimpses and descriptions of Carol whom the author confesses he should, by all accounts, have hated. By this point in the book he is divorced and his ex-wife is remarried and moving out west, but Kaag’s loneliness and isolation linger. He continues to spend hours and days and weeks at West Wind and to catalogue Hocking’s library and to save the most precious volumes from the elements. One weekend he invites Carol, a colleague of his from UMass Lowell, a Kantian feminist, who is also his rival for a tenure track academic job, to join him in sifting through the library at West Wood. Carol is married, but her husband lives in Canada so their long distance relationship gives her plenty of freedom and independence to travel with Kaag to New Hampshire on this as well as many occasions.

While sifting through the pages of Hocking’s library and taking hikes through the White Mountains together, it is evident that Kaag’s feelings for Carol become more than friendly. There is a hint in the text that Kaag, in the tradition of Dante, wants to find his inspiration, his Beatrice and he has found just such a companion in Carol. But her marriage and his general uncertainty about the direction of his life makes for an unexpected element of suspense in the midst of the book as he debates how or when he should reveal his true affections for her. Thoughts of American philosophy and James run through his mind as he is mulling over his decisions:

Shall I profess my love? Shall I be moral? Shall I live? These are the most important questions of modern life, but are also questions that do not have factually verifiable answers. For James such answers will be, at best, provisional. There are no physical signs that one is emotionally ready to become a lover or husband, auguries that suggest one will be any good at any of it. In fact, there is often a disturbing amount of countervailing evidence. But human beings still have to choose, to make significant decisions in the face of uncertainty. Love is what James would have called a “forced option”—you either choose to love or you don’t. There is no middle ground.

Kaag deliberately chooses to exclude the details of his development of an intimate relationship with Carol. The decision to keep this part of his personal life between himself and Carol is worthy of great admiration and respect—he knows that an author can cross the threshold into the type of salacious writing that is meant to sell books and Kaag stops just shy of veering into the realm of romance. Kaag simply remarks about their decision to choose love and to choose one another: “Some things are better left unsaid, and others can’t be said at all.”

But we do get a glimpse of their life together in the final part of American Philosophy which has the hopeful title of “Redemption.” Kaag finds happiness, true love and companionship and Hocking’s books find a safe haven in the library at UMass Lowell. But despite the happy ending for all persons and things involved in his journey, Kaag is still all too aware of the ephemeral nature of our existence and he acknowledges that we are responsible for making our own meaning in life with what we are given.

Kaag concludes with a reflection of his time at West Wood and how far he has come from those lonely days in 2008 when he was obsessed with Holden Chapel. In 1780 religious services ceased to be held in Holden Chapel and in 1800 it was converted into a chemistry and dissection lab for the students of Harvard medical school. Bones that were the remains of medical dissections were discovered in the walls of the chapel when it was renovated in 1990. Nowadays Holden Chapel reverberates with the sweets sounds of music as it is used by the Harvard Glee Club for practice. Kaag notes that in the Middle Ages it was not uncommon to bury the bones of the dead in buildings for apotropaic purposes but also because they were good for the acoustics. This strange mix of the sounds of the living occupying the same space as the bones of the dead in this small, historical chapel is reminiscent of the opening lines of Yves Bonnefoy’s Ursa Major:

What’s that noise?

I didn’t hear anything….

You must have! That rumbling. As if a train had roared

through the cellar.

We don’t have a cellar.

Or the walls.

But they’re so thick! And packed so hard by so many

centuries…

—Melissa Considine Beck

N5

Melissa Beck has a B.A. and an M.A. in Classics. She also completed most of a Ph.D. in Classics for which her specialty was Seneca, Stoicism and Roman Tragedy. But she stopped writing her dissertation after the first chapter so she could live the life of wealth and prestige by teaching Latin and Ancient Greek to students at Woodstock Academy in Northeastern Connecticut. She now uses the copious amounts of money that she has earned as a teacher over the course of the past eighteen years to buy books for which she writes reviews on her website The Book Binder’s Daughter. Her reviews have also appeared in World Literature Today and The Portland Book Review. She has an essay on the nature of the soul forthcoming in the 2017 Seagull Books catalog and has contributed an essay about Epicureanism to the anthology Rush and Philosophy.

.

.

Thank you for this review!