Photo by Tain Gregory

Photo by Tain Gregory

Sophfronia Scott offers here a thoughtful, provocative and pragmatic account of the ways a nonfiction writer can use reflection to engage the reader. She talks specifically about the use of techniques such as metaphor, direct appeal, shared experience and the right voice to engage the reader’s heart and imagination. Especially helpful are Scott’s explorations of particular texts to illustrate her technical points: Elie Wiesel’s Night, Eula Biss’s Notes from No Man’s Land, and James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son.

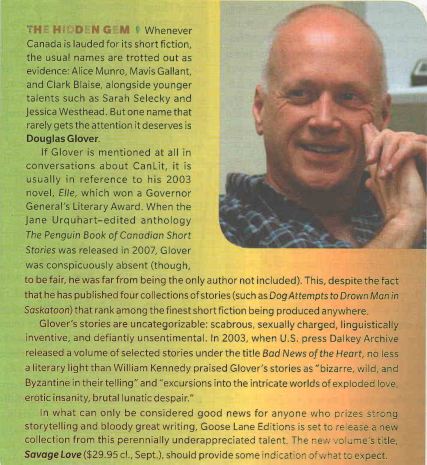

dg

———

Introduction

In the past I rarely embarked on a personal essay unless specifically asked for one by an editor because it never immediately occurred to me anyone would have any interest in what I had to say about a particular topic, especially if the action involved happened only to me. I have also had a distaste for the trend towards memoir in the publishing world. When the writer Douglas Goetsch, a recent graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts, said to me in conversation that he thought the United States was suffering “from an epidemic of memoir,” I, having read my share of melodramatic manuscripts flooding the marketplace in recent years, was inclined to agree. There are, it seems, millions of keyboards where writers are too enthusiastically tapping out their tales of child abuse, alcohol abuse, road trips, adoption secrets, illness, injury, divorce, you name it. I saw no reason to add my words to this particular multitude.

However in August 2012 I found myself deeply engaged in the writing of a personal essay inspired by a series of tweets I had posted to a friend on Twitter describing a talk I’d had with the singer Lena Horne about learning to iron my father’s shirts. The previous day I had been ironing my husband’s shirts and I posted on Twitter:

I’m going to combine my housework with my literary love and pretend I’m a Tillie Olsen character: I stand here ironing…

The next morning I saw my friend had re-tweeted the post and as I tweeted my thanks for some reason the memory of my Lena Horne talk came to mind. I wanted to tell my friend about it; he enjoys a good story and I thought he would appreciate it, especially since it included a celebrity. I sent the following in quick succession:

1.) Thanks for the RT! I once had a conversation with Lena Horne about ironing—we both learned as girls…

2.) …She said she could never get it right. “I used to weep over my daddy’s shirts.” I said, “And they were all white shirts,

3.) …right?” My father’s shirts were all white too. She said yes. I was in my 30s. She was in her 80s. But we walked through…

4.) …Central Park together as girls ironing our father’s shirts.

5.) I’m in tears now remembering that day.

And I really was in tears. I embarked on the writing of an essay with no ambition other than to explore the source of those tears. This walk with Lena Horne was still in my heart and at the forefront of my mind over ten years later for a reason and, as I discovered as I wrote, those reasons had little to do with her. As the paragraphs of the essay came together I realized that walk had crystallized an important personal moment for me in which I recognized how much love and forgiveness had replaced the anger I once held for my difficult, demanding father.

“Such forgiveness is possible, I believe, not because he is long dead, but because of these unexpected moments of grace reaching across generations reminding me of this: the reason I hurt so much then was because I cared so much then—and still do. As I look back on that autumn afternoon and how Lena took my arm again as we continued our stroll through Central Park, I can see how in that moment I was in my 30s, Lena was in her 80s, but we were both girls ironing the shirts of the first men we ever cared for, and hoping they could feel our love pressed hard into every crease.”

The completed essay, “White Shirts,” when published in the September 2012 issue of Numéro Cinq Magazine, received favorable written responses. What surprised me about the posted comments was how many of the readers saw themselves and their own memories in my essay:

I recall my Aunt Virginia showing me how to iron a shirt when she was doing them for her husband and family of 5 boys after a morning of working in the fields. Yours are exactly the same instructions I recall her demonstrating. Thanks for sharing this evocative memory.

You’ve taken me back to my childhood, ironing the handkerchiefs and pillowcases while I watched my mother and grandmother iron starched white shirts. Thank you.

This is precious, pulls you into the story, and encouraging to me as a young housewife finding I have grossly undercooked the potatoes in a casserole, and realizing just how quickly a cleaned bathroom collects new hair and dirt- I can get better!

This brings back my own ironing memories. My grandmother, who would be 120 if she were still alive, taught me how to iron. I don’t remember what she had me iron, but I do remember burning my fingers. If I look hard enough, I can still see the tiny scars.

This excited me as a writer—it was as though the essay had become bigger, more vital, because it had struck a chord for so many people. We were all, at once, at the ironing board with our mothers, aunts and grandmothers. I found myself thinking, if this is what creative nonfiction can do, this is the creative nonfiction I want to continue writing.

But how? I felt I had created this shared experience, a kind of universal appeal, by accident. I know the best essayists must be able to make such connections consistently. I decided to begin an exploration of the techniques these writers use to help them communicate their very personal experiences to the broadest possible audience. I believe this is a necessary exploration because, as Richard Todd says in Good Prose: The Art of Nonfiction, “In the family of writers, essayists play poor cousins to writers of fiction or narrative nonfiction.” Indeed their medium, the personal essay, is an unusual form because its existence defies the fact that the reader, at first blush, has no reason to read it. What is the essay’s purpose? Fiction offers entertainment as an essay can, but on a different level: fiction can also present escape, perhaps even a fantasy in which the reader can place him or herself as the main character. Journalistic nonfiction serves the purpose of educating the reader or providing desired information. Poetry can charm with its rhythms and imagery. These forms answer upfront the reader’s ongoing question of “What’s in it for me?” In a society where words and phrases such as “So what?” and “navel-gazing” and “whatever” demonstrate a less than supportive environment in which to offer one’s story, the essay is immediately at a disadvantage. In everyday conversation we don’t always listen to the stories of strangers, or if we do it’s done with half an ear because the listener is more interested in hearing a moment where they can interject what they have to say, which they believe will be more interesting or more important. Douglas Glover, in his book Attack of the Copula Spiders, warns against “bathtub” narratives which he defines as “a story which takes place almost completely as backfill in the mind of a single character (who often spends the whole narrative sitting in a bathtub—I am only being slightly facetious).” He notes the form for its lack of drama and movement. But what is a personal essay if not a long form “bathtub” narrative completely crafted from the writer’s thoughts being turned over and over in her mind?

Since I’ve been able to focus on creative nonfiction in my studies, I’m learning this type of focused reflection is not the problem with the personal essay. I realize the essays and memoirs that bother me the most are ones where deep thought and reflection are nonexistent. On top of this the author has not taken the pains to write in a way that would allow the reader access to her personal experience. The writer, either through neglect or inexperience, has produced a work in which she is so caught up in telling her story, usually a traumatic event, that she has not made the thoughtful reflection required to instill the event with meaning. It’s not enough that a person has experienced something horrible such as the death of a loved one, physical abuse, divorce or illness. The person must be able to step back and look at the whole tapestry and contemplate the placement of the event and its effects on her whole being. Once that piece is understood, this gives the writer the foundation to craft and revise a piece with the intention of highlighting this insight.

In many cases the writer has not stepped back at all. Such writers are, in my opinion, still caught up in the event, even if many years have passed. For them writing down the story is the big accomplishment, and that’s because the pain of finding the words has them reliving the event and “surviving” it again. They are too much in it to be above it, so there is no reflection. Thus the event is still too personal for the writer and hence out of reach for the reader. If anything this type of writing does a certain violence to the reader because it subjects them to raw, naked details very similar to a news report from a crime scene. We, as readers, endure the pain, the harsh visuals, and the terror of the event. Then the author thinks it is enough just to explain they got through it, and they’re okay. But how can we believe that when we’re still ourselves in that place of fear and trembling, exactly where they left us?

And yet there are essays and books of essays describing terrible events that, despite their personal nature, manage to capture the reader’s heart and imagination, engaging both the ear and the heart. In order to gain such credibility with the reader a writer’s work should demonstrate that the author has done some focused thinking, first about herself, and then for the reader. For herself the writer wants to do the mental work and reflection that shows she is ready to discover and understand the deeper meaning of the events of her life—to take the step that truly turns life into art. Next, the writer makes choices with the reader in mind—choices of imagery, language and voice with the intent of making a connection with the person reading the words. I will detail here how this process can work using as examples authors who have written engaging, yet deeply personally essays that succeed because the writers have brought to bear the powers of both inner work and conscious attention to craft.

Reflection as Foundation

First of all, reflection is necessary. Dinty W. Moore in The Truth of the Matter: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction, points out that while everyone loves a well-told story, “the…reason people care relates to what the writer has made of the experience and how the author’s discovery often rings true for a wide readership.” This reflection can happen before, during, and after the writing of the essay’s initial draft, but it must happen because the writer must be open to new ideas at each level. Otherwise writers may find themselves unwilling to begin because they fear what will come of the writing, stuck partway through because they get mired in the trauma of re-telling their story, or unwilling to revise because they’re still not ready to think about the event at a higher level. I admit this involves mental and emotional issues and maturity as well. As Phillip Lopate notes in the introduction of The Art of the Personal Essay, “It is difficult to write analytically from the middle of confusion, and youth is a confusion in which the self and its desires have not yet sorted themselves out.”

First of all, reflection is necessary. Dinty W. Moore in The Truth of the Matter: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction, points out that while everyone loves a well-told story, “the…reason people care relates to what the writer has made of the experience and how the author’s discovery often rings true for a wide readership.” This reflection can happen before, during, and after the writing of the essay’s initial draft, but it must happen because the writer must be open to new ideas at each level. Otherwise writers may find themselves unwilling to begin because they fear what will come of the writing, stuck partway through because they get mired in the trauma of re-telling their story, or unwilling to revise because they’re still not ready to think about the event at a higher level. I admit this involves mental and emotional issues and maturity as well. As Phillip Lopate notes in the introduction of The Art of the Personal Essay, “It is difficult to write analytically from the middle of confusion, and youth is a confusion in which the self and its desires have not yet sorted themselves out.”

The “how-to” aspect of reflection is difficult because any technique would be contingent on the author’s awareness of the necessity of thinking deeply about the circumstances of her life being examined in the essay, and her willingness to make the conscious decision to do it. These aspects are not always present in a personality. However I would like to venture forward with a few questions a writer may ask if she does want to begin the process of reflection even if she doesn’t know what the answers are or what to make of them. These questions are:

- Why do I want to write about this particular topic/event/circumstance in my life?

- Who was I before this event happened to me?

- Who am I as a result of it? In other words, how do I see the world through the lens of what happened to me?

- How do I feel about the people I’m writing about? Have these feelings changed over time? Have they not? Why?

- What are my physical/emotional reactions around my topic? How fresh is the “wound?”

I would also suggest a writer begin a mental practice of consistently asking these questions during the writing process and whenever a memory or past reference presents itself for consideration. On a positive note, this kind of thinking is open to all, young and old, so younger authors need not despair even if the writing results in musings for which they have no clear answer just yet. The fact that they are questioning and making that apparent may be enough to engage the reader. Many readers appreciate the vulnerability of a writer who is willing to admit she doesn’t know the answers. The fact that she is daring to ask the questions that could reflect the reader’s own silent struggle builds credibility for the writer and will eventually help to create stronger work.

The Four Techniques

This paper will focus on four techniques that can be used by writers who can reflect, have reflected, and want to make their writing connect with as many readers as possible. These craft points can help the writer to open the door for readers, to allow them to more easily share in the emotions, thoughts and events the writer is laying before them.

The first technique involves the use of metaphor. As defined in the Google search dictionary, a metaphor is:

1.) A figure of speech in which a word or phrase is applied to an object or action to which it is not literally applicable.

2.) A thing regarded as representative or symbolic of something else, especially something abstract.

In Elie Wiesel’s memoir of the Holocaust, Night, he tells the horrifying story of his year as a teenager in concentration camps, including Auschwitz and Buchenwald, in which he suffers the deaths of his family members, his friends and, eventually, his own faith. The title Night evokes the metaphor that is the foundation of the whole book. The traumatic material within the covers requires a powerful metaphor. How else can he help the reader grasp the incredible terror and darkness felt by himself and by his people except by connecting it to the darkness we experience regularly and, as children, even fear? It seems every time night falls in the book there is no rest, only fear and concern for what the next day will bring. Night becomes the representation of the darkness cast over Wiesel and his people. He refers to the “nocturnal silence that deprived me for all eternity of the desire to live.” In this section Wiesel combines the metaphor of night with fire to represent the furnaces of the concentration camps:Since in personal essays we deal in the abstract continually, especially when it comes to the writer’s emotions, metaphor becomes essential. Sue William Silverman, in her Vermont College of Fine Arts lecture “Metaphor Boot Camp,” notes the use of metaphor in personal essays allows the writer to make abstract terms or emotions such as the words “love,” “hate,” or “misery,” accessible and tangible for the reader through the use of imagery. This is the answer to the question of how else can the reader relate to a story that only happened to you. It also aids in this question of reflection: “Metaphor helps us to understand what this experience in the past actually meant.”

“No one was praying for the night pass quickly. The stars were but sparks of the immense conflagration that was consuming us. Were this conflagration to be extinguished one day, nothing would be left in the sky but extinct stars and unseeing eyes.”

There is a haunting elegance and beauty in Wiesel’s writing that comes through even in translation. His imagery doesn’t sugarcoat events. If anything it makes them more alive and, though horrifying, accessible. This works because, as Sue Silverman points out in her lecture, “Once you have developed metaphor, you’ve transformed your life into art and all art is universal.”

The second technique involves the direct appeal, in other words, the writer brings the reader directly into the essay with the use of “we” or “society.” The idea is that what the writer is talking about leads us to question or examine the bigger picture and how it affects all of us. The direct appeal assumes a certain kind of reader—a concerned citizen, a reader engaged with the world and who wants to know about actions and their consequences on society at large. It also assumes the writer has set herself up in a certain way: she establishes her authority to validate why she can speak to the bigger picture. Richard Todd would argue this isn’t necessary. “What gives you license to write essays?” he asks in The Art of Nonfiction. “Only the presence of an idea and the ability to make it your own.” But he does acknowledge the importance of training a discerning writer’s eye on the issues of our time and the essay being the right vehicle in which to do so: “An essay both allows and requires you to say something more than you are entitled to say by virtue of your resume alone.”

The second technique involves the direct appeal, in other words, the writer brings the reader directly into the essay with the use of “we” or “society.” The idea is that what the writer is talking about leads us to question or examine the bigger picture and how it affects all of us. The direct appeal assumes a certain kind of reader—a concerned citizen, a reader engaged with the world and who wants to know about actions and their consequences on society at large. It also assumes the writer has set herself up in a certain way: she establishes her authority to validate why she can speak to the bigger picture. Richard Todd would argue this isn’t necessary. “What gives you license to write essays?” he asks in The Art of Nonfiction. “Only the presence of an idea and the ability to make it your own.” But he does acknowledge the importance of training a discerning writer’s eye on the issues of our time and the essay being the right vehicle in which to do so: “An essay both allows and requires you to say something more than you are entitled to say by virtue of your resume alone.”

Eula Biss in her collection of essays, Notes from No Man’s Land, travels back and forth between personal experience and issues such as racism, immigration and education. She lays the foundation of her authority by presenting research she has done. In her essay “Time and Distance Overcome” she connects the innovation of the telephone to another more disturbing American innovation: lynchings. In stating statistics, and quoting newspapers and reports of documented lynchings, Biss creates the framework through which to discuss racism. The facts she presents are aimed to evoke our outrage and disbelief:

“More than two hundred antilynching bills were introduced to the U.S. Congress during the twentieth century, but none were passed. Seven presidents lobbied for antilynching legislation, and the House of Representatives passed three separate measures, each of which was blocked by the Senate.”

This mode of universality is more often used in essays of a journalistic type, but a a personal essay may actually be the better forum. There is less distance between the reader and the concepts discussed because the writer provides the human connection through their personal experiences and observations. The writer can say “I know this is true because it affected my home/my health/my town/my family/my job.” Her observations are not conjecture, but a living example of the concepts she is pondering in the written word. The concepts alone in such essays are big and difficult: racism, immigration, politics, ecology, religion. When the writer offers as a starting point her own experience, it is an easier way for the reader to wade into the waters of discussion. Several times in her book Biss mentions her own reaction to her discoveries—in one instance watching a documentary has her in tears:

“The point at which I began to cry during the documentary about Buxton was the interview with Marjorie Brown, who moved from Buxton to the mostly white town of Cedar Rapids when she was twelve. ‘And then all at once, with no warning, I no longer existed…The shock of my life was to go to Cedar Rapids and find out that I didn’t exist…I had to unlearn that Marjorie was an important part of a community.”

Biss lays the foundation of her argument with such emotion, then walks us backwards to show how she came to this reaction so that we might understand and possibly even feel the same way.

When a writer appeals to the reader to connect to his or her own experience in relation to the author’s, the writer is utilizing the third technique to communicate to a broad audience. The writer can do this by referencing events or actions that most people have experienced such as having children or eating a satisfying meal. Dinty W. Moore writes in The Truth of the Matter, “We all know grief, fear, longing, fairness, and unfairness. We all worry about losing someone dear to us. We crave attention, from everyone, or from certain people. We love our families, yet sometimes those families greatly disappoint us…These basic human worries and emotions will always resonate when brought clearly to life on the page.” In my essay “White Shirts,” I invoke the pain of touching a hot iron: “A burn rises quickly, a living red capsule on the surface of your skin. You think it will never heal because that’s how much it hurts when it happens.” I also conjure the feel of a shirt as it is being ironed: “the shirt large and voluminous in Lena’s small hands, the white cotton hopelessly scorched…” and “Sleeves are tricky because of their roundness. They don’t lie flat well so I will usually iron a sleeve and turn it over to find a funky crease I didn’t mean to create running like a new slash down the arm.” I chose these details because my memories of ironing trigger my senses of touch, sight and smell. This is how I made the words I wrote alive for the reader and myself.

The use of detail with this technique is key. The right details can spark the reader’s memory and cause them to, in the moment, relive their own experience even as they are reading about the author’s. Henry Louis Gates does this successfully in his piece “Sunday,” in which he describes the traditional dinner served weekly in his family home. Dinty Moore points out:

“Much of the intimacy here is in the family secrets Gates chooses to share, and the generous description of the table laden with food: ‘fried chicken, mashed potatoes, baked corn (corn pudding), green beans and potatoes (with lots of onions and bacon drippings and a hunk of ham), gravy, rolls, and a salad of iceberg lettuce, fresh tomatoes (grown in Uncle Jim’s garden), a sliced boiled egg, scallions, and Wishbone’s Italian dressing.’ Instead of a weak line like ‘you can’t imagine how much food there was,’ Gates puts us right at the table.”

I should note this technique is different from the use of metaphor because the detail doesn’t have to represent something else. It can stand on its own representing nothing more than the experience itself—it is the experience that connects the reader. In Night such details are found in the descriptions of thirst and heat as the neighborhood is gathered and made to march without water under the heat of a summer sun: “People must have thought there could be no greater torment in God’s hell than that of being stranded here, on the sidewalk, among the bundles, in the middle of the street under a blazing sun.”

The fourth technique involves the writer hitting upon the right voice in the telling of the story. A reader will react to a writer’s voice with the same discernment anyone would use at a cocktail party—if you don’t like the tone or attitude of the voice talking to you, you’re more likely to move away and speak to someone else. In experiencing a personal essay, a reader will not stay at the “party” if they encounter a voice they feel is arrogant, bossy, pedantic, whiny, annoying or anything else that makes them uncomfortable. The writer’s goal is to establish authority and a likeable voice at the same time. For myself, I deem a voice likeable if it is confident, knowledgeable and, if appropriate, has a good sense of humor. This doesn’t mean the writer has to bend over backwards to make her voice likeable. Some writers do this to the detriment of the work, relying too much on colloquialisms or self-deprecation. Even in the real world, trying to be everyone’s best friend simply doesn’t work and usually results in the person transmitting a bland, false persona. In writing this would translate as beige, uninteresting prose. In developing and considering voice the writer would do well to remember that in doing so, she is also establishing her narrative presence, the person in the room she wants to be. Mimi Schwartz, in her essay, “Memoir? Fiction? Where’s the Line?” says if the writer’s voice is “savvy and appealing enough to make the reader say, ‘Yes, I’ve been there. I know what you mean!—you have something good. But if the voice you adopt annoys, embarrasses or bores because of lack of insight, then beware. The reader will say, ‘So what? I don’t care about you!’ often in anger.”

Having the right voice also gives the writer more leeway in sidestepping the common essay obstacles of egotism and navel-gazing. The nineteenth-century writer Alexander Smith discusses how much can be forgiven a writer if the work is engaging: “The speaking about oneself is not necessarily offensive. A modest, truthful man speaks better about himself than about anything else, and on that subject his speech is likely to be more profitable to his hearers…If he be without taint of boastfulness, of self-sufficiency, of hungry vanity, the world will not press the charge home.”

A writer develops voice through the discerning use of vocabulary, colloquialism, and a general overall sense of camaraderie and shared confidence. When the writer has achieved this, she relates to the reader regardless of age, race, or culture background. James Baldwin, in his reflections on race and his young adult life in Harlem in Notes of a Native Son, develops a voice that is both mature and youthful as he looks back at how certain discoveries and experiences have shaped him and caused him to lose the innocence he once held about his place in society. At his essence, Baldwin’s voice is his connection, authority and narrative rolled into one: I am a human being. And he is most shocked when he finds himself in situations where that simple fact is not acknowledged or respected. “…there must never in one’s own life, accept these injustices as commonplace but must fight them with all one’s strength. This fight begins, however, in the heart and it now had been laid to my charge to keep my own heart free of hatred and despair.”

Such vulnerability and bareness allows the reader to relate to the writer to the point of oneness. “The essayist can also appear as a figure who boasts of little in the way of heightened emotion or peculiarity of feeling,” says Richard Todd in Good Prose. “This sort of writer’s whole claim on the reader is the claim of the norm: I am but a distillation of you.” Indeed, this has been one of the most admired aspects of Baldwin’s book—his ability to reach out beyond his very specific experience to touch, intimately, readers who are nothing like him. In 2012, in an essay published in recognition of the 25th anniversary of Baldwin’s death, the writer Robert Vivian recalls how as a young white man first reading Notes of a Native Son, he felt Baldwin’s voice spoke directly to him:

“…there was something about his voice and how he wrote that felt intimate and familiar and deeply personal, almost as if he were writing in my voice, my skin, my way of looking at the world, which must be why some writing is so capable of addressing the universality of human experience regardless of the very real and limiting facts of people’s lives through the mysterious, sympathetic alchemy of prose that can, in its greatest practitioners, so deeply strum the common chords that make us all one.”

Communicating from No Man’s Land

Eula Biss’s award-winning nonfiction collection, Notes from No Man’s Land: American Essays, is a challenging read because the author takes on some of the most difficult subject matter of our time: race, the loss of self, sociopolitics, immigration and education. But her use of the four techniques described here makes the material easier for the reader to digest. It’s as though Biss is taking readers by the hand and gently leading them on her expedition through No Man’s Land.

The book is organized around Biss’s experiences of different parts of the United States beginning with her time spent in New York, then moving on to California and later the Midwest. It opens with “Time and Distance Overcome,” an essay on racism that sets the tone for the ensuing pieces. It ends with “All Apologies,” a reflection on whether apologies can truly be made and whether real forgiveness is possible when the perpetrators of a wrong are long deceased or apt to commit the wrong again and again.

In her essay “Letter to Mexico” Biss uses the metaphor of the ocean and its tides to communicate the sense of the city of Ensenada being overwhelmed by ever surging numbers of ugly Americans who have, courtesy of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), relieved Mexicans of a good chunk of their wages and manufacturing businesses. The Mexicans are powerless against the influx of Americans just as any person would be powerless against the enormity of the ocean.

“I was confined to the shore there, even when I was not in the tourist district, where the cruise ships unloaded and middle-aged Americans periodically swarmed the bars and souvenir stands then receded like a tide.”

Biss also uses metaphor in her essay “Three Songs of Salvage” to communicate how the ever present rhythm of drums from her childhood when her mother practiced the Yoruba faith still mark time for her today. “I fell asleep to the distant sound of drums, which I was not always entirely sure was the distant sound of drums. Rain, blood in the body, explosions in the quarry, and frogs are all drums…I know now that I left home and I left the drums but I didn’t leave home and I didn’t leave the drums. Sewer plates, jackhammers, subway trains, cars on the bridge, and basketballs are all drums.”

Biss frequently uses the direct appeal in “Is This Kansas” to challenge the reader to question how we view the behavior of college students and the connection of that thinking to what our society looks like. There is a chiding nature to her comments as she presents her observations. The reader might feel she’s being called out by Biss because the reader may very well have one of views the writer highlights. If the reader does have such a view then a crack has been opened and Biss has the opportunity to make the reader see things in a different light.

“I would often wonder, during my time in that town, why, of all the subcultures in the United States that are feared and hated, of all the subcultures that are singled out as morally reprehensible or un-American or criminal, student culture is so pardoned. Illinois home owners propose ordinances against shared housing among immigrants, while their sons are at college sharing one-bedroom apartments with five other boys. Courts send black teenagers to jail for possession of marijuana, while white college kids are sentenced with community service for driving while intoxicated, a considerably more deadly offense. And Evangelicals editorialize about the sexual abominations of consenting adults, while very little is said about the plague of date rapes in college towns.”

In using details to connect the reader to their own experiences, Biss helps the reader experience with new eyes a place such as New York City that the reader may only know through movies or television show myths. She appeals to their sense of loneliness, alienation, and even fear because that was so much her own experience of the city. Biss anchors all of this with details that engage the reader’s senses.

“I could see barges silhouetted against the hazy pink horizon at dusk. I tried to walk down to the water and promptly dead-ended at a huge, windowless building labeled Terminal Warehouse.”

“The station at Coney Island was half-charred form a fire decades ago and packed with giant inflatable pink seals for sale…Caramel apples were seventy-five cents and the din of the fair games was intolerable. One freak-show announcer screamed, ‘If you love your family, you will take them to see the two-headed baby!’ It was gross and crazy and base…The beach was packed with naked flesh and smelled like beer and mango. And the Wonder Wheel inspired real wonder as I rose up over Brooklyn in a swinging metal cage.”

The voice Biss develops in her book has an intriguing mix of vulnerability and authority. From a writer’s standpoint such a voice puts you exactly where you want to be with the reader: the vulnerability helps to establish trust and rapport; the authority seals your credibility. The reader will listen to what you have to say. We feel for Biss in her youthful questioning of her guilt, her feelings about her race, her fear. But she is fearless when it comes to delving into research to support her marked disturbance and indignation over attitudes, traditions and social norms. In “Land Mines” she discusses the failures of the education system, first establishing herself as a participant in that system, and then examining policies she has directly read or experienced. Her indignation sometimes seems close to bubbling over when she describes the University of Iowa’s considerations for how to make their school more diverse in ways that do not consider the well-being for their diverse students.

“One didn’t need to spend very long at that institution before realizing that the interests of everyone else—the funders, the administrators, the professors, the graduate students—came before the interests of the undergraduate students. And as in any feudal system, the people on whom the entire system depended were robbed, as completely as possible, of their power.”

Her essay “No Man’s Land” has a voice presenting Biss’s views with wide-eyed clarity. She puts herself, as well as society, under the microscope as she compares her experiences in the slowly gentrifying Chicago neighborhood of Rogers Park with the observations of Laura Ingalls Wilder of how the white man usurped the lands of the native Americans. Biss establishes her voice with direct rhetoric, using her research and her strong point of view to ground her statements about “pioneering” in America and what that really means—in one example it means unjustified fears:

“This is our inheritance, for those of us who imagine ourselves pioneers. We don’t seem to have retained the frugality of the original pioneers, or their resourcefulness, but we have inherited a ring of wolves around a door covered only by a quilt. And we have inherited padlocks on our pantries. That we carry with us a residue of the pioneer experience is my best explanation for the fact that my white neighbors seem to feel besieged in this neighborhood. Because that feeling cannot be explained by anything else that I know to be true about our lives here.”

Biss’s voice also makes it easier for readers who may be longtime fans of Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books to look at the series in a different way. If Biss had been too harsh the reader could have been led to misinterpret the essay as a criticism of the books. Instead Biss shows respect for the author and, in turn, her own readers as she follows through with her observations.

Mining the Night

As mentioned earlier, Elie Wiesel in his memoir Night uses the night as a long-form metaphor to invoke the darkness and horror of his experience as a teenager in the concentration camps of Auschwitz and Buchenwald during the Holocaust. But he also uses other metaphors and the rhetorical techniques discussed here to draw as many people as possible into the intimate nature of his pain and despair.

The book opens in 1941 with Wiesel as an eager 13-year-old student of the Talmud. When the “foreign Jews” including his own Kabbalah teacher, Moishe the Beadle, are removed from their town of Sighet, Transylvania, few members of Wiesel’s community read the action as the precursor of the horrors to come, even after Moishe escapes and returns with his eyewitness account of the killings of the deported Jews. Wiesel details the downward spiral of his people’s condition and their continued hope that things will get better until, sealed in rail cars, they can no longer ascribe to the delusion.

The powerful emotions related in Night require metaphor to help the reader access the book’s hard moments of despair and desolation. “Not far from us, prisoners were at work,” he writes, “Some were digging holes, others were carrying sand. None as much as glanced at us. We were withered trees in the heart of the desert.” Pain on such a scale can only be abstract to the outside observer. But metaphor, as noted from Sue Silverman’s lecture, allows Wiesel, in beautiful language, to turn his experience, though terrible, into art that the reader can take in and be in.

Wiesel uses the direct appeal technique in a different way. Instead of speaking directly to or challenging his readers, he is making the appeal by telling his story. It is an implied appeal: Wiesel is telling his story so he can bear witness to these atrocities to the world. In turn the readers learn from his testimony and the appeal is that we don’t allow such atrocities to happen again. He says this directly in the book’s introduction. It is the whole reason for the book’s existence and the reason Wiesel does his best to help the reader look, not look away.

“For the survivor who chooses to testify, it is clear: his duty is to bear witness for the dead and for the living. He has no right to deprive future generations of a past that belongs to our collective memory.”

There’s also, I believe, an appeal present in the undercurrent when Wiesel and the people around him more than once wonder at how and why the rest of the world didn’t know the extermination of the Jewish people was in progress. And if they did know, why wasn’t anyone saying or doing something about it? “How was it possible that men, women, and children were being burned and that the world kept silent? No. All this could not be real.” This, to me, feels like Wiesel’s call to all readers to be awake to the occurrences of the world, no matter what country.

In terms of details, Wiesel frequently activates the reader’s senses through his descriptions of pain, heat, cold, smells, colors, and more. In early parts of the book, his descriptions of spring recall the normal aspects of the season: brilliant skies, beautiful blossoms, delicate smells and bright green grass. This is the part the reader can relate to. Then he overlays the fear of the Germans and the transfer into the ghettos. He also uses the details of home, the trappings of home, to communicate to the reader what is being left behind. When he and his family enter the home of family members who have been transported away, they find “the chaos was even greater here than in the large ghetto. Its inhabitants evidently had been caught by surprise…On the table, a half-finished bowl of soup. A platter of dough waiting to be baked. Everywhere on the floor there were books. Had my uncle meant to take them along?”

When describing the camp’s horrors Wiesel’s descriptions become more physical:

“We whispered. Perhaps because of the thick smoke that poisoned the air and stung the throat.”

“An SS officer had come in and, with him, the smell of the Angel of Death. We stared at his fleshy lips.”

“ ‘It doesn’t hurt.’ His cheek still bore the red mark of the hand.”

The voice Wiesel uses often sounds like that of a witness giving testimony, which is exactly what he is doing. In fact, one reviewer refers to the book not as a memoir or essay, but as a “human document.” But Wiesel also has a poetic rhythm in much of the work that mesmerizes the reader with the beautiful depth of his dark musings. There is a natural vulnerability that comes through because of the youth of Wiesel’s narrative character during the events. He is at once sympathetic and authoritative with being strident, accusatory or vengeful. This makes Wiesel all the more believable, because he has created a voice that doesn’t seem prone to exaggeration or puffed up with hyperbole. Even when an observation could seem outsized, the words are presented with such gentle calmness that the reader can’t help but take them seriously. This happens, for example, when he conjures the image of he and his campmates as lost souls condemned to a kind of purgatory from which they can never escape.

“In one terrifying moment of lucidity, I thought of us as damned souls wandering through the void, souls condemned to wander through space until the end of time, seeking redemption, seeking oblivion, without any hope of finding either.”

At times Wiesel’s rhetoric is straightforward such as in instances when he uses repetition to evoke emotion. The repetition of the word “never” in the following passage, for example, has the heaviness of a hammer driving home the losses Wiesel knows he must live with for the rest of his life.

“Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, that turned my life into one long night seven times sealed.

Never shall I forget that smoke.

Never shall I forget the small faces of the children whose bodies I saw transformed into smoke under a silent sky.

Never shall I forget those flames that consumed my faith forever.

Never shall I forget the nocturnal silence that deprived me for all eternity of the desire to live.

Never shall I forget those moments that murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to ashes.

Never shall I forget those things, even were I condemned to live as long as God Himself.

Never.”

The Voice of Inclusion

James Baldwin’s 1955 essay collection Notes of a Native Son is described on the cover of the 1979 paperback edition as “the moving chronicle of Baldwin’s search for identity as a writer, as an American, and as a Negro.” At the time of its writing, a time in America where segregated bathrooms, restaurants, hotels and transportation still existed, such subject matter could easily be considered singularly personal and exclusive. However, Baldwin’s work succeeded in accessing an audience so broad that the work is still considered relevant both to society as a whole and to each individual reader who experiences it.

The first part of the book features Baldwin’s unflinching assessment of creative works including the abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the film Carmen Jones, and Richard Wright’s novel Native Son, and his examination of what they have to tell us about current views on the mythical perceptions of Negros especially concerning issues of skin tone, sexuality, and cleanliness. Baldwin then moves into personal reflection regarding his life in Harlem, memories of his father, and his frustration with the realization that racism will affect him regardless of how clean, educated or well spoken he is. These reflections go deeper as Baldwin’s insecurities are laid bare in Paris where he is arrested for a menial crime and incarcerated in a system that cares little for his rights or personal comfort.

Baldwin uses his most powerful metaphor in the opening paragraphs of the book’s title essay. He describes the race riots in Harlem that took place after his father’s funeral and the smashed glass in the streets become, for Baldwin, a representation of the apocalypse—a destruction of a world he has known and a harbinger of the unknown world he is entering.

“A few hours after my father’s funeral, while he lay in state in the undertaker’s chapel, a race riot broke out in Harlem. On the morning of the 3rd of August, we drove my father to the graveyard through a wilderness of smashed plate glass…And it seemed to me, too, that the violence which rose all about us as my father left the world had been devised as a corrective for the pride of his eldest son. I had declined to believe in that apocalypse which had been central to my father’s vision; very well, life seemed to be saying, here is something that will certainly pass for an apocalypse until the real thing comes along.”

At the end of the section, this metaphor returns when Baldwin hurls a water glass at a restaurant waitress who refuses to serve him. The glass hits a mirror behind the bar and shatters. This gives rise to another metaphor, this time evoking the cycle of freezing and thawing, and how in this moment, Baldwin “thaws” and is freed from a frozen state of anger and boldness which then moves him to a state of fear.

“She ducked and it missed her and shattered against the mirror behind the bar. And, with that sound, my frozen blood abruptly thawed, I returned from wherever I had been, I saw, for the first time, the restaurant, the people with their mouths, open, already, as it seemed to me, rising as one man, and I realized what I had done, and where I was, and I was frightened.”

Baldwin does not make direct appeals so much as direct observations of America as a whole or large, significant groups within it such as the “Progressive Party” or the “optimistic American liberal.” These observations challenge the status quo, with Baldwin unafraid of declaring when he feels a situation is unacceptable. At the time of his writing this fearless tone would have made Baldwin’s readers uncomfortable about their own commitment. They also might feel concern over the risk of a Black writer speaking so plainly when he could still suffer the consequences of his words.

“Finally, we are confronted with the psychology and tradition of the country; if the Negro voter is so easily bought and sold, it is because it has been treated with so little respect; since no Negro dares seriously assume that any politician is concerned with the fate of Negroes, or would do much about it if he had the power, the vote must be bartered for what it will get…The American commonwealth chooses to overlook what Negroes are never able to forget: they are not really considered a part of it.”

In his essay “Equal in Paris” Baldwin uses detail to convey the fear and alienation of his days-long incarceration in a French prison. It’s interesting how a few of these details are not all that different from the ones Wiesel chose to describe the cells at the concentration camps. Baldwin allows the cold, the hole that served as a common toilet, the narrow cubicles, and the very fact that he begins to cry, to communicate to the reader the dire nature of his situation and his emotional condition. At one point, during his transport to another facility, “I remember there was a small vent just above my head which let in a little light. The door of my cubicle was locked from the outside. I had no idea where this wagon was taking me and, as it began to move, I began to cry. I suppose I cried all the way to prison…”

As mentioned earlier, Baldwin’s voice has served to connect to readers who find his voice so familiar that they identify with him, even across the wide canyon of time. It’s interesting that readers react to him this way because I didn’t find the voice particularly friendly or appealing. Baldwin has a formality about his phrasing and choice of words that, to me, make me feel he wasn’t an easy person to get to know in real life.

“But it is part of the business of the writer—as I see it—to examine attitudes, to go beneath the surface, to tap the source.”

Perhaps he felt this formality was necessary for the time and his subject matter. I can respect this choice. He was, after all, still a young man when Notes of a Native Son was published. He wanted to write about his thoughts on serious matters and in order to be taken seriously he had to establish his sound of gravitas. This is his business as a writer. However, I believe he also understood the importance of letting the reader know he is a real person and he does that effectively as well. In his “Autobiographical Notes” at the beginning of the book there is some hint of warmth as Baldwin notes how he loves to laugh and talks about his commitment to his writing.

“…I love to eat and drink—it’s my melancholy conviction that I’ve scarcely ever had enough to eat…and I love to argue with people who do not disagree with me too profoundly, and I do love to laugh. I do not like bohemia, or bohemians, I do not like people whose principal aim is pleasure, and I do not like people who are earnest about anything…I consider I have many responsibilities, but none greater than this: to last, as Hemingway says, and get my work done.

I want to be an honest man and a good writer.”

Maybe that’s the Baldwin readers connected with first, and that is the voice they carried with them as they read the ensuing essays. He has introduced himself as a respectably amiable person. There’s no reason for the reader not to want to accompany Baldwin on his musings.

Conclusion

Though the focus of this exploration has been how to reach the broadest possible audience, I believe every piece of writing, at its heart, is an author’s attempt at conversation with just one reader. In many cases the writer knows at the outset the communication will be a difficult one, akin to two people speaking different languages. The writer, in order for her endeavor (which is to tell a story or relate an experience) to be successful, must try as many ways as possible to bridge the gap of understanding. If she can manage to do that, the happy result may be a bridge that more than one reader can utilize. In fact it can be used again and again, with readers crossing from all angles. In this way the writer achieves the broader audience.

The techniques described here can hopefully be the building materials a writer uses to build this bridge, keeping in mind that even the use of just one can bring a reader closer to relating to the writing than if she attempted none of them.

—Sophfronia Scott

————————-

Works Cited

Baldwin, James. Notes of a Native Son. Toronto [u.a.]: Bantam, 1979. Print.

Biss, Eula. Notes from No Man’s Land: American Essays. Saint Paul, MN: Graywolf, 2009. Print.

Glover, Douglas “How to Write a Short Story: Notes on Structure and an Exercise.” Attack of the Copula Spiders: And Other Essays on Writing. Emeryville, Ont.: Biblioasis, 2012. 23-42. Print.

Kidder, Tracy, and Richard Todd. Good Prose: The Art of Nonfiction. New York: Random House, 2013. Print.

Lopate, Phillip. “Introduction.” Introduction. The Art of the Personal Essay: An Anthology from the Classical Era to the Present. New York: Anchor, 1994. Xxiii-Liv. Print.

Moore, Dinty W. The Truth of the Matter: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction. New York: Pearson/Longman, 2007. Print.

Scott, Sophfronia. “White Shirts: Essay — Sophfronia Scott.” Numero Cinq. N.p., Sept. 2012. Web. 03 Apr. 2013.

Scott, Sophfronia. “Writing Your Heart Open.” Hunger Mountain: The VCFA Journal of the Arts. Hunger Mountain, 20 Sept. 2012. Web. 21 Apr. 2013.

Vivian, Robert. “Baldwin in Omaha.” Hunger Mountain: The VCFA Journal of the Arts. Hunger Mountain, 6 Dec. 2012. Web. 03 Apr. 2013.

Wiesel, Elie. Night. New York: Hill and Wang, 2006. Print.

William Silverman, Sue. “Metaphor Boot Camp.” Vermont College of Fine Arts, MFA in Writing Residency. College Hall Chapel, Montpelier, VT. 4 Jan. 2013. Lecture.

End Notes

INTRODUCTION

Glover, Douglas H. “How to Write a Short Story: Notes on Structure and an Exercise.” Attack of the Copula Spiders: And Other Essays on Writing. Emeryville, Ont.: Biblioasis, 2012. 23-42. Print

Kidder, Tracy, and Richard Todd. Good Prose: The Art of Nonfiction. New York: Random House, 2013. Print.

Lopate, Phillip. “Introduction.” Introduction. The Art of the Personal Essay: An Anthology from the Classical Era to the Present. New York: Anchor, 1994. Xxiii-Liv. Print.

Moore, Dinty W. The Truth of the Matter: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction. New York: Pearson/Longman, 2007. Print.

Scott, Sophfronia. “White Shirts: Essay — Sophfronia Scott.” Numero Cinq. N.p., Sept. 2012. Web. 03 Apr. 2013.

Scott, Sophfronia. “Writing Your Heart Open.” Hunger Mountain: The VCFA Journal of the Arts. Hunger Mountain, 20 Sept. 2012. Web. 21 Apr. 2013.

THE FOUR TECHNIQUES

Gates, Henry Louis. “Sunday.” As published in The Truth of the Matter: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction. New York: Pearson/Longman, 2007. Print.

Moore, Dinty W. The Truth of the Matter: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction. New York: Pearson/Longman, 2007. Print.

Lopate, Phillip. “Introduction.” Introduction. The Art of the Personal Essay: An Anthology from the Classical Era to the Present. New York: Anchor, 1994. Xxiii-Liv. Print.

Schwartz, Mimi. “Memoir? Fiction? Where’s the Line?” As published in The Truth of the Matter: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction. New York: Pearson/Longman, 2007. Print.

Vivian, Robert. “Baldwin in Omaha.” Hunger Mountain: The VCFA Journal of the Arts. Hunger Mountain, 6 Dec. 2012. Web. 03 Apr. 2013.

——————————

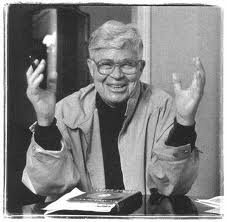

Sophfronia Scott recently completed her second novel, Lady of the Lavender Mist, and has essays in two new Chicken Soup for the Soul books: Inspiration for Writers (May 2013) and Reader’s Choice 20th Anniversary Edition (June 2013). She published her first novel, All I Need To Get By, with St. Martin’s Press in 2004. Her work has appeared in Time, People, More, NewYorkTimes.com, Sleet Magazine, Gently Read Literature, The Mid-American Review, The Newtowner, and O, The Oprah Magazine. Sophfronia is currently a masters candidate in fiction and creative nonfiction at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her short story, “Murder Will Not Be Tolerated,” will be in the Fall 2013 issue of The Saranac Review. She blogs at www.Sophfronia.com.