The come-and-go as you please nature of the text, which allows for any entry point, equalizes the information. There is a sense that it’s all happening at once, and that knowing when Levé hears the English word “god” he thinks of the French word for dildo (godemiché) is as important as his druthers to “paint chewing gum up close than Versailles from far away.” — Jason DeYoung

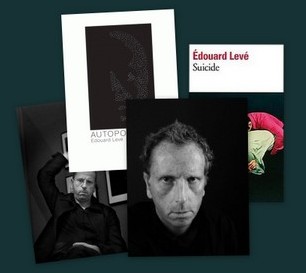

Autoportrait

Edouard Levé

Translated by Lorin Stein

Dalkey Archive, 2012

117 pages, $12.95

Edouard Levé took his own life ten days after delivering his final novel Suicide to his publisher. Assembled pointillisticly, Suicide is without much narrative, but Levé holds your attention through insights regarding the act of suicide and his patient rendering of a man who takes his own life at the beginning of the book. There is a lot of guesswork on the part of the author in Suicide, but Levé manages to give a poignant depiction of this young man, his personality, eccentricities, and motivations. Autoportrait and Suicide resemble each other in style, except the former is about Levé himself, and Autoportrait is without the latter’s lucidity, which is in keeping with Levé’s philosophy, as he writes: “Only the living seem incoherent. Death closes the series of events that constitutes their lives. So we resign ourselves to finding a meaning for them.” When it was written, Autoportrait was about a living person.

Before Suicide, Levé was better known as a conceptual photographer than a writer. His photographs were often composed scenes that were not as transparent as their titles would suggest, as in his collection Pornography in which models, fully clothed, contort into sexual positions, or his collection Rugby, a series of photographs of men in business attire playing the titular sport. In both, the photos represent an action but are not the real thing. As Jan Steyn points out in the Afterward to Suicide: “We cannot see such images and naively believe in the objective realism to which photography all too easily lays claim: we no longer take such photos to show the truth.”

Levé background also includes a degree from the ESSEC, a prestigious Parisian business school, and for several years he painted before giving it up during a trip to India. His writing owes a self-acknowledged debt George Perec, a founding member of the Oulipo, short for Ouvroir de littérature potentielle—”workshop of potential literature”—and Levé authored two other books: Oeuvres (2002), an imaginary list of more than 500 books by the author, and Journal (2004), a collection of faux journalism.

As a book, Autoportrait is a radical act of communication, eschewing the complexity of organized thought for the chaos of raw fact. Written exclusively in declarative sentences, Autoportrait gives an unflinching self-portrait of its author. In one unadorned assertion after another, Levé creates something personal and individualistic that hints at the multitudes within, while abstaining from narrative (and its attendant techniques): “On the train, facing backward, I don’t see things coming, only going. I am not saving for my retirement. I consider the best part of the sock to be the hole.” Levé own description of “picking marbles out of a bag” aptly describes the apparent order of sentences as they appear over the 117-page, single-paragraph Autoportrait.

If on first encounter Autoportrait seems to be about self-knowledge, it’s not an Apollonian know yourself, find strength within type, but a ridged self-unpacking, brusque and inexplicable. Page-after-page Levé makes stochastic announcement regarding his life—we find out that he is “happy to be happy,” he likes John Coltrane, and could never “conceive of being altruistic.” Yet, as readers, we are left wondering if these facts get close to self-knowledge, or a complete self-knowledge. There is no reading into these facts by the author, interpretation being something that bubbles up from the bowels of opinion, which can be rendered untrue. Though precisely written and hewed rigorously to its form, in the end Levé is still oblique, only a phantom of a person has emerged. Levé knows it; he knows his project is a failure of completeness, and throughout the book he drops hints:

“Everything I write is true, but so what?”

“I write fragments.”

“I know how much I’m seen, but not how much I’m understood.”

“Often I think I know nothing about myself.”

“To describe my life precisely would take longer than to live it.”

Not that he trusts writing anyway: “When I read the descriptions in a guidebook, I compare them to the reality, I’m often disappointed since they are fulsome, otherwise they wouldn’t be there.”

So if the author thinks writing is flawed, why read the book? One reason is for the interests in the formal experiment of its style. Levé has dropped the illusion of narrative to write a frenzy of sentences utterly transparent, crystal-rim-tap clear, yet sentences that do not seem to add up to anything other than lists—likes, dislikes, experiences, wishes, complaints, thoughts, et cetera. A type of graffiti: I am here, such-and-such date, expletive! Existence proven. But without the typical author manipulation afoot, the experience of reading Autoportrait is profound, the way gazing upon a sobbing nude man walking into church during Sunday service might be profound. Asking what does it mean cannot be helped. And the lack of connecting tissues creates its own tension—each sentences something wholly new. What bit of sexual exploit will he confess next, what tidbits of triviality will he express, who else bores him, what other banality will he mention—“My fingernails grow for no reason.” Yes, a genial, yet mordant, whimsy lurks in these sentences.

By taking the book’s title and Levé’s photography into consideration, there is another way to read this book. The come-and-go as you please nature of the text, which allows for any entry point, equalizes the information. There is a sense that it’s all happening at once, and that knowing when Levé hears the English word “god” he thinks of the French word for dildo (godemiché) is as important as his druthers to “paint chewing gum up close than Versailles from far away.” Reading it this way makes me wonder if his intention wasn’t a book that gave a complete picture—how could it really?—but that each sentence be a portrait unto itself, as a camera on “auto” would rapidly shoot pictures. Each sentence a glimpse of a Levé in fixed space and time, a portrait album in sentence form. Thus the visual appearance of a single paragraph book acts as a kind of compression device to create intriguing relationships. But the relationships are so many or so diffuse that Autoportrait becomes a book without a single solution, and in some ways there’s something to relish in its resistance to interpretation, a kind of aesthetic of incomprehensibly in which Levé escapes a tyranny of meaning or acknowledges the absences thereof. As in his photography, these sentences represent their author, but are not the real thing.

As Levé dabs off facts we see there are common ruminations and patterns, however, to his life that revel depth and elicit emotion. And as a wandering mind often does, the book at times comes together for what could be perceived as sustained thought, as in this passage about Levé’s brother:

My brother had two childhood friends, they were all about five year old, and he met them again when he was forty-five in Nice, where all three of them now live. I have no friends from my childhood. When I was a child, then a teenager, I had one best friend for two or three years, then another, and so on, I never kept a best friend more than four years, I was almost twenty before I had the friends who lasted longer, and almost thirty before I met the friends I have now. I have been more faithful in friendship than in love, which isn’t to say that I cheated on the women I was with, but that my relations with them lasted a shorter time than relations with my friends. In every friend I am looking for a brother. I have not found a friend in my brother, but I have not, alas, made the effort to look. My brother was too old for us to be friends. My brother and I are like night and day, and I may be the night. I have often thought that education had little influence over individuals, since my brother and I had the same education and have pursued divergent paths. I like my brother, this is probably reciprocal, I write “probably” because of my brother we have never discussed it. It moves me to see photos of my brother when he was little, I see that we have the same complexion, the same eyes, the same hair, but I know these similar envelopes contain minds that have never come into contact. At night it reassures me to hear a few quiet footfalls on the floor of the apartment above.

This is perhaps my favorite part of the book, since in his comparison with his brother, we glimpse a Levé that isn’t somehow held fast in cool prose, we get something like emotion when he writes, “in every friend I am looking for a brother,” with a second meaning of brother emerging. Levé expresses a desire for reconnection and wholeness. He is “moved” to see pictures of his brother. He wants this relationship. And, for me, that final sentence is the kicker. Though it could be seen as a return to the normal course of the book—one unconnected sentence after another—there’s something haunting there with the footfall, the acknowledge, “reassuring” presence of the another. It heightens the pathos felt in his desire for finding the “aleph of the other” (Suicide). Yet Levé will not let his desire for oneness overpower his art. Autoportrait is fragmentary after all. It’s not a machine for producing a so-called reality. Wholeness, at this point, would be fantasy, and the very next sentence after this passages reads: “I do not eat candy, it makes me sick.”

Dodie Bellamy writes in her Barf Manifesto: “Sophistication is conformist, deadening. Let’s get rid of it.” And that’s what Levé has done here, and that’s what makes Autoportrait extraordinary. Levé has opened himself up to kind of psychological vivisection to show us the mess of his living innards. Yes, some of Levé is exotic—he is an individual after all—but there’s plenty of loneliness and small-heartedness, biases and loves to commiserate with, too. Reading Autoportrait with the same criteria as reading a standard novel built out of plot, character, and setting won’t do. It has to be approached as innovative art: its subject is one person and its form is just as unique.

— Jason DeYoung

————————————–

Jason DeYoung, a regular contributor to these pages, lives in Atlanta, Georgia. His work has recently appeared in Corium, The Los Angeles Review, The Fiddleback, New Orleans Review, and Numéro Cinq.