This photo was taken in the 1980s with my grandmother and her grandchildren. I’m the tallest one. —BK

This photo was taken in the 1980s with my grandmother and her grandchildren. I’m the tallest one. —BK

Bunkong Tuon’s grandmother carried him out of Cambodia on jungle trails on her back. In California, he was a lost kid, a dropout working in a donut shop, too bereft to find a footing in the West. One day he pulled a book off a library shelf and it changed him. The book and the author became this fatherless exiled orphan’s new father. You can read about this in his wonderful essay “On Fathers, Losses, and Other Influences,” published on NC in February.

This time we have a handful of BK’s poems about his grandmother. They will break your heart.

They will break your heart, not through design but because BK knows how to pare his poems down to their emotional core; he knows how to get out of his own way. Like his poetic father, Charles Bukowski, he is a master of sentiment without being sentimental. BK writes: “My tongue has been cut / to fit the meter of another world,” which is a nod to his refugee roots, his loss of his native Khmer language. But here it is almost a conceit, for his heart speaks English all the same, and his poems are a remarkable testament to the power of one woman’s love and determination and the author’s own redeeming spirit.

All my life I told myself I never knew

suffering under the regime, only love.

This is still true.

dg

—

My collection of poems, Under the Tamarind Tree, is a story of leaving Cambodia, living in refugee camps, and growing up in the United States, exploring both the history and culture of Cambodia and the early experience of a refugee in America. I write about Cambodia’s rice paddies, water buffaloes, early memories of my mother and father, life in the refugee camp on Thailand-Cambodia border; I also write about growing up as a refugee in Revere and Malden, MA, in the early 80s, collecting bottles and cans, getting into fights after school, feeling culturally alienated, discovering the work of Charles Bukowski in a Long Beach public library, teaching at a small liberal arts college in the East Coast; in short, the emergence of a hyphenated Khmer-American identity.

—BK

§

Dead Tongue

We are each other’s

springboard to another world.

I search for mother in you,

and you see your daughter in me.

I never knew how to thank you.

The words don’t sound right.

My tongue has been cut

to fit the meter of another world.

The words bounce off walls,

deflated, a dead poem.

Gruel

We were talking about survival

when my uncle told me this.

“When you were young,

we had nothing to eat.

Your grandmother saved for you

the thickest part of her rice gruel.

Tasting that cloudy mixture

of salt, water, and grain, you cried out,

‘This is better than beef curry.’”

All my life I told myself I never knew

suffering under the regime, only love.

This is still true.

Calling Home

My cousin left me this message:

“Grandmother fell in the bathroom

and hit her head against the sink.

There’s a small gash over her right eye.”

I call home, and my uncle answers.

“No need to worry. You can’t talk to her.

She’s sleeping now. How’s work?

When will you be up for that review?”

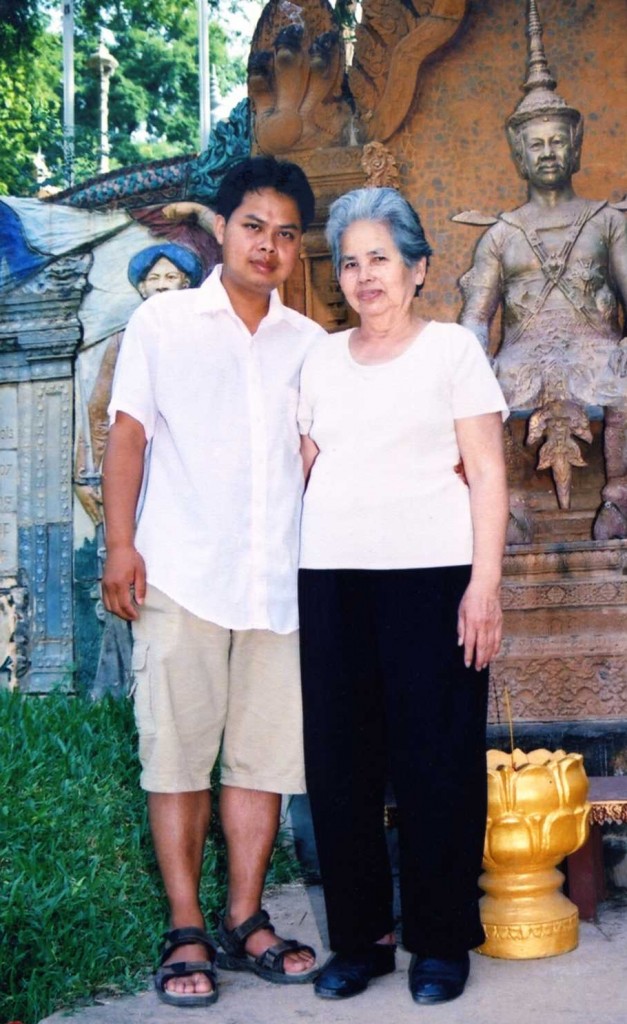

This picture (of grandmother and me) was taken in 2004 at Wat Phnom, in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

This picture (of grandmother and me) was taken in 2004 at Wat Phnom, in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Breakfast with Grandmother

Her maroon beanie, a Christmas gift

from one of her grandchildren,

rests snugly on her shaved head,

a stained bib around her neck.

The pills, crushed in a spoon,

sprinkle the murky gruel.

The water must be heated

to the right temperature, somewhere

between hot and not warm enough.

She cries each time one of us leaves

and is surprised when we return.

I sit at the table trying

not to stare at the cut near her temple,

watching her eat her breakfast,

to let her know that I am here

for her

when suddenly she screams in pain.

Afterward, she sobs quietly,

starring into the gruel

of Jasmine rice, chicken broth,

and now, tear and mucus.

Dining in Chinatown

My twenty-eight year-old cousin says,

before putting a piece of sesame beef into his mouth,

“She can’t be lonely. She has everyone by her side,

her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.”

He pours chili oil over black and pepper squid,

and continues, “Whatever she needs, we get for her.

Food, medicine. She has Elder Uncle who sleeps

in her room to make sure all her needs are met.

Unlike some of her friends whose children

are all over the States, she’s lucky to have us around.”

I watch, fascinated by his ability to take in all that food.

Maybe he’s making up for all that lost time

in the refugee camp. “And that damaged nerve of hers,

her pain stops whenever you’re around. It’s psychosomatic,

or something like that. I don’t know. You’re the Ph.D.”

Exile

On the couch she watches

her great-grandchildren chase

each other down the hallway.

Commanded by the eldest,

they are Power Rangers battling

some evil robot.

A smile flickers.

Memory lit, before it disappears

into darkness again.

Early October, My Cousin’s Four-Year-Old Daughter’s Birthday

Our house booms with noise—four generations under one roof. My grandmother, uncles and aunts, me and my cousins, and their children. Grilled chicken, steak, fried rice; hot dogs, hamburgers, potato salad. Soda pop and beer. The kids are chasing each other in the hallway that connects the living room to the kitchen. I sit with the adults around the dining room table. Grandmother is having her lunch of finely crushed rice powdered with her daily medicine.

—She’s fine. The doctor says she needs to exercise.

—I try to get her to move around. She walks a couple times between here and the living room, then sits on the couch, and seconds later, she’ll be snoring.

—She sleeps too much during the day. At night, she keeps all of us up with her night talks, about her husband, her young brother, our missing brother, and your mother.

—I get goose bumps sometimes, listening to her talk like that.

—Doesn’t she want to go to the temple anymore? She has friends there and the monks really like her. Didn’t they come to bless her in August?

—Her friends are old, too. Grandma Jeat passed away last month from cancer. She was sixty three. Grandma is eighty-four.

—She needs to get out of the house and be with people her own age. I see her sitting by herself in the living room watching the kids run amok and yelling at them to speak Khmer.

—She’s out of breath just walking from here to the bathroom. Besides, it’s getting cold outside. She can’t handle the weather that well now.

—When is her next doctor’s visit? I’d like to go with you, Uncle.

Staring at each of our faces,

Grandmother speaks in clear, measured Khmer:

“Why is everyone speaking English?

You think I don’t know that you’re talking about me?

‘Doctor.’ ‘Hospital.’ ‘Yiey Jeat.’

I’m no dummy. ”

.

A Lesson

I tell myself.

There must be a lesson

in old age.

As the body withers,

truth appears.

It’s wishful thinking,

but it’s good

to think of hope

and renewal

in something beyond

our control.

But, seriously,

how long can we

ask this

of our elders?

How long can we

ask this

of ourselves?

Thanksgiving Farewell

Grandma is holding my wife’s hand:

Take care of each other.

He doesn’t have any parents.

I’ve taken care of him

since his mother passed

away under Pol Pot.

Grandma sobs and turns to me:

Tell her. Speak for me.

She places my hand on top of my wife’s:

You. He. Take care.

Seeing our stunned faces, she repeats.

You. He. Take care. OK?

I give her a hug and say in Khmer:

There’s no need to cry, Lok-Yiey.

We’ll be back around Christmas.

Breathing In

Waiting for the broth to boil,

so that I can drop in the noodles

That Grandma used to make,

I imagine that phone call

from home,

The kind you see in the movies,

where a couple is awakened,

Two in the morning,

fumbling in a darkness

That will never leave.

I breathe in

to become part of you.

—Bunkong Tuon

———————-

Bunkong Tuon teaches in the English Department at Union College, in Schenectady, NY. He completed a book of poems, “Under the Tamarind Tree.” These Grandmother poems are from this collection. Inspired by the reception of his essay “On Fathers, Losses, and other Influences,” he is currently working on a book of essays on family, memory, and home.