Meditative and passionate, Shadow Play works its way toward an approximate answer to the question it opens with, a quotation from Roland Barthes: “How does a love end? —Then it does end?”

—Jason DeYoung

Shadow Play

Jody Bolz

Turning Point Books, 2014

$16.20, 77 pages

ISBN: 978-1625490575

.

T

o imagine talking to a former lover about shared history is ordinary, but in Jody Bolz’s new book, Shadow Play, she takes this common lover’s discourse a step further when her narrator conjures the voice of her ex-husband to the page to recount the exhilaration and eventual dissolution of their all-too-young marriage. In this examination of estrangement, through the scrim of memory in lyric and fragmented narrative, its characters perform a complex and, at times, spectral dance, rich in emotional immediacy.

A novella in verse, the first poem in Shadow Play gives the impression that what is to come will be a standard book of poems. Brightly drawn, untitled, it’s a story of a train trip through Asia, where the narrator and her husband “slept in a knot” for “two hundred miles.” In these sensuous and vivid lines, their love and marriage is secure, a “common life, flown / above another Asian city.” Yet happiness is short-lived, and the second poem drops us from this nimbus of young love as the narrator lays bare her intentions, which portend more vexing complexities:

I’m shaping a mosaic

out of broken bits…

not exactly a gift.

Not exact—

Reflective, this second poem rummages through a mixture of images of beauty and death (“rotting marigolds,” “sludge-gray” river waters “blossoming with saris,” a “bloated ox, stiff legs up, / slips by under sail”) and ends with the lines: “What corpse am I / scavenging for you?” The person addressed is the former husband.

Careless interrogation perhaps, but it becomes the catalyst that sets this book on its path. This insult summons the voice of the husband to challenge the narrator’s memory and aim: “You’re offering me a metaphor?” he asks.

The second voice, which Bolz says in the interview below “ambushed” her because it “wasn’t a conscious choice,” is a commanding presence in the book, at times refusing the narrator’s remembrances, reminding her that they “have other lives now,” and that she might not know what she is doing combing through their past. The unbidden voice of the living ghost (as it were) of the ex-lover propels Shadow Play into a multi-layered conversation between past and present, as it alternates poems in dialogue form with the narrative staple of the book’s beginning.

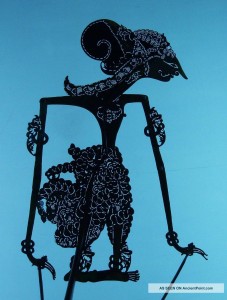

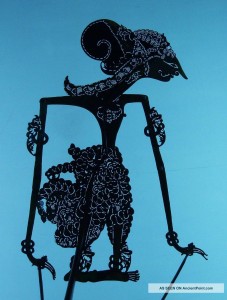

Artifice arguing with artifice, the made-up voice of the husband isn’t the narrator’s puppet. He is actively resistant, perceptive, and mature, so unlike the “giddy” boy he was in Asia. But he is still a voice, one the narrator has created, and acknowledges as a creation. Shadow Play is aware of itself, taking as its primary device wayang kulit, Indonesian shadow theatre, where puppets are manipulated behind a white screen on which their shadows are cast. As Shadow Play progresses, it becomes a kind of theatre, the narrator’s voice modulated and thrown in an effort to see “what’s true.”

Our story’s over

despite what we remember [the husband says]

So forget it—or revise it.

But what if it survives us?

Meditative and passionate, Shadow Play works its way toward an approximate answer to the question it opens with, a quotation from Roland Barthes: “How does a love end? —Then it does end?” For even in present day, happily married in Maryland, the narrator finds her heart in the East, longing to remember:

I turn away

from hearth and garden,

marriage bed and childbed—

I turn back

to lean over a map

of the country where I’m young,

my parents strong,

my luck untried.

I’m looking for a route

through time…

She retraces her past, falls deeper into memory, until returning to Asia:

Everywhere the terraced fields,

tropical and prosperous:

the moon is coming back,

rice is ripening.

But still the voice of the former husband won’t let her have her sweetest reminiscences, and often undercuts the beauty of her narratives: “How like you to contend with Time— / no challenge too absurd.” In denying her craft, he denies her philosophy. Indeed, by the middle of the book, he is drumming up scenes for their wayang, asking to revisit episodes from their year in Asia, and then asking her to speak of Ithaca, New York, where they met, and of other men and of the narrator’s betrayal. Invigorating and intricate, Shadow Play refreshes once again Sartre’s conclusion that “the order of the past is the order of heart.”

Although the proximity and urgency of two voices in Shadow Play dominate the text, to pay too much attention to their recitative dialogue would be at a loss of the music in the poems about Asia, lyrics that rise from the book with gorgeous images and insight:

I’ve never heard a sound

as sad and as sure,

though this is my voice

chanting for Shiva:

a big stone shape

enshrined at Prambanan.

Whoever carved the face

must have been surprised to see

how gracefully, implacably,

it registers each death

and stands accountable—

how smooth the lips and eyelids,

how lovely the look

of all that besets us.

Shadow Play ends with a poem originally published with the title “False Summit.” Yes, the book ends offering metaphor—“One minute we were climbing, / next minute we looked up // and the world had changed / ….another summit.” Carrying us close to the sky once more, the book’s attempts at reckoning ask us to recognize the lover’s discourse as the translated affair it is: a “trick of perspective,” light and shadow. A book of dreams, Shadow Play organizes itself within the wisdom of experience, knowing that despite impermanence and suffering, longings are what move us through our lives and how we remember.

—Jason DeYoung

.

Over the last few weeks, Jody Bolz and I exchanged a few emails regarding Shadow Play, its origins, its road to publication, and what compels us to read something that is imagined. Jody is a wise and generous poet, teacher, and editor, and her story of studying with A. R. Ammons and her insights on editing the poetry journal Poet Lore are not to be missed.

Jason DeYoung (JD) Can you talk about the origins of Shadow Play? It’s a very different sort of poetry book with a secondary voice coming on the scene to challenge the primary voice’s narrative authority.

Jody Bolz (JB) Years ago, I had a semester off from teaching college and was writing in the “quiet room” of the local library, hoping to draft some new poems. I began working on the opening pages of Shadow Play (a narrative about riding a night train in Java) without knowing that the poem was a point of entry into a book-length manuscript. What startled me was the way the poem opened out at the end into a broader view of a longer journey, both literal and psychological. I felt unsettled, as if I’d started to explore something beyond my reach.

In the days that followed, I wrote about another emblematic moment from that journey in Asia—an afternoon along the Hooghli River in Calcutta, during which a dead ox floated by with a vulture on its belly. Again, the poem made a sharp turn at the end, posing an emotionally charged question: “What corpse am I scavenging for you?” It was clear to me then that I was writing some kind of sequence—that the second poem had followed from the first, and that its ending demanded some kind of response. I didn’t know where I was going with any of this, but I was eager to find out.

The next day, something unforeseen (unforeseeable?) happened as I was writing in the library. Having revised the poem about the Hooghli River, I was struggling to move forward from its confrontational finale, and I turned the page and stared at it for a minute or two before writing a single line:

“You’re offering me a metaphor?”

It was a question in response to a question, a question in another voice. It ambushed me, which is to say it wasn’t a conscious choice. Is there such a thing as a subconscious choice? In any case, that was when I began to see how I might continue this exploration. I had no idea, then, that the manuscript I was starting would have two intertwined “through lines”—the arc of a narrative (the story of a journey in Asia) and the arc of an argument (the shadow dialogue between the two people who took that journey)—but I was all in.

JD: At your reading at Politics & Prose, you mentioned that you were working on this book before your previous book, A Lesson in Narrative Time, was published. Why do you think Shadow Play took longer to finish?

JB: It didn’t take very long to write, but it took forever to publish. I finished the first draft within six months, and after a year or two of revising, I felt ready to send it out. Without my knowledge, a couple of writers to whom I’d shown it nominated it for an award from the Rona Jaffe Foundation, and I was lucky enough to receive a grant. This was way back in 1998 (the last century…the last millennium, in fact!), and the recognition gave me hope the book would find its way into print.

I submitted it over and over in those early years, and though it was picked out a number of times in contests (as a semi-finalist or finalist) and often received encouraging comments from small-press publishers, no one said “yes.” Those who said “almost” praised the lyricism of the narrative portions but found the passages of dialogue baffling. One editor suggested I write a play instead. The general advice was: cut the dialogue, and then we’ll see.

By that time—well, maybe all along—I was committed to the book’s form. I saw it as integral to the story. Maybe the whole project was a failed experiment, but I wasn’t going to pull it apart. Writers I respected, novelists and poets alike, had found it inventive and engaging. They’d said it was the kind of book that teaches a reader how to read it. Disappointed that no publisher had taken it, though heartened that sections were appearing in literary magazines as stand-alone poems, I stopped sending it around. I wrote and published A Lesson in Narrative Time—another book-length sequence, but one without the genre-muddling issues that the Asia book presented.

In recent years I resurrected the manuscript, changed the typography a bit, gave it a new title (there had been three or four others), and put it in the mail again. When I discovered Turning Point Books, an imprint that focuses on narrative poetry, I thought it might be a good fit—and it was.

Hooghi River, India

Hooghi River, India

JD: The secondary voice in Shadow Play (which is a voice the narrator conjures) says at one point “this whole episode is pure pretense,” yet we keep reading, we keep reading this narrator who is essentially talking to herself about lost love. In one of your emails to me you wrote that “the notion of speaking ‘as if’ to the other person, while realizing you are talking to yourself, was significant.” Why is this significant?

JB: I think that’s the most important question one might ask about this book—or, perhaps, about literature in general. What compels us to read something that was merely imagined? In Writing the Australian Crawl, William Stafford talks about the nature of authority in poetry (as opposed to the nature of authority in the sciences, for example) and suggests that whatever authority you have as a poet “builds from the immediate performance, or it does not build.” If a line or an image or a posture feels false, we close the book.

From the earliest exchanges in Shadow Play, the reader knows the second speaker is a projection. He accuses the narrator of making him up, saying, “This voice is another trick” (she disagrees and calls it “artifice”)—but what matters is the authenticity of the argument, however internal. As the book progresses, the dialogue becomes more forceful and eventually dominates the story line. In a way, the shadow conversation enacts a partial answer to the book’s opening question: “How does a love end?”

If you’re asking why the ventriloquism is significant to me, I’d say it’s significant because it enabled me to write a book about the mystery of estrangement. It offered immediacy and intimacy while admitting that immediacy and intimacy no longer exist. A friend who’s studied Jungian psychology recently told me about the concept of “active imagination”—and from what I’ve read about the practice, it sounds like wide-awake dreaming in an effort to understand oneself or resolve problems. I think the imagined dialogue in Shadow Play has a kinship to that process.

A. R. Ammons

A. R. Ammons

JD: In every bio of yours I’ve read you mention that you studied with A. R. Ammons. He must have had a profound influence on your poetry (perhaps your life). Could you talk a little about his influence on you?

JB: I met Archie Ammons when I was a sophomore in college. If I hadn’t studied with him and learned from his example, I’m not sure how my writing life would have evolved. I’d always loved literature and had written poems and stories since childhood, but at 19 (in the Age of Aquarius…) I was open to so many things—and I might well have followed interests in other fields (anthropology, psychology). His relationship to poetry was something I responded to immediately. He didn’t posture, and he had no patience with those who did. He was an unconventional creative-writing teacher, more Zen master than editor-coach. He’d guide us by pointing us toward our best work, even if that meant nothing more than placing a check mark beside the one successful line in a poem. Archie taught by example, showing us what a life in poetry looked like—revealing its out-of-the-way beauty. To hear him read your poem aloud was an astonishing, and sometimes humbling, experience. He didn’t sing, of course, but his voice was melodic and slow and had a beguiling lilt (he was from North Carolina). You could hear what was right with the poem, and you could hear what was wrong. He always listened to us read our own poems aloud twice: first for the music and then for the meaning.

Late in my junior year, I began to find a few students in our workshop unbearable. I thought they were posing as world-weary geniuses though they were clearly rank beginners. I went to talk to Archie one afternoon to say I’d be missing class the next day, though I can’t remember whether I made an excuse or admitted I was going nuts and needed a break. In any case, he got the message. He spoke in general about teaching writing workshops and said he found it reassuring to view every poem—however weak, however false—as revealing of character and, in that sense, true. I wasn’t sure I understood the claim well enough to agree with it, but I stopped fretting about authenticity in the classroom and almost enjoyed regarding puffed-up poems as “true” expressions of phoniness.

I stayed on at Cornell for graduate school, and at some point during those two years, I began to feel I didn’t have the discipline or the drive to be a poet. I wondered out loud what it all meant (writing poems)—what it could mean to me in my life. He listened and nodded, but there was something in his demeanor, however gentle, that suggested I was over-complicating the question. And then he answered with a question of his own:

“Isn’t poetry just a matter of paying attention?”

I felt something shift in my chest. I knew he was using the idiom “paying attention” in a new way, and though I couldn’t take it all in at once, I recognized myself in its message. Being a poet wasn’t a career choice or even a choice. It was a way of being in the world.

JD: One of my favorite questions to ask writers is what is their definition of the “job” of writer, because they each have their own. What’s yours?

JB: What Ammons said about “paying attention” comes very close to my definition of the job. Writing, for me, is a way of moving through my own bafflement, of making connections and attempting to make sense of my experience—or, at least, to give my confusion a meaningful shape. Henry James wrote that a writer should be someone “on whom nothing is lost.” That’s the job description as I see it.

As I’ve often said in connection with my work as an editor of Poet Lore, poetry provides us with a record of human feeling, while history provides us with a record of events. Everything we’ve ever felt, everything we’ve loved and struggled to protect, everything that’s thrown us down or allowed us to recover will eventually be lost—but poetry can hold all of it and more.

JD: You co-edit Poet Lore with the poet and teacher E. Ethelbert Miller, and have been doing so for more than 12 years. How’s Poet Lore doing? And does editing a poetry magazine influence your own writing?

JB: Poet Lore’s doing well. Maybe someday we’ll manage to break even! No, really—our readership is growing steadily, and we’ve been receiving welcome attention recently as we celebrate the journal’s 125th anniversary in print. There was an article in The Writer’s Chronicle early in the year, and this spring book critic Ron Charles wrote a wonderful piece in The Washington Post about Poet Lore’s history and the challenges of editing a poetry journal. That kind of media interest has given us a big boost. And we’ve been encouraged by the many poets who’ve become ambassadors for the cause and are helping us spread the word.

I don’t know whether reading 1,000 yet-to-be-published poems each month, looking for the few we’ll take, has changed my own writing in terms of subject matter or style; but that discipline has given me a broader, deeper education about what’s possible in poetry. I’m a closer reader after 12 years as a journal editor—a more patient reader—and I feel lucky to have a role within in a community of engaged and engaging writers, hundreds of whom I’ve corresponded with over the years.

Ethelbert and I have joked that we’d probably reject our own work if it showed up on our desks—but it’s truer to say that we’re careful to read poem by poem, rather than poet by poet, and that we do our best to make choices without regard to reputation. We’re proud to have published many gifted young poets for the very first time. Among those is Reginald Dwayne Betts, who sent us poems while he was serving time in prison for a juvenile offense. How did we manage to pick him out? We read his work with the respect it deserved.

That sense of discovery keeps us going—as does our partnership as co-editors, which is an invigorating delight. Despite the necessary scut work (the copyediting and proofreading and subscription-pitching and fundraising), keeping Poet Lore going in its second century is a fascinating job—and I’m grateful to be doing it.

—Jody Bolz & Jason DeYoung

Jody Bolz was born in Washington, DC, and attended Cornell University, where she studied with A.R. Ammons. After receiving her MFA, she worked as a journalist for two major conservation organizations (The Wilderness Society and The Nature Conservancy) and taught creative writing for more than 20 years at George Washington University. Her poems have appeared widely in such magazines as The American Scholar, Indiana Review, North American Review, Ploughshares, Poetry East, Poetry Northwest, Prairie Schooner, and Southern Poetry Review—and in many literary anthologies. Among her honors is a Rona Jaffe Foundation writer’s award. She edits the journal Poet Lore, founded in 1889, and is the author of A Lesson in Narrative Time (Gihon Books, 2004).

Jason DeYoung lives in Atlanta, Georgia. His work has appeared in numerous literary journals, most recently in Corium, The Los Angles Review, TheNewerYork, New Orleans Review, Monkeybicycle, and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s Best American Mystery Stories 2012. He is a Senior Editor for Numéro Cinq Magazine.