Olzmann relies on a prosaic first-person style, rhyme-less, rhythm-less, too indifferent to metre to even be properly considered free verse. Many, many poets today employ a similar style. —Patrick O’Reilly

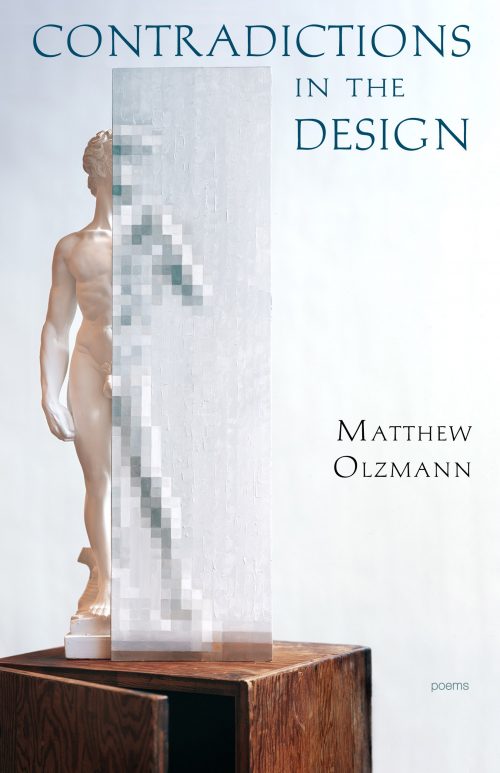

Contradictions in the Design

Matthew Olzmann

Alice James Books, 2016

100 pages, $15.95

.

Early in Matthew Olzmann’s latest collection of poetry, Contradictions in the Design, we are introduced to a young boy. For his birthday, the boy has been given a box of hand-me-down tools. “Immediately, he sets out to discover / how the world was made / by unmaking everything the world has made” (“Consider All The Things You’ve Known But Now Know Differently”, 9). The boy may serve as a stand-in for Olzmann himself, who excels at finding connections between the broken, the incomplete, and the obsolete, and who eyes every artificial thing with skepticism. As he claims in one interview, he is “the type of writer who understands the dark only by flicking the lights on and off a couple dozen times. I understand the deep end of the pool by splashing through the shallow side.”

With his award-winning debut Mezzanines (Alice James Books, 2013), the Michigan-born poet earned a reputation for his humour and accessibility, and his talent for juxtaposing seemingly incongruous images. Now residing in North Carolina, and armed with the confidence a well-received debut brings, Olzmann continues to explore his sometimes-jarring narrative style in Contradictions in the Design.

One stand-out poem is “The Millihelen”, named for “the amount of beauty that will launch exactly one ship.” Olzmann discovers such overlooked poetic sources with ease, and elaborates them masterfully. “The Millihelen” revisits the Trojan War, and considers a single ship leaving the entire fleet. Is this a ship carrying a disillusioned soldier away from the beachhead of Troy to a love he left behind? That’s not entirely clear, though it certainly seems that way. In any case, this ship is given more importance than the thousand Greek frigates sailing towards battle, a part bigger than the sum.

In “The Millihelen,” beauty is a destination. But that raises a possibility: perhaps this ship is the one which carries Paris and Helen away to Troy. That would be more consistent with the rest of the collection, where beauty and art are positioned as false virtues, traps which an audience could fall prey to. Certainly Paris’s own overly-enthusiastic pursuit of beauty had disastrous consequences.

The idea of beauty presents challenges for the artist as well. “Femur by mandible, I know what it means / to watch your good fortune change its mind,” Olzmann writes in “The Skull of an Unidentified Dinosaur”. That’s every poet’s pain, no doubt. But the poem itself depicts a dinosaur skeleton made up of mislabeled and mismanaged parts, the product of misguided creative labour, and exposes the blind faith and false assumptions required to not only appreciate, but to create art.

How Olzmann himself struggles for or against this artificial beauty is not always clear. There is little to suggest the kind of painstaking editing necessary to more intricate or experimental verse. Throughout, Olzmann relies on a prosaic first-person style, rhyme-less, rhythm-less, too indifferent to metre to even be properly considered free verse. Many, many poets today employ a similar style. What recommends Olzmann above them is the sense of cohesion in these poems: while most poets of a similar style still go in fear of literalness and overstatement, often to the point that their poems devolve into non-sequitur, Olzmann spares no effort to ensure that the reader follows every step of his associative process.

Olzmann’s talent lies not in his simple situational observations, but his observation of the whole metaphor, his observation of actors in a metaphor. He pursues the metaphor from its superficial meaning down to its pulp, showing the reader just where and why that metaphor is so poetically resonant. Think of him as a miner with a silver hammer, tapping the vein all the way to the motherlode. Oddly, Olzmann’s gift for drawing connections does not extend to other forms of comparative language. His similes, for instance, are usually duds: houses go “dark / like condemned buildings”, hair unfurls “like a flag”. These suit Olzmann’s unfussy, conversational style, but add nothing.

Olzmann is a noticer, rather than a craftsman. Coincidences and contradictions occur to him, and he draws them into the right perspective, but he never shapes them. This usually works. While not “formal poetry” in any traditional sense, nearly every poem in Contradictions in the Design operates under a particular formal apparatus wherein the poem is set up as a meditation on some single object or situation, then veers off in a completely unforeseeable direction, before returning to its thesis. This strategy, which I’m calling the “Olzmannian diversion,” makes it nearly impossible to quote from one of these poems and do justice to the whole poem, but it allows Olzmann to consider his subject from every angle, as though walking around a statue rather than merely looking at one face-on. As such, most poems in Contradictions in the Design have a satisfying sense of completeness.

Take, for example, “The Man Who Was Mistaken”, about a man who reconnects with his own sincerity thanks to a drug-addled roommate. The poem begins by mentioning the speaker is often mistaken for another professor at his university, who in turn is often mistaken for Moby, the electronica artist beloved by the speaker’s roommate. Then the turn:

Once he thought our furnace was talking to him.

Which is when I said, Why don’t you tell me

what the furnace was trying to say?

Which is when he said, It said

that me and it would always be enemies.

Which is when I said, Son, that’s a fight you can never win.

Which is when he said, Okay, and then went outside

to dance on the hood of his car.

Which is when the cops came.

Perhaps he was right. Jesus was inside the music.

And that music was inside my roommate.

And the state could not tolerate it.

I should note that this is just one small part of a long chain of events; “The Man Who Was Mistaken” follows Olzmann’s typical form: an opening gambit, a turn into shaggy dog territory, and then a return to the original theme in the third act, sort of like a sitcom. And the poem, already a page and a half long when this anecdote begins, goes on for another fifteen lines. The final line in the excerpt serves as that second turn, bringing the poem back to its original line of thought. While it acts as a punchline, dripping with false indignation toward “the Man,” it is also filled with genuine dismay that such harmless enthusiasm should lead to police intervention. The line rests precisely between the cynical and the sincere, which is where much of Olzmann’s best work happens.

But Olzmann’s competence can be its own trap. This is not a book one should read cover to cover. Taken at random, and with few exceptions, any one poem in this collection would be considered very good. The imagery is evocative, the humour charmingly ironic. But this one jarring, book-ended form would be more effective if used more sparingly. Reading Contradictions in the Design comes with a sense of degradation: inevitably some poems don’t seem to hit as hard as those which came before, and add nothing that earlier poems didn’t imply to greater effect. The Olzmannian diversion can lend a poem a sense of efficiency that it does not usually deserve.

This is a limitation to Olzmann’s style, as well. While the hyper-colloquial first-person narration affords him a degree of freedom not found in other poetry, it can also lead him to strain for importance. Such is the case with “Still Life With Heart Extracted From The Body Of A Horse” (16), a clearly personal, pointed poem, which devolves into bromides and clichés and eventually ends with a thud. When Olzmann gets political, as he does with this poem or “Imaginary Shotguns” (14), his politics are unthreateningly liberal[1], more bumper sticker than rallying cry.

What does one look for in a poetry? How can one define it? Olzmann himself might view even the question with suspicion. The poems which make up Contradictions in the Design are not challenging in any sense, but some might assert that “not challenging” is not necessarily the same as “not good.” I find myself, admittedly to my own surprise, in this camp. Olzmann draws insightful, even profound, connections between object and meaning. An artful poem, where several components work together in harmonious efficiency, such that you cannot replace a single mark for fear of breaking it, offers a kind of wonder. Here is a thing that shouldn’t exist, yet can’t possibly exist any other way, a made thing that feels innate. Olzmann’s poems are robbed of this wonder. But if the poems are without wonder, they still provide something like relief: that thing you noticed about the photocopier? Matthew Olzmann noticed, too, and he’s found some meaning in it that you hadn’t. Sometimes that’s enough.

—Patrick O’Reilly

N5

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

- Be advised: this is the opinion a Canadian critic. Issues like gun control and same-sex marriage, more or less settled here, may demand a less daring or incisive take in the United States.↵