Are there no longer any ants in Barcelona? Have they exterminated them all? Have they gone into hiding? Have they migrated to the suburbs?

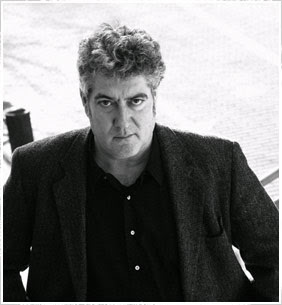

—Quim Monzo

A Thousand Morons

Quim Monzo

Translated by Peter Bush

111 Pages; $10.35

Open Letter

ISBN-13: 978-1-934824-41-2

The French philosopher Jean Baudrillard wrote that when we lose the relationship between the real and the map, between the referential thing and the simulation of it, we enter a strange, confusing space, something he called a second order simulacrum.“Today abstraction is no longer that of the map, the double, the mirror, or the concept. Simulation is no longer that of a territory, a referential being, or a substance. It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality; a hyperreal.”

Innovation and technology have brought abundant wealth and convenience into the world, but at what cost? We gorge on steady diets of advertising, steroid-fed athletes, and derivatives of something un-ironically called reality TV. (Even the joke is lost now, reality TV no longer being oxymoronic, perhaps only moronic). Our food is more abundant and readily available than ever, but it is also pre-processed and genetically modified. We connect instantly with friends and family across vast distances, but our online presence has robbed of us of privacy and silence.

Entire libraries of books can be carried around in our hip pockets, yet who has time to read? The ever-accelerating human narrative seems to be squeezing out nuance and complexity in favor of 140 character messages with hashtags and 3 million followers, but no actual person ever at the end of it all. Could Donald Barthelme have been right when he wrote that fragments were the only trustworthy form?

Surely we still need important voices crying out from the margins. The very best of our poets and writers always hover just inside Plato’s allegorical cave, somehow still able to witness and report that the culture of the hyperreal is an increasingly spurious one, not built from shadows of real beings dancing in front of the fire, but, more and more, from shadows of the shadows themselves.

The Catalan author Quim (pronounced “keem”) Monzo might well qualify as one of those voices. His fiction has been called surreal, hyperrealist, and highly original. He has written stories, novels, essays and translations throughout his long career, and he has worked as a journalist for various Barcelona newspapers. His brand-new-in-English story collection, A Thousand Morons, just published by Open Letter Books, wonderfully translated by Peter Bush, is filled with a dazzling lineup of stories, many of them awhirl in the transitional spaces between tradition and modernity.

Its characters and the places they inhabit are often nameless, shapeless, entities; many are merely pronouns, wandering through half-familiar territories. It might be one mark of the hyperreal world that proper names have become redundant: “The boy is walking down the street with a rucksack full of fliers hanging over his shoulder on a single strap and a roll of sticky tape in one hand.” Thus begins Monzo’s short story “The Boy and the Woman.” Does it matter what we call the boy? Have we all been likewise reduced in our over-crowded world? Even the slightly misanthropic title of Monzo’s book serves as a gentle (if playful) accusation, though it could’ve been more damning: Monzo could’ve titled it 7 Billion Morons and been done.

Written at the intersection of old and new, A Thousand Morons pulses with the current of time running through its sentences. In old age homes, mothers and fathers rot away and wish only for death. In refigured fairy tales, the prince rapes the sleeping maiden. There’s a certain madness about it all, with perverse gestures of love, misguided fools and ophthalmologists who can’t see. At every turn, absurdity and contradictions abound, as do humor, wit, and an enchanting spectacle of language. The sand shifts beneath your feet, and leaves you unsteady, shaken, wondering what it all means. The world is changing, Monzo seems to be saying, stand back and watch it with me.

In “Things Aren’t What They Used to Be,” Marta remembers her childhood, when, “though they had a television, her father, mother and nine siblings sat around the table at suppertime and nobody dreamed of asking for the television to be switched on.” Later, when she’s a mother herself, Marta regrets the way television has come to saturate her family life. Dinners pass in silence, her son and husband watching the news or Formula One races at the table. But before long, “Marta had begun to wax nostalgic even for those times, when she, her husband and their kid spent the night in front of the television.” The husband and father now lock themselves away with their computers, leaving Marta to miss the good old days when they at least occupied the same space, even one backlit by the television’s flickering blue lights. In two just two pages, Monzo creates an atmospheric tension about the rapidly changing world, making it humorous and heartbreaking at the same time.

But Quim Monzo is no Luddite; he’s not so much lamenting the passing of tradition as he is dissecting it and leaving its corpse on the table for us to examine. In some cases, he seems to willfully bid a fond farewell to the old ways. In “The Cut,” a boy enters a classroom with a gaping, bleeding wound in his neck. While he pleads with his teacher for help, the teacher upbraids the injured boy:

“Generally speaking, habits have been degenerating, and you are not to blame, I know. We are also to blame, in institutions that are unable to offer an education that shapes character with a proper sense of discipline and duty. But society is also to blame, and all the many parents who demand that school provides the authority they are incapable of wielding. You, Toni, are but a sample, a grain of sand from the interminable beach of universal disorder. Where is the discipline of yesteryear? Where are the sacrifice and effort? Where are the basics of education and civility we have inculcated into you day after day, from the moment you entered this institution?”

All these words while the blood pools around the boy’s feet. Absurdity abounds, past, present and future.

Monzo’s ability to reconfigure and challenge allows him to pack a literary punch with brutal efficiency. In the 150-word story “Next Month’s Blood,” the angel Gabriel visits the Virgin Mary and proclaims God’s intention to impregnate the young woman. But Mary refuses the holy annunciation: “’What do you mean no?’ asked the archangel at a loss. Mary didn’t backtrack: ‘No way. I don’t agree. I won’t have this son.’” Putting aside the humorous, contemporary dialogue between the two, the story reflects not only the changing role of women in the world, but the rejection of the hegemony of the Church, as well as some sort of weird empowerment and demystification of the Madonna, one of the most iconic figures in all of Spain.

A Thousand Morons is divided into two sections. The first section contains seven traditional length stories, and the second is made up of twelve shorter stories, what might be called ‘flash fiction’ pieces, some less than a page in length. Throughout both sections, Monzo interrogates the changing landscape of storytelling itself.

In “Thirty Lines,” an unnamed narrator explores how to tell a story using only thirty lines of prose. “It’s like asking a marathon runner to run a hundred meters with dignity,” the narrator says, even as he writes. But by the end, he accomplishes this ungainly task of compression, and the narrator (and presumably Monzo behind him) defeats the assignment by turning the task against itself:

He has only seven to go to reach thirty. But, after he has registered that insight—plus this one—even less remain: six. Good God! He is incapable of having a thought and not typing it, so each new one eats up a new line and that means by line twenty-six he realizes he is only four lines from the end and hasn’t succeeded in focusing the story, perhaps because—and he has suspected this for a long time—he has nothing to say, and although he manages to hide this fact by dint of writing pages and yet more pages, this damned short story makes it quite clear, and explains why he sighs when he reaches line twenty-nine and, with a not entirely justified feeling of failure, puts the final stop on the thirtieth.

Monzo’s spare prose leaves little room for context. Explanations and motivations remain elusive. Yet there are echoes of wisdom, and the absurd becomes more than just whimsical commentary on the world. In the opening story, “Mr. Beneset,” Mr. Beneset’s son arrives at an old age home to visit his ailing father. He walks into the room only to discover his father putting on “black and cream lingerie, the sort the French call culottes and the English French knickers.” What’s most startling about this set up is that Monzo provides no details, no clues to the reasons for what’s happening. We don’t know if the father has simply lost his mind or if he’s been cross-dressing his whole life. The son makes no comment about the odd behavior. Mr. Beneset puts on tights, a skirt, applies his makeup and then heads out to the backyard where the other residents of the old age house “gawp vacantly” at the two men.

But perhaps the quiet wisdom of the story rests on the way love is offered without stipulation, even while the other residents gape at the strange old man. At the end of the visit, as Mr. Beneset and his son say their goodbyes, “they kiss each other, the son turns around, walks away, stops by the door, turns around, waves goodbye to his father, closes the door and uses the handkerchief to remove the lipstick the kiss left on his cheek.” Is this not a nearly perfect example of love?

By toying with expectations, by working against logic, Monzo creates sharp instabilities in his stories. We are enchanted, confused, even a bit angry at ourselves for not understanding. At times, we can’t help but wonder if we have suddenly become one of the thousand morons.

If there is a shortcoming to this book, it’s that Monzo’s characters often feel overly disembodied. There’s a frigidness about them, a parchment paper quality that makes them dry and brittle. It’s hard to feel compassion or empathy, but then again, that might be exactly the point. Monzo’s characters reflect the contemporary zeitgeist, an age when men and women will drive by and honk if your car breaks down on the side of the road. But their derision is not borne out of cruelty so much as it is out of conviction of certainty about their world. They wish you no harm as you stand there on the side of the road waiting for help; they simply expect you’ll have a cell phone and already have called for a tow truck.

Almost fifty years ago, John Barth wrote about the literature of exhaustion. Today, we flirt not just with exhausted literature, but with the literature of the comatose, the persistent vegetative state that is becoming our civilization, dominated by media moguls peddling pop culture, best sellers and Pepsi Cola across vast, global landscapes with little regard for anything besides profitability. A Thousand Morons was originally published in 1997, just as the twenty-first century was about to dawn, as the new millenium’s Everyman was about to rise from his bed, stretch his arms and head off for work. Except he wasn’t a man anymore, he was an IP address, and he wasn’t heading for the office, but for the local Starbucks, and whether he was in Mumbai or Manhattan, Cairo or Kuala Lumpur, the menu remained the same (and in English). He ordered his venti frappuccino — words themselves now part of the hyperreal lexicon — sat down at his wireless hot spot and connected to the world. Except he couldn’t connect to anyone real, only to a host of other disembodied, genderless abstractions, avatars lost in cyberspace, that ever- accelerating multiverse of 4G networks, pre-packaged apps and unlimited texting.

Monzo indicts us all, participants in our own demise, as we drift further and further away from the things which anchor us to the ground. We are being crowded out, Monzo says, most poignantly in “Shiatsu” the final story in the collection “It’s a great bar,” the story opens, “a favorite in the neighborhood, with maybe the finest ham in Barcelona, and hocks—done in the oven with onion, tomato, pepper, white wine, and cognac—of the highest quality.” Three men are enjoying breakfast at the bar, until they forced to leave by a crowd of newcomers. These loud, jovial people appear to be outsiders. Under their arms, they carry (ironically) folders from the “Institute for traditional Chinese medicine.” One by one, the original three men in the café give up their seats and are squeezed out by these newcomers, until only one of the original three remains. The newcomers (for some reason, I picture them as hipsters, in skinny jeans and carrying the latest version of the latest smartphone) are eyeing this last man’s table, hoping he’ll leave too. He endures for a while, but they are bumping past him at the bar:

But soon the accidental knocks become deliberate and increasingly outrageous, and so they pile on the pressure—now he hears them pushing to shouts of ‘Come on, altogether,: wow, wow, wow!’—he gets up and pays. As he is going into the street to the gleeful victory cries of the throng inside, he has to move aside yet again because three more individuals sweep in with their folders from the institute for traditional Chinese medicine, masters now of the whole of that bar they have finally succeeded in making their very own.

How odd that the men in the bar yield to the crowd so passively. How quickly they are replaced and vanquished, though perhaps this has always been the way. Out with the old, so the saying goes.

In Barcelona, where ham cures on the hook above the bar, ordering a plate of jamon y queso means that the diner sits just inches from the kneecap of the sacrificed animal. Try putting a meat grinder in the deli aisle of your local Trader Joe’s and see how quickly the store empties out. It’s not that Monzo possesses some exotic birthright which helps him stay in better touch with the world. He simply understands the clash between the real and the simulacrum, and is thus able to dramatize it in his stories. Monzo reminds us that there is a cost to all this change, and if contemporary culture represents a buffet table for the hyperrealist, then A Thousand Morons is like a literary tapas bar, offering up its small plates with distinctive flavors, but hardly enough to fill the belly.

Perhaps it helps that Monzo is homeported in a place where cultures and languages collide. Barcelona: The city where the writer can probe the battle between tradition and change right there in the streets. Barcelona: Where Gaudi’s surreal cathedral, La Sagrada Familia, rises out of a modern skyline like some twisted anachronism, half-old, half-new, the church still under construction some hundred and forty years after it began. Barcelona: The dreamscape city, an amalgam of the real and the hyperreal, of fiction and truth.

Monzo’s strange delicacies reflect the geography and history of the city itself as much as they do the plight of contemporary humanity, full of absurdity and humor, heartbreak and despair, and, in the end, full, too, of beauty.

Richard Farrell earned my B.S. in History at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis and an M.F.A. at Vermont College of Fine Arts. He is a Senior Editor at Numéro Cinq and the Non-Fiction Editor at upstreet. In 2011, his essay, “Accidental Pugilism” was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. His work has appeared in Hunger Mountain, Numéro Cinq, and A Year In Ink. He is a full-time freelance writer, editor and a faculty member at the River Pretty Writers Workshop in Tecumseh, MO. He lives in San Diego, CA with his wife and two children.

Until Charles Foran’s recent Mordecai: The Life and Times, the various biographies of Mordecai Richler suggest that an interesting subject for biography does not necessarily an interesting biography make. Great lives don’t always inspire great books. In the decade since Richler’s death in 2001, four books entered a biography’s race between early market share, thoroughness and accuracy. Globe and Mail journalist Michael Posner pre-excused the scattershot tone of his 2004

Until Charles Foran’s recent Mordecai: The Life and Times, the various biographies of Mordecai Richler suggest that an interesting subject for biography does not necessarily an interesting biography make. Great lives don’t always inspire great books. In the decade since Richler’s death in 2001, four books entered a biography’s race between early market share, thoroughness and accuracy. Globe and Mail journalist Michael Posner pre-excused the scattershot tone of his 2004