15th Cen. St. Brenden & The Stranded Whale, British Museum

15th Cen. St. Brenden & The Stranded Whale, British Museum

.

There shines in us, though dimly in darkness, the life and the light

of man, a light which does not come from us, which however is in

us, and we must therefore find it within us.

Gerhard Dorn – Philosophia specuativa

.

“As the dead prey upon us,

they are the dead in ourselves,

awake, my sleeping ones, I cry out to you,

disentangle the nets of being!”

Charles Olson

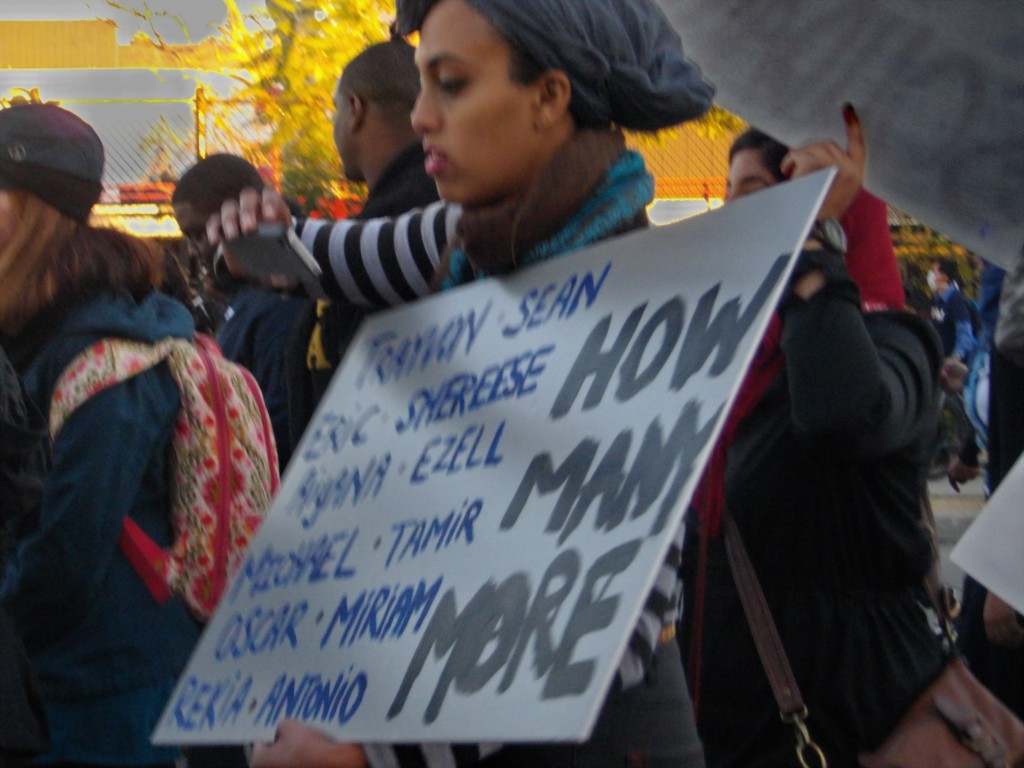

1 – Pedrolino

WOKE THIS MORNING in the house where the poet Vincent Ferrini lived and wrote for decades, now the Gloucester Writers Center.August 17th, 2014, at 7:30 AM, newly risen light washes purple drawstring shades, which I keep half-shut. Perched on the shoulder of East Maine Street, a two lane coastal road that runs between downtown Gloucester and Rocky Neck, traffic up and down the hill sets up a constant rush of sound. The front door opens on a gas station/ convenience store at the far side of a parking lot. In back workmen level ground to pave a narrow alley. People walk close to the windows. There’s a small kitchen at one end, and a bathroom off the main room. I’ll be the poet-in-residence here for a week, which ends with a reading from my latest collection, Fishing On The Pole Star.

Last night, after a chicken/vegetable stir-fry dinner, I turned on the overhead fan, moved a lamp to the side of the vintage pull-out bed and perused a book case lining the wall stacked with copies of Vincent’s collection, Know Fish. Among them I found a copy of Charles Olsen’s Collected Works and fell asleep reading his signature poem, “The Kingfishers.” This morning I dimly remember a dream in which I’m standing in a rowboat fishing from the stern with a child’s rig. I understand the implication that I am still developing as a fisherman, but have no doubt that knowing fish has brought me here.

Framed poems hang on white walls beside images of Ferrini and his friend, larger than life poet Charles Olson, who mythologized Gloucester as Joyce did Dublin. Standing 6’8”, aka Maximus, and former rector of Black Mountain College, Olson played a major role in the dynamic changes that drove mid-20th Century American poetry. Ferrini appears small beside him, but no less haunting.

Vincent Ferrini, (monoprint) by Jain Tarnower @ The Gloucester Writers Center

Vincent Ferrini, (monoprint) by Jain Tarnower @ The Gloucester Writers Center

I work on a table facing a print of Ferrini outlined in white on a black field—an image dominated by his white face and hands. He wears a domed hat, like a novitiate in an obscure Italian order, but might as easily be Pedrolino, the moon-faced dreamer out of the comedia dell’arte. His smile is enigmatic. It reads like a confidence, an intimate whisper in my ear: Pay no attention to what is going on outside and around you. Do as I did. Listen for what comes through the inner doors and windows.

I follow the instruction, submit to the inner sensorium.

What enters is as much shape as sound, ideas like iron filings on a magnetic field. The field becomes an ocean, the magnet a star. Fish swim below or break the surface. Constellations in space dance without touching. This ghost in the room I think of as Pedrolino has awakened a ghost in me. I see myself standing beside Amfortas, the Fisher King, in the Pole Star watching a king fisher dive. How did Amfortas end up in my boat, both of us in the stern waiting for Parzival or his equivalent? Olson’s poem, “King Fishers,” which influenced me as a young poet, has set up an inexorable call to the obsession of my later years, the wounded Fisher King!

Amfortas drops his line next to mine, and with it the orderly content of my inner world breaks down. I can’t predict what will emerge from this matrix, what looks like a massa confusa, but is possibly the first stage of important work.

Pedrolino nods.

“Yes,” I tell him. “I accept.”

I’ll take the risk, go where the currents lead. I am a navigator with faulty maps and a ragged compass. But there is a mystery on the tip of my tongue waiting to be revealed, a series of linkages I had not suspected before that will pull valuable information out of the shadows into the light of day—if only I will engage the journey.

Pedrolino is pleased. His smile deepens.

I let him know that in addition to my reading I will give a talk, because the title just popped into my head like a mackerel: “Trolling With The Fisher King.”

That is, after all, what this about. Whether alone in the boat, or with Amfortas trailing in Charles Olson’s wake, fishing is what connects us. It is as though now all three of us were working the same line after the catch we were all hoping for—the wisdom that whispers, “What wounded thee will make thee whole.”

I email my host Henry, old Ferrini’s nephew, proposing the talk and its title and suggest it immediately follow my reading.

Almost instantly, I get a reply: “You’re on!”

Pedrolino likes this.

.

2 – Spreading the Net

The Fisher King figure in its present form appears prominently in Wolfram von Eschenbach’s 13th Century epic, Parzival, set in a landscape devastated by war. Armies returning from the Crusades, and mercenaries hired by expansionist nation-states, have pillaged the countryside. Against this backdrop, knights governed by the archaic laws of chivalry kill each other in the name of love and honor, leaving a trail of widows and fatherless children in their wake. Parzival’s mother, stricken by the loss of her heroic husband, takes their son into the woods vowing he will not perish in this way. She raises Parzival in a state of nature ignorant of his lineage and his real name, which means piercing through. One day at an age when most young men leave home, he sees a brace of knights in armor riding through the woods and mistakes them in their shining armor for gods. Parzival follows them to King Arthur’s court, where he gains entry by killing the Red Knight who blocks the entrance with a lucky throw of his lance through the eye-slit in the seasoned warrior’s helmet. Still innocent (unconscious) but triumphant, the fledgling sets out to prove himself, and becomes what his mother feared most, a man who kills in the name of love and honor.

Riding past a lake one evening at dusk Parzival spies a man fishing from a dingy who directs him to a castle where he can spend the night. He doesn’t recognize that the fisherman is Amfortas (without strength), keeper of the Grail. Under the banner of AMOR, Amfortas killed a Saracen warrior in single combat, and ever since that time has carried a piece of the Infidel’s lance in his groin. Because his pain is greatest in the presence of the Grail, Amfortas can no longer function as Grail Keeper. He now sits with a line in the water to ease his pain waiting for one pure in heart to ask the question that heals his wound, and restore the Waste Land.

In some versions, the question is, “Whom does the Grail serve?” in others, “What ails thee?”

The innocent (unconscious) Parzival doesn’t recognize himself as the one for whom Amfortas and all attendant on the Grail are waiting.He follows directions to the Castle and is welcomed by attendants who bathe and dress him. In the Great Hall he witnesses the procession of the Grail that once held Christ’s blood, and the lance used by the Roman soldier Longinus to pierce His side. Joseph of Arimathea, who prepared Jesus for burial was said to have brought these sacred objects to England.

Galahad, Bors, and Percival achieve the Grail. Tapestry woven by Morris & Co.. Wool and silk on cotton warp, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

Galahad, Bors, and Percival achieve the Grail. Tapestry woven by Morris & Co.. Wool and silk on cotton warp, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

From his divan in the Great Hall, Parzival watches robed acolytes parade with the spear that pierced Christ’s side. After this another set of acolytes carry the Grail, which fills the tankards, bowls, goblets, trenchers, platters and baskets with all manner of delicacies, from fowl, and mutton to cheeses, fruits, breads and wine until everyone at the banquet is provided for. There appears to be no limit to what nourishment the Grail can bestow. In the right hands, such abundance might feed the world.Seated across from him Amfortas writhes in pain waiting to hear the question that will deliver him. But Parzival has been taught that it’s impolite for a guest to question his host, and so he fails to ask the question. He wakes next morning to find the Castle empty except for spectral voices jeering from the battlements. The drawbridge slams shut behind him. Slowly, it dawns on Parzival that he has failed to recognize this opportunity.

It’s a bitter pill.

All of his assumptions, the received wisdom given by those in authority, dissolve in the first light of consciousness. He will spend the next twenty years wrestling with this failure. In the end, confronting his own wounded pride, he is able to “pierce through” to the recognition of his true identity as heir in that lineage as Grail Keeper.

Two details must be noted: after recognizing his role, Parzival rejoins his wife in true union, a Holy Marriage (heiros gamos); and, finally, he encounters his dark brother, Fierfize, (piebald), the son their father, Gahmuret, sired with the black Moorish Queen Belcane, in the North African Kingdom of Zazamanc, on his way home from the Crusades. Concealed by their armor, they face off without knowing the identity of the other. Just before delivering the death blow Parzival sees his brother’s face free of the helmet, recognizes him, and the once embattled knights embrace.It begins as a reprise of the battle in which Amfortas was wounded, and ends with a resolution. Parzival welcomes his dark Muslim brother as a part of himself. He can heal the wounded Fisher King by asking the question which he now embodies. Amfortas, free from pain, dies in peace. may be a cipher and a prescription for our own time..

.

3- Mare Nostrum

The reading at the Gloucester Center for Writing from Fishing On The Polestar is scheduled for later this week. The poems record my experience trolling the out islands of the Bahamas, exploring obscure inlets, crossing the section between Eleuthera and Columbus Point known as “the tongue of the ocean.”

What would the tongue of the ocean say if it could speak?

I recall last night’s dream, and reel it up from my store of memories.

As a child I hooked crappies (small sunfish) in Prospect Park. In the 70s , I hauled in snapper on a hand-line from a dugout off the coast of Belize. Later, I trolled for bill fish in a 42’ Bertram from Ft. Lauderdale to Crooked Island. In time it dawned on me that as a poet and psychotherapist drawn to the unconscious, my lures were set to bring up something concealed in my own depths. I have come to understand the Fisher King wound and why a line in the water brings relief.

Olson’s Collected Works lies on my bed open to “The Kingfishers”. I read: What does not change / is the will to change…

He woke, fully clothed, in his bed. He

Remembered only one thing, the birds, how

When he came in, he had gone around the rooms

And got them back into their cage, the green one first,

She with the bad leg, and then the blue,

The one they had hoped was a male.

Since the poem was published in 1949, no one has been able to give “The Kingfishers” a definitive reading. Those who engage it are drawn or repelled; few are indifferent to its movement. Some critics call it a dreamscape, and there is reason to treat it as such. Others cite it primarily as a response to post-Holocaust trauma.But what’s most haunting about it is less historical than psychological. “The Kingfishers” occupies a limbic space, that threshold between sleeping and waking where the conscious and unconscious are open to each other. This is also where we locate the Grail Castle that appears and disappears, a quantum space beyond fixed coordinates. Here, Charles Olson drops his lures.

Dialogue at Five (Provincetown) – Herman Maril

Dialogue at Five (Provincetown) – Herman Maril

Lines from “The Kingfishers” float through dream-time into morning light trailing brightly colored green and blue feathers from two caged birds. Still in bed, I hear seagulls outside squawk and cry. Sea-birds have trailed in my wake for hundreds of miles, like my golondrina. As a merchant seaman crossing the Pacific I watched a tiny swallow hitch a ride from the Golden Gate to Subic Bay on our United Fruit ship. Even through the roughest storms. When I thought it had been blown away, there it was the next morning perched on a boom. Long after I returned from the South China Sea, the swallow haunts me. Like Olson’s kingfishers, my golondrina, exists as an ache in the present—an unhealed wound.

I follow my ghost bird into the poem.

Neither “The Kingfishers” nor the Fisher King is primarily concerned with the act of fishing, but each links deeply wounded cultures, lacking coherence, to fishermen, fish and fishing birds. A lost but crucial piece of psyche must be restored. I fish for the clue in Olson’s paradox: everything changes but the will to change.

What is the lure attached to this line?

Wayne Atherton – Mounting The Bounty

Wayne Atherton – Mounting The Bounty

It isn’t change that carries the charge, but the “changeless will,” and what that implies.We are drawn to what is concealed in changeless will. Calculations will not reveal it. Otherwise discourse—words, ideas and numbers alone would heal the Fisher King wound.Better to follow the kingfisher into limbic space, watch it circle, dive, and emerge with a fish in its beak. Reason will not tell us what lies beyond it, like the sublime—or how to locate “changeless will” in the wound, the fisherman, or the fish.

Better to follow a ghost bird.

.

4 – Fixing the Colors

Olson’s narrator wakes fully clothed from a dream. Seated at my computer, under Pedrolino’s watchful eye, I recall that seabirds following a school will mirror the behavior of the fish, then feel a tug, rock back and forth as if I were in the fighting chair. What I bring to light surprises me, a dream fragment from last night. I enter a room where people dressed in blue and green are waiting to hear my talk, “Trolling with the Fisher King”. Olson’s birds are blue and green. This is not insignificant. He quotes 16th Century Belgian alchemist/psychologist Gerhard Dorn: “Color/ is the evidence of truth.”

I agree. Color is important.

As an eight-year-old fishing for crappies in Prospect Park, I watch my cork bob on a bed of light that splinters when the float sinks. As I reel in a sunfish, brightness falls from the air (a line James Joyce borrowed from Thomas Nash). The brilliance of its scales fires my imagination. These sparks are evidence of an underwater rainbow I might pull up whole as all those other kids marvel. It will give me super powers, change my life by calling forth the power inside of me.

Years later, at sixteen, reading Freud’s Future of an Illusion, I understand that fishing my dreams is more likely to yield that life-changing catch. The flashes of color I glimpsed as a child were aspects of myself yet to be identified.I’m still waiting for a vision to break the surface like a marlin.

“Color…fixes the statement,” (Olson via Dorn).

What shall I say about “The Kingfishers” to my dream audience in kingfisher colors?

“We trail lines defined by the color of our lures.”

Sun, Arthur Dove, the Smithsonian

Sun, Arthur Dove, the Smithsonian

The first thing Olson does in “The Kingfishers” is to pluck color from dream-water, the green female bird “with the bad leg,” and the blue male returned to their cage by someone named Fernand who “ had talked lispingly of Albers & Angkor Vat,” and subsequently leaves the party that is taking place…

When I saw him he was at the door, but it did not matter,

he was already sliding along the wall of the night, losing

himself

in some crack of the ruins. That it should have been he

who said, “The Kingfishers!

who cares

for their feathers

now?”

Fernand dissolves like a shadow in “some crack of the ruins.” He points to what we otherwise can’t see, and seeing, turn away. No wonder the poet regrets that it should have been Fernand who poses the question: who cares? The shadow’s voice, peripheral to awareness,delivers a message that draws us down, even as it hangs in the air like an accusation. The poet wishes the question had been his to ask.

Parzival also begs the question; the part of him that would ask it remains buried in his split-off shadow. He must become fully conscious to ask the healing question: What ails thee?

Fernand’s question points to, rather than discloses the disconnection, and so rings both as desperate and ironic: Who cares?

Outraged, Olson raises a more pressing question: Who is Fernand anyway, this shadow that speaks what must be said, then vanishes, leaving behind him a cloud of regret? Fernand’s question, “Who cares?” exists as a statement yet to be understood by those at the party, including the poet.This Post-Parzival situation finds us in stagnant waters.

Bright blue and green sparks in the kingfisher feathers at the opening of the poem disappear into the rapidly deteriorating natural world. Observing from the shadow’s point of view, Fernand comments.

His last words had been, “The pool is slime.” Suddenly everyone,

ceasing their talk, sat in a row around him, watched

they did not so much hear, or pay attention, they

wondered, looked at each other, smirked, but listened,

he repeated and repeated, could not go beyond his thought

“The pool the kingfisher’ feathers were wealth why

Did the export stop?”

Those at the gathering are confronted with the degraded pool at their center, evidence of unconsciousness. They are unmoved, look but don’t see, listen but don’t hear—remain in a peculiar state of indifference, partying in a Waste Land. Part one of “The King Fishers” ends here, with Fernand’s unanswered question.

It was then he left.

.

5 – Consciousness / The Wound

How did we become deaf to the voice that reminds us to wake up? Mother earth calls from the depths, warns us to pay attention. This was the purpose of the Great Mysteries. The Dying and Reviving Gods like Tammuz, Dionysus, Attis, Adonis, Ba’al and Jesus demand we remain conscious. Their myths and ceremonies of wounding and healing model the birth, death and resurrection of consciousness, a transformative experience open to those who understand it. In her study The Language of the Goddess (1989), Marija Gimbutas points out that wine and bread were revered as sacraments in Neolithic cultures because they represented the inherent potential for transformation produced by fermentation and yeast. Early Egyptians drank beer and tasted Osiris wafers to partake of an eternal blood and body. The Pyramid Text, dating back to the 5th Dynasty (2,400 BCE), instructs the king to rise from his tomb

Take your head, collect your bones,

Gather your limbs, shake the earth from your flesh!

Take your bread that rots not, your beer that sours not…

The same text, perhaps the world’s earliest known religious document, records the worship of Osiris, Egyptian lord of the Underworld. Depicted with green skin, a pharaonic beard and ostrich feathers on either side of a conical crown in later hieroglyphs, Osiris is the poster boy for death and resurrection. Dismembered by his jealous brother, Seth, and re/membered by his sister/wife, Isis, Osiris knits worlds above and below into a seamless whole, just as the wounded Fisher King embodies the potential to restore the Waste Land. But there is a shift in this mythos between Dynasty V and the 12 Century AD, and again into our Post-Internet culture. The drama is no longer the provenance of the Gods. The transformation requires human participation. Parzival must become conscious of his own wound before he can heal Amfortas and accomplish his mission.

We are dealing in symbolic terms with human development, the ordeal through which split off material in the unconscious is brought to light and integrated. Carl Jung found in Alchemy a compelling description of transformation applicable to the totality of the psyche. For him, the writing of adepts like Gerhard Dorn revealed in symbolic language the relationship of the unconscious to the conscious as the agent of psychological transformation. Jung recognized in Alchemy an intuitive iteration of Psyche’s drive to realize itself. Olson also quotes Dorn suggestively: “Color is important.”

The Alchemical Work broadly speaking unfolds in four stages, the first of which is a condition of decay, the “blackening” known to practitioners as nigredo. It is analogous to the initial wounding, the early call of the unconscious to become conscious. Olson’s poem locates it in Fernand’s recognition of the pool become slime. He points it out to those gathered but no one hears him. Only when there is some acknowledgment of the condition can the Work move on to stages known by their colors, white, yellow and the reddening, rubedo. Here, the transformation is realized in the body of the “Philosopher’s Stone”, or as Parzival beholds it, the lapis exilies, another name for The Holy Grail.

Olson’s poem can be read as the search for materials in anticipation of the Alchemical Work, which is increasingly difficult as we are blinded by distractions. Psyche’s drive toward transformation, the hidden telos in Olson’s “will to change,” calls out to us. His poem, “The King Fishers” is an attempt to hear it, a plea for us to open our ears or suffer the consequences. Riding the stern of his work, feathered lures in the water, I see Charles Olson become the Fisher King. It’s not the nigredo alone he fears, but that he (we) will get stuck in it, and stay that way—trapped in

a state between

the origin and

the end, between

birth and the beginning of

another fetid nest

Phylogeny recapitulates ontogeny: the principle states that each of us in our development recapitulates the evolution of the species, and possibly the entire universe, from chaos to cosmos. If true, there is a moment when that movement becomes conscious of itself, a shift (or fall) from undifferentiated “time before time” into time as we experience it—antiphonal, polarized, and fleeting. In a number of myths, the creation of cosmos from chaos involves horrific violence, a wounding and dismembering that becomes embedded in nature.

For the Aztecs creation begins with a many armed female monster, a hungry mouth at the juncture of each arm. In this myth, the agents of “the will to change”, Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca, become serpents, wrap themselves around the insatiable matrix and twist until she comes apart. From her parts they construct the ordered world which remembers the pain and exacts tribute in blood. Sumerian hero-god Marduk does the same to the complaining sea-serpent Ti’amat. The mother of us all, pre-conscious chaos incarnate, must be torn apart. This process, essential to creating and sustaining order, also produces the consciousness that re/members that pain.

The wound requires appeasing. Host cultures enacted blood rituals of reparation to a matrix that might exact revenge if disregarded. If we forget or cease to feel the pain inherent in becoming conscious, degradation of the psychological and natural worlds follow as surely as slime on the pool. Numbed and disconnected, we dismiss Fernand’s warning, whisperings from the shadow in the wings.

Kingfisher hovering, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

Kingfisher hovering, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

.

6 – Re/member Me

In Greek mythology the wind god, Aeolus, intervenes when his daughter Halcyon attempts to follow her mortal husband drowns in a storm. Aeolus prevails on Zeus to turn them into birds. Zeus does this, but requires that she nest on the shore for two weeks in mid-January ever year during which he stays the waves and winds to let her young hatch in safety. These become known as Halcyon Days; we know these birds as kingfishers.

It is true, it does nest with the opening year, but not on the waters.

It nests at the end of a tunnel bored by itself in a bank. There,

six or eight white and translucent eggs are laid, on fishbones

not on bare clay, on bones thrown up in pellets by the birds.

I have observed riverine kingfishers nesting in the muddy banks of the Sibun River in Belize. We steered our canoe through an uncharted stretch that flowed between the Pine Ridge and jungle low-lands. I noted anhinga, heron, hummingbird and toucan—among other exotic avian life—but the kingfishers where most memorable. They darted in and out of tunnels in which they built their nests. I think of them as I read Olson’s description of that process, how they construct those nests of decomposed fish bones—evidence of which was visible and odiferous as I passed them on the river bank.

Mostly it was the sea-birds I followed.

Hieroglyph Swallow, a.frostly.com

Hieroglyph Swallow, a.frostly.com

E.H. Gombrich tells us in his Little History of the World: “If you want to know where Egypt is, I suggest you ask a swallow.” That’s where they fly every autumn, over the Alps to Italy, across the sea, to the Nile valley. My golondrina: the swallow, for centuries the talisman of seamen—square riggers manned by seamen with barn swallow tattoos on their arms and chests. The swallow delivered a lost sailor’s soul safely to the Underworld. A Pharaoh tells us in the Pyramid Texts he has “gone to the great island in the midst of the Field of Offerings on which the swallow gods alight; the swallows are the imperishable stars.”

Poems in my book, Fishing On The Pole Star, describe birds circling or diving into weeds banked on shoals where small fish are feeding, larger ones under them, and at the bottom tier great creatures with silver fins that break the surface, incarnate beams of light. Aloft on the tuna tower of our boat, a small seat on top of a ten foot ladder rising from our bridge, I admired the weave of worlds from Bimini to the Planas. For years the sun drenched waters appeared to be as they had always been. Then the veil fell from my eyes. I’d been like those Fernand addressed at the pool-party, unaware of the slime.

The Waste Land referred to in Parzival, and revived as a theme by T.S. Eliot, links the mythic to the ecological narrative. The state of the physical world is a reflection of the psychological one in which we live. Our willingness to read and understand it depends on our ability to tolerate the pain in that recognition, and our desire to heal it.

Changes in Bahamian and Caribbean waters have been incremental, but can be measured in bleached reefs, diminishing schools of tuna, the paucity of local catch, and marlin moving further south to Piñas Bay. Sea birds—cormorant, frigate, pelican, heron, and kingfisher—that dive with satellite precision, are the unifying connection of above to below. What becomes of them as the fish populations dwindle? “Who cares for their feathers now?”

Changes in temperature provide a breeding ground for stinging mites that make it impossible to swim in certain locations without a wet suit.

Cays with white sand beaches that held no footprint are now virtual stages where Bahamians set up a fake village for Holland American Line cruise ships, where tourists buy folk art, drink rum punch, and dance to a reggae band before cruising on, unaware they’ve been in Disneyland. It might’ve been a protected beach for halcyon birds to hatch their eggs, but who can protect them from cruise ships?

We’ve come a long way from the Pharaoh’s great island tenanted by imperishable sparrows. All assumptions about endlessly resilient Mother Nature are no longer tenable. NASA photos reveal we live on a frangible sphere wrapped in atmospheric lace. We are now cognizant of five previous extinctions.

Where does the extinction of our species fit in?

In addition to species, we are also aware that words and feelings can become extinct, the once rich chords on the emotional scale reduced to simple notes. Awe, a word once a referring to a transformative experience, has been reduced to a trivial response in every day speech.

What happens to us, and to the natural world when we remain unconscious and therefore unable to address the wound?

Olson puts it another way: What happens when only the feathers are left?

Tomb of Nebamun, Thebes, ca. 1350 BC, British Museum

Tomb of Nebamun, Thebes, ca. 1350 BC, British Museum

.

7 – Focusing on the Feathers

Olson’s emphasis on the bird and its feathers makes me think of ancient Egypt. In the Ur-myth Isis re/members the severed parts of her husband Osiris thrown into the Nile by his jealous brother, Seth. With the help of Ibis-headed Toth, she retrieves all but his phallus, swallowed by a fish. This doesn’t prevent Osiris from fathering an only begotten son, Horus, his representative on earth. We might call Horus, the falcon: Consciousness Fathered by the Wounded One.

Osiris takes his place as Lord of the Underworld (Duat) where he presides over the fate of souls after death, depicted in hieroglyphs as birds that fly into the underworld. Osiris guides the soul, dis/membered by death, in a transformation through which the wound is healed and the soul restored in the body of Osiris—fulfilling what will be articulated in the Great Christian Mystery: “my father and I are one.”

Nerfertari as Ba, Tomb Painting, 3,200 BC

Nerfertari as Ba, Tomb Painting, 3,200 BC

The Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom clearly tell us that souls in the Duat are “regularly and continually” challenged to undergo transformation. The union of the ba (embodied soul) and the ka (vital spark), form a third, the akh (the effective one). The akh, as the pure light of consciousness, is represented in hieroglyph by a crested ibis, bird of the wise god Toth. The Pyramid Text stipulates that should the ferryman refuse to transport King Unas’ soul to the other side: He will leap and sit on the wing of Toth.

Papyri and tomb walls exhibit images of birds and feathers everywhere. For the world’s oldest high culture, birds embodied distinct intelligences essential to specific gods and goddesses. Amon, the “hidden source” or uncreated creator is a feathered crow. Amentet, the setting sun, who prepares souls for rebirth, appears with wings and holding a hawk’s feather. Shu, god of the atmosphere, wears ostrich feathers. Isis, wife of Osiris, mother of Horus, sports a vulture head dress and the rainbow wings of a kite. Horus is a falcon. Osiris wears white feathers on either side of his crown. Ra, the Sun and first Pharaoh, has a hawk’s head. Kephri, at sunrise, becomes the Bennu, or risen Phoenix. A single feather belonging to Ma’at on the scale in the Hall of Two Truths determines the fate of all souls. Souls lighter than her feather become Akh and are welcomed to paradise. Those less fortunate are devoured by the crocodile jaws of Ammit.

Goddess of Balance, Ma’at spreads her ostrich wings over gods and humans.

Goddess of Balance, Ma’at spreads her ostrich wings over gods and humans.

Sea-birds also link the world above to the one below. Their feathers are talismans. Olson’s kingfishers vanish into the shadows. Their feathers are evidence of a forgotten unity that calls to us unheard. Birds, visible by day, accompany Ra’s solar barc on its Night Sea Journey through the underworld, as did the golandrina, which I failed to recognize as my ba-bird. Birds, especially the swallows, become the vehicles for souls in the underworld, and for their transformation. The Bennu, the Egyptian phoenix, rises and sets with the sun.

The Osiris Mystery, as both myth and ritual, marks the early intuition of an objective intelligence in the unconscious. The drama of transformation in the Underworld describes the potential that takes place in our own psychological depths. Olson’s representation of the soul as kingfisher, a force precipitating the unchanging will to change, and its loss, constitutes more than his own gloss on the old myth, but a new one for our time. Perhaps the de-potentiation of mythology itself, the loss of any symbolic narrative that gives culture coherence and the way of enlarging individual consciousness.

Parzival’s healing question can only be asked by one who has been weighed in the balance of Ma’at and become an akh. Olson’s poem, “The Kingfishers,” is an 11th hour cry for help!

“The pool the kingfisher’s feather were wealth why

Did the export stop?”

When the symbolic links disappear, we are left with lassitude. Anything more is difficult to grasp, certainly the world as a coherent whole. Fernand speaks from the shadows about the devalued kingfisher feathers. He addresses those who sit mindlessly around the stagnant pool full of slime. In the end what he asks is rhetorical, not so much a probe as a hook.

Drawn by the potential for transformation, the changeless will to change, Parzival becomes an embodied soul and asks the healing question. But what happens when Parzival, the Fisher King and the Grail itself disappear from consciousness altogether?

.

8 -Rubedo, The Reddening

Olson loved to dig among stones. Indecipherable Mayan Glyphs spoke to him of buried intelligence in images of serpents and birds, heads dressed in woven feathers, the rise and fall of a high civilization incised on clay tablets. These elusive messages held valuable if undisclosed information: how do advanced systems decline into devalued plumage, slime in the pool.

I pose you your question:

Shall you uncover honey / where maggots are?

I hunt among the stones

In the coastal Mayan ruins of Dzibilchaltun, and rubble of “Dogtown”, the Gloucester settlement abandoned after 1812, Olson was drawn to the haunt of civilizations that carved the clues to their demise in stone. He knocks on the door of the unconscious.

Courage, Dogtown, Gloucester/Cape Anne

Courage, Dogtown, Gloucester/Cape Anne

Olson asks, Shall we find honey where maggots are? He might be speaking of the alchemical work which begins in the decomposing nigredo. He may be referring to the condition of mythological structures that once supported these high civilizations now sinking into the earth, and our own, on the way to becoming a Waste Land.

Olson begins Section 2 of “The King Fishers” with the self-mythologizing Mao, who forbids the centuries old custom of binding women’s feet, while proclaiming the risen sun, la lumiere,” as the symbol of a mythless society. In 1934 he will lead his followers on a long march toward l’aurore, and later, in 1949, as leader of the Peoples’ Republic of China, mount a cultural revolt outlined in his Little Red Book to entirely erase the past. After considering Mao’s position, the man who hunts among the stones weighs in.

He thought of the E on the stone, and of what Mao said

la lumiere”

mmbut the kingfisher

de l’aurore”

mmbut the kingfisher flew west

est devant nous!

mmhe got the color of his breast

mmfrom the heat of the setting sun!

In search of a myth for a mythless world, Olson’s avian avatar flies west, redness baked into its breast. He invites us to ride Ra’s Sunship into the underworld accompanied by swallows. In the Egyptian narrative the sun is totally eclipsed and for a moment faces the danger of total extinction. This happens every night. It appears to be what Olson wants us to consider.

Ra in the Sun Ship, Egyptian tomb painting, 1,200 BC

Ra in the Sun Ship, Egyptian tomb painting, 1,200 BC

There are twelve houses one must pass through on the Egyptian Night Sea Journey corresponding to hours between sunset and sunrise. Each hour presents its own dangers. A Coffin Papyrus shows three ba-birds in the 5th hour there to protect Ra against devouring chaos, the serpent Apophis.

Ra uniting with Osiris, Temple of Optet, 1,200 BC

Ra uniting with Osiris, Temple of Optet, 1,200 BC

Ra grows darker and weaker as the hours pass; even his guardians are afraid. There is no guarantee that chaos will not at some point swallow Ra’s light. At the darkest hour, when it appears all may be lost, Osiris, “the Hidden Soul”, meets Ra face to face. In that moment, the high-voltage transformation takes place. In the Mystery of the Two become One, both are renewed. In the Duat souls are continually transformed into enlightened akh.

Light at the core of darkness, The Red Book, C.G. Jung

Light at the core of darkness, The Red Book, C.G. Jung

On a cosmic level this takes place nightly when wounded Ra consciousness is united to the Osiris intelligence in the unconsciousness. The union gives birth to a third in Kephri, the newborn Sun. This is also the end result of the Work, the red which alchemists call the rubedo. The transformation which starts with the blackening nigredo, moves through the bright white albedo, to Kephri’s light. Both the Egyptian Night Sea journey and the Alchemical phases can be viewed as the movement from despair, through understanding, to enlightenment.

A Hymn to Osiris states: “Thou risest in the horizon, thou givest light through the darkness…”

Theatrum Chemicum, Gerhard Dorn, 1661

Theatrum Chemicum, Gerhard Dorn, 1661

Gerhard Dorn, the 16th Century alchemist prized by Charles Olson and Carl Jung, speaks of a “hidden third” arising from the two as “the medium enduring until now in all things…” Jung refers to this as a “synthesis of the conscious with the unconscious,” as a unio mystica. Ra’s transformational connection to Osiris can be compared to Parzival’s to the Fisher King; both describe this underlying unity in the alchemical marriage. Ironically, this was also observed by Chinese alchemists in antiquity and recorded in The Secret of the Golden Flower, which survived Mao’s “cultural revolution.” What the Egyptians called Akh, Western alchemists like Dorn the “philosophical stone,” the Chinese text refers to as the “Diamond Body”.

Mao wasn’t interested in hieroglyphs or alchemy. Symbolic thought of any kind became anathema. His demythologized Revolution reduced civilization to a simple surface. Hence Olson’s open question: What happens when only the feathers are left?

He answers it in “The King Fishers” by attempting to re-mythologize the wounded cultural psyche, to locate the place in which the archetypal transformation enshrined in the sacred traditions of all cultures can occur. Even so, Olson feared that it might be beyond reach at the beginning of a period which he was the first to call “Post-Modern.”

Olson asks: Where do we find what we have lost?

“The Kingfishers” is a fragmented psychological treasure map missing that piece where X marks the spot. We are given clues: the changeless will to change, the king fishers, and in the absence of the seabirds, their lore and feathers—representations to challenge us in the absence of a living mythology. Of course there is always the possibility that what Mao did by coercion in China, we are doing in a Post-Internet world by attrition. We may be losing the ability as a species to bring the latent intelligence to light.

.

9 – The Alchemical Nest

Chaos stalks our hi-tech lives more powerfully than ever; one inspired hacker-child could send our infrastructure into a tailspin. The same holds true of our personal infrastructure. The Underworld is no longer the place in which souls are weighed or balance restored by Ma’at’s feather. Our psychology is haunted by forces denied, degraded, or disguised as ideologies, religious and political, that set us at odds. Fundamental religious beliefs fused to nationalist politics are fueled by thanatos, an unconscious death-wish. The ecology deteriorates while gods past and present disappear beneath the waves.

Pacal Descending to Xibalba, Tomb at Palenque, Mexico

Pacal Descending to Xibalba, Tomb at Palenque, Mexico

In his study The Fisher King and The Handless Maiden Robert Johnson paraphrases Jung: “We no longer have Zeus but we have headaches instead. We no longer have Aphrodite and her noble feminine realm but we have gastric upsets. To dethrone anything from consciousness to unconsciousness is to diminish it in stature to a symptom.” Just so, the wounded Fisher King, split off from ourselves, becomes a hive of symptoms. T.S. Eliot’s Wasteland is inhabited by hollow men.

Will you leave it there? Pedrolino’s question is rhetorical. What will you tell them?

From his post on the wall, this black figure in his domed hat outlined by a white line on a black field gazes down from a moon face that glows like polished silver. He is the soul of old Ferrini, author of Know Fish. His words crawl through my mind.

“Tell whom?” I protest.

Pedrolino doesn’t answer, but I know. He is referring to those who will come to hear me read from Fishing On The Pole Star, directly followed by my talk, “Trolling with the Fisher King.”

It occurs to me that when only feathers are left, we must use them as lures.

Olson does just that; he uses feathers and stones the way a shaman employs a single bone to re/constitute the entire body. He builds the poem as king fishers do their nests with the remains of rotting fish bones. By gathering the “rejectamenta,” decaying bone splinters of myth, personal, and historical memory he builds to re/member.

…it does nest with the opening year but not on the waters.

It nests at the end of a tunnel bored by itself in a bank. There

Six or eight white or translucent eggs are laid, on fishbones

Not on bare clay, on bones thrown up in pellets by the birds

I’ll describe to my audience the scene I witnessed on a bank of the Sibun River. I could smell the rotting fish bone chips from my canoe. Warmed by the heat of that decaying mass kingfisher eggs hatch on the bones of their prey. Future generations will rise from this matrix of remains. From its heat, words are born, take flight, hover and dive. It suddenly strikes me that Olson’s poem about the process is itself a nest of decaying bone chips.

Pay attention, whispers Pedrolino. “You’re close.”

I stop and listen. An idea comes in an open inner window—an insight. Not simply a piece of information, but an epiphany. I must instruct my audience not simply to see what is being described here with the mind’s eye, but to bring all the senses to bear—to hear the birds chatter, feel the river flow beneath the craft, touch the oars, the gunnels, smell the decaying bone chips, let the sulphurous odor of the nests sting the nostrils. Instead of solving the mystery he presents in the opening of “The Kingfishers”, Olson gradually shifts the emphasis from product to process. We must be in it totally to realize what is going on here. The question of what happened to the kingfishers is never answered in the poem—but by the poem. What fledges from it dives like a sea-bird into the unconscious.

Contemplating Mind Before Thought, Secret of the Golden Flower, 1668

Contemplating Mind Before Thought, Secret of the Golden Flower, 1668

.

10 – Parsing (Parsivalizing) the Question

In his Holocaust memoir, Night, Elie Wiesel describes the secret teaching received by his young alter-ego, Elie, before the entire shtetle was transported to Auschwitz. Bare-foot Moshe the Beadle, who cleans the synagogue, instructs his young protégée, “At the end of your life God measures you by the depth of your question.”

In this teaching, authority isn’t captured by the answer. The deepest question answers itself by deepening. The mythos lies too deep for words but can be alluded to in a myth. Such is the wisdom imparted at the beginning of Wiesel’s narrative that portrays the naked depravity under the veneer of civilization capable of destroying ancient cultures and turning cities into rubble.

Olson asks, “The Kingfishers! / Who cares/ For their feathers/Now?”

Holden Caulfield, in Catcher in The Rye, wants to know, “Where do ducks in winter go?”

Chretien de Troyes’ Perceval inquires, “Who does the Grail serve?”

Von Eschenbach’s Parzival wants to know, “What ails thee?”

From Isis to Olson, we are challenged to re/member what has been left to languish in the dark. In every case, the healing power of the question is measured by the depth of the one who asks it. But what if the question itself is forgotten, lost, out of reach—or, more to the point, there is no

one to bring it full voice into the world?

Parzival, from the Feirefiz Project, Liz Neilson

Parzival, from the Feirefiz Project, Liz Neilson

,

11 – Spreading the Word

Olson’s vanished kingfisher constitutes a loss of myth, and with it our connection to the unconscious, its potential to transform fragmented souls, the ka and ba of us, into an akh, “the effective one” or pure light of consciousness. As a consequence, something has slipped from our grasp that once linked atoms to the stars and bound existence into a unified whole.

“The Kingfishers,” begins with a comment that might easily go unremarked: He woke, fully clothed, in his bed. He / remembered only one thing, the birds…

I might have disregarded it entirely had I not been for my encounter with the spirit of place, the essence of old Ferrini caught by an etching on the wall. No sooner had I named him Pedrolino, than he spoke to me, as he does three days later, after I wake from the same recurring dream. I’m in a room full of folding chairs. They are empty at first, then people file in to fill them. They’ve come to hear my talk. I smile at them. They smile back. Everyone is dressed in blue and green: my ba-birds. I wake in cold sweat.

There has to be something I can tell them about “Trolling with the Fisher King.”

Listen, counsels Pedrolino.

I just need a little more time to tie things together. These are my two thoughts and perhaps from them a third will follow. 1) Olson fishes the imagination for something born on a nest of decaying bones, that voice from the underworld speaking through him, the poet, telling us to hear in this moment what “was differently heard// as, in another time…” and 2) birds guide dead souls in the underworld, and shield Ra in the 5th hour of his Night Sea Journey from the devouring maw of Apophis, which would extinguish the light. Then it comes to me, out of the tension of the two, a third suggested in von Eschenbach’s Parzival 3) that the lapis exilies, or Holy Grail was delivered to us by “the neutral angels” while a war between opposing camps raged in heaven. This may be an expression of the unchanging potential inherent in our psychic structure, a constant that binds our atoms to the stars; our mission is to apprehend what we already contain, the numinous as the thing in itself.

The message I will convey to my audience of ba-birds, is this: each one of us is a wounded Fisher King trolling uncertain waters. We must keep our lines in, follow the sea-birds. The voice we listen for is equally uncertain. It comes through us, “heard differently//as in another time,” but is not our own. The fate of the world from which it rises depends on it.

“O city of mediocrity…”, Olson is Gone, But We Are Here, Peter Anastas, 12.24.14

“O city of mediocrity…”, Olson is Gone, But We Are Here, Peter Anastas, 12.24.14

.

12 – Epilogos

Charles Olson sought out Carl Jung when the latter spoke at Harvard in 1938, and engaged him in conversation about Herman Melville. The fever dream of wounded Ahab’s obsession with the whale pales in anticipation of the world driven to the brink of the abyss. Olson published “The Kingfishers” in 1949, long after public knowledge of the Holocaust and the bombing of Hiroshima had redefined civilization, and the year that Mao established the Peoples’ Republic of China. Jung was also putting together the connection between the transformations described by the Sun’s journey through the underworld, the Alchemical Work and his own theory of individuation as a transformative relationship between the conscious and the unconscious.

The Belgian alchemist Gerhard Dorn summed up the situation in his Theatrum Chemicum: “The sun is invisible in men, but visible in the world, yet both are of one and the same sun.” Olson and Jung were drawn to Dorn, a fellow Fisher King.

Plaque on Fort Street, Paul Pines, 8.2014

Plaque on Fort Street, Paul Pines, 8.2014

I feel Olson this afternoon as I walk through town to Fort Street to find the modest multiple dwelling house facing the bay. A plaque affixed to the peeling white wall is a tribute to the insistence of Henry Ferrini, as much as it to Charles Olson. My host at the Gloucester Writers Center, and Vincent’s nephew, Henry petitioned the city fathers for the installation until they relented. It remains the only physical evidence that locates Olson where he lived, looking out at the channel between the Inner and Gloucester Harbor.

Today, Gorton’s huge plant that hugs the shore along Roger’s Street facing the State Fish Pier processes frozen catch from foreign waters. The depleted local fishing grounds, and the plant that packages fish for export echo the missing kingfishers in the poem. I marvel that it was Olson who coined the term that defined such an age: Post Modern. And that he found in Gloucester material to create a mythic monument to what had been lost.

In Parzival the question is asked and answered; at the end, the Fisher King is healed and the land restored. In our time, we have yet to frame the question.

We fish to bring it to light. This is the theme of my book, Fishing On The Pole Star.

There’s a moment in my book, after weeks on the troll, just beyond Concepcion Island, when I hook a three hundred pound marlin, fight him for almost two hours, then bring him to the starboard side of our boat. Our mate holds him in place to “swim him.” The idea here is to quiet the creature and move him slowly until the water circulating through his gills restores color depleted after our struggle.

Color is important.

No shark in the ocean can best a marlin in full bloom. Dimmed, he is doomed.

Our big boy allows us to swim him until bands of green and blue blossom the length of his body. Then he bites down gently on the hand of the man who is holding him to signal he’s ready. The power in his great jaws could take the arm of his handler off at the shoulder with little effort—but the touch is delicate, almost reverential. Upon release, he rides up over the gunnel to meet our eyes with his large circular orb, full of an intelligence so balanced, so complete, I glimpse in it the Divine Child, and also The Grail. I think, Here is the constant which links the atom to the stars, and binds existence into a whole.

And then he is gone.

Sunrise by the Ocean, Vladimir Kush

Sunrise by the Ocean, Vladimir Kush

—Paul Pines

.

PAUL PINES grew up in Brooklyn around the corner from Ebbet’s Field and passed the early 60s on the Lower East Side of New York. He shipped out as a Merchant Seaman, spending August 65 to February 66 in Vietnam, after which he drove a cab until opening his Bowery jazz club, which became the setting for his novel, The Tin Angel (Morrow, 1983). Redemption (Editions du Rocher, 1997), a second novel, is set against the genocide of Guatemalan Mayans. His memoir, My Brother’s Madness, (Curbstone Press, 2007) explores the unfolding of intertwined lives and the nature of delusion. Pines has published twelve books of poetry: Onion, Hotel Madden Poems, Pines Songs, Breath, Adrift on Blinding Light, Taxidancing, Last Call at the Tin Palace, Reflections in a Smoking Mirror, Divine Madness, New Orleans Variations & Paris Ouroboros, Fishing On The Pole Star, and Message From The Memoirist. His thirteenth collection, Charlotte Songs, will soon be out from Marsh Hawk Press. The Adirondack Center for Writing awarded him for the best book of poetry in 2011, 2013 and 2014. Poems set by composer Daniel Asia have been performed internationally and appear on the Summit label. He had published essays in Notre Dame Review, Golden Handcuffs Review, Big Bridge and Numero Cinq, among others. Pines lives with his wife, Carol, in Glens Falls, NY, where he practices as a psychotherapist and hosts the Lake George Jazz Weekend

Douglas Crosbie, Lynn’s father, reading to her and her baby brother James.

Douglas Crosbie, Lynn’s father, reading to her and her baby brother James.