.

My father said I didn’t need a college education, even though my brothers had university degrees and he’d grudgingly allowed that I was just as smart as they were. He thought I should be a secretary, marry the boss, have kids and be a housewife like my mother and aunt, the grandmas I’d never met and generations of bored, angry women before them.

This was not an unusual way for a European immigrant to talk to his American-born daughter in 1967, a year before urban feminists organized a protest at the Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City that made Women’s Liberation a national force that would eventually change my attitude toward my appearance, housework, birth control and workplace inequality. In the meantime, as a consequence of my father’s meager plan for my future, I didn’t learn to type well, which limited my job opportunities in subsequent years.

I loved reading and writing and had always done well in school, encouraged by enthusiastic New York City teachers to continue my education. At thirteen I’d won a city-wide short story writing competition and was awarded a volume of Shakespeare’s complete works, illustrated by Rockwell Kent, which convinced me I was destined for great things. But first I needed to go to university.

The compromise I finally reached with my dad was that he’d cover my room and board if I agreed to live at home and find a job to pay for tuition, books and incidentals. The best deal in town in terms of cost was the City University of New York, so I applied to the nearest branch, Queens College, and began to look for work at once.

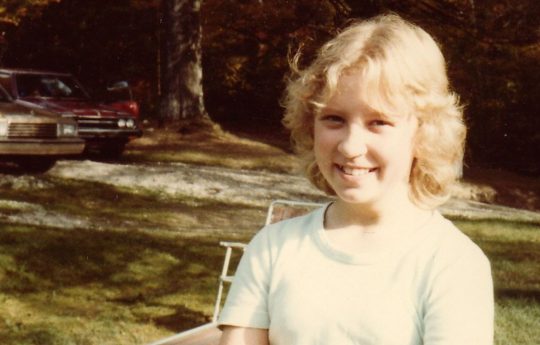

High school graduation

High school graduation

We lived in Far Rockaway, close to JFK Airport and edging the Queens-Nassau County border. It was so far off the beaten track that when you exited the subway at Mott Avenue, the last stop on the “A” train, you had to pay an additional fare—an indignity that continued until 1975. Rockaway Beach and its boardwalk on the Atlantic and a popular diving spot my brother Stan explored in wet suit and scuba gear for many years were the area’s main attractions, plus Rockaways’ Playland, in the middle of the peninsula, with its famous roller coaster. There were rickety wooden bungalows in the Rockaways that people used for summer getaways, and Patti Smith mentions in her memoir M Train that she recently bought such a house, damaged by Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

The trip from my home to Queens College in Jamaica took nearly two hours by bus each way. Along the route to the campus on an endless highway was a large shopping center, and this, I decided, was a good place to find work, even though I had no usable skills and my most notable attributes were a large vocabulary and what my father referred to as a “fresh mouth.” None of this mattered, I soon learned, when looking for minimum-wage, highly undesirable jobs. I was hired on the spot for anything I applied for on the strength of my high school diploma, my ability to add numbers, speak nicely and smile a lot.

The author’s father cycling on boardwalk, 1966

The author’s father cycling on boardwalk, 1966

.

.Practice Jobs

I signed on for a full-time job the summer before starting university in the Womens Clothing Department of a downscale store on one side of the highway. There was no apostrophe in “Womens,” I noticed, but was smart enough to keep that detail to myself. Dolly was my manager, a slim, petite woman in a body-hugging skirt and a blouse with a few buttons shockingly undone at the top. She was older than me, but not by much, a dark-skinned Hispanic who laughed easily and walked adroitly on high heels, something I admired because it was beyond me. She never explained exactly what I was supposed to do and often left the department for half-hour breaks, but by watching another girl on my shift I determined that my main task was to empty the fitting room. This involved tidying clothes on hangers and putting them back on racks on the floor, over and over again.

The author’s brother in wetsuit and scuba gear

The author’s brother in wetsuit and scuba gear

Occasionally a customer would ask for assistance and I’d help her search for a garment in a size we invariably didn’t have or bring her something else to try on while she was half undressed in the fitting room. I was mesmerized by much of what I saw there—loose, large breasts with dark, intimidating nipples; pouchy bellies; thick waists; enormously wide hips; doughy, dimpled thighs. I was still only a tall, leggy, wee-breasted teenager with limited knowledge of other female bodies, aside from my mother’s. I knew more about young men because a couple of boyfriends had instructed me in the unpaid work of giving them hand jobs and the occasional blowjob so they could get their rocks off without the stress of full performance.

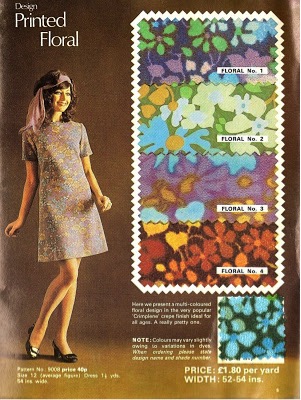

When Dolly was actually in the department, she spent her time trying on clothes in the fitting room. My role was to say how terrific she looked before rehanging the items and returning them to the floor racks. She did, in fact, look great in anything she put on, though I knew, because I had sewn things myself from Vogue patterns, that everything we sold in the Womens Clothing Department was poorly cut, badly stitched, unattractively designed and made of cheap fabric that crackled and sparked when you pulled it on or yanked it off. That didn’t bother Dolly at all, and I envied her confident self-absorption and the fact that as a manager she didn’t have to stand around doing achingly boring work.

My feet were killing me. Aside from two short breaks and a half hour for lunch, I never got to sit down on an eight-hour shift. Sure I was young but I had a design flaw—easily tiring legs—and knew I wouldn’t last past the end of summer. But when I finally told Dolly the job wasn’t working out, she came to my rescue. “Mr. Thomas can use a smart girl like you,” she said. “No one ever shops in his department, so you can sit on a chair and read.”

And so that fall I transferred to the Linen Department, where Mr. Thomas was my boss. He was a very tall, very skinny black man in a silky white shirt and floppy trousers that slapped his legs when he moved, and he spoke in a lilting accent I couldn’t identify. Something Caribbean. He walked me around the floor, reciting measurements for sheets and blankets that went straight out of my head, and gave me a crash course in quilts, pillows, mattress covers and pads. For some reason the Linen Department sold roller window shades, and when he showed me the cutting machine I shot to attention.

First the wooden slat at the bottom of the shade was removed, measured and cut with a blade pulled down on it, and it broke with a delicious snap. Then the rolled-up vinyl shade, locked in a narrow trough, had to be carefully measured against a ruler guide. Any excess was sliced off exactly with a jaggedy-toothed electric blade that made a satisfying roar. Precision work, indeed. Here was something I was actually proud of, a bona fide skill that would open a world of future hardware store positions for me.

There were very few customers, as Dolly had promised, and when I wasn’t cutting shades I sat on a chair by the door of the linen stock room and scribbled notes for my Freshman English essays. Dolly would often appear out of nowhere to discuss something or other with Mr. Thomas, and I would greet her happily. Sometimes they would vanish into the bowels of the stock room, closing the door behind them, and I’d be told to summon Mr. Thomas only in an emergency and left to handle the floor myself. I was honored by his faith in me, pleased to have the chance to play department manager, and didn’t grasp that I was really playing lookout.

The stock room was a dark, cold, two-story labyrinth with packages of linen on open latticed shelves and a clanky, metal staircase at one unseen end leading to the second story. I almost never went inside, preferring to tell a customer we were out of stock than to search for something on the shelves. A more-or-less innocent seventeen-year-old, I was never quite sure what was happening with Dolly and Mr. Thomas in the bowels of that scary place, though I could hear them climbing steps to the upper level. Maybe they were just friends, just chatting, killing time. Well okay, maybe more. Possibly they’d made a bed of quilts on the narrow metal walkway and were actually “doing it.”

One day Mr. Thomas failed to show up and I was told he’d “moved on.” Dolly, who got along extraordinarily well with the pudgy store manager, continued running the Womens Clothing Department, but I was summarily “let go.”

My hurt, nausea and outrage at the unfairness of my dismissal throbbed in my throat, but I got over it soon enough and found work in a rival department store on the other side of the highway.

Cooking in the backyard, Far Rockaway

Cooking in the backyard, Far Rockaway

.

.The Refunds Department

This was truly an awful job. I was told I would “interact with the public,” which meant I got to stand behind a chipped and ink-stained Formica counter in the Refunds Department, a windowless room with walls painted the sickly yellow-beige of the paper my mother’s butcher used for wrapping meat. In front of me, for as far as I could see, was a bunched-up line of pissed-off customers holding various packages and items of clothing with limply hanging sleeves and pant legs. It was just after Christmas and the line was inexhaustible. I was slow to check people’s receipts and the condition of their bundles, slow to open the ancient register and return cash, and by the time anyone finally got to the counter their face was a bursting sausage of fury.

Once again my feet were killing me, and I slouched behind the counter with one hip cocked. Why wasn’t there so much as a bar stool I could use? Given my height, no one would even know I was sitting down!

At regular intervals my boss would quietly emerge from the back room to pat between my shoulder blades and admonish me to stand up straight and smile. She never helped advance the line by dealing with customers herself.

I hated her. She was middle-aged, curveless, a head shorter than I was and didn’t make small talk. She always wore wool suits in muted colors with skirts inches below her knees, and although every outfit clearly cost more than I earned in a month, I found them all ugly. Her hair was dyed white-blond, her eyes and mouth tellingly small, her skin only a shade lighter than the overbearing walls. I missed Dolly and Mr. Thomas with a pain in my chest like love.

After a few shifts I was called into the back room and led to a chair by a desk, and my boss instructed another girl to take my place at the counter. The girl hissed a nasty word at me as she elbowed past.

My reward for doing good work—for abiding the verbal abuse of customers, taps on my back and endless achy hours on my feet—was the joy of sitting down awhile in an airless alcove to tally receipts and expenditures under the glaring eye of a desk lamp. Alternating between the front counter and back room, I thought I could slog through until something better turned up.

My shame and downfall came at the hands of an elderly lady. Her fingers were arthritically clawed, her rubber-soled shoes worn, and her twisty varicose veins bulged under her stockings. I felt bad for all the time she’d spent in the line-up. She approached me grinning, a rare thing, and I found myself grinning back, my heart suddenly leaping. “I hope you’re having a nice day,” the old woman said, and I wanted to vault the counter to hug her.

What she spread before me was a stiff yellow girdle that was certainly many years old. She had no receipt, she sighed, because it was a present from her much-loved husband who’d died over Christmas—which Christmas, she didn’t say—and now she couldn’t wear it because it made her think of him, which gave her palpitations. She asked me for two dollars.

I only paused a sec before clanging open the register and handing her two wrinkled one-dollar bills. Quickly, guiltily, I swept the girdle into the Returns bin under the counter, and when I looked up the woman was gone.

My boss laid a hand lightly between my shoulder blades and leaned in close. “You’re fired,” she whispered.

Cycling on the boardwalk

Cycling on the boardwalk

.

.The Best Job Ever

Back across the highway, in a self-serve discount shoe store, I found the best ever part-time position. This was not a practice job, like the others, but the real thing, a perfect job, and one that lasted the rest of my university days.

Women’s and children’s shoes were arranged by sizes on open racks here, and for reasons unknown, customers would often separate pairs of shoes, leaving one on or near the proper rack and dropping its match elsewhere. My main task was to locate these “orphans,” as they were called, and return them to their right spots.

I was actually paid for this.

Of course there were benches everywhere so people could try on shoes, and I could sit down as often as I liked, pretending to straighten or dust the display racks.

There was a stock room with a metal door opened to the outside for truck deliveries, which allowed fresh air to waft into the store, as well as the odor of pot smoked by the stock boys. Bob, the store manager, was a thirty-something good-looking guy in a nicely cut suit and tie, someone I felt sorry for because he was stuck in a nothing-job—unlike the stock boys, who assured me they’d be gone soon—and so unhip he couldn’t identify the smell of marijuana. The regional manager sometimes sniffed the air when he came by now and then, but Bob always told him he was smelling incense or exhaust fumes from the trucks.

Now I wonder if Bob knew all along what he was inhaling and simply enjoyed it.

I hardly interacted with The Shoe Shelf customers or their kids, other than to point them toward appropriate racks, and left Bob to deal with complaints. Mostly I wandered the aisles in a dream-state on my dream job, slightly stoned from second-hand smoke, thinking about a paper due in my Shakespeare course. I planned to write an essay about the role of horses in Richard II, a fairly ridiculous topic, but I figured I could dash it off. Working several weekdays after classes and long shifts on Saturdays, I didn’t have time to think weighty thoughts.

On Far Rockaway beach, 1968

On Far Rockaway beach, 1968

The stock boys kept to themselves, I was the only clerk on the floor, and Bob stood up front at a desk, ringing up sales. When business was slow he’d pace back and forth or gaze out a floor-to-ceiling window at passing cars. I think he was lonely and needed a friend.

Sometimes he’d call me up front for no reason other than to talk about what he was reading or ask about my studies. He was always polite, never prying, and had a gentle, appealing manner. He also had a girlfriend and wanted us to double-date. This never happened. He said he was a cracker-jack cook and wanted me to join him and his friend at his house for dinner. That didn’t happen either. He wasn’t at all sleazy and I wasn’t afraid of him—in fact, I found him attractive—but I didn’t have time for socializing with someone I believed peripheral to my forthcoming, real and amazing life.

I knew I would graduate in a couple of years with a BA in English and find a job in Manhattan better than the one I had at The Shoe Shelf. Bob, I imagined, would always be stuck in Queens, and I wouldn’t find him interesting after I became a cosmopolitan feminist. I wanted an adventurous life filled with daring, gob-smacking experiences, and really there was no room for a shoe store manager friend in such a life.

Maybe I was too harsh. But I forgive my teenage self, cloudy-eyed with optimism, anxious for independence, determined to be the writer I knew I was meant to be. What I secretly hoped for was suitably undemanding work—not unlike my job at The Shoe Shelf—that left me energy enough to write novels late into the night, but naturally one that paid a good deal more.

With such dreams I staggered forward and formed a life. An interesting one, as it turned out, true in many ways to what I’d envisioned as a girl in Far Rockaway; different in ways that were then unimaginable.

Which is how a life goes.

—Cynthia Holz

.

Cynthia Holz is the author of five novels and a collection of stories. Her short fiction has appeared in numerous literary journals and anthologies, and her essays and book reviews have been widely published. Born and raised in New York City, she lives in Toronto. Her website is www.cynthiaholz.com.

.

.