In the dark days after the humiliating defeat of our villanelle, Paris and I have done some serious soul-searching. The defeat weighs heavy on her (as it does on the author.) She remains convinced that the Numero Cinq readership failed to identify the alternating motifs of pathos and love within the poem’s intricate structure. But alas, as Paris tells me frequently, “Get over yourself.” (Have truer words ever been spoken?) We will be back, she vows.

So sex then. An odd thing happened to me this semester: almost all of my stories became highly sexualized. I can’t blame my advisor for this, short of saying that he pressed me to build strong desire/resistance patterns in story structure. He admonished me to make something happen in my stories, but didn’t say how. As I reflected back on the stories I wrote this semester, I was surprised to see how I dealt with his guidance: I put a lot of sex in my stories. This lead me to ponder, why? I think the answer lies in a deeper, more complex relationship between the mind and the body, a relationship steeped in my culture and history as much as anything personal.

The Canadian poet, Steven Heighton, says that “violence is the sexuality of America.” In his essay, “Body Found in Reservoir,” he explores how portrayals of violence in North American culture reflect a punishment of the body for its sexuality. Another Canadian, songwriter Bruce Cockburn, put it this way in his song “Last Night of the World,”: “I learned as a child not to trust in my body//I’ve carried that burden through my life//But there’s a day when we all have to be pried loose.” I didn’t consciously seek to ‘pry loose’ this mind-body contradiction in my stories this semester. It arrived because I wanted to add a component of strong desire to my writing, but at what point does a torrid sex scene become, as my wife recently commented on one of my stories, gratuitous? Heighton says this:

Violence is the sexuality of white North America because violence is all we have left. The passions demand a physical outlet but in our bones we feel it’s somehow wrong to love the body. So sex—no matter how aggressively marketed or universally portrayed, no matter how frankly and coolly discussed on talk shows or in the narcotic literature of self-help—remains fraught with an obscure gloom and guilt.”

Hollywood certainly offers up raw sexuality at every turn. To return to my muse: Paris Hilton embodies this contradiction. Her sexuality certainly calls attention to her body, but the mind seems a tad empty. (Sorry P.) Our culture in general offers the body willingly, with its ubiquitous promises of a perfect, unobtainable model (botox, liposuction, laser hair removal, Hair Club for Men, etc.) Yet all these ‘cures’ seem to take us further away from the real body and into some hyped-up fantasy of perfection, which constantly implies that such perfection lies tantalizing close but always a hair-breadth out of reach. Steven Heighton puts it more eloquently:

For the first few hundred years, it (the hiding of the body) worked. Nowadays, if North Americans are still fundamentally puritanical, they show as much skin as anyone else—though in this seeming casualness there’s a strain of the frantic exhibitionism I mentioned before in regard to porn. No group of people at peace with their bodies could muster such sad, huddled masses of anorexics and bulimics and the world’s highest per capita rate of abuse of steroids, sleeping pills, sedatives, and laxatives.

So back to my sexual drift this semester: Did my use of sexuality in creating characters or situations reflect a healing of the mind-body? Can I continue to write about sex without turning it into soft-porn? The following sexual motifs appeared in my last four stories: men masturbating each other in a foxhole, a threesome, oral sex in a parking lot, and S&M scenes between a husband and wife. None of these stories was explicitly about sex, but these recurring situations gave me some pause. Clearly a good sex scene ratchets ups the tension in a story, but writing about sex is certainly not daring anymore. So what am I trying to accomplish with this? A part of an answer might lie in Nancy Willard’s essay, “What We Write When We Write About Love.” (Found in The Best Writing on Writing anthology edited by Jack Heffron.) Willard describes a childhood scene where she is supposed to be watching a group of fraternity brothers serenading her sister as part of a courting ritual. Instead of watching, she turns her binoculars onto a couple in the back seat of a car, doing what couples do in the backseat of cars.

Writing a love story is a little like finding yourself with a pair of binoculars in your hand, caught between passion and scruples, ceremony and sex. If you err too far in either direction, you can end up on the side of pornography or romance. The difference between a love story and a romance is one of intent. When you write a romance, you carefully follow where many have trod, so that your readers can recognize the genre through its conventions. But in a love story, you try to show love as if your characters had just invented it. Follow your characters, and they will give you the story, but you can’t tell ahead of time where they’ll lead you.

What I draw from this is that sexuality becomes a matter of intent, not content. It becomes a matter of healing, not manipulation. It arcs toward love, toward the fusion of the mind-body gap. It should celebrate, not denigrate. Heighton says, “wherever the flesh is hated, or endangered, love is threatened as well.”

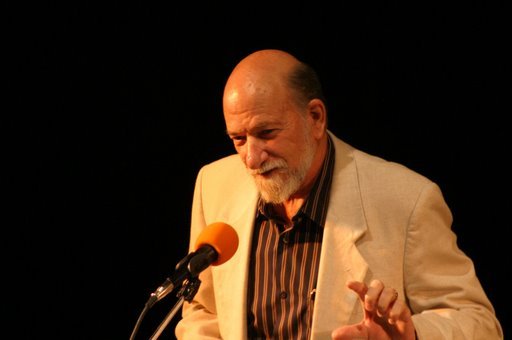

—Richard Farrell