Keilson the pioneer, surviving through pluck, fortitude, nerve, and extreme good fortune, is also Keilson the orphan, the homeless person, lost and abandoned. His very language in the diary entry confirms that sense of a split self. —Dorian Stuber

1944 Diary

Hans Keilson

Translated by Damion Searls

MacMillian, 2017

256 pages; $25.00

.

In 1944, the writer and psychotherapist Hans Keilson was in hiding from the Nazis in Delft, Holland. Unlike many Jews in Holland who had gone to ground—including the teenaged Anne Frank only forty miles away in Amsterdam—Keilson was able to live openly, under the name of Johannes Gerrit van der Linden. He was fortunate to have fallen in with a resistance group that specialized in forging documents. One of its members, Leo Rietsma, agreed to house Keilson, and for almost a year Keilson lived with Rietsma and his wife Suus, ostensibly as tutor to their children.

For most of that time, from March through December 1944 Keilson kept a diary. After the war he forgot all about it. Many years later, towards the end of his long life—Keilson died in 2011 at the age of 101—it resurfaced and appears now in an excellent English translation by Damion Searls under the title 1944 Diary.

Keilson lived an extraordinary life. Born in 1909 in a small town in eastern Germany near the Polish border, Keilson moved to Berlin in the late 1920s to study medicine but was unable to complete his degree once the Nazis came to power. Instead, he trained as a gymnastics and swimming instructor and worked on his first novel, Life Goes On, published in 1933 but banned the following year, like all books by Jewish writers. Most importantly, he met a divorcee named Gertrud Manz, whom he later described as “an adult woman I could talk to as an adult man and who treated me as such.” It was Manz who persuaded Keilson to leave Germany for Holland in 1936.

In some ways, Keilson flourished in Holland, quickly mastering Dutch and gaining a residency card. He continued to write, publishing under various pseudonyms, and worked a series of jobs. But even though more successfully integrated than most émigrés, Keilson did not have it easy. He had to live apart from Manz—the couple had not been allowed to marry in Germany because of laws against intermarriage and they couldn’t in Holland either because they weren’t Dutch—even when their daughter was born in 1941.

From May 1940, when the Nazis conquered Holland, Keilson went into hiding. But his parents—he had managed to get them out of Germany in 1938—felt themselves too old for such subterfuge. They were deported to the transit camp at Westerbork and later murdered at Auschwitz. When he was writing the diary Keilson did not yet know their fate, but he suspected it; he regularly refers to the heartbreak of losing them (”Intense longing… for my parents. I talk to them sometimes. Oh, much too late!”; “If only I knew whether they were still alive”). This intuition of having himself been orphaned, together with his medical training, enabled his resistance work: he counseled children and teenagers in circumstances similar to his own, helping them ”get through the problems that erupted due to their long periods in hiding.”

He pursued similar therapeutic work after the war, as a psychiatrist in an organization dedicated to helping child survivors of the Holocaust. In 1979, he finally earned the doctorate the Nazis had denied him years earlier with a monograph on traumatized children that remains influential today. Keilson didn’t stop writing altogether—he published two more novels and a memoir—but medicine replaced literature as his life’s work.

In 1944, however, this outcome was far from certain. Over and over again in the diary Keilson wonders what will become of him. Not whether he will survive the war—although that anxiety thrums in the background—but what he will do with himself once it’s over. At one point, he unleashes a flurry of questions: “Which nationality? Be a doctor? Go back to school? Exams? Surely not that. Will they give us citizenship in Palestine? And then what? Plant orange trees? A chicken farm? Not me.” He zigzags between thinking of himself as a writer and as a doctor, worries how he will support his family, and dreams of security, precisely the quality he lacks in his current life, where everything is at once static and transitory.

For these reasons, 1944 Diary is as much an investigation of its author’s psychology as a document of its period. Keilson has surprisingly little to say about his daily activities, and even less about the war as a whole. (Even the most dramatic section—detailing a Nazi razzia or roundup in the streets around his hiding place—while he narrates in real time in interrupted by a bizarre and unsettling dream sequence.) In part, this reticence stems from the need to keep his resistance work secret should the diary ever fall into enemy hands. But mostly it’s a function of his conviction that what matters most in life is the inward struggle to represent experience. In an entry from September 23rd, after referencing the Battle of Arnheim, Keilson comments: “These events, however much they grip me, are no longer my real life.” What matters is “the other, main life—the human being, the poem, people together.”

Above all, Keilson values the idea of humanity, of being able to see another person “in their full humanity” rather than “in terms of a specific function.” But what did that mean for him? From what position should he strive to encounter that humanity? Keilson feels split: he is at once an artist and a family man, a poet and an “upstanding citizen and doctor.” The citizen, he sometimes laments, will be the death of the artist. Then he recalls his father’s last words to him—“Don’t forget: You are a doctor!”—and resolves to keep pursuing medicine. But he fears that won’t fulfill him. For months, he swings between the two positions, “always undecided, now being one and seeking the other, now being the second and seeking the first.”

Compounding this uncertainty is his love life. Shortly before beginning the diary, Keilson met a young woman named Hanna Sanders, who was in hiding at the home of two other members of the resistance cell, a ten-minute walk from his lodgings with the Rietsmas. Keilson and Hanna enter into an intense affair that lasts until Keilson returns to Gertrud and left his hiding place in Delft for one closer to her. Not coincidentally, the diary breaks off with this decision, as if to confirm that its function was to help Keilson work through the affair. In one of the first entries—unusually it is given a title, “No fear”—Keilson writes:

No more whitewashing. I’m saying what I say to myself in secret. The blank sheet of paper’s power to inhibit the writing and thinking process has been overcome. I will write down my thoughts and experiences. My conscience is not turned off, but it is no longer afraid of expressing itself.

Keilson doesn’t offer excuses for the affair (his separation from Gertrud, the uncertainty of life during war); he knows what he is doing is wrong. Yet he is inescapably drawn to Hanna. The relationship is as intense as it is truncated: Hanna’s movements are more restricted than his, the pressures they face are immense, and she knows about Keilson’s family life. In some dim way, Gertrud seems to have known about the affair, too: on one of the few occasions they are able to see each other, Gertrud begs Keilson, “’Please, no problems, not now.’”

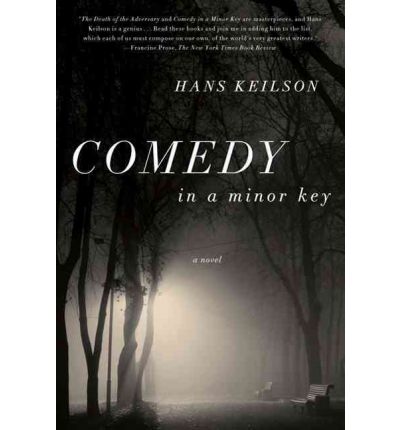

But Keilson makes problems, vacillating between Gertrud’s “deep maturity, understanding, empathy” and Hanna’s “loving affection and devotion,” as well as her forcefulness (this is as much physical as emotional: he “can’t stop thinking about the strong, uninterrupted stream I heard when she was sitting on the toilet “). The conflict torments him but it’s also productive. Poems pour out of him. He writes a novella in just a few weeks (it would be published after the war as Comedy in a Minor Key). At his most self-serving, Keilson justifies his infidelity as necessary for his art—suggesting that his productivity “depend[s] on living out a perpetual split”—but in general, as befits a therapist, he is clear-eyed and unsparing in his self-reflection. He never shies from presenting the darker aspects of his personality, noting more than once his “own sadistic tendencies,” which he calls a “deep bitter wound, almost like pleasure, at making another person suffer.”

Because Keilson is so open about his failings, we almost always sympathize with him. Keilson rarely compares Gertrud and Hanna, and never plays them off each other. Our interest in these women is a function of his own rather than something we arrive at by reading against him. Each is smart and talented; we understand why Keilson loves them both. Gertrud was a graphologist—in later years Keilson frequently told the story of the first time she saw Hitler’s handwriting: “’This man is going to engulf the world in flames’”—and Hanna was a translator, bringing Katherine Mansfield, among other writers, into Dutch.

The evenhanded self-scrutiny Keilson brings to his self-portrait is even more fully evident in his interactions with others. He counsels Leo and Suus’s nine-year-old daughter Hannie when she breaks into fits of terror at the idea of God (Keilson finds her response entirely reasonable). He intervenes in a tense situation between Suus and the other Jewish member of the household, a woman named Corrie Groenteman who worked as their maid. Corrie takes to her bed in tears at Suus’s disparagement and class resentment; Keilson reminds Suus that the “woman crying upstairs” had “her children in Poland, her home life torn apart, he family destroyed.” He is calm, judges as little as possible, diffuses hostility as best he can, concluding “My attitude was: They just have to be taught the understanding they lack.”

His work as a therapist surely helped him imagine points of view different from his own. This tendency comes out most strongly in an extraordinary entry describing Keilson’s encounter with J. C. A. Fetter, a pastor and psychoanalyst whose parish helped Jews. Keilson visits Fetter at his church in The Hague to ask him to pass some money on to Gertrud. He catches Fetter at the end of his rope; before long Fetter lashes out at Keilson: “Always these Jews… they rejected Christ, they excommunicated Spinoza—over and over again, they’ve provoked extraordinary responses from other peoples…It’s too much, it’s too much! Jews all the time, we can’t take it any more.”

Fetter’s outburst is classic anti-Semitism. But while we might be horrified, Keilson is not. He doesn’t accept Fetter’s rant, but he doesn’t reflexively reject it, either. Rather than screaming at him or turning away, he reaches out. First, Keilson points out, referring to Fetter’s own psychoanalytic experience, that people don’t ask for help unless they are desperate. He reminds Fetter that he, Fetter, had once supported the Nazis but had broken with them on “their solution to the Jewish question.” Rather than accusing him, he soothes him: “As a result of my open admissions… Fetter slowly came back to his senses.” It’s a remarkable piece of large-spiritedness and humanity in a situation where these responses were in short supply even among those who were mostly doing the right thing

Of course, Keilson isn’t always enlightened. He admits frankly to “deep satisfaction” at the destruction the Allies are meting on German civilians: “I’m filled with overpowering rage a lot of the time: Wipe ‘em out!” He dreams of revenge and even fantasizes about returning to Germany after the war as a kind of psychological spy, a person “to whom [the Germans] were mercilessly, unguardedly revealing their deepest secrets. That would be the greatest pleasure imaginable.”

More complicated still are his ambivalent feelings about his hosts, people he lives in such proximity to and to whom he is indebted—they have risked their lives for him—yet for whom he exists in the role as a subordinate, even underling. When in the midst of the Hongerwinter, the Hunger Winter, the famine of 1944-45, Leo miraculously comes home one day with a goose, the mood in the house improves dramatically, yet Keilson confesses “I felt terrible, violent envy over how it was divided up.” Later, on his 35th birthday, he broods over Leo and Suus’s indifference: “an utter lack of warmth and spontaneous kindness.”

Even though Keilson was free to move around the country—though he always risked having his papers found out as false or, more likely, being press-ganged as an able-bodied young man to serve the German war effort—he was still trapped. One day he runs into the author Marianne Phillips on the street—she too was living under a false identity—and the mutually admiring writers make plans to see each other. But when Phillips suggests visiting him at home, Keilson falls silent:

“I have to ask my people if that’s okay,” I said, a bit sheepishly.

“Me too,” she said,

Something snaps between us. The happy anticipation is gone.

My people. As if Keilson and Phillips are pets. Keilson has already reflected on why he reacts with shame when his poems are praised: “I realized that I have been living like an animal, a dumb beast, for a long time now, for years, almost.”

The diary is filled with similar expressions of anxiety and despair. Hearing a reference to “mass murders in Polish concentration camps” on a radio report from England, Keilson, atypically bitter, imagines a grim future:

We should take Jewish children when they’re still young and build up their immunity with small doses of gas, the Jewish state should, for the next pogrom! But who knows, the goyim will probably just use electricity then.

In what might be the darkest moment in the book, he is suddenly overcome by a vision of “a book full of gas, killing everyone who reads it.”

§

Damion Searls has done a great service in bringing this fascinating and gripping book to English-language readers. In addition to his vivid and powerful translation, Searls provides clear and helpful notes, along with a thoughtful introduction and afterword. My only criticism is that Searls misrepresents Keilson by downplaying his anger, fear, and shame. These emotions are almost as prevalent as his broadmindedness and enlightenment, but they don’t fit with Searls’s conclusions. For Searls, Keilson’s diary embodies the triumph of the individual over history, offering “a testament to finding one’s way amid horrors and conflicts of all kinds. Human struggles can outweigh even the Holocaust, world war, the Dutch Hunger Winter.”

But Keilson is anything but triumphant. Indeed, his experience allows us to think about the limits of even relatively lucky individual victims of Nazi persecution. In an entry from March 1944, Keilson remembers reading Kafka’s story “The Great Wall of China” and being moved to tears by the line “We sit dreaming at the window and wait for that message.” Despite his good fortune, despite his active resistance to fascism, Keilson is aware that events have made him an onlooker on his own life, a man who dreams at a window, waiting for a message. And when the message comes it might be too late, might not even be for him.

In the diary’s last entry, Keilson admits that “for six months now I’ve known that the war won’t simply end for us, with me coming back unscathed to an unscathed family in an unscathed home.” Yes, humans must struggle as best they can, as Searls puts it, but that struggle might not outweigh historical trauma. In one of his first entries, Keilson had already offered an extended meditation on what his diary—and by extension, he himself—can and cannot do:

The times when I write in this diary are my true moments of contemplation. It is a wellspring, my only chance to escape the lies. Yet still so far from the truth of my nature. All the unlived possibilities too, which haven’t been able to form my nature. Is longing enough? For me, it’s just a sign that I’m not yet totally a lost cause. I’m often in such uncharted territory, and then feel like a pioneer, far from my homeland. With courage, strength, endurance, venturesomeness, otherwise he wouldn’t be a pioneer. And then at night, by the campfire, a feeling of abandonment, homesickness, alienation steals over him. He gets used to it slowly, or never. Someday his children will be locals. I’ve had more than enough of this feeling already.

I once heard Jeremy Adler, the son of the writer and scholar H. G. Adler, who survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Buchenwald, say that unlike most of the writers we associate with the Holocaust, his father was a grown man when he was deported at age thirty-one. (Elie Wiesel, by contrast, was only fourteen, and Primo Levi twenty-four.) He had lived longer, stored up more experience, and been able to complete an education in a way many survivors, mere teenagers or young adults when their lives were uprooted and their worlds destroyed, had not.

Hans Keilson, thirty-four years old when he began his diary, was in a similar position. His life experience led him to see complexity everywhere. Keilson the pioneer, surviving through pluck, fortitude, nerve, and extreme good fortune, is also Keilson the orphan, the homeless person, lost and abandoned. His very language in the diary entry confirms that sense of a split self—as he moves deeper into his metaphor, Keilson’s pronouns shift from first to third person. But Keilson’s “I” was always also a “he”—he was always self-divided, not just from personal predilection or constitutional uncertainty, not just from intellectual commitment to Freud’s understanding of the unconscious, but more powerfully from his historical position as one who seems on the face of it not to have been a victim but was all the more wounded because his fate was so much better than so many others, even the rest of his immediate family.

“To see the other person in their whole humanity”—this ability, amply on display in this remarkable document, was Keilson’s great gift, not least when the other person was himself. Thankfully, 1944 Diary is not a book of gas, killing everyone who reads it. But neither is it a book of life, affirming individual resistance to terror and oppression. The odour of gas always threatens to waft from the page.

—Dorian Stuber

N5

Dorian Stuber teaches at Hendrix College. He has written for Open Letters Monthly, The Scofield, and Words without Borders. He blogs about books at www.eigermonchjungfrau.wordpress.com.

.

.