x

My first real job was in a hematology clinic in the late seventies. The office, located on Eight Mile Road in Detroit, was a small beehive of rooms where three clinicians saw patients, with five women acting as support staff. There I fell under the spell of one doctor who was everything admirable: a scientist, a professor, a musician, and also a little goofy. I was seventeen; we were perfect for each other.

My job wasn’t demanding: I called patients in from the waiting room, watched as the tech drew their blood, weighed them, and then led them to an examining room where I gave them a dressing gown and asked them to undress. The difficult part was seeing critically ill people day after day. But by the time I realized, my stint had ended and I returned to the summer vacation of the rest of my life.

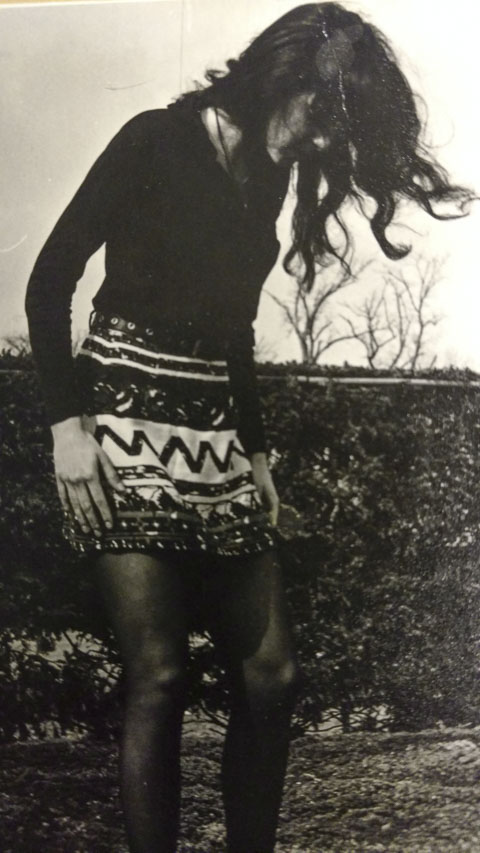

I’d just graduated from high school, which sounds very flags flying and trumpets blaring, when in fact I’d limped through my senior year until I finally stopped going months before graduation. My psyche had snapped. I couldn’t tolerate the people at school, the hubbub, the drama, the flat wooden desks, the washed-out teachers, the cacophony of the lunchroom, and the emptiness I felt there. Instead I stayed home in my room with its red carpet, wrought iron table, black and white bedspread, and woven headboard I’d spray painted black. There, in my twin bed, I read or wept until my mother demanded I do a household chore. The school must have mailed diploma.

Then in July, Henny, the office manager, asked me to return to the office as a full-time worker. My parents, who didn’t know what to do with me, probably saw the job as a godsend; a safe place where adults would watch over me instead of having me hospitalized.

Without the internal starch to resist, I zipped on a white uniform and showed up for work the following Monday. From then on, I slid on my virginal garb and performed the role of someone who functioned in the world during the week. One perk of showing up was seeing my hero in action. He was spectacular. He listened to others, treated them with kindness, ministered to their illness with a light touch, and sent them off hopeful.

I wasn’t alone in admiring Dr. A. The four other women who worked there also thought he walked on water. The office manager, Henny, led the pack. She was a Chihuahua-sized person who acted like a German shepherd. She scheduled appointments and collected payments from patients, scaring them into paying their bill with her blood red nails and dark scowl. The front office where she stood had a sliding window that opened onto the waiting room. Most of the time she kept the glass shut. She knew how to act professionally, yet without warning she could say the cruelest thing. Afterwards, in an Oscar-winning act, she’d disavow responsibility for her words. Scary stuff. I tried to stay out of her way.

Barb, the typist, also worked in the front office. She was a wiz at transforming dictation into typed pages, as if she were part machine. Though maybe seven years older than me at most, she seemed born of another generation. At lunch she did needlepoint and talked of her mother constantly, with a country twang that belied the fact she’d grown up twenty miles west of Detroit. She also loved hair spray; by Friday amber beads pearled the strands of her red hair. Sometimes she’d show me a passage from one of Dr. A’s reports. His writing was lyrical, cogent, and humane. Barb never mentioned the reports of the other two doctors whose work she also transcribed.

The insurance gal worked in the back section of the lab. She was a tiny person born in Wyandotte, a blue-collar town downriver from Detroit. She was sort of pretty, but there was an off-putting dark cast to her personality. If she didn’t agree with something I’d said, she wouldn’t say so; instead she’d give this snarly, bark kind of laugh that was both derisive and dismissive. She barked around Henny a lot.

Bernice, the lab technician, was the heart of the office. She had dreamy purple-blue eyes which were often red-rimmed from either allergies or husband troubles. She’d been married a few times and had a couple of kids. She and Henny often held hushed conversations in the mornings.

While the other women shuffled paper, Bernice did actual medical work. She drew patients’ blood, made slides, filled hematocrit tubes and set them in the machine to spin. Most of her day was spent peering into a microscope, identifying and counting good and bad blood cells. She showed me an example of a sickle cell once and explained that, unlike a healthy circular red blood cell, this was half-moon shaped and therefore carried less oxygen through the body.

Bernice was my direct superior. She taught me everything I had to do in the office. And though I felt low as linoleum, I tried my best because I wanted Dr. A. to think well of me.

He was smart and funny, and unlike my father, heard everything I said the first time. I wanted him to adopt me; he already had three sons, he needed a daughter. One morning he demonstrated what he’d be like as a father when a delivery guy boldly looked me up and down. Dr. A. saw this and was outraged, which I translated to mean he’d protect me from louts and any other misfortune.

Dr. A. always made a point of engaging me with some nonsense before we entered an exam room. He’d jiggle his eyebrows like Groucho Marx or tell a joke, and after I’d laughed he’d put on his serious face and tap on the door.

While he conversed with the patient, I stood by the wall willing myself invisible. His patients were usually milky pale with rumpled skin and hollowed-out eyes. From my spot at the wall I saw a woman with a surgically smoothed chest. At first I admired her flat chest, envied it almost, and then the penny dropped and I realized both her breasts had been removed. However, if she was seeing Dr. A., the disease still hounded her. She’d given her breasts to cancer but it wanted more. It made me wonder what cellular bombs were brewing beneath my own elastic skin.

During the exam he’d listen to the patients’ heart and lungs, palpate their bellies, and check the lymph nodes under their arms and at their groin if necessary. Then he’d say one of three things: how well they were doing, that they needed a blood transfusion or chemotherapy, or that Henny would arrange for them to be admitted to the hospital.

By now I was eighteen, and five days a week I watched people wheel their loved ones into offices where they hoped for good news. In contrast, my pain and confusion had no precise diagnosis though it made me stagger as I worked through the day. I struggled in silence, tamping down my despair as I tried to keep up with the new tasks added to my evolving job.

For instance, Dr. A. performed bone marrow extractions in the office. The sterilized white package, wrapped like a package from the butcher, held all the necessary items for the procedure. As I watched, he’d inject an anesthetic into the area, talk to the patient as it took effect, and then plunge a long, hollow metal needle into the patient’s sternum or hip bone. It was sort of like coring an apple but instead of apple seeds, he brought up a tube of moist bone marrow. The apparatus he used looked both barbaric and elegant. Once he’d finished, I had to clean the instrument, wrap it in white cloth, secure it, and then set the package in the autoclave, a small box like a microwave that hummed as it sanitized what was inside of it.

Bernice also taught me how to use a blood pressure cuff and stethoscope to measure a patient’s blood pressure. To start, I’d wrap the cuff around their upper arm, then support their arm as I squeezed a rubber ball that pumped air into the cuff. Once the cuff was tight, I’d set the bell of the stethoscope at the crease in their elbow, turn the knob at the base of the ball to release the air and listen through the stethoscope for a sound. The first whoosh signified their systolic pressure and, when that sound ceased, the diastolic pressure. Afterwards I’d quickly note each number. However, the sound and lack of it were often faint. Since I was unsure of what I’d heard, I’d ask the patient if I could do it again. These people were so agreeable. They were used to being poked and prodded by someone wearing a white uniform, and my costume signaled an expertise I didn’t possess. I felt awful about doing it a second time, but I had to be sure it was correct.

As if this physical intimacy weren’t enough, they next asked me to learn how to draw blood, something Bernice usually did. I guess they thought if I did it, Bernice would have more time for her other work. Since I thought Dr. A. had suggested it, I agreed to become a phlebotomist.

The morning training was held at Sinai Hospital, where I’d been born. We began with shoving a needle into an orange, which I didn’t mind. Then we moved on to people. I could hardly hold a conversation with someone and now I had to swab their skin with alcohol, tie off their arm with a rubber tourniquet, and jab a needle into them. It made my hands sweat to touch their skin as I searched for a vein. For a while I hid in the bathroom, but that strategy was short-lived; eventually I had to stick and be stuck by someone else.

As the morning continued we refined our new skill with more instruction. The needle had to be jabbed quickly to reduce the pain, but couldn’t be pushed too far or it would drive through the vein causing blood to leak into the surrounding tissue. Once needle handling was sort of mastered, the trick was to locate the vein. Men’s were easy to find–they often rise above the skin’s surface–while women’s veins often hide. The instructor told us to press our finger in the crease of the elbow until we sensed a line of resistance, i.e., the vein, and then clean the area and slide the needle in. Sounds simple enough. But veins are easily lost. They can roll, be thin as thread, or flatten out if someone is dehydrated, which sick people often are. Somehow I made it through the training.

Back at the office, Bernice wanted me to practice my new skill. She stood by as I tied a tourniquet around an older man’s exposed arm. He had dry, wrinkled skin, where once he’d had taunt muscles and a tattoo. But like a horse, I shied at the jump and Bernice had to finish it while I hid in the back lab.

Mornings Henny sorted the mail. Among the bills and letters were envelopes from the hospital, which held slips printed on pink paper. They were referred to as pink slips and were death notices. When one showed up she’d read off the name of who had died and we’d groan in recognition. However, if a cluster of pink slips arrived, the women would crack jokes in what I thought was a disrespectful manner. After months of this reaction, I came to see that they were struck by the patients’ deaths and black humor was their collective way of handling it.

Dr. W., one of the three doctors, saw the sickest patients. His face reminded me of Richard Nixon or a rubber mask version of Nixon. After I’d learned how to draw blood, he asked if I’d fill injections for his patients who needed chemotherapy. I was caught. I had the time, and if I didn’t do it Bernice had to do it and I’d already let her down by not wanting to do the phlebotomy thing, so I said yes. This new job was done in between weighing patients, getting them settled in a room, taking their blood pressure, and filing glass slides. It was also kind of fun to do.

When a patient required chemotherapy, Dr. W. would give me a Post-it listing the name or names of the medication to use. The medicine was stored in boxes in the lab refrigerator in between staff lunches and a carton of half and half. I felt like Dr. Frankenstein, pumping 5ccs of sterilized water into the rubber gasket of a tiny bottle and watching the crystals dissolve. Another med was a form of mustard gas used during WWI. The third, referred to by its acronym 5FU, came in glass ampules. The tops were pretty easy to snap off, and then I’d draw the liquid up into the tube of the syringe. To be on the safe side, I’d rest Dr. W.’s Post-it on a small tray along with the syringes.

Yet even with these precautions, I more than once filled the syringe with the wrong med. After I’d taken the tray into his office, I’d have this impulse to check the trash and if I saw a glass ampule lying on top of a paper towel instead of a tiny rubber-topped bottle, I’d hurry to Dr. W.’s office and hover in the doorway to see if he’d already given the patient the injection.

If he had, I’d back away and go into an exam room where I’d yank the used paper off the exam table and pull a fresh sheet over it. As I did this I’d think how to tell Bernice what I’d done. Then I’d lined up the stethoscope, the reflex hammer, and the prescription pads before heading for the lab.

There I’d watch her perched on her stool, her eyes plugged into the microscope as her finger tapped the counter. She’d done it for so many years she could count and listen at the same time. After I’d whispered my mistake, her finger would stop and she’d pull her face away from the microscope and take a swig of coffee. Then she’d say, “Go tell Dr. W.”

Of course I wanted her to handle it. I was the youngest member of the office, whose job description kept expanding. I made the coffee, made sure the bathroom stayed tidy, picked up after the patients, stacked magazines in the waiting room, treated everyone nicely, and screwed up the medication. I was sure they’d call the police, so I locked myself in the bathroom. I wanted more than anything to off-load the blame, but I couldn’t. I’d been moving too fast, I hadn’t triple checked the Post-it against the medicine. When someone tapped on the door, I had to open it.

Dr. W. sat in his office behind his desk. I explained my mistake. As he listened, his rubbery face lengthened. The silence that followed multiplied, had children of its own who had weddings and spawned more children. Finally, he said something like, “These people are very sick, one injection isn’t going to kill them.” I wouldn’t say he was casual about hearing this news, yet what could he do? The chemicals were rushing through their bloodstream. They’d already left the office. Obviously he bore final responsibility for my actions, but the mistake haunted me. I didn’t know how the body would react to potentially clashing meds. Would it make them sicker?

A few weeks later Henny read out the pink slips, including the name of the woman I’d given the wrong medication. The line was direct: I’d mishandled the meds and the woman had died. I was an uneducated eighteen-year-old. I didn’t know if there was a relationship between the medication and her death, and no one put me wise either way. I felt raw with responsibility and in that state couldn’t ask for clarification.

And in that darkness, came some light. Dr. A. invited me to join his family at their vacation home in upper Michigan. I was thrilled to be asked but puzzled by how little he spoke to me while we were there. Most of the time I hung out with one of his sons.

Winter passed, as did spring, and June came round again. I’d spent a year at the hematology clinic, in whose rooms I’d practiced becoming more of a person. I’d seen patients with punishing diseases come and go, and now it was time for me to go, too. Whatever romance I had with medicine died in that.

—Roberta Levine

x

x

x

Roberta Levine lives in rural northwestern Pennsylvania where she writes about art, the environment and education. She earned a BFA at the University of Michigan and a MFA from The Vermont College of Fine Arts. She contributes to Kitchn/Apartment Therapy, writes short stories, and teaches in an arts enrichment program offered through Allegheny College.

x

x

This piece took me through a hundred emotions. Excellent!

Nicely done, Roberta! What a treat to read your essay.

This is a very nicely balanced thing. It captures the way you are continuously haunted by yourself when you are young and in your first job with real responsibilities to your co-workers and others. The sequencing of the photos is good too.