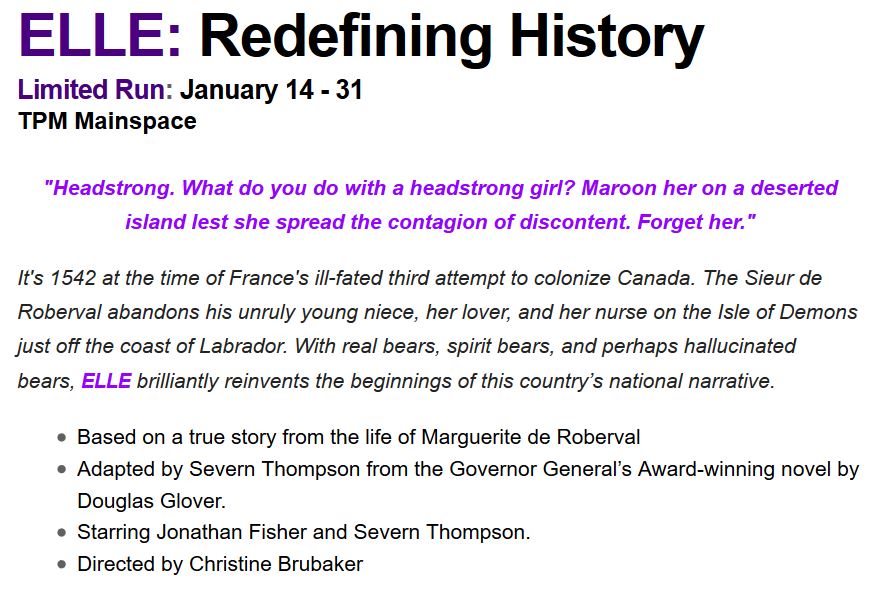

Severn Thompson as Elle, and the sheet (see below)

Severn Thompson as Elle, and the sheet (see below)

State the obvious. Elle, the novel, and Elle, the play, are distinct works of art. They are radically different forms; we have different expectations. The novel’s more than 200 pages of text suck down to perhaps 40-45 pages of script. This is necessary for the transformation into a play, a necessity and a problem for the playwright in terms of selection, but it’s not something the novelist mourns because, of course, the novel remains, fully in tact, over there on the book shelf.

In brute terms, a lot of the novel disappears. What disappears? The whole sequence of events that occurs after Elle’s return to France is gone. That means Rabelais is gone and the joke about Elle inventing the modern novel. Comes Winter, the native girl brought to France by Jacques Cartier, also disappears. Her tragic story is a dystopian inversion of Elle’s own adventure in Canada. Also gone is the frame device of the one-eyed child-stealing man and the novel’s contemporary tail with the Elle-like young woman on the beach at Sept-Iles with her older lover. These characters and devices are meant to extend the myth and the story of Elle into a larger, more mysterious cosmic rhythm beyond history. The novel is built around a complex set of themes loosely implied in words and oppositions like transformation, literary/orality, translation, New World/Land of the Dead, the invention of printing, colonization/love, and so on. Very little of this survives in the play except in stray phrases or references. Also missing from the play are the details of Roberval’s own failed colony upriver from Elle, pages and pages reduced to a few phrases and the mention of the colony’s failure. What survives in the play is a reduced set of events, a roughly similar sequence of action from Elle’s arrival in Canada to her rescue and departure for France and then, of course, Roberval’s murder in a Paris cemetery years later. The play focuses on Elle’s time in Canada and, in plot terms, becomes more of a female adventure story, Elle as Robinson Crusoe, than the novel is. Conversely, also in brute terms, a lot of the text of the play, the words, come straight from the novel. If you imagine a Venn diagram of the novel and the play, they would overlap at these points. After that, they diverge.

I say this not to diminish the play but to be clear about differences. You don’t want to make the mistake of expecting the play to replicate the novel precisely. I have listed some of the novel elements that didn’t make it into the play, but Severn Thompson’s Elle is an enactment, a presence, with a different structure and tool set, different intentions. It has actors, set, sound, lighting and a reactive audience, all in the same three-dimensional space. A novel is pure text; a play has a physicality that bleeds into the plastic arts so that on stage, moment by moment, you’re presented with tableaux or pictures that have a physical beauty. The presentation at Theatre Passe Muraille has an amazing set, starting with the what the director Christine Brubaker calls “the claw,” a metal and papier mache structure at the back of the stage that looks like the ribs of shipwreck or a dead animal or the back of a cave or the edge of a forest. It also feels like a hand, cradling the characters on the stage in front of it. This is the magic of theatre. The claw is an abstraction that changes with light, verbal context, character action, and, above all, the audience’s imagination.

Besides the claw, there’s the sheet. Oh, wonder of abstraction and efficiency. Severn and Christine needed a bear onstage and a woman changing into a bear and a way to imply that the actors are entering the world of dream. If this were a movie, there would be an actual bear. The sheet is a miraculous rectangle of cloth of indeterminate but changing colour that seems stretchy and drops into gorgeous folds. It’s a sail, Richard falling into the ocean, a robe, a tent, a flag, a hut, a fire, a bear, a sign of dream, and the face of transformation when Elle changes into a bear. There are some stunning moments with this sheet, which is sometimes on the stage floor, sometimes woven into the arms of the claw, sometimes suspended on hooks over the stage, and so on. When the white bear falls upon Elle and dies, it’s the sheet. It’s eerie how quickly the audience gets the implication, a lovely bit of theatre and timing. When the bear woman cures Elle and she drifts into a dream state, Severn the actress has her arms inside the sheet which, pulled from behind by Jonathan Fisher, the second actor on stage, creates a stunning abstract idea of a woman with golden wings. And, of course, when Elle changes into a bear, she’s draped in the sheet, again pulled from behind, so that the human face is suggested but is also bearish. She changes into a bear just by having the sheet pulled against her face and body.

There is deliberate anachronism in the play just as there is in the novel but enacted quite differently. Itslk is an Inuit hunter in Elle, the novel. He presents the intersection of European colonization and the myth/culture of native Canada. In the play, his role is expanded. Jonathan Fisher has a desk and sound board and a microphone and a guitar set up off to one side of the stage. Through the play he makes music, sings a native song, does a throat singing loop, plays the guitar, etc. He’s a contemporary native artist/musician watching the play and participating in the play and, at the appropriate moment, he comes to the centre of the stage and plays the part of Itslk. Again, theatre is physical. In the same moment, Elle is onstage speaking her lines (having sex with Richard, pleading with her uncle, crooning over her dying baby) AND the contemporary native is present just a few feet to the side with an electric guitar and a soundboard. The effect in a theatre is difficult to parse precisely because, in the audience, you are aware of the juxtaposition but at any given moment the imagination is engaged with Elle or the line. The lighting focuses you. It’s a mechanism of audience manipulation that seems marvelous to me. And, of course, there are multiple message loops: Jonathan Fisher is an actor but also an Anishinaabe musician. Also in real life he is a member of the bear clan. And he delivers one of the lines that does depart significantly from the thematics of the novel. This occurs when he is reciting the story of his mythic quest/hunt for the white bear, a quest that Elle disrupts by her presence (one of the crucial metaphors of the novel is the moment when Elle’s European story collides with Itslk’s mythic quest and destroys it). In the novel Itslk is aware, sadly and tragically, that the disruption of his story means the ultimate disruption of his culture, a moment that cannot be redeemed. In the play, Severn Thompson gives Jonathan’s Itslk a more hopeful line about the bear returning, the myth world coming back (in other words), which is a nod to the contemporary resurgence of native of culture. The novel wants the reader to dwell in sadness; the play wants to leave some hope. That aside, there is clear a moment of delight when Itslk appears. You can feel the audience shift. It’s a daring and brilliant invention, this Jonathan Fisher/Itslk character. And he gets to deliver some very funny lines, bring back the dead dog, bring back the tennis ball, and deliver the thematic legend. (It’s fascinating watching audience, BTW. When Elle throws the ball off the ship and Leon, the dog, apparently dies, the audience turns against her, faces go suddenly glum. But when we hear the dog bark off stage, glimmerings of recognition appear. And there is a wondrous delight when Itslk produces the lost tennis ball — for me, this is a bit like watching the readers reading my novel.)

Lighting, sound. You deeply enjoy the effects. The framing of the tableaux on stage and with lighting creates a monumental feeling, creates focus, creates shadow and transformation. Some images are spectacular. For example, the moment when Elle/Severn falls through the ice. Suddenly she’s illuminated by a bright filtered light from above, a column of light, that imitates the flickering, shadowy feel of being under water while the actress mimes a person drifting down. There is more of this than I can describe here. And in all these moments you see the differences in the kinds of works of art. Novel. Play. (And film, if you think about it — the play is so much a series of abstractions demanding audience interaction whereas in a movie there would be much more of the real, a real ship, a real island, a real bear. A film more often than not will try to leave less to the imagination than a play or a novel.)

A play has actors, not to be left out. Severn Thompson loved the novel Elle and saw a place for herself in it, and she is a spectacular actress. On stage every fibre of muscle is engaged in action. Her body is an instrument. She is amazing to watch. We are so used to movie and TV acting, which is mostly minimalist acting from the eyebrows to the chin (actually, on TV acting is mostly a minimal movement of the lips in speaking). The intensity of a stage play is astonishing. I saw three performances and the best audience was the third night which had an ASL component and a large number of deaf people in the audience. ASL is, of course, an enactment of language. Deaf people communicate with actions and they are acutely tuned into the physicality, the presence of the speaker. You could almost feel their attentiveness to Severn’s every move. In stature, she is a diminutive woman; on stage she is monumental and heroic (also very comic, sometimes pathetic, always passionate, exploding with energy). The lighting keeps trapping the gestures, like a series of still photographs, and they are gorgeously expressive. She’s also just a wonderful mime. With a gesture and a hanging of the head, she inhabits bearishness. She knows how a body looks drifting in the ocean. She has so much to work with in the play from lust (gorgeously funny sex scene early on, also a scene in the novel), rapture, resignation, pathos, rage, animal transformation, flirtation, and love to childbirth and the death of the child. It’s a huge part for an actress, a dream role, I would think. And Severn runs with it. Extravagantly and joyfully. I wrote the book, and I was still misting up when Emmanuel dies in her arms. Even the third time I saw it.

What else? Too much to think of. A note on structure. The novel has some little thematic pre-texts, then the frame with the one-eyed man, then the sex scene on shipboard. What the play does instead is quite fascinating. It actually opens with what you might call an overture, a montage of moments (tableaux accompanied by gong-like sound effects and flashes of light) that in fact presage the action of the whole play in gesture alone. The bear is the there, the death of the general, the death of the baby. Just a gorgeous piece of structure. Then the frame: Elle in Paris, by the cemetery, catching sight of the general, Roberval, her uncle in the gloomy street and starting to tell her story. Then the story begins, on shipboard, sex with Richard. Fleetingly, Elle steps back into the storytelling moment, once or twice, just enough to establish the frame and story together, and then we are off. We return to the frame scene at the very end of the play (these transitions beautifully indicated by a repetition of gesture, key language, also a slight costume change and a jug of wine) and thence to the final confrontation with Roberval. Throughout there are beautiful recursions, language, shape and gesture. The “headstrong girl” phrase from the novel. The shape and presence of bearishness (even Jonathan Fisher, with his fur vest, sometimes hulks like a bear). The cradling of the baby Emmanuel (at one point, again, Fisher is back behind the claw, apparently cradling a baby in his arms). It’s also interesting the way the play is text heavy through the scenes up to and including the arrival of Itslk. When he leaves and after the birth and death of the baby, the play leans more and more heavily on image. Itslk’s presence effectively introduces the native element and begins to educate Elle in the epic traditions of the new world (she is already steeped in her own epic traditions). The death of the baby and the advent of the bear woman (and her symbolic rebirth in the ocean) bring Elle into the world of dream and dream and image subsequently drive the remainder of the play, which, here, takes on a quality reminiscent of German Expressionist theatre. These are structural effects, small and large, that you notice upon revisiting the play, and you begin to appreciate the amazing physical inventiveness of theatre.

When I go to a play, I desire a total experience: intelligent interaction with characters/actors on the stage, magical and surprising effects, emotional engagement, language. I got what I wanted when I saw Severn Thompson at Theatre Passe Muraille. I wrote the book, I knew the lines, but I was still surprised and entranced. It was delightful still on the second and third viewing; I saw more, of course, and appreciated the artistry more (and was able to peek at the audience). If you can, go more than once. It’s revelatory. First reviews of the play kept mentioning that awful movie The Revenant (which, in my head, I keep referring to as The Ruminant). That is a completely wrong-headed response based on the most superficial resemblances (wilderness, survival, bear, revenge). Elle (both play and novel) is about first contact, the tremendous collision of European and native cultures, it is about an act that is continuous and ongoing, a conversation between our cultures. Because she is a woman (and a reader), Elle is the most apt and available of the Europeans for transformation. She and Itslk are paired cultural receptors; they know what is going on, the vast, tragic pageant. The Ruminant is a movie with its dumbed-down realism and a pop-Nietzschean thematic that’s very appealing to commercial audiences. It’s not the same thing at all.

—dg

“I don’t know how I went”. A slang from the rez, indicating a certain reverence, and other subtle meanings. I hope the play tours west. Wonderful! Also, funny, the Ruminant.

Will the play be touring, Doug? Gananoque has a lovely little theatre on the waterfront.

Colette, At this stage there are hopes that the play will tour. It’s up to regional theatres to get in touch with the principals and arrange to bring the play. It’s quite portable, just two actors, a few odds and ends of clothing, the desk and the claw. And the sheet. We have hopes.

There are actually two theatres in Gananoque: The Thousand Island Playhouse, which is on the waterfront, and The Firehall Theatre, which is located right behind it and closer to the street, and used to be the town’s firehall. The Firehall Theatre is smaller in terms of seats and stage, and puts on events that are more ‘modern’, for lack of a better term. Do you have contact info for Ms. Thompson or other principals that I could pass on to the Playhouse? I would love to see this play come to town.

Colette, I think the person to get in touch with initially would be Andy McKim, the artistic director at Theatre Passe Muraille. 16 Ryerson Ave, Toronto, ON M5T 2P3 Administration: 416 504 8988

I’m going to see what I can find out. Thanks for the info, Doug.

Ah, thank you, Debra. I hope you do get to see it one day. Also you got my ruminant joke. Thank you. 🙂

Congratulations, Douglas! It sounds simply wonderful!

Thank you, Genese. Hope you’re having a lovely residence.

I would imagine there is no hope that it will tour anywhere near me (or anywhere in the U.S., for that matter), but I would really love to see it. Perhaps it will be performed again in Toronto when I’m back in Massachusetts and it’s easier for me to get to Toronto. 🙁