‘This is a flag about unspoken voices”:

Nathalie Bikoro at the Pitt Rivers Museum

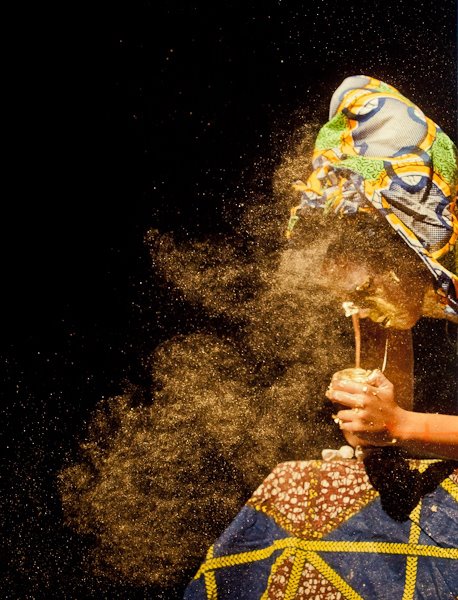

Nathalie Anguezomo Mba Bikoro chooses a place in Pitt Rivers Museum (Oxford, England) to sew a flag. She constructs this object from pieces of Dutch Wax fabric, of various colours and designs, sewn together with needle and thread. The meaning of the Dutch Wax fabric Bikoro selects (deliberately and carefully) has already been made visible in the work of Yinka Shonibare MBE (RA). The cloth, a colonial invention, that came to be equated with Africanness, calls into question the authenticity of objects, and their historical, political and cultural entanglements. First produced in Dutch Indonesia, and then later manufactured in Britain, Dutch Wax was sold in West Africa and came to be equated with African identities (both within the African continent and in Britain). In Bikoro’s performance, the cloth also has personal importance and invokes family memories and narratives, particularly those of her grandmother: “This kind of cloth made in the Netherlands and India were given as a gift to African countries. My grandmother used to say: ‘What gift? They are asking us to wear what they want us to look like.’ She was excluded from her village in Gabon because she burned the dress that she was given.”[1]Bikoro’s grandmother gave her the cloths used in the performance at Pitt Rivers. She speaks of how her grandmother told her to burn them: “I like the metaphorical idea of burning the archive. Burning is a form of cannibalism. You are eating something, projecting something new, digesting something that is given to you and creating something else with it, to then state the voices that are untold and unheard.”[2]

Photo: Jonathan Eccles, Pitt Rivers Museum

Photo: Jonathan Eccles, Pitt Rivers Museum

Bikoro is a French-Gabonese contemporary artist currently based in Berlin. Her interdisciplinary practice explores the possibilities of international dialogues across continents and communities. A ten-year battle with Leukaemia during her childhood in Gabon, the Netherlands, and France informs the narratives and methods that underpin her work and her interest in developing educational collaborative community projects. Her PhD work encompasses philosophy, cultural politics, the arts in Africa and networks between Europe, Brazil and the African continent (including Nigeria, Kenya, Cameroon, South Africa, Senegal and Gabon). Bikoro’s work and her performance and live art practices have appeared internationally, including most recently, in November, at the 7a*11d International Festival of Performance Art (2014) in Toronto.

Photo: Jonathan Eccles, Pitt Rivers Museum

Photo: Jonathan Eccles, Pitt Rivers Museum

In the Pitt Rivers Museum, in Oxford, Bikoro makes a flag, not for the purposes of a specific country, geography or political affiliation but rather for the sake of her own memories, those of her ancestors, and those who wish to enter into a dialogue with her: “I am creating a flag to contest the idea of freedom. What gives you the freedom to say how I must look, how I should speak, what my voice is? What gives you the freedom to represent me as a flag with these colours?”[3] She places herself not in the centre of the museum but rather in an unassuming spot in one of the upper galleries where visitors might choose to engage with her or not. Bikoro’s action of sewing occurs not as spectacle but rather as though an ordinary, everyday activity. She rests the fabric with which she works on a glass cabinet filled with objects and their labels: these things are obscured as she assembles her flag from segments of cloth (some of which lie on the floor at her feet).

Photo: Jonathan Eccles, Pitt Rivers Museum

Photo: Jonathan Eccles, Pitt Rivers Museum

Visiting the Pitt Rivers Museum is like time traveling: objects from weapons to jewellery are densely packed into cabinets of wood and glass or, in the absence of space, larger objects such as boat paddles are suspended from above. The museum was founded in 1884 to house in excess of 26,000 archaeological, ethnological and antiquarian objects which were given to the University of Oxford by Lieutenant-General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers (1827-1900).[4] The collection also includes objects transferred from Oxford University’s Museum of Natural History and the Ashmolean Museum, and was added to by its curators beginning with Henry Balfour: there are now thought to be about 50,000 objects on display and the collection, as a whole, consists of more than 300,000 objects (as well as a comparable number of field photographs, manuscripts and sound recordings).[5]

Photo: Jonathan Eccles, Pitt Rivers Museum

Photo: Jonathan Eccles, Pitt Rivers Museum

The reverence with which museum objects are handled, conserved and displayed is obstructed as the artist re-imagines the museum cabinet as a surface upon which to sew. Her action appears as a private ritual performed within a public space. People, including myself, gather around her. As we watch her thread needle and cotton, and stitch the cloths together, deliberately disregarding precision and allowing for asymmetries and imperfections, we ask her questions which turn into conversations. There is no barrier between us and the artist as she works: we are invited into the space she produces and we stand around and talk and look. Her performance animates the space of the museum and the objects in the glass cabinets the immobility of which render the lives which brought them into being opaque: “This comes from India. This comes from Africa. Africa is an invention. You can’t say this comes from Africa. It comes from a specific family, a specific place. These objects are also about colonial encounters and came about because of exchanges between different countries and people.”[6] Notions of invention, the fictive and the mythical are alive in the narratives embedded within the Dutch Wax fabric, and its circulation as commodity and locus of identity. The idea of invention is brought to life in the spoken exchanges with Bikoro which complicate the meanings of the objects in the cabinets, and the labels and systems which attempt to structure and contain how it is we experience them.

Photo: Jonathan Eccles, Pitt Rivers Museum

Photo: Jonathan Eccles, Pitt Rivers Museum

Bikoro’s action of sewing a flag enters into a dialogue with Pitt Rivers Museum from the perspective of her own history and subjectivity which she brings to its atmosphere, its aesthetic, and its curatorial approach. Across from her performance is an installation of film and sound. The event as a whole is titled Les Statues Meurent Aussi II a direct reference to the 1953 film Les Statues Meurent Aussi (Statues Also Die), directed by Chris Marker, Alain Resnais and Ghislain Cloquet. This film places the idea of the colonial collection, and the display of historical African art, under scrutiny and its opening credits acknowledge the support of institutions and individuals which include ‘Mr. le Colonel Pitt Rivers’.[7] Bikoro’s film installation (composed of two films projected onto two separate screens) appropriates footage from Les Statues Meurent Aussi aspects of which were filmed in General Pitt-Rivers’s’ private collection held at Farnham in Dorset. The film was first screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 1953 and subsequently banned by the Centre National de la Cinématographie from 1953 to 1963 (despite being awarded the Prix Jean Vigo in 1954).[8] It was commissioned by Présence Africaine, a literary review and publishing house founded by the Senegalese writer and editor Alioune Diop, established in 1947.[9] Many of the most significant Francophone thinkers and writers on négritude – including Aimé Césaire and Léopold Sédar Senghor – are associated with Présence Africaine. James Clifford reflects on Césaire’s négritude which, situated in relation to Caribbean history, presents the possibility of an ambiguity that ‘keeps the planet’s local futures uncertain and open’.[10] Clifford asserts that: The “Caribbean history from which Césaire derives an inventive and tactical “negritude” is a history of degradation, mimicry, violence and blocked possibilities.”[11] It is also he adds “rebellious, syncretic, and creative.”[12] He concludes: “There is no master narrative that can reconcile the tragic and comic plots of global cultural history.”[13] Bikoro’s practice is cogniscent of histories and discourses of colonial violence (and her own ancestral links to these) and she works to open up dialogues, with those who encounter her work, in a manner that is neither didactic nor oppositional. Her film installation deploys the devices of avant-garde film encompassing montage and multiple (apparently incongruous) narratives staged simultaneously. She deliberately disrupts linear, causal narration and an unfaltering faith in objectivity and empirical evidence: historical events are deliberately muddled and obscured and merged with the artist’s own memories and experiences (sound includes that of her baby’s beating heart).

Photo: Jonathan Eccles, Pitt Rivers Museum

Photo: Jonathan Eccles, Pitt Rivers Museum

Despite appearing frozen in time the museum embodies, albeit on the surface largely opaque, a number of museological approaches and histories. Jeremy Coote (Curator and Joint Head of Collections) narrates: “It is not simple, unilinear history. The museum, the way it is now, has not just developed in a single line.”[14] The glass cases were manufactured and brought in at different times from the nineteenth through to the twentieth-first century, and until the 1960s the roof was glass: ‘The museum was full of light because it was all about rationality and enlightenment. This was about the scientific approach to understanding human technology’.[15] In the 1960s the glass roof was replaced because of the damage caused to organic objects by light. Also in the ‘60s the displays were considered old-fashioned and irrelevant to anthropology (the university wanted to move the museum out to another place). In the 1980s anthropologists again began working on art and material culture, and museums and representation: ‘People began to find positive value in the way the museum was. It preserved certain aspects of museological practice. It had a certain atmosphere. Gradually we have become aware that it is in part an aesthetic that we are preserving.’ [16]

To animate the objects in the museum, and to breathe life into them, requires acts of dialogue and performance. No object is ever really frozen in time or space, no museum display of glass, or descriptive label can immobilise meaning or the narratives, contingencies of time and history, and acts of imagination people bring to things. This is the importance of Bikoro’s performance, which is a political strategy alert to dialogue, conversation and the affective and subjective significance of sites of historical and cultural memory and exchange. As viewers, we see the film, hear the sound and watch the performance only for a short time and then it is over. It exists only in our memories fashioned by what we choose to remember or forget: “I am sewing a wound, an old wound. This is a flag about unspoken voices.”

—Yvette Greslé

Nathalie Bikoro, ‘The Uncomfortable Truth’, live performance, November 2011, duration: 40 minutes. Curated by European Performance Art Festival, Warsaw (Poland). Documentation: courtesy of EPAF Warsaw and the artist.

Nathalie Bikoro, ‘The Uncomfortable Truth’, live performance, November 2011, duration: 40 minutes. Curated by European Performance Art Festival, Warsaw (Poland). Documentation: courtesy of EPAF Warsaw and the artist.

Yvette Greslé is an art historian and writer. She was born in Johannesburg, grew up in the Indian Ocean archipelago of Seychelles, and now lives and works in London. She is an editor at Minor Literature[s] founded by Fernando Sdrigotti and her blog ‘writing in relation’ represents the political issues and questions that propel her work forward as a whole. Yvette’s PhD research, based in History of Art at University College London, explores traumatic memory, historical events and video art by South African women artists. She is a Research Associate at the University of Johannesburg and has written about contemporary art for publications in the UK, Europe and South Africa.

- Interview (Nathalie Anguezomo Mba Bikoro and Yvette Greslé) Pitt Rivers Museum, 11 October 2014.↵

- Interview (Nathalie Anguezomo Mba Bikoro and Yvette Greslé) Pitt Rivers Museum, 11 October 2014.↵

- Interview (Nathalie Anguezomo Mba Bikoro and Yvette Greslé) Pitt Rivers Museum, 11 October 2014.↵

- Cootes, J. ‘Speaking for themselves’, www.ahi.org.uk, Pushing Boundaries, Spring 2011, Volume 16, Number 1, 22-23.↵

- Ibid. 22-23. I have also drawn from email conversations with Salma Caller (Education Officer, Adults, Secondary Schools and Communities at Pitt Rivers Museum), 10 and 28 November and 1 December 2014.↵

- Interview (Nathalie Anguezomo Mba Bikoro and Yvette Greslé) Pitt Rivers Museum, 11 October 2014.↵

- Les Statues Meurent Aussi (Ghislain Cloquet, Chris Marker and Alain Resnais, 1953) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hzFeuiZKHcg↵

- Les Statues Meurent Aussi http://sensesofcinema.com/2009/cteq/les-statues-meurent-aussi/↵

- Les Statues Meurent Aussi http://sensesofcinema.com/2009/cteq/les-statues-meurent-aussi/↵

- Clifford, J. The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge: Massachusetts and London: England, 1988), p.15.↵

- Ibid.p.15.↵

- Ibid.p.15.↵

- Ibid. p.15.↵

- Interview (Jeremy Coote and Yvette Greslé) Pitt Rivers Museum, 11 October 2014.↵

- Interview (Jeremy Coote and Yvette Greslé) Pitt Rivers Museum, 11 October 2014.↵

- Interview (Jeremy Coote and Yvette Greslé) Pitt Rivers Museum, 11 October 2014.↵

Simply lovely vision and words. Thanks for this piece.