Harlequin’s Millions is the long recollection of Bohumil Hrabal, the last of three novels from the late Czech writer that bear witness to the unrecounted histories of a family, a people, and the passage of time, illusory and elegiac in form, it is a momento mori of unbroken, dreamlike prose that captures in remembrances the reticent waiting of old age, set to Riccardo Drigo’s airy, Pucciniesque serenade, from which the title derives, with all the rhythm and repose of a forgotten love song, wistful and nostalgic. —Sebastian Ennis

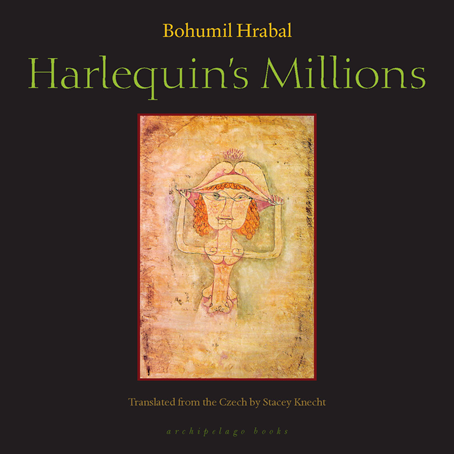

Harlequin’s Millions

(Harlekýnovy Milióny by Mladá Fronta, 1981)

By Bohumil Hrabal

Translated from the Czech by Stacey Knecht

Archipelago Books, 2014

.

Harlequin’s Millions is the long recollection of Bohumil Hrabal, the last of three novels from the late Czech writer that bear witness to the unrecounted histories of a family, a people, and the passage of time, illusory and elegiac in form, it is a momento mori of unbroken, dreamlike prose that captures in remembrances the reticent waiting of old age, set to Riccardo Drigo’s airy, Pucciniesque serenade, from which the title derives, with all the rhythm and repose of a forgotten love song, wistful and nostalgic.

Originally published in 1981 and translated for the first time into English with this 2014 Archipelago Books edition, Hrabal’s requiem for the temps perdu concludes the interwoven story he started in Cutting It Short and The Little Town Where Time Stood Still. Yet Harlequin’s Millions officially made it to print some years before these earlier works, which were banned under the communist regime after the invasion of Czechoslovakia by troops from the Warsaw Pact. Hrabal chopped up and edited bits of text from The Little Town, which was not published in its “unedited” form in Prague until after the Velvet Revolution of 1989, disfiguring the tone and, to a great extent, the meaning of the text, and leaving intact only the human face of the times. But it is the very humanity of the text that makes Harlequin’s Millions so powerful. Josef Škvorecký, the celebrated Czech-Canadian writer, said of Hrabal’s entire oeuvre that, by its miraculous existence alone, it was a critique of the social categories of his day because his characters were “triumphantly alive, they displayed the politically incorrect classlessness of raconteurism.”[1] This is no less true of Harlequin’s Millions, which is essentially a dirge for “old times,” but which receives its dissident quality from Hrabal’s timeless portrayal of the human spirit in all its eccentricity.

Harlequin’s Millions is set in a small castle that is now a retirement home, an edifice of crumbling plaster and exposed masonry ravaged by time, the façade of which belies the aura of any past decadence, changing shape within labyrinthine blocks of prose—Hrabal does not break up his chapters into paragraphs and he favours the comma over the period—to resemble the “the faces of each and every elderly pensioner” in their weary likeness, silent and motionless, to the bare, ruinous exterior. Inside lies a broken wrought-iron clock with limp, crossed hands, forever stuck at twenty-five past seven, a reminder to those waiting for the bell toll of the middle hour that their lives are stuck in the interval between life and death, because, as the unnamed female narrator tells us, everyone here knows that “most old people die in the evening, at just about half past seven.” And within this darkly comic lapse of time the soft melody of “Harlequin’s Millions” unravels and winds its way around the castle’s uncanny grounds, pouring out of rediffusion boxes that are hung not only in the corridors of the castle, where each note trails after wisps of cheap perfume, but also in the trees in the park, trickling down leaves like morning dew, and everywhere it casts its spell upon the pensioners, who are witnesses to the old times of the inescapable serenade.

As the music plays on and on, the story of an ex-brewery manager’s wife unfolds, her toothless, wrinkled face recalling little of her former beauty as she wanders through the castle grounds, distant and reproachful, looking back upon her life in the little town “where time stood still,” which can be seen from the windows of the retirement home. The unnamed woman bears the unremarkable qualities of old age and is defined only by her past, which the other pensioners guiltily acknowledge, gaining a certain pleasure in seeing her come to such an end. In her reverie for the old times, we learn of her unfaithfulness to the little town where time stood still, leading up to her escape, a sojourn in Prague where she bought a perfumery beyond her stature, only to return, broken spirited, with unsold cases of those sweet-smelling bottles and soaps that ward off old age, souvenirs of her failure. “[L]ike a severed cord whose ends had been tied together again,” her time in the little town now seemed endless. After the war, the workers took control of the brewery and fired her husband, and that once severed rope grew taut around the little town that was now part of an endless cycle of progress, hopelessly longing to return to a better time.

In the retirement home, there are three other “witnesses to old times,” who, for the brief moments that they share in the laughter and forgetting of their own histories, become the young men of their pasts once more, while other times, with the faintest trace of life left in their voices, they chronicle the old folk tales and the daily eccentricities of their long forgotten neighbours. And always they tell their stories to the unnamed woman, a narrator of true invention, as if speaking unto memory itself, so that, under the spell of the narrator’s toothless voice, the castle becomes a place of memory and fantasy, isolated from the changing times. Stories of bacchic ecstasy erupt from a poverty of spirit reserved for the elderly alone, or perhaps it is the narrator’s own boredom, her sad triviality, that causes her to bring to life in the half-lives of the pensioners the scenes of erotic love and violence that are portrayed in the castle’s fresco-lined ceilings.

Reality sets in, however, as the past is made manifest and the old graveyard of black marble gravestones and golden crosses that the castle overlooks is unearthed. The pensioners with the strongest nerves watch with tears in their eyes, reminded of all they were torn away from when they entered the retirement home, their houses, their homes, their front yards and flower beds, as the granite tombstones are pulled from the clay “with the perseverance of a dentist trying to pull a molar with crooked roots out of swollen gums,” for the roots of the trees had grown deep within the ground and wrapped around the coffins. “I myself had the feeling that, once again, all my teeth were being pulled out,” the narrator reflects, “slowly, one after another, in the morning my teeth had grown back and it started all over again.” I return constantly to this image. An endless cycle of having your teeth pulled, all that is lost in life and in death forgotten, and memory’s soft melody plays on without us.

“What is life?” the narrator asks. “Everything that once was, everything an old person thinks back on and tells you stories about, everything that no longer matters and is gone for good.” It’s fake teeth and the ones that get pulled, the past we leave behind and the stories that take its place. Reality and fiction are woven together in Harlequin’s Millions to tell a beautiful story of the unequal battle waged between life and death, and the human spirit that remains in the remembrance of the past.

—Sebastian Ennis

.

Sebastian Ennis is a future law student living in Vancouver. He has a background in Classics and contemporary French and German philosophy.

- Škvorecký, Josef. “Introduction” of Cutting It Short and The Little Town Where Time Stood Still. London: Abacus, 1993, x.↵

Huzzah! Another outstanding review from Mr. Ennis.