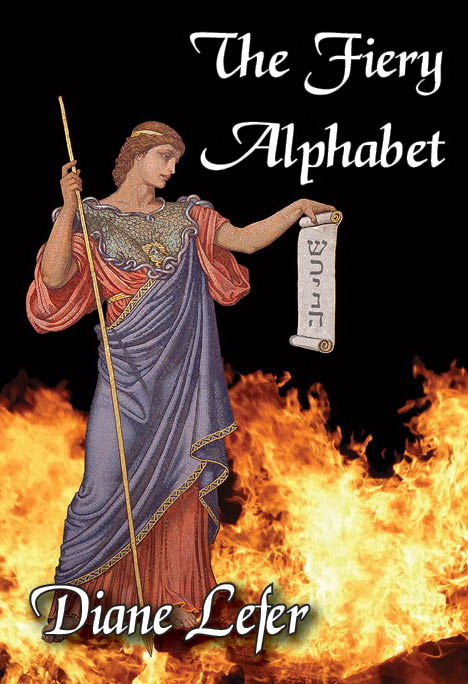

I have a weakness for the smart girls of history, and Diane Lefer has invented an amazingly smart, innocent (yet bold) 18th century Italian girl, a mathematics prodigy, hidden away in her father’s home till Balsamo, the spiritualist fraud, comes to rescue her (sort of) and wrest from her the occult numerological secrets of the ancient Jews. Just out with Loose Leaves Publishing, Diane’s new novel The Fiery Alphabet is a road book, a little tour of the esoteric philosophies of the age, and a peek into a young woman’s heart — presented as a faux document discovery the author made in her research (see author interview here). The excerpt presented here plays a bit on the combination of Daniela Messo’s naïveté (she offers herself to Balsamo but doesn’t quite know the “form” of seduction; she mis-identifies Jesus as the old man who pooped on the floor) and her brilliance with tenderness and a gently comic irony.

Diane is a dear, old friend of mine from the days when she taught with me at Vermont College of Fine Arts. She as a multiple recidivist, having contributed over and over — works of beauty, passion and commitment — to the pages of Numéro Cinq; she is one of the old guard.

dg

If I had not been raised to be a genius and if Pope Benedict had lived a few more years, my father would not have suffered a stroke on the afternoon of April 14, 1760, my thirteenth birthday. If not for the events of that day, we would not have cut ourselves off from the world, here behind these walls.

If Papa had been in good health four years later, when you first asked to be admitted to our home – a stranger, a Sicilian, without introductions or name – I suspect he would have said no. Instead, he heard your request and looked up for a moment. “Library?” he repeated. “Uh, yes,” and returned to his breakfast, a mush of bread and eggs.

If we had not been trying to save my father’s life and restore his lost youth, we would not have stood before one another naked. Perhaps I should never have reached the point of knowing I would do whatever you might ask.

“Give yourself to me,” you said, and it was as though one of Leibniz’s monads, independent and oblivious to every other monad moving through space – unaware that Pope Benedict and my father, the integral calculus, the deadly man in scarlet cap were all part of the harmony – should suddenly step back and see the entire pattern that brought you to me and made you my destiny. Balsamo.

Give yourself to me, you said. But how is it done? I am willing, don’t you see? I stepped into your arms as easily as I would hand Fiammetta a shawl, and yet I saw you weren’t satisfied. How does one give?

You can give someone a plate of noodles, but then the noodles must be eaten. It is not enough for the gift to offer no resistance – I offer none to you – but it must be offered in a form in which it can be consumed.

The problem: I am not a serving of pasta, nor a pair of lace cuffs that I can give you and even help to fasten at your wrists, an ornament to accompany you in the world.

The solution: I give up my suspicions, I hold you first in my heart and in my mind. I have entertained your friends and I have trusted you with my father’s life. Yet none of this is useful, none of it in the proper form. I have failed you.

This morning, I went to your room.

So much has happened in these short months since you first appeared. I remember you, a slight figure in threadbare clothes, a Southerner, and not quite civilized. Your dark curling beard, your hairy frame made me think of a malnourished satyr. I felt sorry for you then, you were so ugly.

This morning I sat on the edge of your bed. “I love you, Balsamo.”

“Dani,” you said, “you are so innocent.”

“Ignorant.”

“No. Innocent,” you said. “Who are you, Daniela? I want to know you.”

And I started to cry, because you do know me. No one knows me as well as you.

“You keep your secrets, Daniela.”

I have no secrets. I stood before you naked. Not even I have seen myself as you have seen me. I have looked at my arms, my thighs; I studied my breasts as they grew. But I have never seen myself whole. Only these fragments, this part, that. My face in the mirror. Balsamo, no one but you.

No, this is all wrong. I sound like a silly girl and that, above all, is what I am not. Try again.

* * *

God may not watch the world from on high, but I do. A third-story window leads onto the roof and I have scrambled over the tiles to my flat and secret hiding place and I have looked out over Rome. Here, from our house on the hill, while I look down on the church of Santa Francesca and the convent, the bell tower rises in the distance, almost on a level with my eyes. The ruined arch at the near end of the church seems to be getting higher, growing up to poke through the screen of trees. If the arch means something – and Balsamo says it does – I swear I know nothing about it.

Daniela Messo was my mother’s name and what they called me at birth. But I have no mother. I am Minerva, sprung forth with a yell from my father’s skull. He raised me to be a genius, though I have been called other things. Now, at seventeen, I cannot be counted a prodigy anymore, so what am I to be?

I am what I know. So put it all down, Daniela. Then mystery must yield to study, and fears to facts.

“When I think of all I tried to create in this world,” my father once said, “your mind is the one unqualified success.”

That mind has conquered Latin and Greek, chemistry, the integral and differential calculus. I have never before turned it to look at my life.

* * *

My father, Don Michele Messo, is a very good looking man – slender, small and well-defined. His nose comes to a sharp point and his eyebrows form two straight silver lines. His eyes glinted like metal when we bent our heads together over the secrets of algebra and geometric forms, but now those eyes are nearsighted enough to be gentle and dim. My father has always been a non-conformist – perhaps because his only child is a daughter and not a son – yet his bearing is – was – that of, I imagine, a military man. Before his health failed, he had the most wonderful way of standing up from his chair. He never unfolded his body the way some, especially taller, men do. Counting on nothing but the strength of his thighs, he would push himself up, without effort or hurry, his back absolutely straight.

Even before his stroke, I can remember, now that I think back, his memory had become confused. One day, in the spirit of radicalism, he told us – the servants Carlo and Fiammetta, and me – that we were to call him “Michele” from that day forth. We were embarrassed, but he insisted and so we agreed. “Michele,” I said, trying to get his attention. “Michele?” But perhaps he had not heard the word spoken without its preceding respectful Don since he was a boy. At any rate, he had forgotten the sound of it and no longer answered to his name. “Father,” I said at last, and then he looked up and scolded me for my formality.

Papa taught me at home. By the age of seven, I was fluent in Latin and French and could read and translate from Hebrew and Greek. I learned philosophy, and so I could have reminded my father that matter is neither created nor destroyed. He has not made me – at most, he has recombined my elements.

In those early years, I wasn’t kept here at home. I was free, or so I thought. I made my own choices though, now I see, all with the aim of pleasing him. My ignorance of Art is an echo of Papa’s disdain. We agreed that busts of the Emperors glorified tyranny; graven images of saints, gods and angels sprang from disordered minds. In the old days, by which I mean before I was thirteen, my father would call for the carriage and we’d visit his friends – priests, mostly; most every man in Rome is either a beggar or a priest. To dress respectably, even my father often wore a black cassock, and we would go and visit somber homes and palaces, vast, ill-lit and dreary, with bloody crucifixes on every wall, tables covered with bric-à-brac and pretty clocks and stones, and prayer stools arranged so cunningly that a child couldn’t help but trip over them in the dark.

Once, at a time when I could not have been more than two or three, I remember a room where murmurous women petted me and made me stand before the crucifix, looking up at the ragged, punished man upon the Cross. “And you know who He is, don’t you?” they asked, as they kissed me and fussed. I’d had no religious education. The only Cross we had at home hung over our door so that men relieving themselves in the street would show respect and squat a little further down the road.

“She doesn’t know,” the women murmured. “She’s just a baby, a tender babe.”

Even at that age, I was used to being praised for giving answers and didn’t like being treated as a child. “I do know!” I cried. “I do!”, and guessed: “That’s the dirty man who made caca on the floor.”

I can remember quite clearly the women’s shock and my own feelings of shame, but I only know the words themselves because my father loved the story and repeated it many times, but only to the most discreet and trusted friends.

—Diane Lefer

————————————–

Diane Lefer is a playwright, author, and activist whose recent books include a new novel, The Fiery Alphabet, and The Blessing Next to the Wound: A Story of Art, Activism, and Transformation, co-authored with Colombian exile Hector Aristizábal and recommended by Amnesty International as a book to read during Banned Books Week; and the short-story collection, California Transit, awarded the Mary McCarthy Prize. Her NYC-noir, Nobody Wakes Up Pretty, is forthcoming in May from Rainstorm Books and was described by Edgar Award winner Domenic Stansberry as “sifting the ashes of America’s endless class warfare.” Her works for the stage have been produced in LA, NYC, Chicago and points in-between and include Nightwind, also in collaboration with Aristizábal, which has been performed all over the US and the world, including human rights organizations based in Afghanistan and Colombia. Diane has led arts- and games-based writing workshops to boost reading and writing skills and promote social justice in the US and in South America. She is a frequent contributor toCounterPunch, LA Progressive, New Clear Vision, ¡Presente!, and Truthout. Diane’s previous contributions to NC include “What it’s like living here [Los Angeles],” “Writing Instruction as a Social Practice: or What I Did (and Learned) in Barrancabermeja,” a short story “The Tangerine Quandary,” a play God’s Flea and an earlier “Letter from Bolivia: Days and Nights in Cochabamba.”

So engaging! Love the Not a serving of pasta line! The caca on the floor! Always so much energy in Diane’s writing. Can’t wait to read this.