1. The Cairo Souk

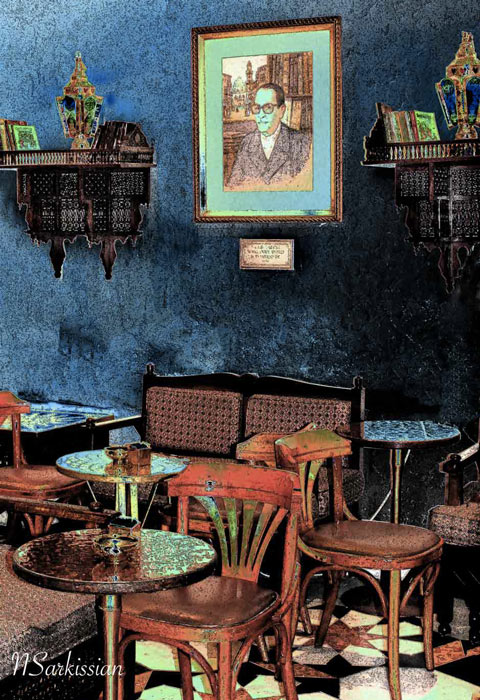

Last summer I was in Cairo, where my husband goes on business, and took the opportunity to investigate the Khan el-Khalili souk and the neighboring El-Gamaleyya district, a medieval Islamic section of the city celebrated in the work of the Nobel Prize-winning Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz. My second day in the city, I toured the Sultan Qala’un funerary complex with its polychrome mosaics and then on to the Naguib Mahfouz Café where Mahfouz had sat, the manager assured me, drinking tea, observing and writing. Now a plush restaurant operated by Oberoi hotels, the Café caters to the wealthy tourist and, as a result, has been emptied of the characters that would have appealed to Mahfouz.

2. Hotel: Poolside

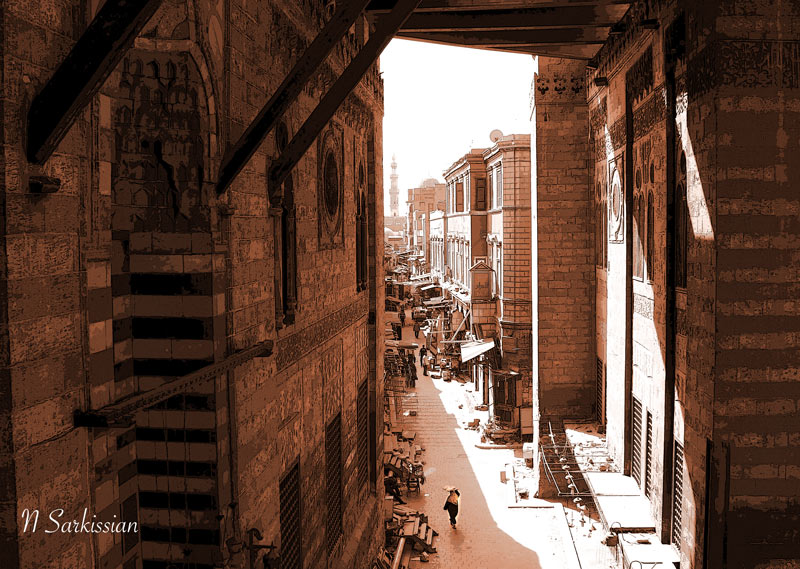

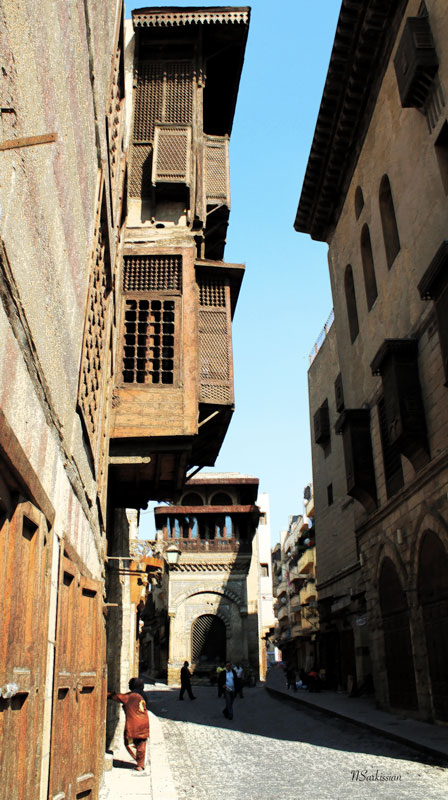

Later, poolside at my hotel, I began to read Mahfouz’s Palace Walk, the first volume of the 1500-page Cairo Trilogy (1957-1959), the saga of three generations of the Abd Al-Jawad family. The section of Cairo where I’d just spent the day unfolded on the pages before me — its enigmatic views, shadowed arches, spindly minarets, latticed balconies.

The novel paints a claustrophobic picture of a middle-class Egyptian family set against the backdrop of World War I and the First Egyptian Revolution (1919), a time when Egypt was struggling to overthrow foreign (British) occupation. Al-Sayyid Ahmad Abd Al-Jawad, the forty-five-year-old despotic head of his family, demands blind obedience from his wife, Amina, and their five children. Inside his home, he enforces strict rules of Muslim piety; yet outside, he indulges all manner of indiscretion. Amina’s submission and her later clumsy attempt at emancipation from her philandering husband form the main plot line of the novel.

Hence, in the opening pages of Palace Walk, Mahfouz places thirty-nine-year-old Amina, married at fourteen and sequestered behind the walls of her house ever since, inside a latticework balcony. It’s midnight, Amina has just woken as she does every night to wait for her husband to return home from his evening out with friends, to help him out of his clothes, to wash his feet and otherwise serve him:

“She seemed to be in a hurry as she wrapped her veil about her and headed for the door to the balcony. Opening it, she stood there, turning her face right and left while she peeked out through the tiny, round openings of latticework panels that protected her from being seen from the street. (Palace Walk, London: Black Swan, 1994, 2)

Mahfouz depicts the street but filtered through Amina’s eyes; she has been indoors for twenty-five years, an experience that has deformed her ability to comprehend what she sees, and the landscape reflects this:

To her left the street appeared narrow and twisting. It was enveloped in a gloom that was thicker overhead where the windows of the sleeping houses looked down, and less noticeable at street level because of the light coming from the hand carts and from the vapor lamps of the coffeehouses and the shops that stayed open until dawn. To her right, the street was engulfed in darkness. There was nothing to attract the eye except the minarets of the ancient seminaries of Qala’un and Barquq, which loomed up like ghostly giants enjoying a night out by the light of the gleaming stars. It was a view that had grown on her over a quarter of a century. She never tired of it. The view had been a companion for her in solitude and a friend in her loneliness during a long period when she was deprived of friends and companions before her children were born, when for most of the day and night she had been the sole occupant of this large house with its two stories of spacious rooms with high ceilings, its dusty courtyard and deep well. (2)

Not only does the landscape envelop her, but it acts upon her, crushing and eluding her. She gazes at it with love, but she can’t know and experience it. She’s confined, rendered dependent and fearful.

As a result, Amina looks for solace in prayer:

When she was left alone, her only defense was reciting the opening prayer of the Qur’an, sura one hundred and twelve, about the absolute supremacy of God, or rushing to the latticework screen at the window to peer anxiously through it at the lights of the carts and the coffeehouses, listening carefully for a laugh or cough to help her regain her composure…true peace of mind she would not achieve until her husband returned from his evening’s entertainment. (3-4)

Only once, when she was younger, did she complain:

It had occurred to her once, during the first year she lived with him, to venture a polite objection to his repeated nights out. His response had been to seize her by the ears and tell her peremptorily in a loud voice, “I’m a man. I’m the one who commands and forbids. I will not accept any criticism of my behavior. All I ask of you is to obey me. Don’t force me to discipline you…. She learned from this, and from the other lessons that followed to adapt to everything…in order to escape the glare of his wrathful eye…she had no regrets at all about reconciling herself to a type of security based on surrender. (4)

3. The Souk: Revisited in Person and on the Page

The next day I went back to the souk so I could take more photos. I told my guide, Fahdi, about Mahfouz and asked what he thought about latticework balconies and veils. About to answer, he was interrupted when his phone rang. I could hear a woman’s voice through the receiver. She was agitated. Fahdi shot me an embarrassed glance, and then clicked the phone shut. “My son is acting up,” he said.

Then he answered my question. His wife doesn’t live under lock and key, but a woman should wear veils, especially once she’s married. Shortly thereafter, as we traversed the goldseller’s street, a young woman with her child on her hip shouted after us. Fahdi translated. “She wants you to put on a scarf,” he said.

In Mahfouz’s fiction, tradition doesn’t only constrain the women; men too are firmly grasped. In Palace Walk, Amina’s husband, Abd Al-Jawad feels compelled to act with solemnity in front of his family. Crossing the threshold of his home, he stifles the smiles and laughter he freely bestows elsewhere; this he does to safeguard his dignity and authority. He ascends the staircase toward his bedroom long after his children have gone to bed; no one except Amina knows he has been out carousing. He signals his arrival by beating the steps with his stick. The sharp sound spurs Amina to action, she holds a lamp over “her master’s” head so he can see where to walk.

But unlike Amina, Abd Al-Jawad may come and go at will. As he sits in his bedchamber allowing his wife to serve him, he reflects on the evening he has just spent in the company of others.

It was nothing for him to journey a long way, to the outskirts of Cairo, in order to hear a renowned male vocalist like al-Hamuli, Muhammad Uthman, or al-Manilawi, wherever he resided. Thus their tunes found shelter in his hospitable soul, like nightingales in a leafy tree. He loved song with both his soul and his body. (10)

This momentary return to the world outside often produces the tendency in Abd Al-Jawad to be kind to Amina; he confesses his innermost thoughts, or speaks to her about the war (WWI) or the revolution, “thus making her feel, if only for the moment, that she was not just his servant but also a partner in his life.”

To the world outside, Abd Al-Jawad is charming and fun, very much involved in the life around him. He owns a bustling grocery store that opens on a busy street in the heart of the souk. This store represents an aspect of his public persona; its openness, fullness and bustle clash with the rigidity of the domestic landscape and his private demeanor. Noise from the endless flow of passersby, hand and horse carts, singing vendors chanting about their tomatoes, doesn’t interfere with Abd Al-Jawad’s concentration as he reviews his ledger. Instead, the landscape operates on him, increasing his equanimity. Friends and customers freely enter, stop to visit. He receives his share of respect and esteem but above all else is loved “for the charm of his personality more than for any of his many other fine characteristics.” The store also provides a haven in which Abd Al-Jawad meets his lovers:

He was bent over his ledgers when he heard a pair of high-heeled shoes tapping across the threshold of the store. He naturally raised his eyes with interest and saw a woman whose hefty body was enveloped in a wrap. A white forehead and eyes decorated with kohl could be seen above her veil. He smiled to welcome a person for whom he had been waiting a long time…the electricity was hidden and silent but needed only a touch to make it shine, glow and burst into flame. He seemed to be expecting this visit which was an answer to whispered hopes and suppressed dreams. (390)

But he is not infatuated with women for themselves, rather:

He was infatuated with feminine beauty in all its flesh, coquetry, and elegance…tens of [his] women had all possessed at least some of these characteristics. (390)

Nor is he wracked with guilt:

At times he recognizes what he is doing is wrong, but he cannot imagine viewing life in any other fashion than the way it appears to him. (413)

4. Hotel: Poolside, 2

Later at the hotel pool I watched a man taking pictures of a pretty girl in a headscarf. She sat on a lounge chair, stood under a palm, leaned against a column near the hotel’s in-house shisha stand, changing outfits twice. I wondered if she were modeling for a publication. Perhaps she was on her honeymoon.

I ran into her an hour later in the ladies’ room. Her scarf lay on the counter. Her curly black hair was twisted into a sweaty knot at the top of her head. She doused her red face with cool water, then stared at me in the mirror. “I’m so hot,” she said in perfect English. “I like your hair.”

5. The Souk Again: The Mosques of Al Husayn and Al-Azhar

The next day, on my way to the Mosque of Al Husayn, the holiest shrine in Islamic Cairo where the prophet’s grandson’s head is said to be buried, I asked Fahdi about the girl.

“She must have been a rich girl from Jordan,” he said.

We parked near the square and Fahdi left me by the women’s gate while he went to the men’s entrance with my husband. I twisted a scarf around my head.

Leaving my shoes in a cubbyhole at the door, I slipped into hooded, floor-length robe I was handed. Women sat against the walls, holding children, listening to the sermon piped in from the men’s section. Others formed a line at a doorway leading to the interior; through the arch I could see the top of a large, elaborate silver sarcophagus.

Midway through Palace Walk, while Abd Al-Jawad is away on an overnight business trip to Port Said, Amina’s children suggest she make a covert visit to this holy place, a place she has always longed to visit. With her children watching, her face lights up; she contemplates the trek and what it signifies:

It was as though an earthquake had shaken a land that had never experienced one before. She did not understand how her heart could answer this appeal, how her eyes could look beyond the limits of what was allowed, or how she could consider the adventure possible and even tempting, no—irresistible. Of course, since it was such a sacred pilgrimage, a visit to the shrine of al-Husayn appeared a powerful excuse for the radical leap her will was making, but that was not the only factor influencing her soul. Deep inside her, imprisoned currents yearning for release responded to this call in the same way that eager, aggressive instincts answer the call for a war proclaimed to be in defense of freedom and peace. She said in trembling voice,” A visit to the shrine of al-Husayn is something my heart has wished for all my life … but … your father?” (165)

Her children convince her to go; her youngest son Kamal escorts her. She marvels at the streets and shops she passes along the way, her heart beating faster as she and her son draw ever nearer:

They walked around the outside of the mosque until they reached the green door. They entered, surrounded by a crowd of women visitors…. She proceeded to devour the place with greedy, curious eyes: the walls, ceiling, pillars, carpets, chandeliers, pulpit, and the mihrab niches indicating the direction of Mecca…. The slow moving flow of women carried them along until they found themselves near the tomb itself. How often she had longed to visit this site, as though yearning for a dream that could never be achieved on this earth. (167)

But on her way home, feelings of guilt submerge Amina’s joyful elation; she faints in the crowded street and breaks her collarbone. When her husband discovers what she has done, he banishes her. An outcast, she languishes at her mother’s, shamed as a chastised wife. She realizes that her dream of change and freedom was one that ‘could never be achieved on earth,’ a lament that echoes the wider political struggle of the time with early twentieth-century Egyptians despairing to be freed of foreign domination.

After she has despaired of ever returning, one day she is summoned home. Friends and neighbors have intervened on her behalf. Her husband forgives her and she is allowed to resume her old life. Blissfully content, she resumes her lawful demeanor within the confining walls of her dwelling, having attained nothing lasting.

In a parallel action later in the novel Abd Al-Jawad attends a mosque for Friday prayers and comes face to face with his transgressions.

The sermon directed his attention toward his own sins, sweeping aside all other considerations. He found himself directly confronted by them. They were given such terrifying vividness by the penetrating and resonant voice of the preacher that al-Sayyid Ahmad imagined he was singling him out and screaming into his ears at the top of his voice. He would not have been surprised to hear the preacher address him by name: Ahmad, restrain yourself from evil. Cleanse yourself of fornication and wine. Repent and return to God your Lord. (412-413)

But such considerations do not produce any sort of long-lasting change for him either; Abd Al-Jawad asks for pardon, forgiveness and mercy but never repentance; he cannot imagine life flowing any differently than the way it does. Quitting the mosque, he resumes his old ways.

Standing in line, thinking about the book, quietly observing and snapping a few discrete pictures, I reached the banister surrounding the tomb of Al Husayn. Beyond, I could see my husband and Fahdi, far away on the men’s side. They waved to me. I waved back.

6. Coda

By establishing a system of oppositions from which his characters are unable to escape, Mahfouz increases their conflict and fragmentation. From a historical point of view, the portrait of the Abd Al-Jawad family is an accurate depiction of the late 19th, early 20th -century Egyptian middle class engaged in a struggle for independence that has lasted in many ways until the present time.

But times have changed and absolute subservience of wives to their husbands has largely been replaced by a position of near equality. Mahfouz charts the developments of the Egyptian marriage relationship in the two successive volumes of the Trilogy: Palace of Desire and Sugar Street. Nevertheless, a hidden life of repression still governs both men and women. Women may drive cars and vote, but many still wear veils; these seem to function in a manner similar to the latticework balconies wives once hid behind.

Winding through the alleys of Cairo, below spiky minarets and through shadows redolent of dust and decay, Mahfouz’s words rang in my ears. We emerged into Tahrir Square, the heart of Egypt’s Arab Spring. In the throng of men, I could see Amina’s great granddaughters, in veils, protesting.

–Natalia Sarkissian

Great work, Nat … you transport us through time and across miles with such elegance. And I love the final shot best …

Thanks, Martha. So lovely to see you here!

Fantastic!! article! Photographs are illuminating. Wonderful writing. Numero Cinq is publishing

first-rate material.

Wonderful literary article and fantastic photos – made me feel I was there.

Nat thank you for this beautiful piece – I have never been to Egypt but was captivated by The Palace Walk many years ago. What a lovely confluence of circumstances, time and place, transporting indeed – reading your essay and musing on the evocative photos, with echos of Mahfouz’ prose. It sent me back to my bookshelf, and I realise that I must have lent volume 1 of the Cairo Trilogy to a perfidious friend (or left it in a hammam?).

I too have never visited Cairo and I haven’t yet read Palace Walk, but after this thoughtful article, I

plan to do both. Thanks for the inspiration. What a fine writer you are!

Laura, Ralph and Elizabetta,

Thanks for your wonderful comments. So glad you enjoyed the essay and the photographs. It was a privilege to tour Cairo and be able to see the area Mahfouz describes so eloquently in his novels.

Natasha

Lovely essay and stunning photographs. Your voice is an echo of the past. Love the veil and lattice metaphors. So impressive.

Thanks Deb!

Your striking and beautiful photographs plus your plot summary took me right back to my first reading of Mahfouz’s trilogy many years ago. Wonderful. Thank you. Yes, I hope Amina’s grand-daughters are right out there in Tahrir Square!

Cynthia, thanks for stopping by and for commenting! I’m glad to know you enjoyed the essay and photos.

I really enjoyed the article. I have many of Mahfouz’s books in Arabic, and have visited most of the places you photographed. Very nicely written!!

I wish I knew Arabic so I could read the originals. The translations are good~but one senses that something is lost. Thanks for reading and commenting, Hussein!

Just finished reading “Palace Walk”. Lovely review and beautiful photographs! I visited Cairo over 10 years ago, so your photos provided a great refresher for me having just finished a masterpiece of a book.

Thanks for reading and commenting. I’m glad you liked the photos. I wonder how much you’d find Cairo has changed if you went back for a visit?

Natalie,

Loved your essay! I lived in Egypt from the end of WWII until just after the Tri-Partite Aggression of 56. Your comment of some women “still wearing veils” could also be written “again wear veils”. In the 50s & 60s veils were rare in Cairo save among country folk visiting the city!

Will

Will, what a fascinating period you spent in Cairo and thanks for this comment.

Thank you for the pictures and the article Natalia. I’ve just reached mid-way in Palace Walk and wanted to see if there are any visuals of the street, the latticed windows, the shops, the minarets online, and I’m glad I came across your article.

I notice that your surname is Sarkissian – very similar to the Circassian (Turkish) dish prepared by Zaynab in Palace Walk. 🙂

I too am mid way through the novel and am enthralled by it. I have loved seeing your photos which have brought the streets of Cairo to life for me whilst reading. I like your analogy of Egypt being under the domination of the British, like the family are under the domination of Al-Sayyid Ahmad. Its made me want to visit Cairo sometime!