Stephen Curry (Photo: Rebecca Cook/Reuters via Scholastic)

Spring 2009

THREE RANDOM EVENTS came together in the space of a short time that struck me as having some connection, or at least holding that possibility, or at any rate stuck with me at a time not much else was sticking, and thus I thought worth a stab at an essay.

The first was a quotation from Terry Eagleton’s review of a recent biography of William Hazlitt, posted by a colleague, out of the blue and without comment, on our department listserve:

From William Blake to Oscar Wilde, art was an image of what men and women could become in changed political conditions. They, too, could be gloriously pointless; in fact, this was the whole point of human existence, which the gray-bearded puritans and chill-blooded champions of the work ethic had never understood. Human beings resembled works of art in being ends in themselves.

Mention of Hazlitt reminded me of a another chance encounter. Several weeks before, and I can’t think of anything that might have prompted me, I reread his essay “The Fight.” I hadn’t read much Hazlitt, all of that back in graduate school at Berkeley thirty years ago, and it was assigned reading in a course on Romantic literature. The essay didn’t leave much impression then, other than being personal, unsubstantial, and rather precious.

The third event, a week later and utterly unrelated, was going with my son to see Davidson play Saint Mary’s in the second round of the NIT. I’m a Davidson alumnus who lives in San Jose, and the game, in Moraga, was only seventy miles away.

The Eagleton post came during exam week, a time when many of us are weary, students and teachers alike, and may question what we have accomplished the past weeks, the value of our efforts. I’m a college English instructor who teaches largely composition, and what the post made me wonder is if I and others in the discipline haven’t missed the point. Most of our attention is directed to correctness of varying sorts, measurement, and critical placement and reception at the expense of imagination and the human spirit that should inform what we read and write. The liberal arts are supposed to liberate us, not wear us down

Hazlitt’s essay is about a fight he attended nearly two hundred years ago between Bill Neate and Tom Hickman, aka The Gas-man, two champions of the time. The contest was a major event, drawing by one estimate around 25,000 and on which, according to Hazlitt, some two hundred thousand pounds were wagered. Social codes dictated that it be fought away from the city, in rural Hungerford, about as far away from Hazlitt’s London as Saint Mary’s was from me. The essay, in fact, is considered a classic, but on rereading it my initial impressions remained. Hazlitt spends most of his time recounting the arrangements he had to make, on the fly, getting there and back, and his talk with his companions along the way. His assessment of the fighters largely rests in his disdain of Hickman’s arrogance, of their performance, in his preference for stand-up knock-down fighting, which he got. The text is sprinkled with literary allusions that seemed forced and quaint. His language still didn’t stir much from me, other than some sideways glances. As to the fight itself, a long one, he only gives a few pages.

Yet he has great respect for both fighters and his enthusiasm charges the piece, and on my second reading I found it exciting. And it touched on and fed the excitement I felt about going to the Davidson game. Davidson is small school in North Carolina, noted for its academics but which athletically can’t compete with larger schools. Last year, however, its basketball team made an extraordinary run in the NCAA tournament, losing to Kansas in the quarterfinals, who went on to win the tournament. Davidson’s success was attributable in large part to its star guard, Stephen Curry, with whom the nation fell in love and who led the nation in scoring this year. I introduced Curry and the rest of the team to my son, who took an interest in them as well, and we followed them as best as we could, largely through box scores and YouTube clips. Few games were broadcast nationally until the tournament.

This year, however, Davidson lost in the second round of the Southern Conference tournament, thus losing their automatic bid to the NCAA, and although they won their season title easily and had a record about the same as last year, they were not selected at large. It was a very competitive field this year and many teams were left out, including Saint Mary’s in the West Coast Conference, whose guard, Patrick Mills, an Australian, played for his country’s team in the 2008 Olympics, who gave our NBA squad a run. Mills, like Curry, of modest height and slight build, at least for basketball, but spirited and savvy on the court, has also received much national attention. Mills, however, broke his hand during the season, leading to a few unexpected losses, enough to keep them from getting a bid as well, even though he had recovered by tournament time. As always the NCAA selection committee showed a decided preference for the large conferences over the mid-majors. So there was great excitement in the Bay Area over the Curry-Mills match-up, along with the sense of being slighted, perhaps some frustration over the power size can wield. Tickets sold out in less than an hour.

Not many Davidson fans live out here, however, and as an alumnus I was able to apply for tickets through the Davidson athletic office. When I got them my excitement rose several degrees, which surprised me. My son was really excited, too. I could tell—when he’s excited, his face becomes a closed, expressionless mask, clamping down on what he feels within, maybe because he’s overwhelmed, more likely because he doesn’t want to lose any part of it. Little stirs me that much now and I started looking for explanations, maybe contexts, or at least a way to contain my excitement.

There are always contexts. Hazlitt, Eagleton tells us, was a man of letters, a public critic, belonging to that species of English writers who were conversant with several disciplines and kept tabs on cultural events high and low. They were also politically engaged and wrote for a general, middle-class public, as well as for those in power, both of whom listened and could be swayed by their opinions. Eagleton doesn’t mention “The Fight,” but presumably by writing about lower-class fighters and praising them for their strength and courage, Hazlitt elevated their status and, by extension, that of others at the bottom, thus might have drawn sympathy and given them greater consideration in the politically oppressive environment of nineteenth-century industrial England. I read a critical study of the essay by David Higgins, who notes that Hazlitt had personal issues to attend to as well, which his essay helped shore up. Going to the fight and writing about it must have been restorative acts.

“The Fight” is a personal essay, and whatever Hazlitt’s motives, it was important that he put himself in the frame. The value of the fight comes not just from its implied contexts, public and private, but also from his actual presence there and his experience of it, what he saw and felt, and what he shared with his companions. But experience is not a single, isolated act. The anticipation, the going, the witnessing, and the returning are all parts that determine any experience, which helped make the trip, in his case, a “complete thing,” as he says at the end.

I want to do something similar, talk not just about the Davidson game but also about my journey there, up and back, and try to locate myself, and reach out for contexts, and maybe see what else I can find. I may have some shoring up to do as well. There will be differences. It was a basketball game, not a fight, that I attended, and I didn’t go to see anyone get knocked down. I will spend most of my time with the middle class and a largely male world, though I am still not sure what either designation means. And while I may raise a few, I won’t rest with any moral assessments. Life, like basketball, is not a matter of standing one’s ground and taking blows, or shouldn’t be. Most, I want to preserve the game and players. We forget our athletes quickly.

The essay will be personal and pointless, though perhaps not gloriously so. If it serves any purpose, it might be to encourage readers, as many as can, to write about the experiences that move them and where they put them in the world, and about the people they share them with, to find ways to preserve all these before they are lost. There may be a larger point in that.

Style, in part, is a matter of negotiating one’s sensibilities with those of one’s audiences, not all of them friendly, and often is a battle where one has to compromise or cut one’s losses. I need to do more background reading to appreciate fully Hazlitt’s essay. Some humility is in order on my part as I think about the fights I’ll lose with readers now and in the future. But also writers can only do so much, and there are things we can only point at but not capture. I can only state flatly, and I’ll do it here, that my son and I stood and shouted full throat almost the entire game, wholly absorbed in a spirit that was not hysteria. I have never felt closer to him in my life.

There was nothing quaint, however, about Hazlitt’s fight. Back then boxers fought barehanded without a set number of rounds and kept fighting until one was knocked out or his corner threw in the towel. In the twelfth round Hickman took a blow that left him thus:

All traces of life, of natural expression, were gone from him. His face was like a human skull, a death’s head, spouting blood. The eyes were filled with blood, the nose streamed with blood, the mouth gaped blood. He was not like an actual man, but like a preternatural, spectral appearance, or like one of the figures in Dante’s Inferno.

.

Saint Mary’s warned me that parking would be tight, so we left mid-afternoon, hours early, to make sure we’d get a space and avoid traffic. More, I wanted to make an event of the trip, giving us time to unwind and walk around the school, which I hadn’t seen before. Also, Christopher is a senior in high school, still undecided about next year, and while Saint Mary’s isn’t in the picture, I thought it might do him good, for comparison elsewhere, that he saw the college, too, and got some sense of campus life.

But we got stuck in traffic anyway, all the way, in the 280/680 push to Sacramento, which kept both of us quiet, leaving us to our separate thoughts..

One of the factors that has shaped my life and which has gotten progressively worse is the hassle of going from A to B, the stalls, the noise, the urgent, massive crowding. The freeway was rough everywhere, with cracks and patches and asphalt warps, reminders we might be living on borrowed time. Still, the scenery was pleasant once we put the Silicon Valley sprawl behind us, the bare, softly rolling hills, fully green from winter rain, soothing and sensual. Yet the hills would turn dead brown in the coming rainless summer, as they always do, and it was hard not to think of grass fires, the Oakland fire, mud slides, and earthquakes, the faults beneath the smooth veneer of the California landscape.

Traffic, of course, is not a big deal and it is much worse elsewhere. We get used to it and put this irritation aside. It would be madness not to do so. Earthquakes seldom are a big deal either, and most who have lived here long enough don’t pay much attention. We learn to roll with the punches—this is what defines the California character—yet after thirty years I still haven’t settled in, and each time I feel a tremor something inside me slips a bit.

I wonder what else we have inured ourselves to, with what effects.

I am worn out and dispirited, for personal reasons I won’t bore anyone with. I will, however, look outside. Part of the problem, mine and ours, as with freeways, is the size and complexity of the facilities and institutions that determine the course of our day-to-day lives, the distance, separation, and simplifications—and chaos—these can cause. But I haven’t heard much discussion about issues of scale, and our solutions tend to larger schemes.

An enormous amount of money has poured through Silicon Valley the last decades without beneficial effect on its environment or the quality of its life and culture. Now many of us are scrambling, and if we took the time to leave the freeways we would find more of us are doing much worse. Yet all these years, prosperous and lean, the state has gone through a series of budget crises, the current one the worst. Services have been cut, the infrastructure left in varying states of disrepair. Public schools have endured perpetual hiring freezes, layoffs, program cancellations, and increases in teacher loads. Like earthquakes, budget shocks have become a permanent part of our economic climate. But that cannot be a problem of size but of priorities, or of something else we have not looked at and factored in.

I have taught at seven schools, three of them with some reputation, and the experience has not been wholly rewarding. Faculty at all are competitive and contentious, the departments specialized and divided. Not only is there no mechanism in place to give support and recognize basic needs, the language does not exist to express them. The humanities can be less than human, and sometimes inhumane.

I am not alone. Many I know of my age, in teaching and in other professions, here and throughout the country, are in the same shape and they voice similar concerns. Like me, they didn’t see the malaise coming.

Further out, a war that was supposed be quick and decisive, which was entered without much resistance and continues into its seventh year, whose wanton violence has fatigued on the screen of our attention. The Iraq war was not planned and the last administration’s motives, at best, were naïve and simplistic, yet which, from appearances, were sincere and, for all I know, based on the purest of beliefs. But if we judge it by its actions, we find behavior that is only semantically—and politically—removed from war crimes. The war itself has had no other results other than gross loss of lives and resources. Meanwhile our national economy, after several large stutters the last decades, has collapsed. All the signs had to have been in place for some time—why didn’t anyone see this coming? The investment decisions we are discovering now leave us incredulous, the bonuses that lost track even of the joy of greed, the complicated schemes that proved blind and self-destructive. But belief has not been exercised well in a culture that is ramped up, self-absorbed, and unreflective. Again, the problem cannot be size. I don’t think any of us know what we are doing.

All the above needs support and qualification, but I fear doing so would just wear me down more and I would lose the course of what I want to say. There is so much to untangle, so much that makes it difficult just to state the obvious. I also need to move further out into the world and add to my list, but that might make me lose heart altogether, and heart is what I’m trying to save.

.

We only had to make a few turns off the freeway before we left traffic and drove on narrow, winding roads, first beneath the shade of oaks, then out into vacant fields and the gentle foothills. It’s easy to forget what an open place California still is, but you don’t have to drive far to find it. We arrived hours early and had plenty of time to walk around the campus. It was a gorgeous day of saturated colors, the full blue of a cloudless sky, substantial yet transcendent, and the several rich greens of the trees and hills and well kept lawns, against which stood in sharp contrast the school’s mission revival architecture, the accent of red tile roofs, the crisp planes of the plastered walls of the buildings and the lattice of connecting arcades, bright white.

Like many older schools, Saint Mary’s was located in a secluded setting, reflecting the belief that education should provide a protected environment where knowledge and values could be preserved and students have a chance to develop before they entered a world that would tug at both. Like many, it has a religious foundation, Christian Brothers, evidenced throughout—a chapel that looks to Italy, banners in one arcade with pictures of the Brothers who were past presidents, and, in Oliver Hall, the main dining room where we ate, a crucifix, which set Christopher and me a bit on edge. The mood seemed relaxed, but there weren’t many students out and the school was very quiet, even in Oliver, where I was hoping for the robust exhalation of student life. The precise geometry of its layout suggested a theorem we didn’t feel we should dispute, so we kept to the walks and stayed off the grass. But I should reserve speculation. I later learned it was mid-term week. Besides, late afternoon is not a fair time to look at anything.

I reveal, of course, my own background. What the contrasts jogged were memories of my own days at Davidson, which I completely put behind me the day I graduated, thirty-four years ago. Having Christopher with me also helped as I thought about what kind of life he might have ahead, as he must have been doing himself, though he made no comment. This was new territory for him and I suppose he was sorting things out. There is so much I want to tell him about education and what it might mean for him, now and later, little of which he will listen to. In part, he doesn’t know all the language, but also such matters are the last things on the mind of a seventeen-year-old. I didn’t think about them that much when I was his age, in fact am still putting my thoughts together now. Besides, I am his father. I never listened to mine.

Davidson College was established by North Carolina Presbyterians in 1837, sixteen years after the Neate-Hickman fight. Located in a town of the same name, now virtually suburban Charlotte, twenty miles away, Davidson, the school, when I started in 1970, had a student body of about a thousand guys, and Davidson, the town, was not much more than a sleepy main street that soon gave way to rural land and Southern forests. Then a French professor could be seen sitting in a barber shop next to a farmer, and at the time they might have got the same haircut. Its architecture made a nod to classical influence, largely through columns and pediments on almost every building, but the buildings were functional, sparsely ornamented, and not especially convincing yet not imposing either, almost all built of North Carolina brick, whose subtle yet solid colors I miss. They were not ugly. The Presbyterian campus church, like the religion, was refined yet modest and unassuming. We walked wherever we wanted and were loud when we ate.

The school was late letting go traditions and requirements many schools had at one time. It still was not yet coed and mandatory chapel and ROTC were dropped only a few years before I started. The Vietnam war was still on, however, and student deferments had just been eliminated, so most of us signed up for ROTC anyway—I didn’t. The school taught us to think well of ourselves, but not highly, and had an honor code in place we took seriously. The emphasis was on hard work, trust, and respect for culture and cultures. A two-year humanities sequence, taught by faculty from all disciplines, was heavily promoted and most of us enrolled. It wasn’t a party school and had a subdued fraternity presence through eating clubs that weren’t especially selective. Tuition was not cheap, but it wasn’t a select destination for private high schools. No social distinctions were made, of if they were, they were ignored. After the eating clubs, the library was the primary social gathering place. But Admissions liked well-rounded students and we had many high school athletes. When we weren’t eating or studying, we were out on the playing fields, acres of them, all in constant use. We had, I think, fifty intramural basketball teams in winter—it was the only way to get to play indoors, at Johnston Gym—but I’m not sure the number wasn’t closer to a hundred.

Politically it was not conservative but progressive, a qualified term. Service, however, in youth groups and the public schools in Davidson and the other small towns nearby, was encouraged and taken up. What I most regretted was what Davidson most lacked, a streak of wildness, the spark of some inspiration. There were only a few artists and a couple of fairly tepid radicals, on the faculty, no famous scholars or writers. As for products, the school turned out mostly professionals—lawyers and doctors and businessmen, a good number of Presbyterian ministers, a handful of public servants and academics, and a few soldiers—men not looking to reshape the world but find and solidify their position in it. In short, it was a middle-class school, though with notable exceptions on either side.

Needless to say, Davidson was the last place I wanted to be, and my four years there were my penance for not making my mind up about what to do with myself. I felt like an outcast and was moody and complained the whole time. Meanwhile the world outside, with its madness, its brightness, its complex urgency, to which the school seemed oblivious, raced away from me at an accelerating pace as it recreated itself in all directions, leaving me behind.

Yet I liked the guys and we all got along. The professors were accessible and we visited many homes. My freshman faculty advisor, Alden Bryan, Chemistry, introduced me to the music of Poulenc. The honor code was based on trust in us—we were allowed to schedule our exams and take them in classrooms without proctors—and gave us a standing in the school that helped define our relationships among ourselves. We didn’t lock doors, didn’t fight against each other to get ahead, and if anyone cheated, I never heard about it. We talked about what we studied late into the night because it engaged us. I haven’t since seen an atmosphere as close or supportive, at Berkeley or at any of the schools where I’ve taught.

And I did get a good education. The various disciplines, all of them, were not seen as adornments or hurdles to leap before we moved on, but as fields to be respected in themselves, whose importance did not have to be defended. I didn’t take the humanities sequence—how could I have an economics professor teach me Shakespeare?—but I missed a larger purpose. Disciplines should be brought together to provide a broad context and allow arguments to go back and forth. Those who study and teach the separate fields need to come together as well and see where they might stand in some larger order. At the very least, we need to realize we all have a stake in our culture, like it or not. But most, we need to find a way to define ourselves that we can live with. The humanities touch on all that makes us human, a point lost in a world that tends only to recognize our special technical abilities and our particular impairments, physical or mental. Most discussion now only goes back and forth between these two, and it’s hard to believe that our focus on the first is not a cause of the latter.

But I did study broadly. I read a great deal of literature, across the board and back, as well as had concentrations in philosophy, psychology, and art. So many places, so many peoples, so many customs and societies, so many hopes and fears and crimes and redemptions and failures and pathologies and abominations, so many ways of picturing these, of explaining them, of maneuvering through or around them, so many emotional curves set against the world by which I might gauge and set my own—it would take twice as many years to review and analyze all that I saw and thought about, or more. I also took a course in comparative religion, taught by the formidable George Abernathy, who put all the religions, East and West, on equal footing and maintained for each the same distance and respect. Such a vast and bewildering array of creation myths and eschatologies, and all the rites and ethical practices that led from one to the other, the different hells and heavens, the possibility in the East there was neither—the course, in all the differences and contradictions it presented, as much challenged the terms of faith as opened up its possibilities.

One shortcoming in my studies, and another of my complaints against Davidson, was that they didn’t recognize how special I was. What I learned were the special ways how I wasn’t special. That was liberating. In general, I learned perspective, or the need for one, and the many terms on which it might be based. I discovered different angles of approach and different means of expression, different ways to handle all the urges and oddities and genuine desires I found, inside myself and out, and give them some kind of life. I also learned to be open as well as maintain distance and reserve. There is too much we couldn’t figure out in the past and still haven’t settled now, too much that gets lost whenever we define it. Perhaps the world was moving away from me, but I discovered other worlds that preceded it and lay its foundations, for better and for worse. The present one did not hold all the options in life or all the answers to our problems, no matter how much it claimed it did. Nor is there is anything wholly consistent or absolutely hierarchical about our past cultures. They offer more varied—and more interesting and even wilder—arguments and contradictions than the ones we look at today. Most, I started to find a place on which to stand, but I also learned a way to stand alone.

It is a sober assessment I give of Davidson, but then again that is what the school trained me to do, and I take measured joy in making it. And in many ways the education I received—we all received—was that of the public critic.

Eagleton, in his review, laments that public critics have lost their influence with a general audience and those in power, that opinion is now shaped by “the political technocrat, P.R. consultant, and university don.” Policy is reached by seduction and direct manipulation, not by two-way public talk. As for the first two voices, I suppose an argument of expedience could be made. Those who have our best interests in mind best know how to shape our opinion quickly and effectively to get the best results. Assumed, of course, is that they have our best interests in mind and that we are incapable of making good decisions ourselves or even knowing what our interests are. Yet there is nothing in their means of discourse that can help them decide themselves what our interests are, unless they have some other way of thinking to guide them. But this is what frightens me most: what if they believe that the techniques of manipulation and seduction are the only means of discourse, or that manipulation and seduction are the discourses that best define our best interests, that manipulation and seduction are the message? As for the university specialists, their advice is determined by how well a plan fits within their particular field, most likely to the exclusion or in ignorance of others, and is couched in a specialized language few of us, policy makers or followers, can understand. In such a reduced rhetorical environment, any other voice that tries to make an appeal based on our humanity, in its complexity, its oddness, its richness, not only will not be considered, it won’t even be understood—by anyone, leaders or followers, dons or manipulators alike.

Education teaches us how to read the world and is what builds leaders and followers. There has been a lot of talk about the importance of education in our society, but not enough over what should comprise it—or why. Most emphasis has been on math and the sciences, along with literacy, narrowly and sterilely conceived. A college degree has also become a bald requirement, unquestioned, for just about any job that will lead to a stable, comfortable life and is about the only way to secure a position of influence in our society. Much has changed, but higher education is still largely a middle-class affair. While the middle class has been the target of much cultural criticism, not much critical thought has been directed at how it should see itself and what it might do. The middle class does have power and can provide the voice of concern, of common cause, of responsibility and trust, of engagement in all that keeps our culture relevant and vital, but only if taught how and encouraged to do so.

Maybe Davidson graduates were not out to change the world, but they have tried to keep it intact. As I read the monthly alumni journal, I see that a great many fellow graduates are involved in their churches, and their churches are involved in the community. Many are socially conscious and active, this work done in their professions or on top of it. Given recent events, I want our investment bankers to be graduates of such a school. If we’re going to have soldiers, and we will, I want them to come from Davidson. When I went there the accomplishments of Lieutenant William Calley and his superiors in My Lai were still fresh in mind.

.

We went to get our tickets early, but found that once we got them we had to go in, and that once in we couldn’t leave. The game was two hours away and I wanted to come back later, but Christopher was insistent we not wait. So we went with the handful we met at the Davidson will-call table to find our seats, up on the second level, two rows behind, as we discovered later, the Saint Mary’s student section.

Compared to the mammoth stadiums for the NCAA tournament, McKeon Pavilion was a modest setting, sparse, functional, and small—3,500, maybe more with some crowding. The ceiling hung low above the court and seats ran close to its sides. The arrangement was open seating on unmarked benches without backs or numbers, slots that would have to be defended if we wanted to keep them. Already many were coming in, claiming theirs. On one end, some ten feet away from the court, a bare, cinder brick wall, unpadded. Whatever happened there was going to be personal and intense.

I talked to two of the guys who came up with us, one a bushy-bearded man, quite modest but quite stout, quite robust, and quite Anglo Saxon, now living in Santa Cruz, who introduced himself as Ben Allison’s high school coach in England, Ben our backup forward. I can’t decide if Hazlitt’s gusto was part of his constitution, but it might have been of the other. He was a younger grad from Miami, his family Cuban once, maybe, who had flown all that way to see the game. His interest in the team could be read on his face, and I liked him a great deal. We talked about the regular season, the differences between this year’s team and last, about the game coming up. Others around us, Saint Mary’s alums, noting our Davidson t-shirts, shared a few words as well, and I overheard private concerns about what they might be facing. They could only have known our team from what they had seen on television last year.

Later we saw our team walk by a side door in street clothes, including—Stephen Curry!

Nothing else going on.

All this time to kill—I got tired of sitting and asked Christopher if he wanted to take turns holding our seats so one of us could walk around. Christopher, however, was settled and told me to go ahead. He wasn’t going to miss a single thing and wanted to be sure he was there when it happened. He’s a spirited kid, for whom patience is still a ways off, yet when he is moved, he is moved wholly, of which his stillness is one gauge. I admire this absorption and hope he finds a way to keep it. He may also have enjoyed the wait. Anticipation is not a pleasure I ever learned. And he remained seated the entire four hours, while I got up and left three times.

But more than excited I was restless, my restlessness fed by growing doubt. The team’s success was one of few upbeat events in my life the last year and I had invested too much of myself in it, which, of course, is a mistake. I also thought they were going to lose, though I don’t know if my foreboding came from what I knew about the team—they had stumbled the last weeks of the season—or from my own uncertainties about myself projected onto them. What I find now is that I don’t know how to handle idle moments. It is then that all that I manage to put aside, in the interest of moving forward, returns to the surface. Or maybe this is when I realize that moving forward is the illusion, superficial, discovered by standing still.

I finally left and walked around, making a pit stop I didn’t need, then went to concessions to get some coffee. There I ran into a fellow graduate from my class whom I didn’t know well at school and talked to him briefly, suffering the proverbial shock of time—hairlines, girth, etc. Miami showed up and while we talked Andrew Lovedale walked by, not yet in uniform, having taken a wrong turn somewhere, maybe. I didn’t recognize him and it was Miami who pointed him out. I expected him to be a foot taller. Lovedale, from Nigeria, was our center and the physical and spiritual anchor of the team. He looked worried himself, though he may have only been building resolve. He’s not the kind of player who takes anything for granted.

When I returned to our seats, Max Paulhus Gosselin, starting guard, from Quebec, was out on the court, alone, practicing outside shots, not looking sure of himself and missing several before the moil of a gathering crowd…

.

As to why I was so taken by the team, it helps being a graduate. But also it was a team who beat the odds, one reason I wanted Christopher to know the guys as well as why they caught my attention, along with the nation’s. We love our alma maters, eventually, and while we make life hard for our Davids, we love them when they emerge. Not only is amateur basketball a national passion, crowded and highly competitive, from city court pickup games to high school tryouts to the traveling AAU teams to the hundreds of colleges arenas, it is also big business, where players who hope to turn pro are not the only ones who stand a chance of making serious incomes and where large sums of money pass, not all of it above the table. In such an environment Davidson can’t compete when it comes time to recruit, especially not in the middle of ACC territory. The school is not attractive to players with ambition as the Southern Conference is not strong and doesn’t offer them a national spotlight.

Davidson did enjoy a brief surge in the less crowded ’60s, thanks largely to the recruiting wizardry of Lefty Driesell. When he left, however, the program languished, and faculty talked of moving the team down to Division III. But then the school hired Bob McKillop, twenty years ago, who slowly turned the program around, and in the last years Davidson won many Southern Conference titles, thus making several NIT appearances and playing four first-round games in the NCAA, all with low seeding though a few of them close. What a scrappy team—was probably the only notice the team received and the guys were soon forgotten.

Then there was 2007-08. After close losses to highly ranked teams early in their schedule, they raced through the Southern Conference regular season and tournament without a loss, earning a better seed in the Midwest bracket of the NCAA. First they came from behind and beat Gonzaga in the last minute, Gonzaga the West Coast Conference winner with almost the same roster that won the title over Saint Mary’s this year and from whom much was expected in the NCAA. Then they overcame a 17 point deficit in the second half against Georgetown, the regular season winner of the Big East who, towards the end of the season, was ranked in the top ten. Next they ripped through Wisconsin, Big Ten tournament winners and another top ten team.

But the game that impressed me most was against Kansas. It wasn’t Curry’s best game and the Kansas defense effectively shut him down the last ten minutes. Aside from Curry, Davidson didn’t have a single pro prospect; Kansas had five players taken in the NBA draft. Davidson should have been blown out, yet they controlled the pace and stayed with Kansas all the way. A win here would have put them in the final four against UNC, against whom Kansas racked up a 28 point lead in the first half, almost the same Tarheel squad who won the NCAA this year, and who only beat Davidson by four points earlier that season.

The image that stays with me is of Bill Self, the Kansas coach, kneeling on the sideline, anxious, with the huge Detroit crowd stirring in anticipation as Curry brought the ball down with 17 seconds to go, the team down by two, everyone waiting for, expecting, what we all knew Curry could do effortlessly from 30 feet in—

How did they do it?

What does their success mean?

The players were in good academic standing and very much a part of campus life. I would like to argue that the team’s wins were a reflection of the school and that they validated its character and purpose. Not all of us can make it on sheer talent or raw physical ability, and strong minds and identities have to count for something. I wouldn’t pretend to claim those are prerequisites, however, that gifted players have to prove themselves in the classroom before they can make a career from their gifts.

Davidson did have skilled players, though their abilities were not enough to attract the larger schools. Jason Richards was a very fine point guard, who led the nation in assists, and not all of his passes went to Curry. He could bring the ball down the court against tough defenders and run the offense effectively. Commentators praised him for his basketball intelligence, his ability to see the court, read defenses, and find openings. He could also shoot outside and did what no one watching could quite believe, make a slight hesitation in his drive, then charge past larger, faster defenders, who should have held him, and score an easy layup. In the four tournament games, he averaged 9 assists against only 2 turnovers and 13 points a game. The sprightly Bryant Barr, a pure shooter with a double major in math and economics, came off the bench the second half and hit three threes in a row against Kansas to keep Davidson in the game. Box scores never showed the contributions of Gosselin or Thomas Sander. Gosselin (“The Pest”) was a tenacious defender against any player of any size; Sander set effective screens for the shooters and was a presence under both boards. Also he was tough—he played almost the entire tournament with a broken thumb, suffered in the first game against Gonzaga.

Size is another problem for small schools, especially now that basketball has become more physical, the players muscled up. But Sander, along with Lovedale, Boris Meno, from Paris, and Steve Rossiter, all around 6-8, gave Davidson the heft it needed to stand its ground against the larger teams. Lovedale is the one who impressed me most and whom I most admire. He grew up in Nigeria and went to school in Manchester, England, where McKillop found him. His father, pushing school, did not allow him to play sports, and Lovedale didn’t start basketball until his father died and his mother relented, some five years before going to Davidson.

Andrew Lovedale (AP Photo/Chuck Burton via livescience)

He is strong in all the ways a man can be strong. His face is a study of conviction and determination, echoed in a body that is muscular from the top down, his strength one of definition, not bulk, its assemblage one of coordination. Everything he did on the court, down to the smallest execution, was filled with purpose, and when he drove for a dunk or went up for a rebound, it was like watching some absolute force unleashed that I want to call moral. He could stand up against any player and not be moved aside. Yet he also showed great speed and agility when he guarded outside the paint, where, with quick steps and a powerful winding of arms and legs, intense and unrelenting, he was seldom passed and against whom few dared to take a shot. He did show some outside shooting ability, though it was uneven, and because he played low against taller players for the most part, he was susceptible to fouls. But Meno and the others picked up the slack when he went to the bench. He even inspired confidence there just in the way he sat and watched.

The whole team was disciplined, well-conditioned, and quick enough. They played hard the entire game and ran with faster teams. They executed well in all the details, forcing many turnovers while making few themselves. Their offense was an orchestration of movement that controlled the tempo and worked it to their advantage, spreading out the defense, working open lanes, setting a maze of screens to find a clearing for Curry. Yet when they found an opportunity, they could push the tempo and get off a quick shot. They were seldom caught off guard, were always back on defense, and once there pressured inside and out, often being in the right spot to stop a drive or make a steal—and make a quick transition back to offense, even score on fast breaks, a threat no one thought they had. And they were a scrappy team. Everyone fought for rebounds and hit the floor for loose balls.

Those reasons, however, are not enough. I haven’t touched what I know McKillop would say lies at the heart of the reasons.

But I find myself standing still…

.

Davidson came out first for warm-ups, greeted with an ovation from Christopher and me and the handful more of us scattered in the stands, but largely silence from the rest, a few boos. McKeon was already packed, with more filing in to find what space they could and everyone readjusting and squirming in the communal squeeze. Below us the student section, most there wearing “Moraga Madness” T-shirts made for the occasion, printed with the numbers of Mills and Curry, 13 and 30. Bright red, they obliterated our red Davidson shirts. We really wanted our team to see us.

As I watched them perform the layup drill, casually, with gradual loosening, I realized why I most wanted to come. TV, with its close-ups and replays and selected angles, gives an exaggerated view. I wanted to see them live, and live they looked smaller and fallible, yet not smaller than life or unskilled, but, in fact, human.

Nor does TV show warm-ups, the ritual that provides a team’s first interchange with the crowd, a testing of the medium through which their shots will fly. Here there was only a low murmur, a mood that felt heavy with reserve and maybe some resentment, and the Davidson players looked contained, practicing within themselves, preparing for what their later efforts might not return. Curry, his warm-up pants loose, tripped and fell, and my heart jumped, but he bounced back up and made an antic did-that-just-happen gesture, which got no response. A sprained Curry ankle was worth national headlines, and he was, in fact, recovering from one suffered a few weeks before. It was not a friendly crowd.

Then the Saint Mary’s players came out in a slow, deliberate strut, their heads high, their faces broadcasting a show of confidence to the stands, and the reserve we saw on campus earlier unleashed itself into loud approval. As they performed their layups, each was an assertion of certainty, reassuring the crowd.

Then there was open shooting, a shift to lower percentages, while we in the stands calculated odds, and the noise subsided as players on both sides hit and missed.

Also present, or about to be, the nation, as ESPN2 would broadcast the game, a third member of the conversation. Not present, and still part of the discussion, the audience we might have had had both teams been selected for the NCAA tournament. And present, and still part of the discussion, the probable futures of Mills and Curry. I later heard Chris Mullin, general manager of the Golden State Warriors, was there, along with ten NBA scouts.

The noise ebbed and swelled the next half hour, circulating around the stands and returning to itself in confused murmur as latecomers slipped in where they could, the noise, the crowd mood asserting then debating itself, arguments of what we invested in the players, in the game, in our humanity, what any of these meant, of how we stood before a national eye, before the eye that had overlooked us, the mood not altogether wholesome, mixed with slights and doubts and resentments, the noise lowering as Davidson was announced, though the boos were louder, especially for Curry, then surging for Saint Mary’s, spiking with Patrick Mills, then lowering and circulating in the packed stands, milling there in compaction, the mood suppressed, up until tip-off, when it released itself and everyone stood and roared—

[B]ut to see two men smashed to the ground, smeared with gore, stunned, senseless, the breath beaten out of their bodies, and then, before you recover from the shock, to see them rise up with new strength and courage, stand steady to inflict or receive mortal offence, and rush upon each other “like two clouds over the Caspian”—this is the most astonishing thing of all.—This is the high and heroic state of man!

Hazlitt, from “The Fight.” The allusion is from Paradise Lost.

.

Michael Kruse, a Davidson grad now a reporter, writes that McKillop recruits players as much for their character as their talents. He looks to see how well they assert themselves, how much they scramble. Whether they throw themselves into their play, how much they can put their egos aside and not be self-absorbed, how quickly they can put failure behind them and play on. What impressed him about Curry was that he showed the same face when he made a shot as when he missed. Lovedale caught his attention in Manchester by the care he put into sweeping a court, getting it ready for the boys he was to coach in a clinic.

Here I take notes for what I can pass on to my son, what I might yet figure out for myself.

McKillop, who grew up in working-class Queens, the son of a city cop, originally planned to make a quick run through Davidson and the Southern Conference to launch a career in college basketball. He was driven to the point of being overbearing and pushed his teams too hard. They did not respond well, and his first teams suffered embarrassing losses. After a few years he realized he had to change his priorities, deciding he first had to restore values in his coaching and for the team. Teamwork, of course, and Trust Care Commitment was the team’s motto, written on team T-shirts and on a sign in the locker room, its initials now tattooed on Curry’s wrist

This is where I hesitate. They are things that I tell my son but cannot raise with conviction.

David Higgins, in his essay on “The Fight,” notes that Hazlitt was promoting the traditional values of English pluck and self-determination, his purpose being to adopt those to bolster his politics and his art. But prize fighting was also followed closely by the Tories, who watched it to see asserted the same values. Hazlitt ran the risk of losing his finer point and leaving intact the same traditions that sent working-class England to its slaughter in the trenches of World War I. Nor does Hazlitt inspect the values he promotes, even on his own terms.

Traditional values can be a mask for power, leading to conformity and suppression—I have been trained to think that way as well. I have not been suppressed, but I have always mistrusted teamwork. From what I’ve seen, it can lead at best to compromise, lowest common denominator decisions of what a group can all accept. Or it has been promoted blindly by those in charge, without consideration of how members fit or what they might contribute, where their only option is to do as they are told. Or it is praised abstractly, as some airy goal in itself, without much thought as to what it is supposed to accomplish. What I’ve seen in my experience I have also seen elsewhere, on a larger scale. Then again, I don’t think I’ve really seen true teamwork.

Hazlitt’s rendering of the fight may startle us, if it doesn’t make us laugh, but I realize much of my life I have found such a stance attractive, and in many ways it has guided me. English resolve is not far removed our own rugged individualism, attractive as well. We are supposed to slug it out on our own. I have always been suspicious of the values held above me, whose main effect can only be to hold me back. Trust can lead to blindness and submission, care to softness, and both to some sentimental notion of a self without edge or force. Seeing the position in Hazlitt’s stark expression, however, makes me wonder how well it has served me. Toughness and self-reliance can lead to endless conflict, to loneliness, to loss of purpose. On a societal level, they can lead to mass dissolution—or periodic outpourings of massive and unquestioned violence. Self-reliance can cover communal urges, deep and disturbed. It might do us all good to think how well we have been served by keeping to ourselves.

McKillop is also religious and often cites scripture, from which he draws lessons he applies to his coaching. Lovedale and Curry talk about their faith as well, its influence on their play. Last year Curry inked on his shoes the much publicized “I can do all things” from Philippians 4:13.

And here I come to a stop. I have made religion an option for Christopher but haven’t followed up.

My skepticism about faith, as about values, as about nearly everything, however well-founded, has left me at loose ends. Though I know there is not much to be found at either end, I have no firm sense of whether I am good or bad in any sense. Nor do I know what spirit moves me, or if there is one. I have to wonder about what kind of model I present for my son.

While not necessarily a reflection of either, the fusion of church and state, in England’s past as here in recent years, is troubling in the ease with which it has occurred. But room has to be made for faith as well as doubt. While I grew up in a Presbyterian church, I never attended the one at Davidson and set religion aside long ago. Last year, however—I should make it a fourth event for this essay—I stumbled across a piece by Marilynne Robinson in The Best American Essays 2007 that discussed, of all things, the theology of John Calvin. She notes the irony that fundamentalists today have somehow managed to join the mission of Christianity with that of capitalism while at the same time overlook Christ’s love of humanity, His concerns for our well being, all of us, and our salvation. Such a horrible contradiction, and really a damning indictment—how has that irony survived?

But this is the thought that struck me most and made me rethink Presbyterianism in particular and religion in general: “Calvinism encourages a robust sense of human fallibility, in particular forbidding the idea that human beings can set any limits to God’s grace.” Because of our fallibility and because of this distance that cannot be closed, none of us—and no institution, religious or other—can claim a mandate from God we can pass on to others. Our history is filled with too many examples where our institutions have gone horribly astray. But our existence is based on His love of us, all of us, a condition just as unassailable. It is this love that gives us hope and encourages us to keep trying, keep finding ways to better our lives and the lives of those around us, and keep testing and refining our institutions. It is when this love is forgotten that heads begin to roll. We have every reason to doubt what we say and do, but our salvation, here on earth and later, depends on constant love and application of our faith. Still we doubt, but doubt encourages tolerance, allowing us to accept each other and “live together in peace and mutual respect.” Uncertainty is not a detraction from faith but one of its terms.

In many ways such an understanding was implicit at Davidson, and I realize now the influence of my earlier years in church. I still haven’t sorted out my religious views. I am certain of this much, however, that I have profound—call it religious—respect for all that I do not understand, all that has not yet been figured out, all that never will be figured out or understood. I also stand in awe of all the ways we have violated our best intentions—start with a body count of the horrors of the last century, then add the numbers for this one. But there has to be something about me, about all of us, that is vital, that is valid, that must be preserved, and something outside ourselves just as vital, and some way to talk about both and factor them into our lives. Call it faith in faith. These belong to the domain of religion, and we have centuries—millennia—of discussions to review. I will always remain skeptical, but it is because I cannot answer fundamental questions of doctrine that I do, in fact, have faith. Doctrine will always lead to conflicts and debates, many of them useful, but answering such questions still leaves too many questions unanswered. Uncertainty is sustaining and keeps possibilities alive, the discussion open.

Those who are religious might complain utter compromise, but I see a lot of common ground.

As for those who are not religious, I can only ask them to look at the images of humanity and the world they offer and consider how well those images fit us, they serve us, what they ask us to look at, what they give us to strive for—then see how much they miss the mark.

Presbyterians also believe in salvation through good deeds: what we believe should be put in action. McKillop, though Catholic not Presbyterian, doesn’t just say the words, he practices them. He made the change not for the team record or his career, but for the players themselves. He realized he had to restore their belief in themselves and in their desire and motivation to play, to be themselves and reach their potential, all rewarding in themselves. Winning was a by-product. He still drove them hard, but now they responded. As for religion, I have never heard an instance of his praying for victory or playing for God to fulfill His purpose. “Walk humbly with your God” McKillop tells us, citing Micah 6:8. Rather, voice is given to what coach and players believe in, giving it a chance to flourish and make them whole. Curry’s “I can do all things” is not egotistical at all but rather a testimony to his faith. The full passage is “I can do all things through Him who strengthens me.” In an interview with ESPN he explains, allowing other interpretations: “Don’t play for anybody other than your family, or God, or whatever you believe in. It’s easy to get caught up in playing for the crowd, trying to play a game you’re not capable of.”

Faith, values, and the voices of the heart perhaps cannot be defined, and they suffer most when we nail them down or tie them to a cause. But we can express them and look where their exercise leaves us. I have the NCAA tournament games on DVDs and still watch them. The 17 point deficit against Georgetown should have demoralized Davidson, but it didn’t. The players never stopped running or looking for opportunities. In none of the four games did any of them look like they thought they were going to lose. And they should have been exhausted after pulling even with Georgetown. Instead, they looked refreshed.

David Foster Wallace was editor of the 2007 anthology, an excellent collection, with essays he selected because of our current political and cultural crisis. We do have public critics, but they are not heard.

His death last year makes a fifth event.

.

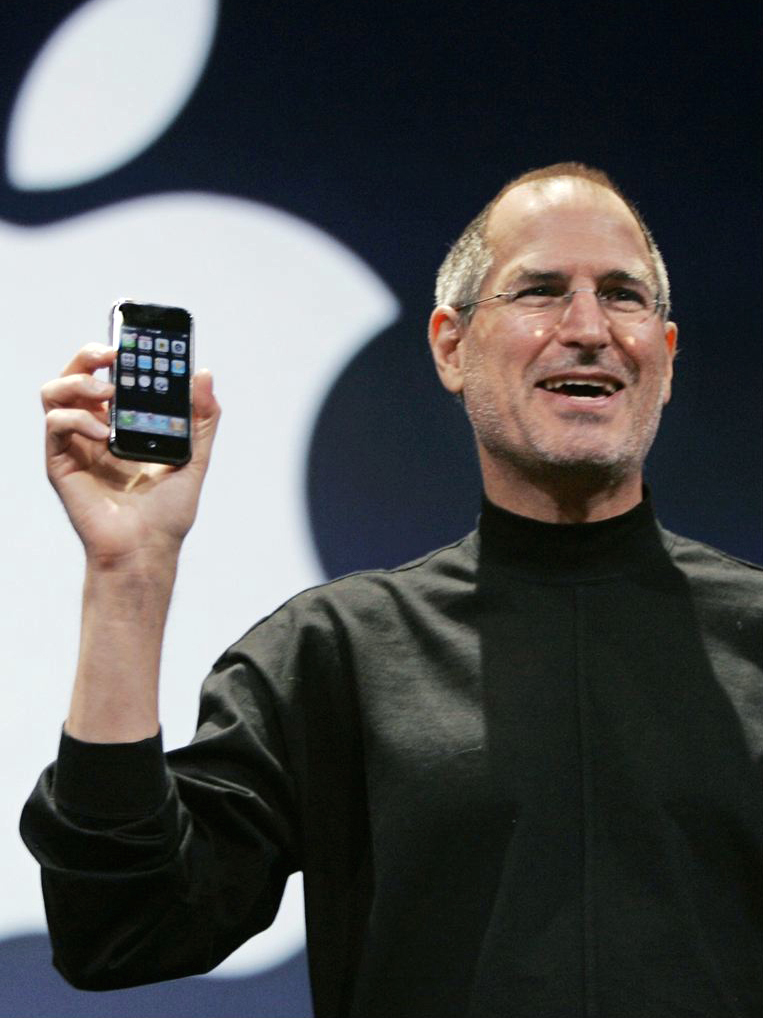

But teamwork, discipline, and faith are still not enough. Of course there is Stephen Curry.

To write about Curry is to risk falling into the temptation of superlatives while depriving oneself of the tools of ironic cuts. But to watch him play is to have belief stretched and received notions, our perceptions of what we think is possible and what is not, thrown out the window.

In the four NCAA tournament games last year he made 13 steals, 13 rebounds, 14 assists against only 5 turnovers—and scored 128 points. In the Gonzaga game he was 8 for 10 from the three-point line, though his percentage was low against Georgetown and Kansas. Still, he kept shooting and eventually the ball started falling in. He was a major reason the team believed they could come back. Against Georgetown he scored 25 points in the second half, 30 against Gonzaga. What makes his numbers even more impressive is that he was able to produce against very good defensive teams, and since he was the major scorer they were able to key in on him, rotating defenders and working double—and sometimes triple—teams. All of this he accomplished when no one thought he could play at the college level in the first place. No major teams wanted the slender six-footer out of high school because they thought he was too small to contend in a game that depends more than ever on power and physical intimidation. Virginia Tech offered him a walk-on slot, while the rest of the ACC overlooked him entirely.

He can do all things. On offense he only needs the slightest opening and gets his shot off fast, his form a synthesis of concentration and split-second decision, of balance and gymnastics. On good nights, and he’s had plenty, he has extraordinary range and accuracy. This season he hit a 75-footer at the halftime buzzer against Chattanooga, and the amazing thing is that I don’t think anyone was surprised. He has conditioned us not to expect him to make shots, but to hit the hoop dead center, giving us that gentle yet peremptory caress of the swish that glides into and seizes our hearts. He can also shake a defender and pull up in the key, or find a narrow opening in the crowd under the basket and slip through for a layup, in either case switching to his left hand if he needs to. This is what makes him tough to defend, that he keeps his opponents guessing, and he knows how to work their uncertainty with feints and moves they cannot predict. Late against Georgetown, coming off a Lovedale screen, he dribbled behind his back, stalling his defender, then popped a three that put Davidson up for good.

He doesn’t just shoot, but is active full court and knows how to read both ends. On offense he is in constant motion, running through screens, finding open lanes. He also dribbles well and can break a press, then, still on the run out of the corner of his eye catch an open player and flick the ball for a quick two. On defense he puts the same energy into guarding his man and with quick hands can force a turnover or make a steal. Or he can switch off at the right moment as a play develops and take on other players, and he is not intimidated by any. He took a charge against Georgetown’s 7-4 Hibbert. Against Wisconsin, he leapt to block 6-11 Stiemsma driving for a dunk. Or he finds the right spot to cut off a pass, or, seeing a turnover, immediately races back down the court for a fast break. In fact he seems to have solved the mystery of perpetual motion. Though he plays nearly the entire game, he doesn’t slow down but seems to become more energized the more he plays.

To be sure, he led scoring this year because he was allowed to take so many shots. Other players—Jodie Meeks, for example—might well have scored as many if put on a similar team and cast in the same role. Nor does Curry make all his shots and he has his off days. This year his shooting percentage fell somewhere short of phenomenal. I doubt, however, any other player could have inspired a team as much. It is only my speculation, but I don’t think Curry is so much a team leader who commands respect so he can call the shots and direct play. Rather he brings a spirit to the court that others see, that taps into their own spirits and encourages them to lead themselves. Or maybe he encourages them to stop thinking about roles and chains of command, and instead look to themselves and what they can do. Teams should be built from the bottom up, not top down.

For me, the attraction is not his production but who he is and the way he plays. He shoots because that is his job, but he will do anything to help the team. He sets screens for others, and this season when they played Loyola Maryland against an exaggerated double-team he took his defenders to a corner where he watched his teammates win a lopsided victory, taking only three shots and scoring no points. He never gloats or gets down on himself or loses his composure. He just plays, and does so with a playfulness that is nonetheless serious in its results, showing a selfless joy in which I hope he does not lose himself, and I doubt he does. Watching his effortless long-range shot is like seeing the flow of some easeful, natural force that rises from the floor through his extended legs and arms and up into the rainbow of his shot, and when he shoots we all collect our breath so we can release our cheers as the ball does what it does so often, make its soft descent into the net, when our cheers touch ecstasy. To watch him is to believe that grace is a force in nature.

It goes without saying that Curry is talented and that he has spent countless hours with practice and conditioning. But also he is inspired in every sense of the word, and I won’t argue against what he claims to be his source of inspiration. His play is artful, and what he reveals is imagination at work in his ability to picture the scheme of play and see options others miss, finding a variety of solutions to the game’s shifting, complex demands. Or he might dribble behind his back and split two defenders and try to make something out of nothing. He creates what we haven’t seen before and didn’t know could exist, beautiful in what it might imply. To watch him is to wonder if all things might not be possible. But we also see a play of spirit beautiful in itself, and, for a moment, can put implications aside.

I overdo it. Then again I don’t think I’ve gone far enough because watching Curry and the team last season had this effect on me, that I started looking for openings myself in my life and in my work and thinking of solutions where before I only saw impasse. The team helped me to look up. I’ve read that he inspired the entire Davidson campus as well, and it’s hard not to believe that all who watched him didn’t feel their spirits lift.

I especially wanted Christopher to know Curry because I am always looking for role models. Hey, look at this guy—I showed him some YouTube highlights a year and a half ago, when I first heard about Curry—and Christopher took to him at once. Both have almost the same height and weight, and the same ethnicity—Christopher is adopted. I wanted him to see Curry’s character and have a companion in his spirit. He is growing up in a world that gives him plenty of freedoms, thrilling and superficial, yet also one with limited options and rigid requirements of how to make it there. He has gone to very good, but very demanding and competitive schools, where he hasn’t yet hit his stride, taking required courses that do not always speak to him, learning under the mechanical strictures of point counting, the pressure of the need for high SAT scores and GPA’s to get into college. It is a system that does not question itself and often contradicts. Life will not be much different when he gets out of school. I want him to keep looking for options and see what he can figure out for himself, to never stop trying and always keep his head up.

Christopher also plays basketball, thus his special interest in Curry. High school basketball is much more competitive than I remember it at my age. So many more show up for tryouts, and it is hard to establish a place once on a team and find room to develop. Play can become bogged down as the boys assert themselves yet fight their doubts, often ending up in their avoiding outside shots and clogging up the paint. Curry didn’t first put the thought in his head, but he certainly reinforced a desire. Christopher has always wanted to bomb away, and his coach turned him loose. His shooting was off during the season this year, but during summer league he went through a stretch where he hit from the perimeter with startling percentage—4 for 8, 5 for 7, and in one game, where he only played twenty minutes, 7 for 11. He also played for a local AAU team last summer and bombed away there as well. At first he got dirty looks from the other players—until he started making his shots and, with his points, keeping them in the game. As with Davidson outside shooting can do much to reverse the odds and open up the dynamics of play.

Most, I want Christopher to assert himself, but also, like Curry, be himself and enjoy what he does. I hope he never loses his spirit. My favorite picture of him is of his making a steal and—he is fast—tearing down the court, breaking free of the others chasing him, and laying up.

There was a sublime five minutes of basketball in Davidson’s game against Wisconsin that showed what Curry and his team could do. Wisconsin, the heavy favorite, was much taller, though less assertive, and the game was close up until the last fourteen minutes, when expectation told us that Wisconsin would finally assert its size and pull away. Instead Davidson shut the Wisconsin offense down, holding them to a handful of shots, while they themselves scored at will. First Richards, Davidson ahead by 3, brings the ball up, starts to drive, but then makes a quick pass to Curry who has just slipped a screen, who quickly shoots from the arc and swishes. Up 6. Wisconsin on its possession gets the ball to Krabbenhoft who drives, but Curry comes from behind and knocks the ball loose and Richards picks it up and starts back and Curry is already racing down the side ahead of him and Richards passes to the corner, where Curry loads and Krabbenhoft, rushing desperately back, makes a running leap to stop his shot, and Curry waits for him to fly by, then reloads and nails another. Up 9. Davidson forces a tie-up on Wisconsin’s next possession, then a turnover on the inbound pass. Davidson ball, Richards takes the shot this time, several feet behind the arc, and swishes. Up 12. Then Meno steals in the backcourt and Davidson, with the ball, keeps getting offensive boards and takes several shots, Richards finally banking in a three, though it doesn’t count as the shot clock has expired. Then Davidson rebounds on defense and on offense the ball goes back to Curry who dribbles off his defender and swishes yet another three. Up 15. Wisconsin only manages a free throw in their next two possessions, then comes the shot that brought the house down. Richards, seeing Curry cut for the basket, shoots a pass to him off the dribble with his left hand and Curry drives from the left side to the right, where he spins 180 and, behind the board, his back to the stands, fronted by Stiemsma, who fouls him, underhands a layup, then makes the free throw. Up 17. A few possessions later, with Curry on the bench taking a breather, Lovedale, playing out, makes a quick cut and already the ball comes from Richards into the opening both know is there, though they scarcely looked, and Lovedale drives for the dunk, keeping the lead at 17. Wisconsin never closed the gap.

I suppose it would be attractive to offer some kind of lesson or draw a moral from their performance last year. I don’t want to do anything of the sort. Sports are gloriously pointless; keeping score only highlights that point. Our expectations in the NCAA tournament are excessive—March really is a madness—but we need some container for our excitement so we can turn it loose. We don’t have to justify sports any more than we have to explain our existence. Rather they tell us that our lives at any given moment matter, giving us a meaning that cannot be reduced to some abstraction or taken out of time, offering us a chance to assert ourselves and express our better spirits and enjoy our time together. Sports provide overwhelming evidence that we are, in fact, alive.

I would be curious, however, to see what kind of world we might create if we were allowed to exercise our faith in ourselves, in something higher, and give our hearts and minds full range.

.

I will spend even less time on the Saint Mary’s game than Hazlitt did on his fight. The context made it exciting and I finally got to see the team and had a chance to stand and give my affection full voice, but I realize now the game itself wasn’t that important to me. I’m not sure what victory might have meant. Davidson would have had a long haul to make it to the finals of the NIT against several other competitive teams, all out to prove themselves, and I’m not sure how satisfying winning at Madison Square Garden would have been in a tournament that isn’t taken seriously, at a time when the nation’s attention is on the NCAA. Their season had to end somewhere.

The NIT, of course, is not a big deal.

Also, they lost.

Richards graduated last year, so Curry moved to point guard, where he showed much talent, ranking high in assists. But the move put a greater load on him as now he had to bring the ball up and run the offense. It was harder for him to shoot because instead of running around screens for openings he had to work much harder to get clear looks. Defenders could key in on him when he had the ball, and he couldn’t very well pass to himself.

But in the first half of the game, we saw how the offense could work. With so much attention on Curry, other players were open and Curry fed them, though they missed several mid-range shots. Still, Davidson got out to an early lead, but then stumbled and Saint Mary’s made a run. Davidson pulled back, and the half remained tight and tense, Davidson only down three at its close. At some point Christopher and I stopped sitting and just stood, following the student section’s lead. Neither of us stopped shouting either, yet we scarcely put a dent in the crowd’s mood, loud though still not sure of itself, and often raucous. They cheered when Curry missed a shot and were silent only once, early in the half, when Curry slipped in a quick, long-range three, a reminder of what he could do, of what could keep coming.

At halftime I went outside to a roped-in area to smoke. There, much mulling over and unresolved tension, and disapproval of my shirt. Inside, the Saint Mary’s dance team, some twenty of them, entertained those who stayed.

Curry opened the second half with another three, tying the score, but Mills replied with a quick layup. The game remained close for the next ten minutes, Saint Mary’s gaining the lead, but even with six minutes to go Davidson was in range. Yet Saint Mary’s pulled away, the crowd mood finding the clarifying voice of victory, and they finally won by 12. Curry did score 26 points, but it was Patrick Mills’ show. While he didn’t shoot well from the outside, he still could drive and scored 23 himself. He really ran the offense well—10 assists—and the whole team responded, playing together, their play inspired. They also covered Curry well. Forward Diamon Simpson and center Omar Samhan, big men with skills, had fine games, and Mills was able to find them. When the game was over, Mills invited the crowd to the court, where they flooded.

Mills would make a good story—someone should write that essay. Leon Powe, at Berkeley, my other alma mater—Christopher and I saw him play a few years ago—would make another. There are plenty of good stories in college basketball, in all sports, all of them different, and all of these essays should be written.

The Davidson resurgence of last year didn’t happen. My view is the team was a few pieces short. We couldn’t match up with Saint Mary’s size—Miami agreed with me. Sander and Meno also graduated last year, putting most of the inside load on Lovedale, who was well guarded and had to watch his fouls. Without an inside game, more pressure was put on the perimeter, on Curry. Maybe the team relied too much on Curry, maybe he had too much to do—he also got 9 rebounds. But Davidson didn’t execute well—17 turnovers, 6 by Curry. The team was uncertain of themselves. They also looked tired, even Curry. It had been a long, emotional season, trying to play to last year’s expectations and appearing before packed houses. They were in the national spotlight for an entire season and fell under the scrutiny of a critical press that debated the team’s worth all year. McKillop himself acknowledged that pressure and its effects.

I know I am supposed to make some philosophical statement about loss and its meaning, perhaps concede the necessity of a return to reality, but I have no interest whatsoever doing so here and don’t see any point. They just lost. Nothing can diminish what they accomplished, or what others, what any of us, given the right circumstances, might yet do ourselves. And reality is a subjective study. We have to be careful to see how it is defined, by whom, and why.

Still, the loss upset me. I had invested a great deal into the team, which I now would have to recover, on my own. I was tired myself—it was a long, emotional day.

.

The crawl out of the parking lot, the late drive on the rough freeway, the winding road, dark hills. Not much traffic, but it was a strain to see the lines, worn and faded…

.

Thoughts on returning home, the returning thoughts…

.

No comment from Christopher or any idea of what he thought because he soon fell asleep and slept the whole way. He was exhausted.

.

How does one talk to one’s son?

.

Tom Hickman, “The Gas-man,” did get up in the twelfth and fought six more rounds, though still took a beating. But he couldn’t come to his senses in time after the eighteenth, and on December 11, 1821, Bill Neate was declared the winner.

— Gary Garvin

.

Sources, in order of appearance:

Terry Eagleton, “The Critic as Partisan,” Harper’s Magazine, April 2009, pp. 77-82. He reviews Duncan Wu’s recent biography, William Hazlitt: The First Modern Man.

David Higgins, “Englishness, Effeminacy, and the New Monthly Magazine: Hazlitt’s ‘The Fight’ in Context,” Romanticism, 10.2 (2004), pp. 170-90.

All comments on McKillop’s coaching from Michael Kruse, Taking the Shot (Butler Books, 2008).

Marilynne Robinson, “Onward, Christian Liberals,” The Best American Essays 2007, ed. David Foster Wallace (Houghton Mifflin, 2007).

“I can do all things,” from Curry interview, Kyle Whelliston, “Curry shrugs off the glory in Davidson’s Elite run,” ESPN.com, March 29, 2008.

McKillop comment that they were tired from Stan Olson, “Wildcats play free of pressure,” Charlotte Observer, April 1, 2009.

.

.

Gary Garvin lives in San Jose, California, where he writes and teaches English. He has written two novels, and his essays and short stories have appeared in Numéro Cinq, the minnesota review, New Novel Review, Confrontation, The New Review, The Santa Clara Review, The South Carolina Review, The Berkeley Graduate, and The Crescent Review. He is currently at work on a collection of essays and another novel.

.

.