When I read Karen Solie, I’m reminded of my first encounters with Berryman’s Dream Songs, Lowell’s Life Studies, or Vallejo’s posthumously published poetry. The books seemed unrelentingly astonishing, had a skewed but insistent sense of moral gravitas, and demanded a response that was as physical as it was intellectual. —David Wojahn

The Road in is Not the Same as The Road Out

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015, 104 pp.

Hardcover, $25.00

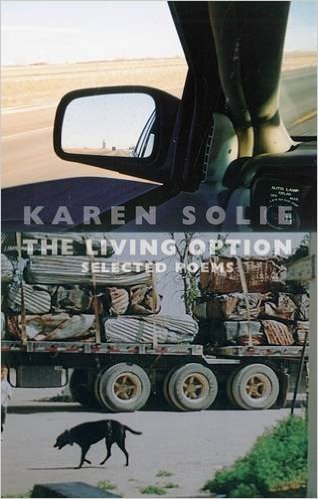

The Living Option: Selected Poems

Bloodaxe Books, 2014, 160 pp.

Paperback, $9.95

.

In 2014, upon the British publication of The Living Option, a volume of Karen Solie’s new and selected poems, the poet-critic Michael Hofmann, writing in The London Review of Books, lauded the collection in a manner that surely surpasses any poet’s most delicious fantasies about what constitutes a positive review. Hofmann heaped on the tributes so thickly that a reader unfamiliar with Solie’s work could easily have been lead to wonder if Hofmann had written the piece under the influence of some sort prescription mood enhancer so appealing that you’d love to get your hands on some of it—though perhaps not for the sake of writing about a poetry collection. By the end of the second paragraph of the review Solie was seen by Hofmann as the peer not only of well-regarded contemporary poets such as Frederick Seidel, Les Murray, and Lawrence Joseph, but also Big Shots from the pantheon—Brecht, Brodksy, Whitman, and Stevens got namechecked as well. That Hofmann would lavish such praise on a writer who had published only three collections before her Selected, all from small presses in her native Canada—she was born in on a farm near Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, in 1966, and now resides in Toronto—made the review all the more remarkable. Solie’s nationality also offered Hofmann an opportunity to tartly disparage the chauvinism of the UK and US literary establishments, who tend to regard other Anglophone literatures as what he witheringly characterized as “apocrypha or appendix, the province of specialists or pity.” Reviews of such unabashed ardor are exceedingly rare in the world of poetry, particularly when they arise from the subculture of Pavlovian snarkiness that passes for poetry reviewing in the UK. And when such reviews do appear, their claims tend to be hyperbolic or just plain wrong. But about Solie Hofmann was for the most part spot on. I’ll refrain from the Whitman, Brecht, and Stevens comparisons here, but I have no hesitation in saying that Solie is one of the most exciting poets at work today. And with the US publication of The Road in is Not the Same as the Road Out, a volume of Solie’s recent work, readers in the States can see something of the breadth of Solie’s accomplishment.

I hasten to add that something, for neither The Road in…. nor the perplexingly skimpy selection of Solie’s poetry included in The Living Option allows a reader to accurately assess the niceties of Solie’s development, nor to appreciate the remarkable consistency of the quality of her work. The Solie of The Road in… is a garrulous and impishly meditative poet. The poems start with oddball but tangible subject matter (with titles such as “Roof Repair and Squirrel Control,” and “A Good Hotel in Rotterdam”), but then immediately grow loopily digressive (or darkly sardonic) and tend to wander about engagingly (or scathingly) for several pages. Solie’s earlier work, however, is somewhat different from this later style: many of the poems are short, acerbic lyrics—and in subject matter they are deeply reflective of the flatness, vastness and desolation of Canada’s prairie provinces. The work is regional in the best, Wordsworthian, sense, always keen to give itself “a local habitation and a name.” In Solie’s case, this fidelity to the local means a preponderance of poems that take place during stultifyingly long car rides, in strip malls, in barely half-star roadside motels, in dive bars, or on those scary puddle-jumper jet flights from one unremarkable city to another, where determining the right mixture of Xanax and vial-sized booze bottles becomes a kind of survival skill. Some of these poems appear in The Living Option, but not enough of them. One really has to seek out her early Canadian collections, Short Haul Engine (2001), Modern and Normal (2005) and 2009’s magisterial Pigeon to get a complete picture of Solie’s accomplishment.[1]

The only reasonably priced copy of Short Haul Engine I could find on Amazon when I was composing this essay has a very large stamp on its inner cover that reads, “WITHDRAWN FROM THE COLLECTION / WINDSOR PUBLIC LIBRARY BUDIMIR BRANCH.” And in my library copy of Modern and Normal, a reader has used a pink highlighter pen to single out poems that she especially likes, along with handwritten notes in the margins, set down with the careful but shaky penmanship of someone more skilled with keyboards than with writing implements. Still, Ms. Highlighter Pen is some places a fairly astute critic. Here are the margin notes which accompany a characteristic early Solie poem, entitled “Nice”:

—disconnected

—mundane

—fleeting thoughts

—calm, shrug

And here is the poem itself, complete with its epigraph from Diane Arbus:

Nice

“I think I’m kind of two-faced. I’m very ingratiating. It

really annoys me. I’m just sort of a little too nice. Everything

is Oooo” –Diane Arbus

Still dark, but just. The alarm

kicks on. A voice like a nice hairdo

squeaks People get ready

for another nice one, Low 20s,

soft breeze, ridge of high pressure

settling nicely. Songbirds swallowing, ruffling,

starting in. Does anyone curse

the winter wren, calling in Christ’s name

for one bloody minute of silence?

Of course not. They sound nice.

I pull away and he asks why I can’t

be nicer to him. Well,

I have work, I say, and wouldn’t it be nice

if someone made some money today?

Very nice, he quavers, rolling

his face to the wall. A nice face.

A nice wall. We agreed on the green

down to hue and shade right away.

That was a very nice day.

Quite an acrid little meditation, this, and not an unfamiliar one if you’re conversant with what we’ve now come to reductively call post-modern style. And Ms. Pink Highlighter Pen has unwittingly listed many of the rudiments of that style, with its discontinuity, its irony, its offhanded critiques of the vapid platitudes of media and consumerist culture (“…get ready/ for another nice one…:” “We agreed on the green/down to hue and shade right away”); its associative slipperiness. And yet, although “Nice” shows us how skillfully Solie can walk the po-mo walk, she shows just as strong an allegiance to more traditional poetic devices. There’s the Hopkinsian linguistic tour de force of “Songbirds swallowing, ruffling,/starting in,” and the Eliotic diction of “Does anyone curse the winter wren?” as well as the loose tetrameter of the poem’s key lines. Furthermore, “Nice” is quite cunningly structured, seeming to free associate in its opening, before ending with an old-fangled narrative description of domestic discord and regret. Although Solie has almost bludgeoned us with her examples of how the word “nice” has been debased in our vernacular, the poem’s final line asks to be read with pathos rather than irony. This realignment does not come without warning. The ambivalence and self-criticism of the Arbus quote has prepared us for it. Like Philip Larkin at his best, Solie here—and in many other poems as well—begins with dyspepsia, but slowly and methodically turns her bile into something bracing. The poem closes not with a calm shrug (or “calm, shrug”), but with a gesture of guarded epiphany.

Solie is, above all, a voice-driven poet. Of course, so are countless numbers of her peers. But she differs from her peers in no small measure because she has found that voice through a hybridization of a very unlikely pairing of masters. She has obviously learned much from John Ashbery, and has cited him as an influence. You see this in her abrupt shifts of tone and diction, in her use of found poetry and goofy titles (among my favorites are “Your Premiums Will Never Increase,” “Self-Portrait in a Series of Professional Evaluations,” and “When Asked Why He Was Talking To Himself, Pryrrho Replied He Was Practicing to be a Nice Fellow”); in the ways in which her whimsy often gives way to dread, and in her delight in mixing high and low culture references. This latter quality is especially appealing. On the one hand she offers us poems with titles such as “Meeting Walter Benjamin” and “Sleeping with Wittgenstein,” while on other she relentlessly samples lyrics and song titles from classic and post-punk rock, sometimes with attribution, but mostly not. There are nods to the Band, John Lee Hooker, X, REM, Nick Cave, Paul Kelly, and the Jesus and Mary Chain, among others. But Solie also understands that the effete cosmopolitanism of Ashbery doesn’t in the long run speak to her milieu. A poem such as “Medicine Hat Calgary One Way” takes places about as far from New York and the New York School as one can get, both geographically and aesthetically—the speaker is on a bus, passing “Strip malls and big box stores whose/ faces regard with solemn appreciation/the shifting congress of late model vehicles/ who attend them” and a “downtown deserted as the coda/ to a biological disaster.”

You need an entirely different model to describe this sort of landscape and the particular melancholy which attends it. And Solie has found that model in another poet she has cited in an interview as an abiding influence, and evokes in an epigraph to a section of Short Haul Engine. Regrettably, he is a figure who has fallen out of fashion—Richard Hugo, known today, if he is known at all, as the author of a classic creative writing textbook, The Triggering Town. But Hugo is among the most significant poets to have emerged from the North American West. He is also in almost every conceivable way the opposite of Ashbery: he is baldly confessional where Ashbery is self-concealing; he is largely narrative in his approach where Ashbery is militantly non-linear. And his allegiance to the Romantic tradition is a far cry from Ashbery’s Duchampian nihilism. Hugo doggedly adheres to the Wordsworthian notion that nature is a metaphor for the self—and vice versa. But Hugo is also a wounded Romantic: for Hugo, whatever natural grandeur the West once had has been despoiled. It is now a quietly dystopian realm of half-deserted mining towns, crummy roadside bars, long unvarying drives on the Interstates, and unhappy and impoverished childhoods that morph into similarly unhappy (and usually alcoholic) adulthoods. And it often seems as though Hugo is constitutionally (rather than merely aesthetically) unable to distinguish self from landscape, identity from setting. In “Degrees of Gray in Philipsburg,” his best-known poem, after offering a brutal tour of a nearly deserted mining town, Hugo makes the connection unequivocally clear: “Isn’t this your life?…../ Isn’t this defeat/ so accurate the church bell simply seems/ a pure announcement: ring and no one comes?” What saves Hugo’s work from too frequently succumbing to the maudlin—and what saves Solie’s poetry from this as well—is a kind of laconic humor that leavens even his most disconsolate efforts, offhanded observations along the lines of “George played rotten trombone/ Easters when they flew the flag.” I think it’s safe to say that Hugo’s West is strikingly similar to Solie’s West, and her move to Toronto has not significantly diminished her preoccupation with her prairie province upbringing. And her particular command of tone, of a biting wit that barely conceals a deeper distress, derives in no small part from Hugo as well. At the start of a grimly ironic Solie poem entitled “Possibility,” she and Hugo might as well be traveling in the same rental car, and checking into the same Day’s Inn:

A rented late-model car, Strewn gear. Clothes,

books, liquor, one good knife for slicing

limes. Motel the orange of an old rind. Bud green

and remaindered blue for trim. Some schemes

shouldn’t work, but do. A square room

with balcony two floors above the strip. Real

keys. A man sleeping on the bed,

or pretending to. It will be alright. It’s not

too late. We left on the sly and nothing bad

happened….

I hasten to add that Solie has been influenced by a number of other figures, though none as profoundly as Ashbery and Hugo. You can detect a debt to Symborska in her use of tone, and one to Transtromer in her approach to imagery. And—although I may be presumptive in thinking she reads, or has needed to read, a great many poets residing south of the 49th Parallel—you can also discern a smidgen of Dean Young and Tony Hoagland in her associative see-sawing, although she never succumbs to Hoagland’s curdled misanthropy.

But I should also hasten to add that no poet as good as Solie is the mere product of her influences. And I must confess that by spending so much time tracing her various aesthetic pedigrees, however interesting that investigation may have been, I’ve been derelict in what should have been my primary intention—of trying to define what makes her an original. So allow me to make a tentative attempt to reach that goal. Canadian poet Jim Johnstone, in an otherwise rather stilted assessment of Solie printed last year in Poetry, astutely praises what he calls her “carefully controlled unpredictability.” Despite her tendency to pursue quirky associative tangents, despite her wise-cracking persona, her poems possess a rich lyric and narrative precision. More importantly, they possess what Adam Zagajewski calls a “moral seriousness,” a stance that both reflects the bewildering complexity of contemporary culture and sternly condemns the ethical lassitude that arises from it. In this respect her poems are much like the work of Auden in his great period of the late 1930s: we are initially so impressed by the technical brilliance and wit of his writing that it takes some time for us to recognize the intensity of its moral outrage. And Solie, subtly but insistently, reminds us that there is plenty to be outraged about. The poems touch upon social injustice, ecological destruction, political chicanery (take a look at a merciless little poem entitled “The Prime Minister” and you can see why Hofmann likens Solie to Brecht), and our ADHD-addled addiction to the web—a realm of limitless data, factoids, and nattering, much of it pernicious and trivial. Solie is not so ideological a poet that she cares to posit solutions to these dilemmas. Her desire is instead to console us, and to allow us to draw some insights from her unflappable example. She is our cultural tour guide, fulfilling the role that Mandelstam tells us Vergil plays in The Inferno, always striving to “amend and redirect the course [of our seeing].” These are high claims, I know, but I make them without hyperbole. If you want evidence, allow me to look more closely at two fairly recent poems. One, “Life Is a Carnival,” is included in The Road in is Not the Same as the Road Out. The second, “Cave Bear,” appeared in the 2009’s Pigeon.

“Life Is a Carnival,” uses as its title another of Solie’s musical samplings—in this case she co-opts the name of a song by the Band, one with lyrics that decidedly belie the title’s apparent breeziness. Life may be a carnival, but for the Band this also means our masters are unscrupulous carnies. (My favorite lines in the song could have come from Solie’s own pen—“We’re all in the same boat ready to float off the edge of the world,” and “Hey buddy, would you like to buy a watch real cheap?”). The song is not so much about self-deception as it is about our puzzling nonplussed willingness to be conned. The poem commences innocently enough, but the subject of delusion soon becomes its controlling motif:

Dinner finished, wine in hand, in a vaguely competitive spirit

of disclosure, we trail Google Earth’s invisible pervert

through the streets of our hometowns, but find them shabbier, or grossly

contemporized, denuded of childhood’s native flora,

stuccoed or in some other way hostile

to the historical reenactments we expect of or former

settings. What sadness in the disused curling rinks, their illegal

basement bars imploding, in the seed of a Wal-Mart

sprouting in the demographic, in Street View’s perpetual noon. With pale

and bloated production values, hits of AM radio rise

to the surface of a network of social relations long obsolete. We sense

a loss of rapport. But how sweet the persistence

of angle parking!

As dramatic situations go, this one is priceless. “Dinner finished, wine in hand” leads us to suspect that the couple in the poem are readying for a tryst, or at the very least are snuggling up to a night with Netflix, but instead they tour their respective childhoods, courtesy of “Google Earth’s invisible pervert,” a characteristically inventive Solie trope—clever, but at the same time disconcerting. The couple is quickly disbursed of that quintessential human desire to see the past nostalgically. We’re offered “shabby” hometowns “denuded of childhood’s native fauna.” It’s all Wal-Marts and “disused curling rinks.” “Angle parking” may persist unchanged—but nothing else will. Yet the dose of reality which the couple is offered “in Street View’s perpetual noon” is too mediated and abstracted to register as realistic. (I’m also lead to wonder if Solie had Elizabeth Bishop as well as the Band in mind during the composition of this poem: the disconnect between a couple’s idealized wistfulness and an accurate perception of their past is examined in a fashion almost identical to that of Bishop’s “Over 2,000 Illustrations and a Complete Concordance.”) As the poem continues to unfold, the couple’s anxiety only intensifies:

Would we burn those places rather than see them

change? , or simply burn them, the sites of wreckage

from which we staggered from our formative injuries into the rest

of our lives. They cannot be consigned to the fourfold.

Though the age we were belongs to someone else. Like our old

house. Look what they’ve done to it. Who thought this would be fun?

This passage also offers us one of those shifts in diction that are a hallmark of Solie’s style. “The age we were belongs to someone else,” with its precise iambs and charged rhetoric, is immediately undercut by the vernacular (and pyrric-laden) “Who thought this would be fun?” This contrast, with its admixture of abjection and absurdity, is a perfect culmination of what the poem has been working toward all along. A lesser writer would have been tempted to end the poem here—but Solie carries on, and brilliantly. Here’s the conclusion:

A concert then. YouTube from those inconceivable days before

YouTube, an era boarded over like a bankrupt country store,

cans on its shelves, so hastily did we leave it. How beautiful

they are in their pouncey clothes, their youthful higher

registers, fullscreen, two of them dead now. Is this

eternity? Encore, applause, encore; it’s almost like being there.

This ending manages to be both cautionary and revelatory. The web is addictive in no small measure because it allows us to instantaneously dispel discomfort. A couple of clicks, and we can move from uncomfortable reckonings with our pasts to pure escapism. And it goes without saying that the web enables more monstrous segues to take place as well—were you so inclined, you could watch an Isis beheading video and immediately follow it with grainy footage of a pet doing something cute. Solie is canny enough to admit that she is as complicit in this state of affairs as any of the rest of us. But she also knows, as Pound would have said, “that what thou lovest well remains”—remains in this case through majesty of the Band during their final performance in 1976, as captured by Martin Scorsese in The Last Waltz, a film that has been rightly called the best rock documentary of all time. Never mind that this performance is being seen by a disgruntled couple peering into a tiny laptop screen, that the version of the film they are watching is likely a pirated one, that the Band are quaintly dressed in bellbottoms, flouncy shirts, and other cringe-worthy ‘70s regalia, or that two of the figures occupying the Winterland Ballroom stage on which they perform are now in their graves. (Sadly, with the death of Levon Helm, the number now stands at three.) And let’s remember that Solie is not a callow millennial who takes the clutter, benumbing over-stimulation, and maniacal web-surfing of the digital era for granted. No, to witness the abiding art of the past through a medium that the speaker is old enough to find estranging and compromised is not really “almost like being there.” But, on the other hand, it is as close to being there as we can venture. However fractured and debased, an aura persists, a rightness. It’s hard to read Solie’s closure as embittered. The poem’s final gesturer—and forgive me if I keep seeing so many overt literary homages in Solie’s work—is not so far removed from the closing of Frank O’Hara’s great elegy for Billie Holiday, “The Day Lady Died.” The couple may be sipping cheap chardonnay and watching ghostly figures on a 13-inch Mac, but the moment they experience is one in which, as O’Hara puts it, “everyone and I stopped breathing.”

If “The Last Waltz” is ultimately about what we preserve from the past, against all odds, “Cave Bear” is about extinction and the paucity of historical memory. Yet the poem also insists that nothing is so extinct or so forgotten that it cannot be exploited and commodified. (Tellingly, we eventually discover that the poem is set in Alberta, the site of those behemoth, stygian and ecologically toxic strip mines that turn tar sands into crude: the land not of drill, baby, drill, but of gouge, baby, gouge.) The poem’s opening reads like a send-up of a motivational speaker’s Power Point presentation, but then, in typical Solie fashion, everything soon gets wiggier:

The longer dead, the more expensive.

Extinction adds value.

Value appreciates.

This may demonstrate a complex cultural mechanism

but in any case, buyers get interested.

And nothing’s worth anything without the buyers.

No one knows that better than the United Mine Workers of America.

A hired team catalogued the skeleton,

took it from its cave to put on the open market.

retail bought it, flew it over to reassemble

and sell again. Imagine him

foraging low Croatian mountains in the Pleistocene.

And now he’s flying. Now propped at an aggressive posture

in the foyer of a tourist shop in the Canadian Rockies

and going for roughly forty.

One could hardly imagine a more bizarre journey than that of the skeleton from a cave floor in Eastern Europe to a high-end tourist shop in Alberta. This is cutthroat capitalism at its strangest, and a writer as erudite as Solie would likely know that the commodification of a cave bear skeleton is also a kind of spiritual profanation: mounted cave bear skulls are often found in the painted caves of Paleolithic Europe, among them Chauvet, site of the oldest cave art yet to be discovered.

The poem takes an even weirder and more surprising turn in its final stanza:

The pit extends its undivided attention.

When the gas ignited off the slant at Hillcrest

Old Level One, 93 years ago

June, they were carried out by the hundreds,

alive or dead, the bratticemen, carpenters,

timbermen, rope-riders, hoistmen,

labourers, miners, all but me, Stanley Bainbridge,

the one man never found.

Although the poem has suddenly swerved to a detailed description of a little-known historical disaster—in this case the Hillcrest, Alberta, mine explosion of 1914, which killed 189—I doubt if anyone encountering this passage for the first time would stop reading in order to do a web search on this event. As with Milton’s “On the Late Massacre in Piemont,” the impact of the description is so acute and visceral that we really don’t care about the historical circumstances—not at first, at least. Nor are we especially puzzled when Solie tells us, in the poem’s very last lines, that its speaker is one of the dead miners. As with “The Last Waltz,” Solie is unafraid to make a radical associative leap just as the poem seems ready to wind down. It is also a perfectly fitting gesture, yoking the Brechtian social satire of the opening to a specific human tragedy, and managing to link the demise the cave bear to the death of Stanley Bainbridge. The latter is an especially risky analogy. But Solie brings it off, and without willfulness or bathos.

When I read Karen Solie, I’m reminded of my first encounters with Berryman’s Dream Songs, Lowell’s Life Studies, or Vallejo’s posthumously published poetry. The books seemed unrelentingly astonishing, had a skewed but insistent sense of moral gravitas, and demanded a response that was as physical as it was intellectual. Just as importantly, the work immediately prompted a dumbfounded question—how did the writer do that? I look forward to asking that last question about Solie’s work for as long as she continues to write poetry. I see that I have now matched Michael Hofmann in extravagant comparisons, but so be it.

—David Wojahn

David Wojahn‘s ninth collection of poetry FOR THE SCRIBE, will be issued by The University of Pittsburgh Press in 2017. His FROM THE VALLEY OF MAKING; ESSAYS ON CONTEMPORARY POETRY was recently published by the University of Michigan Press. He teaches at Virginia Commonwealth University and in the MFA in Writing Program of Vermont College of Fine Arts.”

.

.

- Editor’s Note: Solie’s first two collections Short Haul Engine (2001) and Modern and Normal (2005) have always been available since their publication and available through Brick Books and through Amazon – Short Haul Engine is in its 6th printing while Modern and Normal in its 8th printing.↵

David, What a wonderful wide-ranging review/essay. Love that you cite Richard Hugo as being among the most significant poets to have emerged from the North American West. I”m looking forward to reading more of Solie’s work.

Dear David, I’m delighted, of course, but why would you ever doubt me?!

Stupendous.

Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds a legendary band, 3th best band ever, after Scorpions and Led Zeppelin (for me). “Into My Arms” http://lyricsmusic.name/nick-cave-the-bad-seeds-lyrics/best-of-nick-cave-the-bad-seeds/into-my-arms.html immortal song