The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel — most of us know what it looks like: God divides light from dark and land from water; God creates the Heavens, the sun, the moon; God holds his hand out to Adam’s hand and their index fingers almost touch; God creates Eve from Adam’s rib; the Snake, wrapped around The Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, tempts Adam and Eve with an apple; God expels Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden; eventually, after familiar stories of Old-Testament misbehavior, God sends a Flood. Meanwhile, sibyls and prophets sit at the edges, distracted by their own concerns. We know when the frescoes on the ceiling were painted: between 1508 and 1512. We know who the painter was: Michelangelo Buonarroti, born in 1475, died in 1564 (the year Shakespeare was born) – Italian painter, sculptor, architect, and engineer.

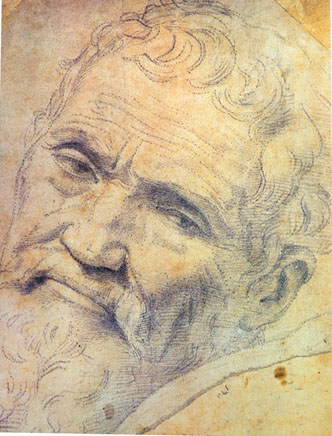

Sketch of Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra, 1533

Sketch of Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra, 1533

But do we know how the artist felt, lying on his back painting that ceiling month after month and year after year? I mean, do we know much about it beyond the imaginative retelling of it by a Hollywood director? We do, since Michelangelo himself gave us a poem about it:

…A goiter it seems I got from this backward craning

like the cats get there in Lombardy, or wherever

…–bad water, they say, from lapping their fetid river.

My belly, tugged under my chin, ‘s all out of whack.

…Beard points like a finger at heaven. Near the back

of my neck, skull scrapes where a hunchback’s hump would be.

…I’m pigeon-breasted, a harpy! Face dribbled-see?

like a Byzantine floor, mosaic. From all this straining

…my guts and my hambones tangle, pretty near.

Thank God I can swivel my butt about for ballast.

Feet are out of sight; they just scuffle round, erratic.

…Up front my hide’s tight elastic; in the rear

it’s slack and droopy, except where crimps have callused.

I’m bent like a bow, half-round, type Asiatic.

…Not odd that what’s on my mind,

when expressed, comes out weird, jumbled. Don’t berate;

no gun with its barrel screwy can shoot straight.

…Giovanni, come agitate

for my pride, my poor dead art! I don’t belong!

Who’s a painter? Me? No way! They’ve got me wrong.

Not many people know that Michelangelo was a prolific and accomplished poet, writing more than three hundred poems across the entire span of his creative life. He tried, near the end, to organize one hundred of his poems for publication. But one of the two friends involved in helping him with this project died before it was completed, and a first edition of the poems was not published until sixty years after the artist’s death, under the supervision (and high-minded tinkering and “sanitizing”) of Michelangelo’s grandnephew. “Sanitizing,” according to the translator John Frederick Nims, meant taking out “anything that might have reflected discreditably on the family or fame of Michelangelo: “Love poems addressed to a signor were revamped to fit the madonna of tradition; dubious political or religious views were amended.” His poems, to put it bluntly, were “made respectable.”

For more than 200 years, this version of the poems – “discretely doctored” to disguise the homosexual nature of them – was the only one available. By the mid-1800’s scholars began to look back at the originals for comparison; in 1893 the British homosexual activist and poet/critic John Addington Symonds offered a more authentic version, correcting the changed pronouns (from “she” back to “he”) and adding in several of the more explicit poems not included in the 17th-century edition. By 1960 a complete edition was published that included 400 pages of editorial notes referring to the originals.

What we recognize, as we read through The Complete Poems of Michelangelo is the unique physicality of the artist. He brings his knowledge of the body – it’s outer curves and inner musculature – with him, from the three-dimensional sphere into the verbal. Known to have reduced his skill at sculpting the human body to these instructive lines, “Carving is easy. You just go down to the skin and stop,” he also gave us these thoughts about sculpting, comparing what he sees as his simple talents (calling his own hammer “botched”) to the “heavenly hammer” of God:

….If my rough hammer shapes the obdurate stone

to a human figure, this or that one, say,

it’s the wielder’s fist, vision, and mind at play

that gives it momentum – another’s, not its own.

….But the heavenly hammer working by God’s throne

by itself makes others and self as well. We know

it takes a hammer to make a hammer. So

the rest derive from that primal tool alone.

….Since any stroke is mightier the higher

it’s launched from over the forge, one kind and wise

lately flown from mine to a loftier sphere.

….My hammer is botched, unfinished in the fire

until God’s workshop help him supervise

the tool of my craft, that alone he trued, down here.

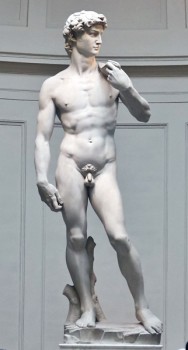

…………Michelangelo’s David

…………Michelangelo’s David

“Carving is easy. You just go down to the skin and stop.“

According to Nims, the originals were written on “whatever [Michelangelo] had at hand”: the backs of letters, records of expenses, receipts, and sketches for his buildings and for his paintings. The artist was known for his sloppy personal habits – Paolo Giovio, one of his many biographers, wrote, “His nature was so rough and uncouth that his domestic habits were incredibly squalid and deprived posterity of any pupils who might have followed him…he had a reputation for being bizzarro e fantastico.” He felt no particular restraints when he was young about criticizing the profit- and violence-driven culture that surrounded him in Rome:

….Chalices hammered into sword and helmet!

Christ’s blood sold, slopped in palmfuls. With the yields

from commerce of cross and thorns, more lances, shields.

Still His long suffering mercy falls like dew?

….These lands are lands He’d better not come through.

If He did, his blood would boil, seething sky-high,

what with His flesh on sale, in good supply.

Virtue? Cast out. NO ENTRY signs repel it.

Later in his life, he became more cautious about expressing his political views in public. But his love poems remained vital; he is described over the years by many poets, including Italy’s own Nobel laureate, Eugenio Montale, as one of the great lyrical poets of the High Renaissance.

No one translates Michelangelo’s poetry as well as John Frederick Nims – in fact, Nims’s essay about his translations engage the reader almost as much as the poems themselves. Nims had this to say about his own efforts:

I intended, at first, to [translate] only a few…. But when I had finished those few, the momentum carried me on through all eighty. Those done, there were the hundred or so madrigals, which showed another side of the poet’s temperament. They came next. Then there remained another hundred poems in various meters -but it seemed too late to turn back….What had kept me going, for a year or more, was the fun of it. “Fun” is a word that Robert Frost often used of poetry. If it offends anyone when used in the aura of the divine Michelangelo, as Vasari called him, we could retrieve from ancient Greece the favorite motto of Valery…which he translates as pour le plaisir. I kept translating for the pleasure of it.

Not all translation is word~for~word “literal,” rich in the pleasure we call “fun.” Dictionary~scavenging can be dreary work, like a piece of assigned homework we resent having to do. The fun comes in when, by imposing obstacles, we introduce the element of sport or game, with its hurdles, wickets, sand traps, baselines, strike zones, bull’s~eyes. So, in translating poetry, we have to cope with such tricky features as rhythm, sound, wordplay, connotation, and all the other enrichments that lift prose to a resonant and more allusive level. Incorporating as many of these features as the terrain allows is the goal of the translator: born of such fun is what we call fidelity.

Nims chooses a modern voice (“I don’t belong! / Who’s a painter? Me? No way! They’ve got me wrong”) which some critics object to. The poet Mark Jarman, in his review of the book for The Kenyon Review (Summer/Fall 2001) says that, as a translator, Nims “tends to heat up Michelangelo’s poetry, making it more inventive and slangier than it appears in Italian, closer respectively to the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins and Nims himself.” But in his introduction to the book, Nims points out the unappealing high diction of previous translators such as Wordsworth, Longfellow, Emerson, Santayana, Symonds and Rilke, all of whom overloaded the “rough language” of Michelangelo’s youth with too much elevated diction. He goes on to explain that previous translations had “a totally different effect on our ear today than Michelangelo’s would have had on the Italian ear of his time.” Despite their “complexity of content” the poems contain language that shows Michelangelo “spoke and wrote like the Florentine he was.”

The poems of Michelangelo surprise us. They do just what surprises should do: they wake us up and keep us marveling. To the list of his accomplishments – painter, sculptor, architect, engineer – we need to add the words “and poet.” Though publicly arrogant at times, in the privacy of his own poems Michelangelo doubted his own worthiness, his own talent, and he struggled with the uncomfortable fit between his creative energies and his more spiritual existence. Not only his back ached – so did his soul. The poems often sound like they come from a worried, tempestuous modern mind. See if you can get a copy of The Complete Poems of Michelangelo (translated by Nims) and read it through. And while you do, keep this image in mind:

—Julie Larios

Julie Larios has contributed several Undersung essays to Numéro Cinq over the last few years. She is the recipient of an Academy of American Poets Prize and a Pushcart Prize, and her work has been chosen twice for inclusion in The Best American Poetry series.

.

.

Handsome appreciation, especially because of the credit you give to Nims, one of the great translators of lyric poetry. His few translations of Sappho are magical and, like these of Michelangelo, utterly contemporary-sounding.

One correction, though: art historians agree that Michelangelo (despite The Agony & the Ecstasy) did not paint the Sistine ceiling lying on his back, but standing on the scaffold. If you look at his description of his physical contortions in the first poem quoted–

this backward craning. . . .

My belly, tugged under my chin, ‘s all out of whack.

…Beard points like a finger at heaven. Near the back

of my neck, skull scrapes where a hunchback’s hump would be. . . .

I’m bent like a bow, half-round

–it becomes clear that these postures are only possible if he is standing & leaning backwards. He wouldn’t be “backward craning” if he were lying flat. Irving Stone, screenwriter Philip Dunn, and director Carol Reed were all using their imaginations, as you say, by having him paint on his back (as well as in making him heterosexual).

Now you’ve got me intrigued, Jay. I’ll look into Michelangelo standing! Glad you liked the essay, and I completely agree with you about Sims – a master translator. I love what he says about striving for an “equivalent effect” rather than a word-for-word translation of a poem. I also love what he said in his Western Wind: An Introduction to Poetry about rhyme being something that forces the mind out of its ruts and into “mystery, magic, and imagination.” Maybe my next Undersung should be about Nims’s own work…?