It was a cold Friday afternoon, last December, the 18th. By the fire in my front room in Fredericton, New Brunswick (Canada), I called, via Skype, father and son tag team poets, Adrian and Matthew Rice. Adrian answered from his home in Hickory, North Carolina and Matthew from Carrickfergus in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. I was particularly interested in the father-son poetry connection and how much influence they had upon each other’s work, whether their writing processes were similar or not and how the poems unfolded for them. We spoke about their influences, why poetry was important to them and what advice, if any, Adrian would give to Matthew about the writing life. I also asked Adrian about Abbey Press, a poetry press he co-founded in 1997 which published critically acclaimed work from Irish poets such as Michael Longley, Gerald Dawe, Brendan Kennelly, and the late Hungarian poets, Istvan Baka, & Attila Jozsef among others. But first I wondered how a young boy from the Rathcoole housing estate, north of Belfast got interested in poetry and how he eventually found his way to North Carolina.

While the joys of technology made this international video-interview possible, the pains (or my lack of understanding) of this same technology resulted in my external microphone only working intermittently. My solution was to edit my voice out of the recording and allow Adrian and Matthew to speak for themselves which you will soon realise they are more than competent in doing.

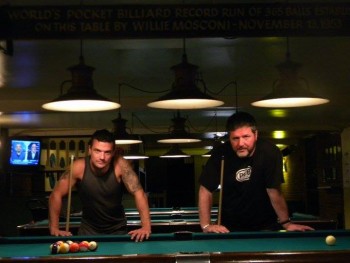

Following the interview are four poems from Matthew and four from Adrian (the first two are from his collection, The Clock Flower, and the last two from his recently published book, Hickory Station. Adrian is also one half of ‘The Belfast Boys’, an Irish Traditional Music duo – in between their two sets of poems, you can listen to The Belfast Boys’ rendition of The Blue Hills of Antrim)

—Gerard Beirne

..

Sparrow

Darkness was dwindling

As we arrived back at your house

At dawn, late summer ghosting

The curtained rooms,

To find two sparrows flying a frenzy

Around the place, having tumbled

Down the throat of the chimney,

Spewed into domesticity.

While you set about freeing the one

Downstairs, I followed the other

Up above and cornered it

Against the window in the study,

Butting frantically against the glass –

Hope as a symbol with all hope lost.

And it was then that I thought

That losing all hope was a renewal,

Like the petering-out of a season.

So, I offered it the last of my hope;

I opened the study window

And watched it disappear into sunlight.

.

The Hedge

in memory of Billy Montgomery

I’m a youngster

Led by the hand, as

The steam coming off the hob

Casts a cloudless shadow

Across the kitchen floor –

The smell of it like some old shanty

Billowing out its breath

Into the night,

Filling my field of vision

With a plume-tailed epiphany,

Holding the soul open

For the briefest moment,

Ebbing gently like the aftermath

Of passing through a rain-soaked hedge

Under falling cherry blossom –

As the window is opened

And the room restored.

.

Atreus and Thyestes

in memoriam Zbigniew Herbert

Wet-eyed and begging,

Thyestes’ sons are put under their uncle’s

blade. Clean-edged vengeance-giver,

Atreus separates them into pieces,

aiming carefully at the wrists

to make a clean sever,

and, at pains to preserve the dignity of the young faces,

makes a good stroke at removing their heads.

The heads and hands he’ll cauterise

and keep, holding in a single thought reason and grief.

And look, what a lavish feast he’s laid on

for his brother, who sits across

eating under the illusion of truce,

who, later, will take the long walk

to the Oracle, red-eyed and sickened,

through the honeysuckle hedges

and high-sided hollows,

stopping briefly along the way

to tickle his throat with a feather;

vomiting up his beloved children

amid the indifferent, dipping swallows,

the sweet scent of summer –

how cruel the life that continues on.

The cooling breeze and carefree sway

of high branches make playful shapes

in the setting sun.

.

The Gardener

It’s cool before the sun comes up

over Gethsemane, a single bird

singing like a wayward fan

during a minute’s silence.

The man out for an early morning stroll,

taking a piss under the drooping trees,

wonders briefly why the gardener in the distance

is not moving and is down on his knees.

—Matthew Rice

.

The Clock Flower

As far as the rest of the universe is concerned,

Maybe we’re like the feather-fluff of the clock flower,

The ghostly snow-sphere of the dying dandelion

That the child holds up in wide-eyed wonder,

Which the mother says to blow on to tell the time

By how many breath-blows it takes before the airy seed

All flies away, leaving her child clutching a bare stem.

And where our humanness might go, who knows?

And when it lands – takes root – what grows?

.

from ‘Eleventh Night’

XIX. Budgie

Drive the Demon of Bigotry home to his den,

And where Britain made brutes, now let Erin make men!

– from ‘Erin’ by William Drennan (1754-1820)

It seemed like every single house had one

Except us, though we had an aquarium,

The other housed comfort of the working class,

One behind the bars, the other behind glass.

I thought it odd that the underprivileged

Would happily keep something tanked or caged,

Considering our hard human condition.

I guessed it was our identification

With creatures as poorly predestined as we

Often believed our hand-to-mouth selves to be.

Keeping birds in seed is a real kind of love,

And sprinkling fish-flakes like manna from above.

………….Now by a strange quirk of imagination –

Some new light from within, something gene-given –

Every time I saw a map of Ireland

I rebelled against the usual notion,

The birds-eye, map-driven visualization

Of Ireland backed to the masculine mainland,

Her leafy petticoats eyed-up for stripping,

Her feminine fields ripe for penile ploughing.

Even as a child, I refused to see it

As a victim, back-turned towards Brit-

Ain, inviting colonial rear-ending.

I saw it as a battling budgie, facing

The mainland, proudly, prepared for what might come

Winging over the waves from the gauntlet realm.

Though couched by Drennan to properly provoke

His fellow Irishmen to throw off the yoke,

It was no ‘base posterior of the world’,

Arsehole waiting to be slavishly buggered

By a foreign foe even our side flinched at.

No more servile hung’ring for the ‘lazy root’,

But male and broad-shouldered as The Hill of Caves –

Where the United Irishmen first swore slaves

Would be set free by jointly overturning

The home-based kingdom of the sectarian –

Our bold-hearted budgie had come of age,

Had climbed the ladders and looked in the mirrors,

Then ignored the dudgeon doors and bent the bars,

Self-paroled, assuming independent airs.

………..So turned towards the royal raven of England,

To my mind, our Irish budgie was crowned

With the head of Ulster: the tufty hair of

Wind-blown Donegal, the brawn and brains of

Radical Belfast, the ‘Athens of the North’,

With the clear blue eye of Neagh, and beak of Ards,

Heart, lungs and Dublin barrel-bulge of Leinster,

The fiery feet and claws of mighty Munster,

And thrown-back western wings of mystic Connaught.

Four provinces, four-square, forever landlocked,

Friend of brother Celts, but full of righteous rage

Against the keeper of the keys to the cage,

The Bard’s ‘blessed plot’, his ‘precious stone set in

The silver sea’, his ‘dear, dear land’, his England.

Yes, no Catholic cage, nor Protestant pound,

Could hold my dissenting ideal of Ireland.

For in spite of spite, it was Drennan’s Eden,

‘In the ring of this world the most precious stone!’

His ‘Emerald of Europe’, his ‘Emerald Isle’

Which no vengefulness would finally defile.

.

Breath

What is death,

but a letting go

of breath?

One of the last

things he did

was to blow up

the children’s balloons

for the birthday party,

joking and mock-cursing

as he struggled

to tie all

those futtery teats.

Then he flicked them

into the air

for the children

to fight over.

Some of them

survived the party,

and were still there

after the funeral,

in every room of the house,

bobbing around

mockingly

in the least draft.

She thought about

murdering them

with her sharpest knife,

each loud pop

a perfect bullet

from her heart.

Instead, in the quietness

that followed her

children’s sleep,

she patiently gathered

them all up,

slowly undoing

each raggedy nipple,

and, one by one, she took his

last breaths into her mouth.

What is life,

but a drawing in

of breath?

.

Wasps

On an unseasonably

warm afternoon

I am back on the porch,

and the little wasps

are trying to build

in the hollow arms and legs

of my aluminum chair.

They’re determined,

as they are every spring,

to inhabit my chosen seat,

but I have soaked

their sought for portals

with gasoline, being equally

determined to stay put.

But on they come,

at regular intervals,

in one’s and two’s only,

as if one sometimes needs

the second as witness to carry

the story of occupation back

to the others, to be believed.

I wonder what they think of me,

and feel sorry for them,

almost guilty, even imagining

the dark openings they seek

as being cave mouths

in which they wish to store

some valuable scrolls.

So I am kind to myself,

reminding myself

that it’s my chair, my porch,

though I can hear them protesting

But we were here first!

Fair enough. But no matter.

For I have a porch thirst.

Gasoline will win the day,

for another year, anyway,

and I will sit safely and securely

behind my slatted battlements,

scratching the pale page

hoping, as always, to be

stung by poetry.

—Adrian Rice

.

Matthew Rice was born in Belfast in 1980. He has published poems widely in reputable journals on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as having his work included in the CAP Anthology, ‘Connections’. He is currently putting the finishing touches to his first collection of poetry entitled ‘Door Left Open’. He was long-listed for The Seamus Heaney Award for New Writing 2016. He is studying for his BA Honours degree in English Language and Literature. He lives, works and writes in Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland.”

Adrian Rice was born just north of Belfast in 1958, in Whitehouse, Newtownabbey, County Antrim. He graduated from the University of Ulster with a BA in English & Politics, and MPhil in Anglo-Irish Literature.. His first sequence of poems appeared in Muck Island (Moongate Publications, 1990), a collaboration with leading Irish artist, Ross Wilson. Copies of this limited edition box-set are housed in the collections of The Tate Gallery, The Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and The Lamont Library at Harvard University. A following chapbook, Impediments (Abbey Press, 1997), also earned widespread critical acclaim. In 1997, Rice received the Sir James Kilfedder Memorial Bursary for Emerging Artists. In autumn 1999, as recipient of the US/Ireland Exchange Bursary, he was Poet-in-Residence at Lenoir-Rhyne College, Hickory, NC, where he received ‘The Key to the City’. His first full poetry collection – The Mason’s Tongue (Abbey Press, 1999) – was shortlisted for the Christopher Ewart-Biggs Memorial Literary Prize, nominated for the Irish Times Prize for Poetry, and translated into Hungarian by Thomas Kabdebo (A Komuves Nyelve, epl/ediotio plurilingua, 2005). Selections of his poetry and prose have appeared in both The Belfast Anthology and The Ulster Anthology (Ed., Patricia Craig, Blackstaff Press, 1999 & 2006) and in Magnetic North: The Emerging Poets (Ed., John Brown, Lagan Press, 2006). A chapbook, Hickory Haiku, was published in 2010 by Finishing Line Press, Kentucky. Rice returned to Lenoir-Rhyne College as Visiting Writer-in-Residence for 2005. Since then, Adrian and his wife Molly, and young son, Micah, have settled in Hickory, from where he now commutes to Boone for Doctoral studies at Appalachian State University. Turning poetry into lyrics, he has also teamed up with Hickory-based and fellow Belfastman, musician/songwriter Alyn Mearns, to form ‘The Belfast Boys’, a dynamic Irish Traditional Music duo. Their debut album, Songs For Crying Out Loud, was released in 2010. Adrian’s last book, The Clock Flower (2013), and his latest, Hickory Station (2015) are both published by Press 53 (Winston-Salem).

.

.