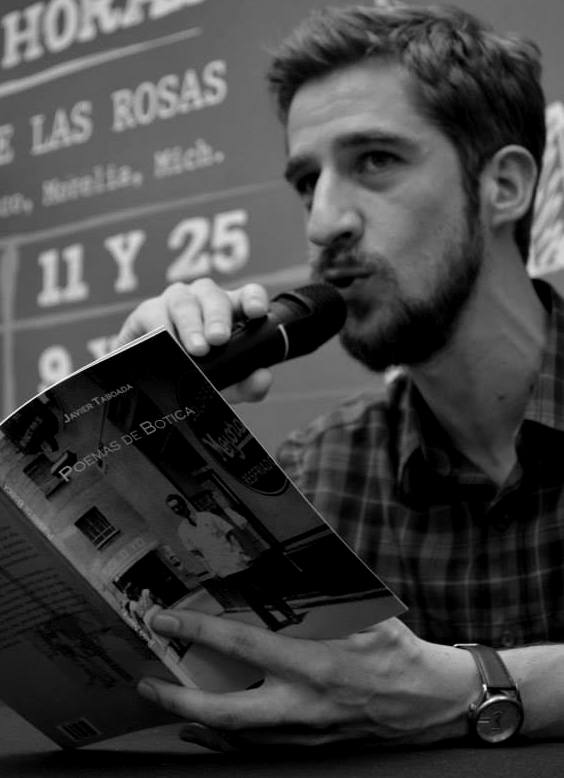

JAVIER TABOADA (Mexico City, 1982) is a translator and poet. He has translated the work of Alcaeus of Mytilene (Alceo, Poemas y Fragmentos, 2010) and Jerome Rothenberg (A Poem of Miracles and A Further Witness, forthcoming in 2016) amongst others. He is the author of a remarkable first collection of poetry, Poemas de Botica (La Cuadrilla de la Langosta, Mexico City, 2014). Dylan Brennan conducted this interview with Javier via email correspondence from October-December 2015.

DB: Tell us a bit about your early life, where you grew up, what you studied, how you first discovered poetry.

JT: I was born in Mexico City and grew up there. I studied at religious schools from primary through secondary before beginning a B.A. in Classical Literature at the Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), where I also completed my M.A.

I suppose that my first contact with poetry was similar to that of most middle class children at that time. What I mean by that is, with rare exceptions, in every house you could find certain books by certain poets such as: Neruda (his 20 poemas de amor almost always featured), León Felipe, Sor Juana, San Juan de la Cruz, Amado Nervo, García Lorca, Jaime Sabines anthologies, amongst others. But there were also plenty of anthologies of what we call poemas de declamación (recital poems): in my house we had the Álbum de Oro del Declamador (The Orator’s Golden Album), I still have it now. It’s a collection of occasional poems, ready to be opened for a mother’s birthday (or for the anniversary of her death), poems that speak of heartbreak, lost loves, poems to scorn vices, to exalt familial and Christian love etc., all tinged with a moral outlook and an unbearable sentimentality. However, in the final section of this book, I found poems like Eliot’s Hollow Men, Lermontov’s The Cross on the Rock, Pasternak’s Night, The River-Merchant’s Wife: A Letter by Ezra Pound, Quasimodo’s Auschwitz, to mention just a few. The one I liked best from this book was Antonio Plaza’s A una ramera (To a Harlot) because the use of language made me laugh.

The other contact with poetry came from a source less bookish (for want of a better word), I mean popular Mexican music, especially the bolero. Then later, during puberty, rock music.

Beyond what I’ve mentioned, I wasn’t very interested in reading poetry until the age of about 16 or 17. And that had quite a bit to do with the so-called Contemporáneos poets. Xavier Villaurrutia, Salvador Novo, some of Carlos Pellicer’s stuff, José Gorostiza, Jorge Cuesta (his sonnets, of course, not his Canto a un Dios Mineral, which I could only begin to comprehend—years later—via an extraordinary book by Evodio Escalante). They astounded me. After a certain amount of time, I then began to buy poetry books or to read them in the school library, whenever I’d been kicked out of physics or mathematics class. My reading is completely disordered. I’m a trained Hellenist and I haven’t even been able to follow any kind of order with the Ancient Greeks.

DB: I know you translate quite a bit. Tell us about that. Does translation affect how you write, how you read? Do the poets you translate influence you much? Which poets have influenced you? How did you come into contact with them?

JT: Nowadays I read as a translator and this has become beneficial to me. In my current state of disorder I’m reading and translating Rosmarie Waldrop, Federico María Sardelli, Claudia Rankine and John Wilmot. I read them, then I attempt to translate a certain fragment, then I read them again, etc., until the job is done. Whether the translations get published or not, this permits me to be influenced in a way by their work, to assimilate something of their poetics, and, in some way, to redesign my own, to become re-moulded. I am in no way scared of continual influences (I don’t think they ever end) nor of revealing them to others. It is obvious that translation, as reading or as a constant act, not only modifies one’s own voice, but also changes literary traditions. One day, those who study the national poetry of certain regions will pay more attention to the translated works that their poets have read as opposed to the original versions. For example, I read Eliot translated by Ángel Flores and, in my memory, The Waste Land (La Tierra Baldía) is the one that Flores translated.

As I mentioned, I’ve been greatly influenced by the Contemporáneos. My reading of the classics, which I did almost exclusively for a period of about seven or eight years, has also left its mark. Fundamentally, the ancient lyrics: Alcaeus (whose work I translated almost in its entirety in 2010) but also Sappho and Alcman; and also Archilochus and Hipponax. The latter I consider the most modern due to his use of language and humour. His pugilistic poems are raw, his sexual references, explicit. For example, there is one poem in which the “poetic voice” attempts to cure his impotence with the assistance of a Lydian witch. Frankly, it’s hilarious, vulgar and ingenious. Among the Greek Classics I should also mention that I read Euripides and Aristophanes thoroughly.

There are common names such like Pound, Eliot, Wordsworth, Apollinaire, Rimbaud, Pessoa, Hölderlin, Yeats. Of course, they have influenced me. More specifically, I can mention poets like Blake, H.D., Charles Wright, David Meltzer, William Carlos Williams, Lee Masters, Efraín Huerta, Rubén Bonifaz Nuño (I regards his Fuego de Pobres as a gem of Mexican literature) and Nicanor Parra.

Finally, I would like to draw attention to the influence of Jerome Rothenberg. This is due, in part, to the fact that, in the last year and a half I have worked a lot with him. I’ve finished translating A Further Witness and A Poem of Miracles, two of his most recent collections. It looks like they’ll be published in bilingual editions this year (2016). I’ve also translated to Spanish and to Ladino (the language of the Sephardic Jews) his poem Cokboy which is, as you may know, written in a mixture of English and made-up Yiddish. This proximity (admirably generous) has transformed my understanding of his poetry. I will remain forever grateful to him.

DB: Is there a Mexican poetic tradition? Are there various? With which, if any, do you identify? What about the Mexico City cronistas (non-fiction chroniclers like Carlos Monsiváis or, most recently, Valeria Luiselli)? I ask because your book Poemas de Botica (Apothecary Poems) is very much steeped in the sights, smells, sounds of a particular part of the city.

JT: Everywhere, particularly during these years of globalisation, the borders between “national” literatures have begun to dissolve: they begin to respond to different stimuli and contact with other poetic tasks become more immediate. In Mexico right now I can see a conceptual growth as well as a turn towards new technologies. On the other hand I see an emerging interest in ethnopoetry, ecopoetry and colloquial poetry. Much of this owes to the incorporation of the North American poetic tradition or English language poetry in general.

As a tradition, I would have to mention the baroque. It’s still alive and has continued to adapt (in some instances, in other instances, frankly, it has not) to the times. In its use of language, for example, can be derived part of the metaphysical or mystical poetry that is composed in Mexico.

I don’t know to what extent I can associate myself with any “tradition”. It seems to me that that should be decided by others. I can only recognize some influences that are present in this book, but I cannot talk about belonging. Sophocles says that nobody should consider a person as being “happy” until the moment of his/her death. Other work will come, I hope. Then the time will come for me to cash out. Time will take care of putting everyone in their place. What I mean is, to answer your question, there are a wide variety of poetic traditions in this country. I’m sure there are others which I’ve forgotten, or am yet to have discovered.

Of the cronistas that you mention, I haven’t read Luiselli. I’ve read very little Monsiváis and a bit more of Novo. Honestly, the Mexico City chroniclers had very little influence in Poemas de Botica. I think that a much greater debt is owed to the Lyrical Ballads, to Huerta, Parra, Salvador Novo’s Poemas Proletarios, Fuego de Pobres by Bonifaz and Lee Masters’s Spoon River Anthology. After the collection had been published I was introduced to Chetumal Bay Anthology—a very interesting collection by Luis Miguel Aguilar (winner of the 2014 Ramón López Velarde Prize)—and noted the similarities between my book and his (the focus on just one place, the style of language etc. which in turn is fed by the work of Masters). A fortunate coincidence.

Mexico City has a great deal of problems: brutal inequalities, violence, organized crime (though they claim it’s not there), racism and discrimination, misery belts, inefficient transport, unstoppable pollution etc. On the other hand there are the personal oases, those places that transform the city into your city, though you will always need to pass through chaos to get there. A bit like Milton’s Lucifer. This dichotomy is experienced by anyone who has lived in the D.F. In my case, I couldn’t stand it any more so I left.

DB: Tell us about how you write. Where does it all come from?

JT: I don’t have any particular schedule or discipline for writing. In reality, all my writing springs from obsession. After investigating a certain theme for a while, disposing of material, etc., ideas emerge. And then begins a process that is long. As you well know, there are texts that just jump onto the page and others that take forever. Then, when I believe that a certain text is speaking, I correct it, edit it. I throw away or erase what is no longer of use, without restraint. Usually, what I leave behind is the poem’s skeleton. When I’ve found—sometimes it’s just a few verses—the idea, the tone, the form of what I want to say, I begin to re-write it. In the end, I share it with some writers that I know and trust to be objective. Then, if the text passes this test, I think it’s ready. In general, I mistrust my own opinion. With regard to form, the form is dictated by the contents of the poem.

DB: Poemas de Botica is an admirably solid collection. By that I mean that it possesses a wonderful unity, all the poems revolve around your grandfather’s apothecary and it’s a collection that feels more like a place than a book to me. I mean that in a good way, it’s remarkably vibrant, alive. Where did it come from? Did you always know how it would be structured?

JT: Poemas de Botica emerged from the Guerrero neighbourhood, one of the oldest and dodgiest in the city. But, to be more precise, from the area immediately surrounding the Dr. Medina pharmacy which was the property of my grandfather for almost 65 years. The pharmacy also operated as an old-style apothecary. I had to work there for about 4 or 5 years, selling medicines and mixing remedies (not many, in reality), while I studied at university. The apothecary is still open, even today.

No, actually, it’s strange. Some of those poems (which were then called de Botica in 2003), were more or less finished. But I didn’t know what to do with them. I thought they’d never be published. You know, I didn’t have any more material. There were 4 or 5 poems and that was it. Then, I stopped working there, and I stopped writing poetry and focused on my studies. I submitted, like we all do, to that sterile prose of academia. And, while it gave me other positive things, it dried up my literary work.

I found it really very difficult to start writing again. A few years later, I’d say it was around 2012, I started to re-write those poems, now with the readings I mentioned above in my mind. The key to the collection arrived with the (Homeric) Cantos del Señor Olivares: I glimpsed the possibility of orchestrating the whole book with an array of different voices: the historical voice of the city (Olivares), the lyrical voice (the Apothecary), the testimonial voices of the characters, all mixed up: humour, violence, colloquialisms, music and refrains. In other words, everything that I learned in Guerrero. And then I quickly discovered that the book was finished. Leticia Luna, the editor, insisted that the tone was not lost.

Finally came the business of unifying the collection. All the poems revolve around an apothecary. I understood that it was about the day-to-day running of the business. Working at an apothecary, you end up having to deal with the clients, with yourself, with those who promote the merchandise, with anything that was going on in the barrio. Outside and inside. And almost everything that happened in that small world is portrayed in the book. ‘The world is an apothecary of the depraved’ (El mundo es una botica de viciosos) says the book’s epigraph. The world or purgatory in which we all find ourselves. In fact, the first poem gives the physical location, the address of the pharmacy, but this also functions as a cosmic location of the Counter-Earth, according to an astronomy book by Giorgio Abetti, I think. That’s what the botica was for me.

DB: What do you think of contemporary Mexican poetry?

JT: Honestly, and this has a lot to do with my formative period, I’ve attempted to immerse myself in contemporary Mexican poetry only recently, in the last three or four years. For example, I have discovered fantastic works such as those of Francisco Hernández (Moneda de Tres Caras, La Isla de las Breves Ausencias), Elsa Cross (Bomarzo, Bacantes, Canto Malabar), Myriam Moscona (Negro Marfil and Ansina), Coral Bracho (Si ríe el emperador), José Vicente Anaya (Híkuri), Ernesto Lumbreras (Lo que dijeron las estrellas en el ojo de un sapo), Tedi López Mills (Muerte en la Rúa Augusta and Parafrasear) Gerardo Deniz (who had already passed away but his Cuatronarices was a major discovery for me), Luis Miguel Aguilar, as I already mentioned, the Mazateco poet Juan Gregorio Regino (No es eterna la muerte), Víctor Sosa (Nagasakipanema), amongst others.

There are some writers, a bit younger than the ones I just mentioned—often younger than I am—whose work I admire. Amongst these I can mention Alejandro Tarrab, Hugo García Manríquez, Balam Rodrigo, Inti García Santamaría, Heriberto Yépez, Hernán Bravo, Yuri Herrera, Óscar David López, Sara Uribe, Paula Abramo, Marian Pipitone, Eva Castañeda, Zazil Collins. So far. I know of many other names due to the renown they have earned but I haven’t read them, and that is a source of minor embarrassment. But that work is pending. The list will certainly grow.

DB: Personally, in Mexico, I’ve noticed a fair amount of literary cliques. As if the on-going feuds like the ones documented so memorably by Bolaño in his Savage Detectives are continuing today. Do you notice any of this? Does it hold interest?

JT: Yes, I suppose that, like everywhere else, there are. Regional, local, national, transnational. In general, I have very little time for personal disputes that always seem to mutate into group disputes. I read, ignoring the affiliations or ascriptions of an author. I’m only interested in the text. I can still identify the conflicts generated by the aesthetical (and political) differences between the Stridentists (Estridentistas) and the Contemporáneos or between the Infrarrealistas (the “Visceral Realists” from Bolaño’s Savage Detectives) and group of poets headed by Octavio Paz. Or the ongoing arguments between nationalism (whether that be criollo or mestizo) of Mexican poetry against its francophilia (afrancesamiento as Cuesta called it, extending the term to mean a sort of universalist ambition).

DB: There seems to be plenty of political poetry being written and disseminated in Mexico of late. What do you think of this? Should poetry be political?

JT: Yes, it is normal to see this emergence of political poetry. We live in tragic times. Some of these poems I simply don’t like: particularly those that seek to mythologize or ritualize that which has happened in Mexico. By so doing, they seem to engender a justification (myths and rites that outline a psychic, hegemonic and social mechanism a posteriori) in order to suggest some sense of destiny. Furthermore, I think that political poetry (as always) is at risk of turning into a simple instrument of affiliation, an occasional militancy that is of more benefit to the poet than to society.

A work that stands apart from these is Antígona González by Sara Uribe. Though she recycles the figure of Antigone, she refuses to justify suffering through the notion of myth.

DB: What’s next for you? What are you working on now?

JT: Well this year (2016), as I mentioned, I hope to see the Rothenberg collections published. I also hope to publish Nacencia, a long poem dedicated to my son, which focuses on the processes of translation. It’s about the impossibility of translation. It’s also a unified piece, from the eve of his birth up until an event that seemed astonishing to me, which occurred when he was about four months old. He reached out to touch the shadow of his own hand on the wall. In other words he carried out his own process of translation: in four months he had interpreted the world, his surroundings, passing through a long phase of discovery and an awakening of the senses, until he could see that hand and touch it. From that point, everything became clear, the light of the allegory of Plato’s Cave. Nacencia is a poem that has nothing to do with, with regard to subject matter or form, Poemas de Botica. Which is something that pleases me greatly.

Furthermore, I want to continue with my translations of Claudia Rankine (her multi-prizewinning Citizen) and of Rosmarie Waldrop (The Ambition of Ghosts). I’d also like to keep translating some of Federico Maria Sardelli, who is real character (Vivaldi scholar, director of Modo Antiquo, painter, poet).

—Javier Taboada & Dylan Brennan

.

From Poemas de Botica (Apothecary Poems)

By Javier Taboada

Selected and translated by Jack Little.

.

Visión

Aquí

las rameras

……….se canonizan en nueve meses

el diente de oro

es tatuaje de honor por las migajas

y el rito de la madre

es zumbarse al niño

y llevarlo a la escuela

cubriendo el látigo del marido.

Los boticarios

son los nuevos curas

que redimen

por menos del tostón.

La borracha canta

soy la Magdalena

revolcada en mierda

……….hay viejos oraculares

……….héroes y padrotes

y hasta los boxeadores rezan

que con la Virgen basta

y la piedra sosiega.

Aquí

la camisa de fuerza

espera por la señal de la cruz.

.

Juanito

Nadie sabe que soy un súper héroe.

Piensan que estoy loco

pero en las noches vuelo

……….aunque todavía

no aprendo bien

y me azoto en la banqueta.

De día

enjuago los carros

que llevan a los reyes actuales.

Mas luego oscurece

……….y no sé quién

le sube el switch

a mis rosas eléctricas.

Ahí me da por encimarme

……….los calzones

……….la capa

mis botas negras de hule

y entonces VUELO

por la quijada brillante

del burro

la tripa de cristal

que se hace rollo

y se alarga.

Eso que dicen

que es la epilepsia.

Y con mi lengua

en la banqueta

me quedo dormido

……….como una coca de vidrio

vacía de la furia del mar.

.

Crac

Un joven de quince años

pidió un gotero de cristal

para bajarle a su bebé la temperatura.

…………Mejor uno de plástico

…………que el vidrio es peligroso

…………si el niño tiene dientes.

No lo quiebra no lo rompe.

Y besó una cruz

que hizo con los dedos.

………….Fui por su jarabe

y me dejó hablando solo

con la medicina.

Nunca había visto a un tipo tan flaco.

***

La piedra

el fumado

…………en papel

…………en lata de refresco

…………o gotero de cristal

es un tizón de sesenta pesos

…………llaga que arde viva

…………entre labios y garganta.

Hay que jalarle duro

…………fumarse hasta las burbujas

…………oír el crac en la piedra

y sentir cómo pega en putiza.

***

Pasadas las diez de la noche

chupando la mugre de las uñas

…………por si algo sobra

los muchachos del crac

…………ángeles de cera sobre una flama

salen a la calle

con todas las palabras

…………………en la manguera de la lengua

el sexo de fuera y erecto.

El barrio cierra sus ventanas

…………tapia sus puertas

porque los muchachos del crac

…………aúllan

y se rascan para quitarse los piojos

…………que inundan su piel

……………….pues es mejor dejarla en carne viva

…………a que se la coman los gusanos.

Los muchachos del crac

…………ejército de cadáveres sin camisa

…………pubertas embarazadas

caminan a ninguna parte

…………juegan volados o rayuela

…………cantan bajo la pequeña luz del encendedor

y miran de reojo

buscándose el cuchillo.

Luego caen

uno por uno

bajo los dedos del alba.

***

Al abrirse las puertas del metro

los muchachos yacen en el piso

………………como pan con hongos

……………………..arcada del ebrio

……………………..viejo al que chupó el diablo.

—Javier Taboada

§

Vision

Here

the whores

………….are canonized in nine months

the gold tooth

a tattoo to honour crumbs

and the rite of the mother

is to hit her child

and to take him to school

to cover up her husband’s lash.

The apothecaries

are the new curates

redeeming

for less than fifty cents.

The drunk lass sings

I am Mary Magdalene

wallowing in shit

…………here old oracles

…………heroes and pimps

and even the boxers pray

that the Virgin alone will suffice

and the crack rock soothes.

Here

the straitjacket

waits for the sign of the cross.

.

Juanito

Nobody knows that I am super hero.

They think I’m crazy

but at night I fly

……………even though still

I don’t learn all that well

and crash into the sidewalk.

By day

I wash the cars

that carry today’s kings.

After dark

………….I don’t know who

flicks the switch

on my electric roses.

I turn myself out in

……………underpants

……………the cape

my black rubber boots

and then I FLY

by the brilliant jawbone

of the donkey

the glassy guts

that roll

and lengthen.

That they say

……………is epilepsy.

And with my tongue

on the sidewalk

I sleep

……………like a glass bottle of coke

empty of the fury of the sea.

.

Crack

A fifteen year old guy

asked for a glass dropper

to bring his baby’s temperature down.

……….Better a plastic one

……….glass is dangerous

……….if the kid already has teeth.

He won’t crack it won’t break it

and he kissed a crucifix

made with his fingers.

……….I went for the syrup

and he left me talking alone

with the medicine.

I had never seen such a skinny fella.

***

The stone

devilsmoke

……….on paper

……….in a can of pop

……….or a glass dropper

it’s a three buck ember

……….a sore that burns alive

……….between the lips and throat.

You have to pull hard

……….toke until it bubbles

……….hear the crack in the rock

and feel it like the smack in a brawl.

***

Past ten at night

sucking the muck on their nails

……….just in case there’s something left

the crack boys

……….wax angels over the flame

go out into the street

with all the words

…………..on the tube of their tongue

sex outside and erect.

The neighborhood closes its doors

……….shuts its windows

because the crack boys

……….howl

and scratch to get rid of the nits

……….that fill their skin

……………for it’s better to leave it raw

……….than let it be eaten by worms.

The crack boys

……….army of shirtless corpses

……….pregnant adolescents

walk nowhere

……….play coin toss or hopscotch

……….sing under the dim glow of a lighter

and gaze askance

looking for a knife.

Then they fall

one by one

under the fingers of dawn.

***

As the metro doors are opened

the boys are lying on the floor

………………..like moldy bread

…………………….drunk’s retch

…………………….an old man made rotten by the five-second rule.

—Javier Taboada translated by Jack Little

.

Javier Taboada (Distrito Federal, 1982) traductor y poeta. Ha traducido a Alceo de Mitilene (Poemas y Fragmentos, 2010) y a Jerome Rothenberg (A Poem of Miracles y A Further Witness, de próxima aparición), entre otros. Es autor de Poemas de Botica (2014).

Jack Little (b. 1987) is a British-Mexican poet, editor and translator based in Mexico City. He is the author of ‘Elsewhere’ (Eyewear, 2015) and the founding editor of The Ofi Press: www.ofipress.com

Dylan Brennan is an Irish writer currently based in Mexico. His poetry, essays and memoirs have been published in a range of international journals, in English and Spanish. His debut poetry collection, Blood Oranges, for which he received the runner-up prize in the Patrick Kavanagh Award, is available now from The Dreadful Press. Twitter: @DylanJBrennan

.

.