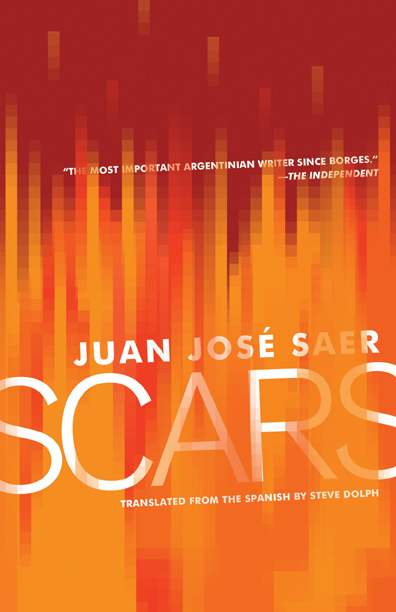

Herewith, an excerpt from Juan José Saer’s novel Scars (originally published in Argentina in 1969). Open Letter Books has released a new English translation from Steve Dolph. Saer, who died in 2005, is considered one of Argentina’s most important writers, alongside Juan Luis Borges and Julio Cortázar. Saer was a prolific writer of novels, stories and criticism. For much of his life, he lived and worked in France, and the theme of exile is prevalent in his writing. Saer also blurred genres, a technique especially prevalent in Scars. With equal dexterity, he blends the influence of Dashiell Hammet with that of Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Scars might well be read as four linked novellas. In each of the four sections of the book, a different narrator recounts the events surrounding a brutal murder which takes place on the streets of Santa Fe, a small city along the Parana River in northeastern Argentina. In the section excerpted below, the second in the book, the narrator is Sergio, a non-practicing lawyer who writes occasional essays (“Professor Nietzsche and Clark Kent”) but who mostly gambles. Sergio’s obsession is baccarat. His entire existence seems centered around the system he has worked out for playing at the baccarat table. It’s not so much about winning or losing to Sergio, but about being in the game, about being at the table when the cards are dealt. “In baccarat I saw a different order, analogous to the phenomena of this world, because that other world, the one in which the opposite face of every present moment is utter chaos, and in which the chaos, reinitiated, could erase all the present moments behind it, just like that, seemed horrible to me.” Sergio gambles with a mad fever. Watching him at the tables, your heart races as he throws down the last of savings. You feel that gambler’s high when he goes on a winning streak. You shout at the pages, trying to talk sense into this philosopher-madman as he puts up the mortgage on his house in order to have one more night of baccarat. “Every bet is desperate because we gamble for one single motive: to see.”

–Richard Farrell

Mostly I played baccarat, because there my past was predetermined. Once in a while it could change, but it felt more solid than the crazy mayhem of the dice in the shaker, better than the blind senselessness of their flight before they came to rest on the green felt. My heart would tumble more than the dice when I shook the cup and turned it over the table. You can’t bet on chaos. And not because you can’t win, but because it’s not you who wins, but the chaos that allows it.

In baccarat I saw a different order, analogous to the phenomena of this world, because that other world, the one in which the opposite face of every present moment is utter chaos, and in which the chaos, reinitiated, could erase all the present moments behind it, just like that, seemed horrible to me. That’s what I felt whenever I shook the dice. In baccarat, my eyes could follow every movement the dealers made as they shuffled the cards and reinserted them into the shoe. First they would spread them out over the table, and then stack them in piles organized in three or four rows. They’d combine all the piles into a single column, two hundred and sixty cards, five decks in all, and drop them into the shoe. Then the game would start. First you had to think about the cards in the shoe. In baccarat, when the player is dealt a five—made up of a face card and a five, a three and a two, a nine and a six, or any other combination—he can choose whether or not to hit in order to improve his score. If the player hits, the entire makeup of the shoe changes. Before, I said that in baccarat I had a predetermined past. But it’s probably better to say I had a predetermined future. Objectively speaking, the cards in the shoe are actually a past. For me, ignorant of their arrangement, they become the present and then the past as they are dealt, two at a time. At that point they become the future. And the player’s decision when he lands a five—hitting or standing—changes the cards. But the present is necessary for that change to take place.

So the dealer’s shoe, its cards arranged in a way that could be completely reorganized by a subjective decision to take a single card, is at once a predetermined past and a predetermined future, and at once determined and changeable according to the player’s decision to hit on five or stand.

Every hand was the present, but with the shoe there in the middle of the table both the past and the future were also the present. The three coincided. All three overlapped on the table. Once played, the two cards from that hand moved to a pile of cards face up next to the shoe, the cards that had been used in previous hands. They formed, in this way, another past. Several relative pasts were thus formed: the past of the discards piled face up next to the shoe; the past in the shoe, which was also the future; and the pasts of the rearrangements suffered by the shoe according to the gambler’s decision to hit on five or stand.

Several futures coincided as well: the future of the shoe as initially arranged, as well as every future determined by the player’s decisions to hit on five or stand. Because the decision to hit was always present, always future, until the decision to hit, standing, you could say, was also a rearrangement.

Every hand was thus a kind of bridge, a crossroads where distinct pasts and futures were exchanged, and where, at its center, all the presents were collected: the present of the current hand, momentary, transitory; the present of the past of the pile of discarded hands; the present of the past of the shoe as it had been arranged initially; the present of the past of the shoe, now that, objectively speaking, the shoe was both a determined past and a determined future, and at once a past and a future from which rearrangement could be dealt.

And with each hand the different pasts and futures would coalesce and intermingle: for example, the first four cards dealt, two to the player and two to the banker—which could reach as many as six each if the player and the banker failed to reach the minimum score (four)—belonged to the past, or the future, of the dealer’s shoe: they originated from the two hundred and sixty cards stacked up inside the shoe and nowhere else. And the pile of cards face up next to the shoe consisted of cards that had originated in the shoe, and which had briefly been the deal—that absolute, coalesced present, which my eyes had seen on the table. A narrow relationship, therefore, unified all the states.

Also present were the precedent chaos, the coincident chaos, and the future chaos. The three coincided, actively or potentially. The precedent chaos coincided with the organization suffered by the cards in the shoe, and rematerialized as the coincident chaos represented by the cards that were piled face up next to the shoe, which it coincided with. And this chaos would undergo a transformation similar to the first—when the dealers shuffled the cards, organized them into several even piles, and combined them, ultimately, into a single column of two hundred and sixty cards before dropping them into the shoe. The precedent chaos was present in this act, as the organization of the shoe was determined by it. The future chaos, at once active and potential since it took shape from the chaos of the cards piled face up next to the shoe—and therefore consisted partly of this chaos and could only come from it—would ultimately be indistinguishable from this—the precedent—chaos and from the coincident chaos, since chaos is in itself indistinguishable and essentially singular. Each chaos was also the future chaos, and the arrangement of the cards and the transitory present of the deal were also part of the future chaos, since they would soon become it. And the three mutually coincident states of chaos, meanwhile, were coincident with the arrangement of the shoe, the present of the deal, and all the intersections of the past and the future that had been, were, or would be coalesced in it.

Each time the shoe resets, having passed through the original chaos in which the dealers’ distracted hands spread the cards in random piles over the table, a new arrangement is produced. As many possibilities for its arrangement exist as there are possibilities for arrangement among the two hundred and sixty cards, each one a fragment of the original chaos submitted to an organization by the reflexive movements of the dealers’ hands. As I see it, no arrangement could be identical to another, and even if in two of the arrangements the cards fell in the same order, the first arrangement still wouldn’t be the same as the second, and for this reason: it would be, in effect, another. On the other hand, it wouldn’t seem the same. There wouldn’t be a way to verify it. The task—a tedious and hopeless waste of time—would be dismaying from the start. And in any case, only the initial arrangement would resemble the other’s. Which is to say, only a given pathway or portion of the process could resemble a pathway or portion of the process of the other arrangement.

Because the other pathways or parts wouldn’t be the same. For that to happen, the following similarities would have to occur: first, the way the dealers shuffled would have to be exactly the same both times, and the way the cards were arranged would have to turn out exactly as before. A five of diamonds that appears in the shoe between a three of diamonds and an eight of clubs would need to come to occupy this location by the same itinerary as before—above a four of spades and a king of diamonds, under a queen of clubs, between an ace of hearts and a two of hearts, for example—something which, of course, is impossible to verify.

Also: every player dealt the five would have to choose the same in every case in each of the arrangements. Bearing in mind that there are players who tend to stand, and players who tend to hit sometimes and other times not, and players who tend to follow their gut when the cards are turned over, the possibility of repetition becomes practically impossible.

Finally: the pile of cards face up next to the shoe would have to be a arranged in the same way as the pile formed by the discarded hands of the previous arrangement. But that arrangement, because no one controls it, is impossible to verify.

In baccarat, ultimately, repetition is impossible.

— Juan José Saer (English translation by Steve Dolph)

———————————–

Juan José Saer (1937-2005) was a celebrated Argentine novelist and writer. He moved to Paris in 1968 and became a lecturer at the University of Rennes. He wrote numerous novels and short story collections as well as critical studies on literature. Winner of Spain’s prestigious Nadal Prize, several of Saer’s novels have been (or will soon be) translated by Open Letter Books.

See also Richard Farrell’s review of Scars here, also his review The Sixty-Five Years of Washington and an excerpt from that novel here. Read an interview with Steve Dolph, Saer’s translator.