/

A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by statesmen and philosophers and divines. If you would be a man, speak today what you think today in words as hard as cannon-balls, and tomorrow speak what tomorrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict everything you said today.

-Ralph Waldo Emerson

/

My car has a factory-installed blind spot detector, a system that the manufacturer, Volvo, calls BLIS, or Blind Spot Illumination System. (The actual device, fortunately, works better than the acronym.) It consists of a camera mounted below the mirror that is wired to a tiny orange light inside the car. The dime-sized, triangular light illuminates when another vehicle is moving somewhere in my car’s blind spot. I’ve grown quite fond of BLIS, quite accustomed to the orange glow, especially in the dizzying commutes on Southern California freeways. It’s a helpful aid. A cheat, if you will, a machine doing the vigilant work that the driver is supposed to do. With only a quick glance at the side mirrors, my peripheral vision catches the orange light and I know that something lurks in those hidden spaces.

I wonder what it would be like to install an automated blind spot detector on myself, BLIS for the soul, illuminating the parts I fail to see. What would such a device show? Would it light up when my hot temper flares, or when I’m impatient with my kids or insincere with my wife? Perhaps it would reveal buried things about my desires, expose my snap judgments toward other people, or render visible my hidden fears and anxieties. How embarrassing it would be to have at a party, in a room full of strangers, glowing as a boorish lawyer droned on about his wonderful job, or lighting up like Rudolph’s nose on Christmas Eve as a pretty woman crossed the room. But if I’m already aware of these shortcomings, even in brief, then maybe that’s not what this blind spot detector would do at all. Maybe it would only flash on when least expected, revealing aspects of myself I can’t see, or don’t want to. How often would that little orange light glow?

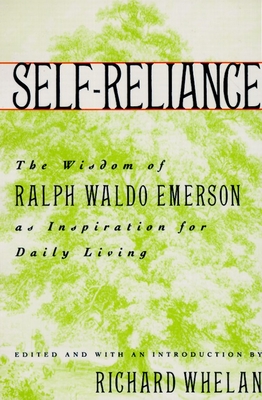

For a good portion of my adult life, I’ve turned to Ralph Waldo Emerson, the great nineteenth century American transcendentalist writer, whenever my vision gets cluttered . When I wonder about the world and my place in it, his writings have a restorative effect on me. I own this wonderful, worn paperback book, Self Reliance: The Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson as Inspiration for Daily Living. It’s a condensed version of Emerson’s essays edited by Richard Whelan. My copy is almost twenty years old, the cover worn to a sun-bleached smoothness, the pages gently yellowed. A small part of me is ashamed that I turn to this much-abridged, ‘best-of’ version of Emerson’s work rather than reading the whole text, but the Whelan book has been with me since I was a young man more prone to short cuts and self-help aisles in the bookstore. I’ve underlined and starred dozens of the pages. In many ways, the book has been a trusted companion for most of my adulthood.

For a good portion of my adult life, I’ve turned to Ralph Waldo Emerson, the great nineteenth century American transcendentalist writer, whenever my vision gets cluttered . When I wonder about the world and my place in it, his writings have a restorative effect on me. I own this wonderful, worn paperback book, Self Reliance: The Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson as Inspiration for Daily Living. It’s a condensed version of Emerson’s essays edited by Richard Whelan. My copy is almost twenty years old, the cover worn to a sun-bleached smoothness, the pages gently yellowed. A small part of me is ashamed that I turn to this much-abridged, ‘best-of’ version of Emerson’s work rather than reading the whole text, but the Whelan book has been with me since I was a young man more prone to short cuts and self-help aisles in the bookstore. I’ve underlined and starred dozens of the pages. In many ways, the book has been a trusted companion for most of my adulthood.

The voices which we hear in solitude grow faint and inaudible as we enter the world. Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members, Emerson writes, always speaking directly to my heart, always illuminating the dark corners of my introverted being. He may ignore the danger of his philosophy, that tendency toward self-righteous solitude and mild paranoia that self-reliance can engender, but he reassures me. This world can be a transcendent place.

Emerson first came to me during a tumultuous time. I had left the military, could no longer fly airplanes, and had no idea what I was going to do with my life. My family was still reeling from my parents’ recent divorce and the death of my grandparents. All of the foundational things of my youth—family, career, belief systems—had been tossed upside down in short order, as if some malevolent force had entered my life at twenty-three and snow-globed it, shaking it good and hard, until I couldn’t see through the glass. It was a confusing and terrifying time. Damned near every part of life felt like a blind spot then. It’s not surprising that I trolled the self-help aisles, dabbled in Zen, or discovered Emerson.

In practical application, it’s nearly impossible to heed Emerson’s transcendent advice even some of the time, to live life with the reverence it deserves, but I always return to this book when the going gets tough.

I’ve become acutely aware of how much I don’t know, of the gaping holes in my intellect. To believe your own thought, to believe what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men—that is genius. How do you trust yourself when you realize the full extent of your laziness and of squandered years? Perhaps these are my blind spots, the lacunae of my ignorance, the vast chasms of books I haven’t read, experiences I haven’t lived, lovers unloved and friendships undiscovered or left to rot through neglect. How much of my life involves compensating for a lack of vision, ignoring my blind spots and polishing the weaknesses so that those spots seem less obvious to the people around me? Too much, I suspect.

Or maybe what’s not readily visible isn’t a menace but an invitation. Perhaps blind spots aren’t dangers, not the lurking monsters hell-bent on running me off the road, but moments of recognition of the power and beauty of life, the spiritual laws, history, friendship, intellect, character, experience and nature, all with the intention of restoring me to the road. There is a difference between one and another hour of life in their authority and subsequent effect. Our faith comes in moments; our vice is habitual. Yet is there a depth in those brief moments which constrains us to ascribe more reality to them than to all other experience. Maybe BLIS would help me take stock in those faith moments. Maybe blind spots are necessary, if only to throw a contrasting dye into the blandness of the mundane. Emerson’s writings have always operated that way for me, infusing color into the darkness, a swirl of orange light reminding me to notice the simple majesty of a scrub jay squawking as the sun rises over the mountains.

There is a switch on my dashboard to disable the BLIS. Emerson might have thought that we all have internalized blind spot detection systems but that we habitually ignore them, or have turned them off. A man should learn to detect and watch that gleam of light which flashes across his mind from within, more than the luster of the firmament of bards and sages. Yet he dismisses without notice his thought, because it is his. But how to see those gleams of light, that’s the question? I certainly couldn’t detect much value in my life at twenty-three. Most days, I put my head down and tried not to think too much about the blind spots. It might not have changed much in the intervening years, but then again, maybe it has.

I wonder what old Ralph would think of this gadget in my car. Would he admire its efficiency, or would he scoff at it, yet another automated tool in our already over-mechanized lives, as he likely would deride our dependence on internal combustion engines, highways, and the wars we wage to maintain a steady supply of fuel? The soul is no traveler, he writes. The wise man stays at home. This from a man who travelled all over Europe, at a time when his twenty-mile trip from Concord to Boston took the better part of four hours. Emerson knew that about the restlessness of the soul. He saw the Pyramids, the Alps, the Grand Canal in Venice. We are nomadic creatures by nature. Today, we leap great chasms of time and distance via the internet and television, we zip across oceans in the time it took Emerson to deliver a lecture at Harvard and get home for dinner. We watch wars and tsunamis unfold in real-time, communicate instantly with people all the way across the globe. Yet I can’t escape myself, no matter how fast I drive, how high I fly or how far I travel. Maybe he’d think that a blind spot detector is just one more way we’ve grown adept at letting technology do the work for us, at conveniencing the self out-of-the-way.

Still it’s hard to live in this world without such things. In spite of whatever simple-life tendencies I admire in Amish buggies or Trappist monasteries, I either embrace BLIS systems, E-readers, i-Pods and cyberspace, or perish in the modern world. No Luddites Allowed, the sign above the door says. Emerson knew this in his own way. It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude. Escape is not a solution to the problems of the world, but rather a symptom of their prevalence. Retreating from the world wouldn’t really get rid of my blind spots in a meaningful way, anymore than pulling to the side road does. You eliminate the immediate danger, but hardly arrive at the destination. But how to find that perfect sweetness, how to leave behind the blind spots of Being when the crowd keeps getting louder, larger and less interested in nineteenth century philosophers?

Even with BLIS in my car, I still turn my head to verify the light’s accuracy—a quick glance, more out of habit than concern. I notice that the duration and diligence of my glance decreases with each passing day. My reliance on that orange light grows. This may not be a good thing.

There is a time in every man’s education when he arrives at the conviction that envy is ignorance; that imitation is suicide; that he must take himself for better, for worse, as his portion; that though the universe is full of good, no kernel of nourishing corn can come to him but through his toil bestowed on that plot of ground which is given him to till. Till my own soil, Emerson tells me. Stay at home, no matter how fallow the land. But envy and imitation are the lifeblood of a commodity culture, seeping through every capillary of mass media, niche publishing and contemporary American dreaming. Who reads Emerson anymore? Who the hell cares about the ruminations of some quiet, contemplative stay-at-home dad with two kids, a hot temper, a second-rate intellect and a light green Volvo XC-90 in the driveway?

And what about all these damned blind spots?

-Richard Farrell

Great essay, Rich. I’ll read what your “second rate” intellect is at work on, anytime. This got me thinking about my own blind spots – how many I know I have, and how many more I surely have that I just don’t know about yet. I guess it can be fun finding a blind spot, even if in the finding more pop up. Which they seem to, always. It’s kind of like the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, when Mickey chops the broom and it becomes two and then four and so on. Only not as violent. Or animated.

“It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.”

Man, to have a perfect sweetness while going after those blind spots (brooms)? Man, hopefully someday I can be there. Let me know if you figure it out. What to do about those damn blind spots indeed.

Thanks for reading, Ross. The more I think about blind spots, the more elusive they become!

Nice Rich. I’ve been admiring how you tied together diverse threads, how they play off of and inform each other.

I especially like this imagery:

“I’ve grown quite fond of BLIS, quite accustomed to the orange glow, especially in the dizzying commutes on Southern California freeways. It’s a helpful aid. A cheat, if you will, a machine doing the vigilant work that the driver is supposed to do. With only a quick glance at the side mirrors, my peripheral vision catches the orange light and I know that something lurks in those hidden spaces.”

Grazie, Natasha!

Thanks for this thought-provoking essay Rich.

I think back to my driving instructor – it was like magic when he demonstrated the blind spot to me. I like what you’ve done with it.

Thanks for reading, Lynne!

Spot on, Rich. Truly.