A record snowstorm buried eastern Pennsylvania in December of 2010. While the snow piled up, Ian Thomas, on break from the University of Missouri, slipped back into familiar routines. He slept late, hung out with high school friends, watched football games with his father and helped decorate the Christmas tree with his mother. Ian passed the days scribbling in a notebook. Flopped on a couch as the Philadelphia suburbs disappeared under almost two-feet of fresh powder, Ian wrote out the draft of a short story. He titled this story “The Freak Circuit” and, for the first time, he expressed a desire to seek publication for his work.

This short story also was the last one he ever wrote. Less than two months later, Ian Thomas was dead.

“The Freak Circuit” is a 12-page story about an exceptionally talented high school basketball player named Tim. Though a highly touted recruit, Tim houses a debilitating secret: he is a closeted gay teen on the verge of entering the world of high power, big money athletics, where few (if any) openly gay male athletes exist. Told in one nearly breathless paragraph, with images that tumble and cascade at a breakneck pace, so much of the story looks outward, gazing into distant campuses, into a coming athletic career that seems certain for success and destined for heartbreak. Tim dribbles and shoots, imagining World War II battles and the skinny red-haired boy he once kissed at a frat party in Tennessee. Everything hinges on possibilities. Where will he go to school? Which coach will he play for? How will he hide his homosexuality? The story pivots like a point guard, calculating, choosing. There are doors to open, opportunities to explore, peril at every turn. Precariously balanced between hope and despair, Tim is at once blessed and cursed:

Tim is outside again, thinking about the Battle of Iwo Jima while pounding a deep orange Wilson basketball into the backyard patio’s cracked, uneven stone surface, bounce, bounce, concentrating deeply, thinking of February 1945 while calculating the days until the ball will become smoothed out and useless, its thousands of tiny hills flattened by four hours a day, bounce, six days a week, by gravity and by patio. He’s under strict and emphatic direction from his high school head coach, an aging, wool-haired basketball lifer who can smell, in one’s sweat, the difference between the assigned four hours of home practice and three and a half. Tim thinks about Tennessee and closes his eyes.

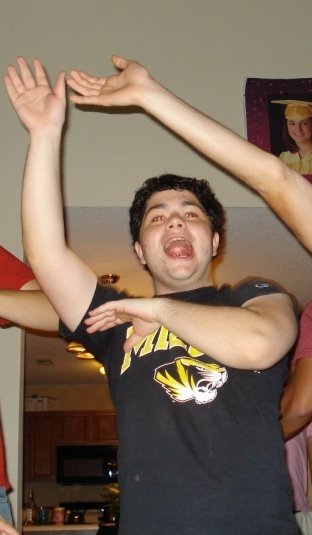

In January, Ian returned to school and started sending out “The Freak Circuit.” He submitted to twenty magazines. Ian’s roommate, Dan Cornfield, tells me that most days Ian was a typical college student. He dressed up in black and gold and went to basketball games at the Mizzou Arena. He attended class, went to parties, and played video games at home.

“He never did homework,” Dan says. “If I was trying to study, he’d pester me until I gave in and stopped.”

Ian also suffered from depression and could spiral into darkness. Locked in his room, he would skip class and go days without eating. His friends and family knew about his about his struggles with rage and sadness. And his pain would have been doubly saturated at college, where all around the perception was that life thrummed along. Ian didn’t resemble the tall, lean and muscular ideal that our campus culture demands from its youth. At less than five-and-a-half feet tall and stocky in stature, Ian wore his hair thick and curly, adding bulk and height to his frame. His face was round and his eyes were dark. More often than not, he wore an Eagles’ jersey or a Phillies’ cap. He survived on his wit and a biting sense of humor. Most times, it was enough to keep him going. But when he slid into the darkness, the isolation must have been debilitating, extreme, feeding on itself.

Ian must have felt a part of his own freak circuit.

On January 26th 2011, less than three weeks before his death, Ian submitted the “The Freak Circuit” to upstreet magazine. Most national literary magazines receive hundreds if not thousands of submissions during a cycle. The odds of a story rising through the slush pile and being published are astronomically low. Vivian Dorsel’s magazine is no exception. For its seventh issue, upstreet received 1,119 fiction submissions. From this lot, they would publish only six stories. This means that a submitted story stood far less than a one out of a hundred chance of being accepted. Like many magazines, upstreet selects only the very best stories from its submissions pile. Like many magazines, upstreet is a non-profit. The recompense for the successful author, chosen against these astronomical odds, is two free copies of the magazine. (I should point out that I am the Non-Fiction Editor at upstreet, but I did not play any part in the editorial decisions with fiction submissions. I first read “The Freak Circuit” in October of 2011.)

At upstreet, “The Freak Circuit” moved quickly up through the slush pile. On February 2nd, a fiction reader forwarded the story to the fiction editor with a positive recommendation. On February 9th, the fiction editor read the story and also recommended it. She sent the story back to Dorsel for a final decision. Five days before his death, Ian’s short story was sitting in the front of the magazine’s editor and publisher, awaiting a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ vote for publication.

Maureen Stanton, Ian’s writing professor and mentor at Missouri, tells me that Ian was considering graduate school; she says that he was eager to begin sending work out, even ready to start receiving rejection letters. She describes Ian as one of the most gifted students she’s ever taught. “I’d seen him that Thursday before he died,” Stanton says. “He was excited about summer writing workshops and applying to MFA programs. He’d stopped by my office to pick up a copy of a magazine I’d saved for him with a list of the best workshops and we chatted for about 20 minutes. I wish I’d had more time to talk to him.”

At times, Stanton’s praise for Ian might be misconstrued as eulogistic. The glowing terms she uses—words like visionary, charming, poetic, extraordinary—outshine the complex reality of any twenty-one-year-old undergrad with a non-existent publication record and middling grades. But the more we talk, the more Stanton’s sincerity seems unforced.

“His voice was lyrical and poetic,” Stanton tells me. “He had an extraordinary command of vocabulary, the rhythm of sentences. He could explode ideas—break them open and challenge.”

Stanton also talks candidly about Ian’s struggles with depression, his self-centeredness, his sensitivity to criticism. A bad workshop could send him spiraling back into dark places. In the privacy of Stanton’s office, he would be harsh on other student writing. He could be cavalier in class, opinionated, hard to manage.

He thinks about Henry VIII very quickly before thinking about Ray Allen and How to Line Up the Perfect Three Pointer, The Pro Way©, the way Ray taught him at the elite camp in Boston, bounce, he spreads his feet about a foot apart and lines them up directly parallel to his shoulders like he’s supposed to, but he remembers how, at that same camp, he missed fifteen of twenty three-pointers the Ray Allen Pro Way© (and failed to hit the rim on seven), so he squats lower than he should and jumps higher than he should with his feet where they shouldn’t be, all pressed together with the right side of his left shoe’s toe resting on the toe of the left and the ball sails in.

At 6:45 in the morning on Valentine’s Day, the phone rang in the suburban Philadelphia home of Linda and John Thomas. Linda answered. On the other end of the phone, Ian’s friend, Chris, told Linda that her son had been rushed to an emergency room in Columbia. Ian was still alive, but he was intubated and had already coded once. For a while, in the stillness of their kitchen, Ian’s parents held out hope that their son might pull through. The next phone call obliterated that hope.

So much of the future is assumptive. We assume the sun will rise tomorrow, that our children will grow up and go to college, that hard work will pay off. But often, those assumptions rest upon the frailest of armatures.

During the many times I speak with Ian’s father, I never directly ask him how Ian died. John Thomas refers his son’s death as an accident. John also candidly talks about his son’s depression.

John flew to Missouri on Wednesday, February 17th, two days after Ian’s death. He talks about the open friendliness of Midwesterners. He speaks of this quality as if it were due to some fact of geography, and not by the grim reality that John had gone there to retrieve his son’s body. Ian’s mother, too grief-stricken to consider travelling, stayed home in Pennsylvania.

Ian’s roommate, Dan, describes the days following Ian’s death:

“Our apartment was just full of people,” Dan says. “My mom drove down from Chicago to be with us. My brother was sleeping on the couch. People just kept showing up. We had more brownies and cookies than we could eat.”

A lingering note of innocence tinges Dan’s voice. The shock, the disbelief, the sheer magnitude of losing a close friend at twenty-one is still settling in almost a year after the fact. He tells me that after a few days, his roommates cleared everyone out of their apartment. They wanted to be alone when Ian’s dad arrived on Wednesday.

“I didn’t know what to say,” Dan says. “None of us did. There were these long pauses. The whole time, Mr. Thomas tried to make us feel comfortable.”

John met Ian’s college friends for the first time on that trip. He would also meet Maureen Stanton. People gathered, cried, told stories, and shared laughs. On Friday, John packed up the last of his son’s belongings. He collected Ian’s clothes, books and notebooks. He packed up his laptop and, for the very last time, stripped his son’s bed. Then John flew back home with Ian.

He thinks of the peculiar way his stomach burned and twisted and ached and how he nearly soiled his compression underwear under his black mesh shorts when that huge black center at the Mississippi elite camp looked Tim in the eye and said you know, white boy, you shoot like a fucking faggot, how he almost burst into powder at that moment, how he almost booked his own last minute flight home, back to the safe dull colorless center of Pennsylvania, how he nearly collected every basketball and every piece of equipment he owned and every signed jersey and every letter of interest from every big-time American basketball university and every framed photo of NBA stars and neatly piled all of it in the middle of the cracked stone patio and burned it, doused the spot in lighter fluid and burned it to fucking hell. Bounce. He thinks about the eerie exhibitionism of this whole freak circuit, his leisurely (borderline immoral) little traipse from university to university, how they can all see through him (probably), how his coaches and maybe even his own father are carving what Tim thought Tim was into a 21st– century kind of bearded lady.

On February 23rd, nine days after Ian’s death, upstreet’s editor, Vivian Dorsel, read “The Freak Circuit” and decided to take it for publication. She sent a congratulatory email to Ian.

Dorsel then waited over two weeks for Ian’s reply, which never came. On March 7th she sent another email, but there was still no response. Two days later she did a Google search and found an Ian Thomas on the University of Missouri website. Ian was listed as an English major, a senior, a staff writer on the student newspaper. She found his university email address and contacted him yet again: “If you are the Ian Thomas who submitted a story to upstreet in January,” Dorsel wrote, “please get in touch with me. I have sent you two messages and you haven’t responded.”

Later that same day, Dorsel called the university’s English department. They passed her on to an undergraduate advisor who provided Ian’s home phone number and address in Pennsylvania. No one at the university told her that Ian Thomas was dead.

Dorsel’s pursuit of this story seems paradoxically single-minded. Why did she care so much? Aren’t editors, with a thousand stories to wade through, cold and unyielding? Editors read until the first mistake, or so goes the old adage. Dorsel describes her interest in “The Freak Circuit” this way:

What struck me about “The Freak Circuit” was the voice, which I found intense, compelling, and consistent throughout. William Faulkner, in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, spoke of “…the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.” I think Ian’s story is an example of what Faulkner was talking about, and it is a very sophisticated and well written piece of work for someone so young; I also thought the ending was perfect, which is rare. I was so convinced it was right for upstreet that I was not willing to give up until I had exhausted every possibility. When I was laying out number seven, I decided to lead the issue with “The Freak Circuit.” It just seemed like the right thing to do.

On the evening of March 9th, Dorsel called Ian’s parents at their home. John Thomas answered and informed her that Ian was dead. He also told her that he wanted upstreet to go ahead and publish the story. It would mean a great deal, he said, to see his son’s story in print.

Over the course of several months, Johan Thomas and I exchange a flurry of emails. I also talk with John Thomas twice on the phone. The first time is on Halloween, eight months after burying his son. It is a gray Monday in Melrose Park, Pennsylvania, where John and his wife, Linda, live. The Philadelphia suburb has just received its first dusting of snow, a full six weeks before winter officially begins. When John and I finish talking, I will drive beneath San Diego’s seventy-five degree blue skies to pick up my kids at their school. We will come home, have an early dinner, and go out trick-or-treating.

John puffs on a cigarette as we speak. He and I are, for all intents and purposes, strangers. In the background, I hear voices from a television. I picture a living room, a recliner, a smoldering ashtray. We talk for almost two hours.

“He was born a writer,” John says with a father’s recalcitrant pride. “He wanted to write since he was three.”

John is a youth crisis counselor, but hasn’t worked since the summer, when his hospital was all but destroyed by Hurricane Irene. Repairs at the hospital are on-going, but he doesn’t know when he is expected back at work.

“Sometimes I think it would have been easier,” John says, “if we’d had more kids. But who knows?”

It’s difficult not to wonder about the suffering imposed on people like John Thomas and his wife, the Job-like quality of their despair and the bare-knuckled perseverance in the face of it.

John is also a craftsman. He makes stained glass windows and sells them at trade shows and craft fairs. Only in the last few days, more than eight months after his son’s death, has John returned to his studio and begun working again.

“It’s a destructive art,” John says of working in stained glass. “You’re always cutting and breaking and splintering things. You’re always covered in shards of glass.”

We talk about simple things, about sports, the Mummer’s parade in Philly, cheese steaks, the Phillies and the Eagles. He tells me about Ian’s decision to switch majors at Missouri, from journalism to creative writing. John dallies in the banal before stepping over into the abysmal horror of what has happened.

“Everything gets filtered through it,” he says. “But what can you do?”

The University of Missouri lost eleven students during the 2010-2011 academic year. This number seems staggeringly high. What was happening in Columbia to cause so many young people to die? This is only one of the many questions which will never be answered for me. When talking to John Thomas, I realize how little I will ever know of Ian, or of the particular pain that his death has brought.

“There is no name for this,” John says. “For this kind of grief, when a parent loses a child.”

Thinking too much too closely, holding it all too close to his body. He thinks of Tennessee, the funny long shape of it on the huge map in his room, the boy who kissed him in the orange. Tim takes two more steps backwards and launches his deep orange ball towards the black rim with that shot, that unique hurricane of elbows and limbs mashed together, and watches it slip through the net without making a sound, without even a little swish.

John and I speak again in January. He tells me that the holidays were brutal, that the time since Thanksgiving has been especially grim. He and his wife didn’t celebrate. They didn’t even put up a Christmas tree.

He tells me that Ian never had a curfew, never had a bedtime. John is trying to paint a picture for me, a picture in words and anecdotes, of his son. He tries his best to make the image real.

Again, the conversation swings wildly, from seemingly normal chit chat to raw grief. John switches in and out of the most emotional topics quickly. The conversation turns back and forth, from stories of Ian’s struggles with math assignments to his lingering battle with depression. John tells me about his son’s eagerness to receive rejection letters.

“He figured that it was part of the job. That getting rejected would make him a real writer. He didn’t want to be a writer,” John says, stressing the indefinite article. “He wanted to be the writer.”

John also tells me that Ian ripped out “The Freak Circuit” in no time. Only a year earlier, Ian was home over winter break, lounging around on the couch as the snow fell, writing in a notebook.

“He just was playing around with it,” he says. “He didn’t even write fiction most of the time. Who knew it would end up getting published?”

John concludes our conversation by asking me to throw a ball with my son, a mundane acts which suddenly explodes with significance.

“I miss him,” John says. “He was a good kid.”

At Ian’s elementary school, his parents have established a writing award in their son’s name. Etched into the plaque for the award are the famous words of Maya Angelou: “The bird doesn’t sing because it has an answer, the bird sings because it has a song.”

Perhaps those who knew Ian can seek and find solace in this, in the gesture of young writers being touched by Ian’s memory and in the words of a poet who speaks to the ineffable mystery of life and death. Angelou also wrote, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside of you.”

At least Ian’s story gets told. “The Freak Circuit” defies the odds. This speaks to Ian’s abilities and his devotion to writing. It also speaks to the dedication of people like Dorsel and Stanton who championed the work of a young writer still taking his tentative first steps.

But these conclusions are hollow and arc toward sentimentality. I have no doubt that John Thomas, Dan Cornfield and Maureen Stanton and everyone else who knew Ian would happily trade every one of his words, published and unpublished, for a few more days with him.

If I find any possible conclusion, it might be in the twenty-five pages of “The Wellbutrin Diaries.” This long essay, written by Ian the autumn before he died, traces a season in the life of Ian Thomas. It was written in Stanton’s non-fiction seminar and it is Stanton who sends it to me. In places angry, in places broken and shattered, in places sublime, the diary is an intimate look into the mind of a young writer whose talent and passion seemed to grow the more I searched.

If there is to be an epitaph for Ian Thomas, it must be through his words. If there is to be even the hint of an answer for his family and friends, it must gesture out from that darkness, the darkness of depression, from the struggle of a young man trying to create something beautiful. Ian’s words once announced a certain talent, a raw voice which spoke with clarity and wisdom, cut down long before that voice could sing. If there is to be a conclusion, it must belong to Ian:

One day, though, it will happen. Simplicity will win, or at least tie. I will write—and think—like my mind is at peace. Shit, maybe even it will be. I can see it manifested and it looks like this: I’m on a boat, in the middle of a pond, in the middle of the night. The water is still, and the moon is casting an ivory glow over me as I row, as I maneuver into silence. I see it like it’s in front of me right now. My thoughts will be short, and they will be happy, and I know, for however long the ride lasts, I’m in the right place, on the right planet, in the center of the right universe. For good. I’ll make my own kind of comfort. And I’ll think (no, I’ll know). It’s all just that easy.

— Richard Farrell

Richard Farrell earned my B.S. in History at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis and an M.F.A. at Vermont College of Fine Arts. He is a Senior Editor at Numéro Cinq and the Non-Fiction Editor at upstreet. In 2011, his essay “Accidental Pugilism” was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. His work has appeared in Hunger Mountain, Numéro Cinq, and A Year In Ink. He is a full-time freelance writer, editor and a faculty member at the River Pretty Writers Workshop in Tecumseh, MO. He lives in San Diego, CA with his wife and two children.