/

A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by statesmen and philosophers and divines. If you would be a man, speak today what you think today in words as hard as cannon-balls, and tomorrow speak what tomorrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict everything you said today.

-Ralph Waldo Emerson

/

My car has a factory-installed blind spot detector, a system that the manufacturer, Volvo, calls BLIS, or Blind Spot Illumination System. (The actual device, fortunately, works better than the acronym.) It consists of a camera mounted below the mirror that is wired to a tiny orange light inside the car. The dime-sized, triangular light illuminates when another vehicle is moving somewhere in my car’s blind spot. I’ve grown quite fond of BLIS, quite accustomed to the orange glow, especially in the dizzying commutes on Southern California freeways. It’s a helpful aid. A cheat, if you will, a machine doing the vigilant work that the driver is supposed to do. With only a quick glance at the side mirrors, my peripheral vision catches the orange light and I know that something lurks in those hidden spaces.

I wonder what it would be like to install an automated blind spot detector on myself, BLIS for the soul, illuminating the parts I fail to see. What would such a device show? Would it light up when my hot temper flares, or when I’m impatient with my kids or insincere with my wife? Perhaps it would reveal buried things about my desires, expose my snap judgments toward other people, or render visible my hidden fears and anxieties. How embarrassing it would be to have at a party, in a room full of strangers, glowing as a boorish lawyer droned on about his wonderful job, or lighting up like Rudolph’s nose on Christmas Eve as a pretty woman crossed the room. But if I’m already aware of these shortcomings, even in brief, then maybe that’s not what this blind spot detector would do at all. Maybe it would only flash on when least expected, revealing aspects of myself I can’t see, or don’t want to. How often would that little orange light glow?

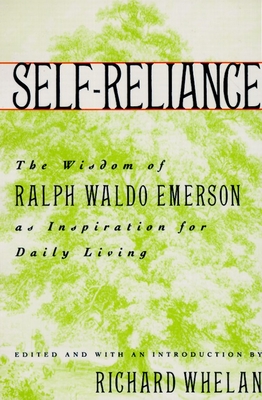

For a good portion of my adult life, I’ve turned to Ralph Waldo Emerson, the great nineteenth century American transcendentalist writer, whenever my vision gets cluttered . When I wonder about the world and my place in it, his writings have a restorative effect on me. I own this wonderful, worn paperback book, Self Reliance: The Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson as Inspiration for Daily Living. It’s a condensed version of Emerson’s essays edited by Richard Whelan. My copy is almost twenty years old, the cover worn to a sun-bleached smoothness, the pages gently yellowed. A small part of me is ashamed that I turn to this much-abridged, ‘best-of’ version of Emerson’s work rather than reading the whole text, but the Whelan book has been with me since I was a young man more prone to short cuts and self-help aisles in the bookstore. I’ve underlined and starred dozens of the pages. In many ways, the book has been a trusted companion for most of my adulthood.

For a good portion of my adult life, I’ve turned to Ralph Waldo Emerson, the great nineteenth century American transcendentalist writer, whenever my vision gets cluttered . When I wonder about the world and my place in it, his writings have a restorative effect on me. I own this wonderful, worn paperback book, Self Reliance: The Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson as Inspiration for Daily Living. It’s a condensed version of Emerson’s essays edited by Richard Whelan. My copy is almost twenty years old, the cover worn to a sun-bleached smoothness, the pages gently yellowed. A small part of me is ashamed that I turn to this much-abridged, ‘best-of’ version of Emerson’s work rather than reading the whole text, but the Whelan book has been with me since I was a young man more prone to short cuts and self-help aisles in the bookstore. I’ve underlined and starred dozens of the pages. In many ways, the book has been a trusted companion for most of my adulthood.

The voices which we hear in solitude grow faint and inaudible as we enter the world. Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members, Emerson writes, always speaking directly to my heart, always illuminating the dark corners of my introverted being. He may ignore the danger of his philosophy, that tendency toward self-righteous solitude and mild paranoia that self-reliance can engender, but he reassures me. This world can be a transcendent place.