Here’s a very smart, ever so pyrotechnical essay on my novel The Life and Times of Captain N by Cheryl Cowdy who teaches Canadian literature and children’s literature at York University in Toronto. The essay is an inspiration on several levels, not the least of which is Cheryl’s critical intuition that she could take the book A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari as a parallel text and let the two books illuminate one another. The result is an essay replete with brilliant reflections and intuitive leaps that says something about novels, art, the self, history and, um, the French penchant for complicated metaphors.

There is a story that goes with this essay. In 1999 the editors of Henry Street, a scholarly magazine published at Dalhousie University, got in touch with me. They had an exciting essay about Captain N, and they wanted me to enter into a dialogue by email with the author, which dialogue they would publish in conjunction with the essay. This dialogue was a feature they had just invented called “Lines of Flight.” The first attempt hadn’t worked so well; the author got testy with the graduate student and the experience had not been sunny. The editors wanted to be sure I wasn’t going to be mean. I told them I am not a mean person (um, despite my students calling me the Shredder). They sent me the essay (which delighted me) and put me in touch with Cheryl. And then we spent a couple of lovely months shooting emails (once in a while, slightly lubricated) back and forth on novels, rhizomes, French theory, and life (camping trips and thunder storms impinged). We were strangers, but well disposed, and we were supposed to talk. I think we forgot, at times, that the result was going to be published. It was a sweet thing: two strangers, a bit on the spot, tentatively feeling each other out and then discovering moments of intellectual play. And, well, a dozen years later, we’re still friends.

Here is Cheryl’s self-bio note, too charming to rewrite:

I really hate writing biographies; can we just say I teach Canadian and children’s literature at York [University in Toronto]? My current obsessions have to do with play and ritual, but I’m still fascinated by the suburbs (I used a quote from “The Indonesian Client” in my dissertation on the burbs in Canned lit, did I tell you that?). Then can we tell the story of our correspondence over my Deleuzian reading of Capt N? It’s a good story, that one.

This essay and the accompanying “Lines of Flight” interchange were originally published in Henry Street, 8:1, 1999.

dg

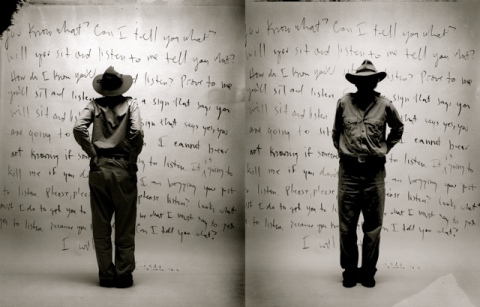

Original Alfred A. Knopf edition.

Original Alfred A. Knopf edition.

.

Becoming is an antimemory. Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus 294

I am against the future. Hendrick “Dutch Henry” Nellis, The Scourge of Schoharie, 1779[1]

.

How does one write a book about Indians? This is one of Oskar Nellis’s dilemmas in The Life and Times of Captain N. Douglas Glover’s dilemma: How does one write a book about history? My dilemma: How does one write an academic essay about The Life and Times of Captain N. and A Thousand Plateaus, two texts that seek liberation from linear structures of thought? And does the problem of writing about Indians and History become part of my dilemma also?

But when one writes, the only question is which other machine the literary machine can be plugged into, must be plugged into in order to work (Deleuze and Guattari 4).

And,

Literature is an assemblage (4).

Can I plug the Glover machine into the Deleuzo-Guattarian machine? What kind of assemblage will this make? Will it work? (“Don’t ask questions you can’t answer”—My advice to undergraduates on writing research essays. Here I am—breaking the rules. Sometimes there are only questions . . . leading to more questions . . .)

Oskar thinks he could write a whole book, and there would be nothing in it but questions (Glover 24).

In many ways, A Thousand Plateaus seems antithetical to books about History and Indians. “Becoming is an antimemory.” Does this mean Deleuze and Guattari are against the past? Hendrick Nellis, or Captain N., professes to be “against the future.” Is this a contradiction, or are they both simply for the present?

“Unlike history,” say Deleuze and Guattari, “becoming cannot be conceptualized in terms of past and future. Becoming-revolutionary remains indifferent to questions of a future and a past of the revolution” (292).

The present then. But how shall I plug them all in together? As Deleuze and Guattari advise,

Writing has nothing to do with signifying. It has to do with surveying, mapping, even realms that are yet to come (4-5).

And,

[W]rite at n – 1 dimensions. A system of this kind could be called a rhizome (6).

A rhizome ceaselessly establishes connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences, and social struggles (7).

There are no points or positions in a rhizome, such as those found in a structure, tree, or root. There are only lines (8).[2]

Write rhizomatically. But, I protest, there must be an argument! There must be a thesis!

The majoritarian argument, then: According to Oskar Nellis, one of the storytellers and protagonists of Douglas Glover’s novel, The Life and Times of Captain N., “Everything is a sign of everything else.” It is a state of being that causes him to feel “lost in a circular whirl of interchangeability based on masks” (52). This state of being, or of interchangeability, might more aptly be called a Deleuzo-Guattarian “state of becoming.” Like Deleuze and Guattari’s conceptualization of identity in terms of “becomings,” Glover’s historical novel articulates a notion of cultural and national identity that privileges indiscernibility, symbolized by the Iroquoian whirlwind masks that figure so prominently in the novel. This has a direct bearing on the question of History and Indians, for it is by reading Oskar’s book about Indians within the text of The Life and Times of Captain N. that he and his readers become-Indians (which is a fine way of saying we become-everybody/everything).

The minoritarian argument . . . But wait, Deleuze and Guattari object . . . “Flat multiplicities of n dimensions are asignifying and asubjective. They are designated by indefinite articles, or rather by partitives (some couchgrass, some of a rhizome . . .)” (9).

Fine then . . . some minoritarian arguments: Plug The Life and Times of Captain N. and A Thousand Plateaus into each other. Make an assemblage. “Collective assemblages of enunciation function directly within machinic assemblages” (7). Make a machine, a BwO (a Body without Organs, a Book without Origins). Create: Lines of Flight. Planes of Consistency. Connections: “and . . . and . . . and ”(25).[3] “[A] line of becoming has neither beginning nor end, departure nor arrival, origin nor destination” (293). A Becoming-Glover of Deleuze and Guattari and a Becoming-Deleuze-and-Guattari of Glover. “Each of these becomings brings about the deterritorialization of one term and the reterritorialization of the other” (10). Is it true?

As Brian Massumi states in his foreword to A Thousand Plateaus, “The question is not: is it true? But: does it work? What new thoughts does it make it possible to think? What new emotions does it make it possible to feel? What new sensations and perceptions does it open in the body?” (Massumi xv). Will it work then?

I’m not sure, but the connections are there. Like Deleuze and Guattari, Glover writes and theorizes the middle, the inbetween space elided by dualism machines. Binary machines that separate being and nonbeing, self and other, “God and reason,” as well as America (“the rhizomatic West,” for Deleuze and Guattari, “with its Indians without ancestry, its ever-receding limit, its shifting and displaced frontiers” [19]) and “the old country” (Oskar “wondering which old country”—suggesting it doesn’t really matter [112]). Many of the characters in The Life and Times of Captain N. feel they are, like Nellis himself, “between peoples” (19). For Deleuze and Guattari, “the only way to get outside the dualisms is to be-between, to pass between, the intermezzo . . .” (277).

“Are you ready to write?” asks Oskar (32). .

.

Becomings. Becoming-masks.

A becoming is always in the middle; one can only get it by the middle. A becoming is neither one nor two, nor the relation between the two; it is the in-between, the border or line of flight or descent running perpendicular to both. Deleuze and Guattari 293.

The Truth is a Mask & its Signe is Division. It is Nought but what lies between Things. It whirls. Yet I believe that to know It is a kind of Madness & a joyful Relief. Glover 99

.

In A Thousand Plateaus, the concept of becoming is described as “a zone of proximity and indiscernibility, a no-man’s-land” (293), as it were, that is itself the in-between of being and non-being. When they speak of becoming-girl, becoming-woman, or becoming-animal, Deleuze and Guattari are not advocating an imitation or identification with the other. Becoming is a notion that they are constantly reinventing, making it difficult to define. However, several of the ways Deleuze and Guattari describe becoming are suited to a comparison with the articulation of identity in The Life and Times of Captain N. Becoming is, as the epigraph to this section explains, an “in-between” zone, which is particularly resonant with Hendrick Nellis’ avowal in the novel that he is “between peoples” (Glover 19). Deleuze and Guattari explain that becoming is to extract particles between which one establishes the relations of movement and rest, speed and slowness that are closest to what one is becoming, and through which one becomes. This is the sense in which becoming is a process of desire. (272)

Becoming is a “process of desire” through which one becomes-other, abandoning one’s major identity with “state[s] of domination” to be “deterritorialized,” to communicate with the other (291). As Elizabeth Grosz explains, becomings “always involve a substantial remaking of the subject, a major risk to the subject’s integration and social functioning” (174).

In The Life and Times of Captain N., being “between peoples” means being a split subject, risking one’s subjective integrity, as well as one’s social, national, or cultural identity. There are times when Hendrick Nellis’ philosophy reads like a section from A Thousand Plateaus. When he reflects on the attitudes of those people who cross cultures with ease, Nellis echoes Deleuze and Guattari’s emphasis on becoming as a no-man’s-land, and as “a process of desire”:

In the no-man’s-land between peoples, languages, and customs, there is no custom, only naked desire and misunderstanding. It is a childlike state, full of violent experiment—when I think of this I am reminded of the mask of the Whirlwind. Once they have gone there, few ever return. (80-81)

For the characters in The Life and Times of Captain N., Iroquoian masks are a sign of the often chaotic and confusing process of becoming-other. It is, as Nellis observes, a violent state, potentially leading to “misunderstanding,” a risk to the stability of one’s identity. Yet being-between is also the only state or process that allows one to enter into a relationship of mutuality with the other, to become-everybody/everything, to be redeemed.

By “becoming-masks” the characters of Life and Times lose all sense of stable national, cultural or gendered identities. The Whirlwind mask, also called the mask of the Split-face god conveys this most effectively. Ethnologist William N. Fenton translates the name of the mask as “He Whose Body is Riven in Twain.” He explains that “his body is half human and half supernatural; hence his face is divided between deep red and pure black, symbolizing the east and the west, and he is free to wander at large even among the people” (Fenton 16). As a being that is between life and death, the Split-face god is particularly suited to signifying becoming as a process of being-between. (In photos he looks quite gleeful about this, as if he knows something we don’t). In the zone of “in-betweenness,” the characters of the novel enter the whirlwind of indiscernibility where identity is turned upside down.

Many of the First Nations characters in the novel embody this state of being-between. The “Black Minqua sorcerer,” Crow, paints his face like the Whirlwind; Hendrick Nellis takes the painting to mean, “he is half-spirit and half-human, half-dead and half-alive,” and hence “a medium for the magical forces of the forest, a messenger from the Land of the Dead” (43). Oskar’s friend, Tom Wopat, who is “half-Savage” according to Oskar (14), is a maker of masks.[4] He is also a “down-fended Boy,” which Oskar tells us is “an ancient custom” of keeping a child thought to be “werrie powerful in Magic” (123). It is a sign of his ability to live “between Worlds” (123). Tom is also able to live in the space between dreams and the real. As a “pawaganak” who appears in the dreams of Mary Hunsacker, Tom is “a manido or person who spoke to the Indians in their sleep” (90). For Oskar, Tom is often the spokesperson for becoming-other as an experience that allows one to be renewed or redeemed. Tom tells him that “we will be made new only when we learn to speak the language we cannot understand” (120). This leads Oskar to wonder if this means “that difference itself is sacred? That my savior is the other, whoever he is?” (120). As one of the characters who are “between peoples” (19), Tom understands that embracing difference enables one to gain new perspectives, to think new thoughts, feel new emotions, and open new sensations in the body.

Mary Hunsacker is one white character who learns to live “between peoples” after she is captured by the Mississauga Indians and adopted by them. Mary’s process of becoming-Indian is inscribed with violence; when Scattering Light, one of the Mississauga, clubs her over the head with his death maul, Mary suffers a headache that is quite literally a splitting headache. She explains that the bruising that results from her injury turns her face into “a mask, which nevertheless seemed strangely familiar to me”(26). Such physical pain is often a sign of the cultural in-betweenness that characters like Mary, Hendrick and Oskar experience. Mary senses that her “mask of pain” hides a person she does not know inside (37), signifying the fluidity of her identity, as well as the potential for discomfort that this risk to one’s subjectivity involves.

As she becomes more comfortable with the Mississauga language and culture, Mary learns the skills of wabeno magic under the tutelage of Wabanooqua. This occurs after a doctor for the King’s Regiment places a silver plate in her head, an operation that almost kills her and therefore increases her sense that she lives between the two worlds of life and death. She describes her new subjectivity as a “strange state between being born and giving birth” (73). Mary’s position enables her to be more accepting of ambivalence and in-betweenness. As she explains,

You could never tell what a thing really was. The world was full of shapeshifters and talking rocks and words that had souls. I myself was both what I was and something more on account of that silver plate in my head, my dream, and my song. (117)

Mary experiences her subjectivity as “something more” than her identity as a white woman colonist.[5] As she later recalls, “The world had turned itself upside down for me. I was an Indian, though pale, and a white woman, though I spoke and walked like an Indian” (125). Mary feels that her ability to live between two worlds makes her “a machine for translation” (141). As such, she functions as a “machine for becoming” for others.[6] For Mary, becoming-Indian is a kind of becoming-minoritarian. As Deleuze and Guattari explain, this is necessary since “only a minority is capable of serving as the active medium of becoming” (291).[7]

In many ways, Hendrick Nellis is the most outspoken advocate of becoming-Indian as a means of redemption. He is also one of the most ambiguous characters in the novel. As Glover remarks, “Nellis isn’t a liberal. He’s no improver. He has already rejected history and the future. He’s a tragic hero, an Old Testament patriarch. And his words are a kind of prophecy” (Yanofsky 14). A self-appointed redeemer of whites captured by Indians, Nellis seems to be a paradoxical proponent of becoming-Indian. He is a Tory and a loyalist, a captain in the King’s Regiment, yet it would seem he eventually comes to feel no real sense of allegiance to either side in the American Revolution. For Nellis, war is a “species of conversation” more than a political conflict (17). “The main effort for any man on the frontier” he suggests, “is the effort to understand the messages” (17). Nellis interprets the messages as questions: “Why am I here? Who is the other? What is he saying?” (17).

According to Nellis, the American Revolution turns the world and people upside down: “I do not know if we are sane or insane, the world is so topsy-turvy. The war is like a whirlwind, and the structures of our lives (army, Indian, colonist) have been upended” (79).[8] Like Mary, Nellis suffers from headaches that cause him to feel “split in two,” and his physical symptoms are similar to the effect of the Whirlwind mask (81). “The right side is on fire,” he explains, “and the left is in shadow” (81). Like his face, Nellis’s subjectivity is split: “What I believe is that I am split (we are all split) between what we dream (Indian) and what we fear is true (white)” (106). In his “Address to Pilgrims,” Nellis preaches a doctrine that is founded on loving difference, and in which becoming-Indian is, like the Deleuzo-Guattarian notion of becoming, about entering into a relationship of proximity to the other:

Once I said that becoming an Indian was like unto entering a swarming madness, but it might redeem you. I mean going out of yourself, abandoning the structure of mind which is peculiarly white, entering that area where, because it is neither one nor the other, you are nothing. (173)

For Nellis, becoming-Indian is about relinquishing one’s identity with the majority and its domination over other minoritarian identities. This is also important for Deleuze and Guattari: “Woman: we all have to become that, whether we are male or female. Non-white: we all have to become that, whether we are white, yellow, or black” (470). Moreover, it is not a question of identifying as either white or Indian, but of being comfortable with being somewhere in-between. Nellis describes the process of becoming-other as one that ends with becoming-nothing. His own madness and his belief that his brain enters a “process of disintegration” influence this idea when he settles in Canada (173).[9] He is not fearful of this process; as he says, “I am against the future. But I firmly believe that out of the collapse of everything something new arises” (182).

Similarly, for Deleuze and Guattari, the goal of all becomings is becoming-imperceptible. “The imperceptible is the immanent end of becoming, its cosmic formula” (279). Becomings move in “molecular segment[s]” that begin with becoming-woman and that are all “rushing toward” becoming-imperceptible (279).[10] What becoming-imperceptible means is “to be like everybody else” (279), just as for Nellis it means, “entering that area where, because it is neither one nor the other, you are nothing” (173). As Deleuze and Guattari explain:

Such is the link between imperceptibility, indiscernibility and impersonality—the three virtues. To reduce oneself to an abstract line, a trait, in order to find one’s zone of indiscernibility with other traits, and in this way enter the haecceity and impersonality of the creator. One is then like grass: one has made the world, everybody/everything, into a becoming, because one has made a necessarily communicating world, because one has suppressed in oneself everything that prevents us from slipping between things and growing in the midst of things. (280)

There is, then, a redemptive quality in becoming-indiscernible. While it does not necessarily erase difference, it does enable “a communicating world” open to slippages between different things, where, as Nellis suggests, we can attempt to understand the messages of the other. As Oskar explains, Nellis regards becoming-Indian as redemption, as a process that opens one up to greater potentials for life and love of difference. Nellis teaches his son that “for a White Man to become an Indian is like entering a swarming Madness. Becoming an Indian is difficult as knowing the Truth or becoming a Child agin [sic]. But it might redeem you” (100). Lunacy, Oskar explains, effects “a breach in . . . understanding which allows a new perspective” (180). Neither this nor that, but in-between.

For Deleuze and Guattari, becomings are also redemptive, because they “rend” us from a “major identity” (291). This is why the subject must always pass through becoming-woman first:

In this sense women, children, but also animals, plants, and molecules, are minoritarian. It is perhaps the special situation of women in relation to the man-standard that accounts for the fact that becomings, being minoritarian, always pass through a becoming-woman. . . . In a way, the subject in a becoming is always “man,” but only when he enters a becoming-minoritarian that rends him from his major identity. (291)

For Nellis’s son Oskar, the Iroquois are the other, the molecular minoritarian segment he must pass through in order to “rend” himself from “his major identity.” In words that sound uncannily like Deleuze and Guattari’s, Oskar explains his relationship to the Iroquois:

Difference is their primary characteristic. It envelops them in a luminous sheath. They seem marvelous, more real than real. They become everything that is not familiar, expected, and routine. They become the mystic other, the female, the child, and the self, which I glimpse only fleetingly. (66)

Yet Oskar’s attempts at becoming-Indian are often suspect. When he shaves his head and wears a scalp lock or “practices walking like an Indian,” Oskar claims that “the world looks different” (101). However, Nellis regards his son’s becoming-Indian as an imitation grounded on “naïveté and false bravado” (119). Oskar seems incapable of distinguishing between becoming-Indian and “going-Indian” (a difference that is grounded in sincerity). This may have something to do with Oskar’s attitude towards the Indian and the fact that he has not yet learned to embrace difference, to follow his father’s “11th Commandment,” which is “Love difference” (173).[11] As he writes in one of his letters to General Washington: “This War has turned my Brain upside down. That wch I loved I hate & that wch I oncet hated I love. Such Inconstancy is a Sin” (137). Mary, however, believes that

Under his clothes, Oskar was half-Indian. Except when he was writing things down (he collected facts like butterflies, pinning them to the pages, dead) . . . He had an affinity for the edges of civilization—people at the edge are always closer to the other, more tolerant of difference; this tolerance brands them as sinful; it is a brand and a badge. (165-6)

Strangely, it is only after he has entered into the process of writing the book about Indians (and failed) that Oskar is able to relinquish the desire to master his subjects and truly come to “love difference.” This is when he learns that becoming-other is not, as Deleuze and Guattari warn, about imitation and identification. As Mary points out, he must recognize that he is “half-Indian” underneath his clothes, in his heart rather than by imitation. He must not “go-Indian” but become-Indian, with sincerity and a desire to create a communicating world. One must be aware, as Oskar says, “In Life, we should not pretend lest We lose ourselves & become that wch we pretend to be. When you wear a Mask, you become the Mask” (185). This does not mean one should not do it, however. Oskar follows his warning with the admission that he is “haunted” by his father’s words: “But it might redeem you” (185).

“No longer white or Indian, what might we become?” (Glover 180). “Nomads” is one possibility that Glover, Deleuze and Guattari might all agree on because, as Deleuze and Guattari suggest, “The life of the nomad is the intermezzo” (380). For Glover, being “a nomad, an expatriate, and a wandering Canadian” is part of his process of becoming-writer (Yanofsky 15). Nomads are always becoming. .

.

The Book. The Book About Indians..

[C]ontrary to a deeply rooted belief, the book is not an image of the world. It forms a rhizome with the world, there is an aparallel evolution of the book and the world; the book assures the deterritorialization of the world, but the world effects a reterritorialization of the book, which in turn deterritorializes itself in the world (if it is capable, if it can). Deleuze and Guattari 11

. By recording facts, the book separates the world of facts from the flow of memory, from individual consciousness, from poetry.

This is Oskar’s dilemma throughout the novel. He writes to knit up the tear in his life, but the thing keeps unravelling again behind him. At the moment of writing, though, he feels better. So the book remains a mystery, even to us. It is an impossible object. It both condemns and redeems us. Glover, Interview with Yanofsky 14

.

For Deleuze and Guattari, books are not reflections or representations that simply mirror life or the world. By suggesting that the book “forms a rhizome with the world,” Deleuze and Guattari rescue it from arborescent structures that limit how we understand the relationship between the two. The book engages with the world and the world engages with the book; this engagement has the potential to “deterritorialize” but also to “reterritorialize” each, meaning they can have a liberatory, but also a mutually confining, relationship.

Glover understands the book in a similar way. For him, the book has a relationship to the world, the “world of facts,” that is similar to the Deleuzo-Guattarian idea of the book. He explains the dilemma of Oskar, whose Book about Indians often frames or directs the other narratives of The Life and Times of Captain N., as one that is involved in negotiating this relationship between the world and the book. Oskar’s writing is an attempt to “knit up the tear” between the two—to “deterritorialize” them—but his attempts are often thwarted by the tendency to “reterritorialize.” As Glover puts it, “the thing keeps unravelling again behind him.” Oskar’s desire to connect the world and the book may be impossible, but as Glover suggests, the attempt makes him “feel better.” When he suggests that the book “both condemns and redeems us,” Glover seems to be embracing the ambivalence of its potential to deterritorialize and reterritorialize ad infinitum.

Oskar’s compulsion to write is often a response to the “call to battle” of his teacher, the humpbacked dwarf, Witcacy (31). “Are you ready? he shouts. Are you ready to write? Are you ready to tell the truth?” (32). But as much as Oskar may seek to tell the truth, his Book about Indians is constantly unravelling and undoing itself. As he later confesses, “the book about Indians is not (a) a book or (b) about Indians. It is about Indians tangentially. And it is incomplete and unorganized, sheaves of notes sewn with a thread, scattered about” (65). As Oskar comes to recognize, the reason his book about Indians is not a book about Indians has to do with his understanding of history, which changes when he compares the history of literate cultures to the dreams, myths and legends of native oral cultures. “Scholars of savage lore err in concluding that the native myths and legends are a primitive form of history” he observes. “They are nothing like history, which is an hypothesis about past events, cast in terms of cause and effect, based on evidence and stretching further and further back in time” (82-3). It is the very act of writing a book about Indians that destroys them because writing is antithetical to the oral nature of their culture. As Oskar observes, “the savages are fading now because they are being written—by writing this book, I erase any number of those creatures which I hold most dear, my subjects. The real challenge, the hardest thing of all, is to write a book about Indians” (83).

The difference, as Oskar comes to realize, has to do with the relationship the two cultures have to the present. “Savages dream in order to remember; we write in order to forget” (83). While the Western notion of history follows what Deleuze and Guattari would call a linear or “punctual system,” the function of dreams in an oral culture is closer to the Deleuzo-Guattarian notion of “becoming” in relation to time and the past. Deleuze and Guattari state that “Creations are like mutant abstract lines that have detached themselves from the task of representing a world, precisely because they assemble a new type of reality that history can only recontain or relocate in punctual systems” (296). As Oskar discovers, “By writing history down, we try to extend the explanation of the present deep into the past. But the savage, in his dreams, seeks to extend the present laterally, as it were, across the axis of time” (Glover 83). The dream has a more creative relationship to time; by “detaching itself from the task of representing a world,” the dream (and the Indian) can assemble “a new type of reality” in a manner history cannot.

As Oskar comes to have greater respect for the native oral culture, his book becomes “an antibook”:

The book about Indians can’t be a book at all. (As a book, I agree, it’s a mess, no substitute for all the histories, geographies, anthropologies, and novels that will one day illuminate the subject of Indians.) It is a song, a hymn, a keen, a cry of mourning and condolence. It is a recitation of names, a string of masks, a prayer. It is a break, a rupture in the whole cloth of normal discourse. It is an antibook meant to destroy all books. It is pure ritual, mumbo jumbo, words of power, a spell—not to be read as a book at all, but to be incanted over and over until it infects the soul, until the words pierce the skull and suck out the brain, until the brain is turned upside down. (121)

Oskar’s book becomes an antibook once he ceases to understand history in the traditional sense of literate culture and embraces the native way of being in the present.[12] “Part of the difficulty of writing a book (first impossible project) about Indians (second impossible project) is that the Indians themselves do not recognize our distinction between knowing and being. What they know or say or remember about themselves they are” (109). As Oskar says, “The book about Indians is against the being of Indians” because “the Indians believe that by telling the stories they are. They exist in the telling of stories, the singing of songs, the dancing of dances” (109).

Oskar’s book about Indians becomes an anti-book at the moment when he too ceases to distinguish between being and knowing, which becomes possible only when “the brain is turned upside down,” allowing for the potentialities of a new perspective. His book becomes an act—“a song, a hymn, a keen, a cry of mourning and condolence”—when Oskar relinquishes his need to write a history and to control the subjects of that history. Most importantly, as it becomes an anti-book, it becomes, like A Thousand Plateaus, a book that enacts a becoming. “If you read the book the correct way,” Oskar advises, “you will become an Indian (that is what I intend; that is the purpose of all books that are not books)” (121). As Deleuze and Guattari explain, creative pursuits such as “Singing or composing, painting, writing have no other aim: [but] to unleash these becomings” (272). .

.

Some Conclusions: History and Nomadology. War and Love..

What counts is that love itself is a war machine endowed with strange and somewhat terrifying powers. Deleuze and Guattari 278.

The War has taught me a Grammar of Love. We—Rebels & Tories & Whites & Indians—are having a violent Debate whose Subject is the Human Heart, its constituent Elements & Humors, its hidden Paths. This is a Mystery. The Effect of the Argument, the Structure of its Thought, is a curious Splitting or Splintering. Glover 162

.

History and Nomadology, War and Love: such binaries seem out of place in an essay that wants to be undoing dualism machines. However, as Deleuze and Guattari tell us, “We invoke one dualism only in order to challenge another. We employ a dualism of models only in order to arrive at a process that challenges all models” (20). It is when these dualisms collide that the whirlwind is created; the brain is turned upside down.

[O]nly nomads have absolute movement, in other words, speed; vortical or swirling movement is an essential feature of their war machine (Deleuze and Guattari 381).

Deleuze and Guattari themselves are guilty of opposing History to Nomadology when they write, “History is always written from the sedentary point of view and in the name of a unitary State apparatus, at least a possible one, even when the topic is nomads. What is lacking is a Nomadology, the opposite of a history” (23).

I think what Glover attempts to do in The Life and Times of Captain N. is to write a novel that is between History and Nomadology, one for which he, as a half-Canadian, half-American “nomad” is particularly well-suited to write. As he explains,

I’m a nomad, an expatriate, a wandering Canadian (which is worse than just being a Canadian, I am doubly displaced, a Canadian squared), and I can no longer tell whether that’s because I am a writer or why I am a writer. Some mornings I wake up and it’s a problem. Some mornings I wake up and it’s a dance. (Yanofsky 15)

Glover’s novel is in-between history and fiction;[13] he creates a space in which dualisms collide, creates a whirlwind, a rhizome that turns North America upside down.

Of course it [America] is not immune from domination by trees or the search for roots. This is evident even in the literature, in the quest for a national identity and even for a European ancestry or genealogy (Deleuze and Guattari 19).

Glover thwarts this “domination by trees” by subverting the “quest for a national identity.” Neither Rebel nor Tory, White nor Indian, American nor British, what might we become? Canadian nomads? I am aware that the idea of a “Canadian nomad” seems to contradict my argument about the subversion of national identities. However, Glover suggests that Canada is a place that embodies in-betweenness very well. “Canada is a cracked mirror, a splintered psyche,” he explains, “the idea of being against the future and, consequently, somehow outside history is a powerful theme in the discourse of Canadianism” (Yanofsky 15).

I chose the two quotes on love and war for my epigraphs to this section, in which I am attempting to draw some conclusions, because they each connect a “grammar of love” to the terrifying possibilities of a war machine. “All’s fair in love and war?” Not quite. But the “terrifying powers” of war to effect a splitting, a splintering of identity seems to be a creed common to both The Life and Times of Captain N. and A Thousand Plateaus. And somehow, this “violent debate” that is war becomes, in the whirlwind, in the becoming, a “Grammar of Love.” Dualisms become each other. Love itself is a war machine. Perhaps this is because, as Hendrick tells Mary, “violence has its own strange and perverse beauty—at least it makes you pay attention. You get to know a man when you’re a-killing him, or he’s a-killing you” (168).

Returning to one of Massumi’s earlier questions—“Does it work?”—I feel some of the anxiety Oskar expressed when he acknowledged the messy state of his book. My attempt to write rhizomatically has not been entirely successful—this paper is somewhere between a rhizome and a tree. But perhaps this is the best strategy—a happy accident—for a paper that seeks an in-between space connecting two texts, a paper that is not, in fact, about Indians or History, but about becomings, nomads, wandering expatriates, whirlwind masks, chaos and books that are not books at all.

—Cheryl Cowdy

Notes

1 Douglas Glover, The Life and Times of Captain N., Epigraph ([ix]). [[2]] Deleuze and Guattari oppose rhizomatic to arborescent systems. While the tree is a linear model that is suggestive of genealogies and origins, rhizomes (such as bulbs and tubers) are founded on principles of multiplicity and alliance. See the chapter “Introduction: Rhizome,” 3-25.[[2]]

Works Cited

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translation and Foreword by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1987. Fenton, W. N. Masked Medicine Societies of the Iroquois. Ohsweken, Ontario: Iroqfrafts Reprints, 1984. Glover, Douglas. The Life and Times of Captain N. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1993. Grosz, Elizabeth. Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 1994. Yanofsky, Joel. “A Feeling for History.” Interview with Douglas Glover. Books In Canada 23:1 (February 1994): 13-15.

.

.