Sydney Lea here attacks head on the dread subject of sex but manages somewhat quixotically to ride away (on a Shetland pony named Warrior Maiden) into utterly charming reminiscences about his youthful passion for Angie Morton (his version of Dulcinea del Toboso) and a shantytown and “Colored Graveyard” he would pass traveling to and from her house. This is an instance where an author makes a virtue out of necessity, doing a masterful job of being entertaining while not writing about what he doesn’t want to write about. As Syd writes, “Before I was able to publish the one and only novel I ever composed, for example, my agent had practically to horsewhip me into juicing up my characters’ erotic encounters.” Here are beautiful, lapidary lines: “Unrequitedness thus became, as I say, an expectation.” And a sweet reflection on the complexity of life which, yes, casts up metaphors that we spend the rest of our days decoding.

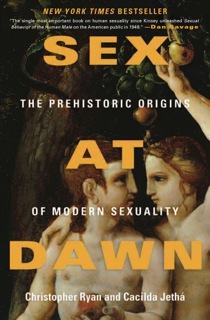

This essay, along with two others, “Unskunked” and “Becoming a Poet: A Way to Know,” published earlier on Numéro Cinq, are among Sydney Lea’s contributions to a book he has co-written with fellow poet laureate Fleda Brown. The book is called Growing Old in Poetry: Two Poets, Two Lives and is forthcoming as an e-book in April from Autumn House Books. The pattern of the book is a call-and-response. As Sydney writes, “My friend Fleda Brown, lately poet laureate of Delaware but now escaped to northern Michigan, and I are writing a book together. She writes an essay on a topic (food, sex, clothes, houses, illness, and wild animals); then I write one on the same topic. Then I write one and she follows suit. Etc. It’s fun, though I don’t know who in Hell will publish it.” We have also published here one of Fleda Brown’s essays from the book, her wonderful meditation on books and reading, “Books Made of Paper.” And in our March issue, we’ll have another. I will be sorry to see this series end for us. (But buy the book.)

dg

A tricky one for me, this subject. Its once-upon-a-time factor must start at ten years old or so, before I understood sexuality except by some vague surmise, In those days, I habitually rode Warrior Maiden, my fat little Shetland pony, past Angie Morton’s house. Angie was sixteen, I think, and movie star beautiful, at least in my eyes. She was scarcely taller than I, and would never grow taller, but her figure was simply statuesque. She had raven hair, almost chalk-white skin, and the most penetrating eyes, ice-blue, almost white themselves, I had ever seen or would ever see after.

My hope, often enough repaid, was to catch her in her yard or, far more exciting, for reasons I must also have dimly surmised, through her bedroom window. No, that’s not accurate: the compensation for my hope was never adequate. True, I couldn’t conceive what satisfaction might entail, but I knew Angie’s languid wave or, on happier occasions, her desultory word or two of chitchat was not it.

So desperate was my need for this young woman, whatever that need comprised, that I frequently extended my rides just so I could pass her house more than a single time on a single ride. I remember tethering Warrior Maiden to an apple tree and simply sitting under it for as long as I could bear, gorging on the wormy windfalls till I made myself queasy. At least I thought the fruit was to blame for how I felt.

These delaying maneuvers resulted once in a frightening but thrilling trip home after dark. In our corner of Montgomery County lay a small settlement of southern-born blacks, who had made the hard trek north in search of better fortunes. Most of them went to work in an asbestos mill in Ambler, though a fair share took jobs on local farms, or, if they were women, they labored as domestics in the more prosperous households. I found their little dwellings fascinating and somehow foreboding: in the warmer months, the front doors seemed always open, but the interiors were kept so dark that I could never quite make out the figures inside. In one tiny house, a harmonica seemed always to be playing, though I couldn’t find the musician. Each shack seemed multi-generational: I could tell that much by the wide variety of human heights among the shadowy occupants.

The shantytown had an aroma of cuisine, exotic, at least to me, pungent, and attractive; but the truly unusual feature of the community was its cemetery, with those knife-thin, tilting headstones, each adorned and surrounded by shards of broken glass, and the bordering trees full of suspended bottles. To ride by that half-acre graveyard plot after sunset, and after having laid my adoring eyes on Angie; to hear indistinct rustlings of nocturnal animals in the brush; to be forced to rely solely on the pony’s sense of where home lay: this mixture of adventure, reverence, mystery, fear and trespass would come to serve as a kind of under-aura to such sexual experiences as I would have in my adolescent years– and later ones too.

However strangely it strikes me today, I seem somehow to have believed that my life would never amount to anything, that I would never know that obscure condition people called happiness, if I couldn’t be with Angie, even if, as I’ve conceded, I didn’t understand what that sort of “being with” entailed.

The notion was absurd, of course, and yet it didn’t end as I came to maturity, at least of the physical kind. For too many years, I would spot a woman in some public place– museum, train, airport, restaurant, campus– and would be convinced that if I could not know her in the Biblical sense my entire life would be no better than despair. The inane measures I took to guarantee myself, if not a conversation with her, at least a glimpse of my exalted Angie were paltry compared to the extraordinary lengths I went to in order to put my person in the way of these coveted women. I can’t even describe the sanest of those tactics, so embarrassed do I remain by reflection on them.

The tactics, of course, were almost always met with rebuff, or simple non-recognition. Indeed, such a response was no more than I expected, the expectation itself a carry-over from my horseback days. Not that Angie ever cruelly rejected me. I suspect she knew full well the profundity of my crush on her, but she spared me all mockery, let alone recourse to nasty words. She appeared always to have enough time for a brief exchange of remarks, which I both craved and resented.

None of her acknowledgments was enough. However banal my part in the conversation, I always hoped she could read it allegorically somehow, could know that my commentary on the weather, for example, was freighted with double-entendre. Alas, she never appeared to decode the allegory, and despite my knowing, even at ten, that her failure to do so owed itself to my own clumsiness and to no defect in her, I was free to regard the failure as a kind of dismissal. Unrequitedness thus became, as I say, an expectation, though being the oldest son of a mother whom I seemed always to disappoint must have factored into all this too. That, however, is another story. Or at least I choose to think so.

I will be forgiven for lacking the temerity as a child to declare my devotion to the paragon Angie. But that I should remain oblique, even prudish to this day when it comes to talking about sex seems an odd thing, so elaborate and ardent were my efforts as a young man to get as much of sex as permitted by such charm as I owned and by 1950s mores, which I felt both thrill and shame to violate when I could. Before I was able to publish the one and only novel I ever composed, for example, my agent had practically to horsewhip me into juicing up my characters’ erotic encounters. Though the first draft referred to those encounters, it stopped leagues short of depicting them. In forty years of teaching, for further instance, I never felt other than acutely uncomfortable when discussing student work that showed significant carnal content.

One problem that has always concerned me, at least in my avatar as prose essayist, is what I call the temptation to closure. That is, I may lay out a series of memories, emotions, and events, and then discover myself hunting for a way to herd them into a narrative corral. I don’t know if that’s what I am doing here. I honestly do not. In any case, I wonder if my unease in talking about sex out loud or on the page may go back to a certain horseback ride after dark, when – full of vague lust, longing, and melancholy– I passed what was then referred to as the Colored Graveyard. The sense, as I lingered under Angie Morton’s window, that I was on the brink of an exciting but forbidden trespass may have been further impressed on body and soul by my traveling on horseback by those darkened cabins, each so full of mystery, then under those suspended bottles, which seemed to betoken a universe I had no right to visit. That, after all, was what made it so scintillating to imagine.

—Sydney Lea

——————————–

SYDNEY LEA is Poet Laureate of Vermont. His selection of literary essays, A Hundred Himalayas, was published by the University of Michigan Press in September, 2012. Skyhorse Publications just brought out A North Country Life: Tales of Woodsmen, Waters and Wildlife, and in April, his eleventh poetry collection, I Was Thinking of Beauty, is due from Four Way Books. His most recent collection of poems is Six Sundays Toward a Seventh: Selected Spiritual Poems, from publishers Wipf and Stock. His 2011 collection is Young of the Year (Four Way Books).

He founded New England Review in 1977 and edited it till 1989. Of his nine previous poetry collections, Pursuit of a Wound (University of Illinois Press, 2000) was one of three finalists for the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. The preceding volume, To the Bone: New and Selected Poems, was co-winner of the 1998 Poets’ Prize. In 1989, Lea also published the novel A Place in Mind with Scribner, and the book is still available in paper from Story Line Press. His 1994 collection of naturalist essays, Hunting the Whole Way Home, was re-issued in paper by the Lyons Press in 2003. Lea has received fellowships from the Rockefeller, Fulbright and Guggenheim Foundations, and has taught at Dartmouth, Yale, Wesleyan, Vermont and Middlebury Colleges, as well as at Franklin College in Switzerland and the National Hungarian University in Budapest. His stories, poems, essays and criticism have appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New Republic, The New York Times, Sports Illustrated and many other periodicals, as well as in more than forty anthologies. He lives in Newbury, Vermont, where he is active in statewide literacy and conservation efforts.