My Back Pages is the closest Moore will ever come to completing his massive study of the emergence and development of the novel —Jeff Bursey

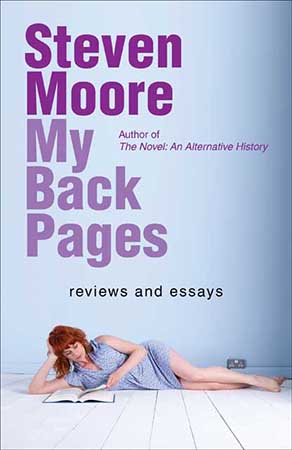

My Back Pages: Reviews and Essays

Steven Moore

Zerogram Press, 2017

$30.00, 767 pages

.

Introduction

In the mid-1980s, while doing research for my thesis on Henry Miller—a person and subject not popular within Memorial University of Newfoundland’s English department, the choice solidifying my dubious reputation among conservative professors from England and Newfoundland—I read Frederick R. Karl’s critical survey, American Fictions: 1940-1980 (1983). Apart from a few generally dismissive remarks on Miller, indicating a lapse of judgment, this work introduced me, in one giant, dual-columned flow of crackling prose and sharp observations, to authors that I never heard about in university classes. One of them was William Gaddis, whose two published novels (at that time) were discussed at great length. What I read intrigued me, but thesis writing and an imminent marriage, as well as a subsequent move, occupied my mind. In 1986, shortly before leaving Canada, I ordered Gaddis’ three works (a new one had come out the year before) and they accompanied me to London, England, where my then-wife’s studies took us. I resisted reading them as the final draft of the thesis required attention. At some point I needed a break, and soon found myself 600 pages into The Recognitions (1955) with 300+ to go, my spirits uplifted by Gaddis’ monumental first book, a reminder of how genius trumps talent, a salutary blast of corrosive satire and humour in a bleak time (little money, grey weather, England under Thatcher), a rebuke to the palsied minimalism of the 1980s that infested magazines and publishing lists—and suddenly Karl’s term for Gaddis, “tribune,” made sense. With the thesis finally sent to MUN, I turned to the remaining pages of The Recognitions, then to J R (1975), whose technical brilliance and humour helped preserve my sanity while I worked in a warehouse, and then the less impressive Carpenter’s Gothic (1985).

Back in St. John’s in September 1989 I came across a segment from another Gaddis novel in a 1987 New Yorker—what would be published in 1994 as A Frolic of His Own—and also, for the first time, read critical books devoted to his work. There weren’t many. At a guess, 1990 marked the year I first encountered Steven Moore (b. 1951) through his invaluable guide to The Recognitions. For 27 years, in one form or another, my Gaddis reading has been deepened and expanded by Moore. A recent example of the continued efforts at explicating Gaddis, who Moore considers “the greatest American novelist of the 20th century,” and how that can lead to a profounder understanding of his literary worth—and the worth of literature itself—can be found here in a joint review of books by Moore, and Joseph Tabbi, another Gaddis scholar who completes, for me, the triumvirate of Gaddis’ best critics.

In the early 1990s, Steven Moore worked for Dalkey Archive Press, home of The Review of Contemporary Fiction (RCF) and one of the most eclectic publishers around. From 1988-1996 he reviewed for RCF and eventually, as an editor, helped bring into print, among others works, David Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress and Reader’s Block and several Rikki Ducornet novels. Behind the scenes, and in front of my eyes, Moore shaped some of my reading (and I daresay that of others). There aren’t many critics so tireless in fighting critical indifference, small sales, and much more for high-risk writing.

There are reasons for this autobiographical introduction. While My Back Pages contains much about Gaddis that, as a fan, I appreciate seeing either for the first time or between covers at last, in this immensely readable, encyclopedic, and essential work there are almost 400 pages of concise reviews, published between roughly 1975 and 2016, of short-story collections, novels, and nonfiction, followed by almost 350 pages filled with meditations on key figures in Moore’s life, including his friend David Foster Wallace, Alexander Theroux, and W.M. Spackman. In these pages—revealed incidentally when its contents were first printed and forming a more than rough sketch when collected—is a partial intellectual autobiography that reveals, now and then, and almost always unexpectedly, his beliefs, his likes and dislikes, his confrontations with ideas and people, and reversals, criticisms, and disappointments in his career and personal life.

Certain figures recur: apart from Gaddis, Markson, Ducornet, and Theroux, there is much on Ronald Firbank, the Beats, Malcolm Lowry, Gilbert Sorrentino, and James Joyce. Certain predilections are as numerous: metafictional and/or experimental works, with occasional excursions into other forms. “It’s the books I write about, many of them forgotten by now, more than the pieces themselves, that deserve to be remembered,” he states outright, though that note of humility goes against the many years in service to literature exemplified by the length and depth of this book (indeed, the length and depth of each Moore book). In individual pieces he is not as shy in taking credit where it’s due.

One of Moore’s best qualities as an explicator is in communicating complex or complicated material in the clearest possible terms, and with humour when possible. Not all is sunshine, though, since every book is written, implicitly and explicitly, against something. There is even the presence of a dark figure that, while not a villain, is an adversary. And there’s sex. How-to guides to crafting correct fiction by James Wood or dreary musings on the uselessness of writing by Tim Parks aren’t going to offer this combination of features.

.

I.

My Back Pages is the closest Moore will ever come to completing his massive study of the emergence and development of the novel: The Novel, An Alternative History: Beginnings to 1600 (2010), and The Novel, An Alternative History: 1600–1800 (2013). (In 2014, the second title won the Christian Gauss Award for literary criticism.) “Rethinking the History of the Novel,” an essay placed near the end of the new book, supplies several reasons why he didn’t proceed with a third volume. Partway through the second volume his self-appointed task “became more like a chore, which is exactly what I had hoped to avoid when I began… by the time I wrote the last page of the second volume, I had no desire to go on to the third volume that I had been planning on from the very beginning.” Further:

Even though I had planned to narrow my focus at that point and concentrate only on innovative, experimental novels, I realized it would take me another five years at least working full-time and another thousand pages to cover 1800 to the present, and I finally had to admit that I had bitten off more than I could chew. Now I understood why no one had written a comprehensive, universal history of the novel before, and also understood why such things are only attempted in multi-volume university press series overseen by general editors with troops of contributors at their command.

Moore states he had no grand plan in mind when he began his labours, and yet, thanks to perseverance, missionary zeal, and an enthusiasm buoyed, I suspect, by ceaseless reading, this full-time independent scholar completed what only university presses could achieve. Perhaps it’s best that writers unthinkingly create their own follies. He felt provoked by “the conservative Bush [the Younger] administration of evil memory”—how those years must now seem, while in no way golden, less terrible than the present Republican government—that allowed “a corresponding reactionary backlash against the innovative, unconventional novels I love…”

Considering the fatigue factor, then, My Back Pages might be a better work than the never-realized third volume. Its content differs from that of the Novel works, which together are a magisterial, yet colloquially spoken, introduction to hundreds of fictions from ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, on to Ireland and Iceland, then Mesoamerica, Japan, China, Europe, and North America. Moore’s new work comprises spirited defenses, campaigns, and hosannas for the lineage of “unconventional” writers he has long admired. The tempo is that found in breaking news, in Ezra Pound’s sense, excited but not sensationalized. (I’m reminded of what Sven Birkerts says in Changing the Subject [2015]: “I recognized at that moment that if art really is an act of concentrated attention, then it is also at the same time a power, not only carrying its messages, the content that is its pretext, but also storing—and making available—an enormous compacted energy. I’m talking about the energy that made the vision and expression possible in the first place.” Substitute criticism for “art” and that suits Moore’s energetic prose.) Instead of plot summaries devoted to the literary output of one country, we are provided with brief summaries of works and essays focused on single topics. After the Introduction and Acknowledgements, the sections are: Reviews; Miscellaneous Nonfiction; and, in three parts, Essays (“William Gaddis and Friends”; “Significant Others”; “Personal Matters”).

Set out alphabetically, the reviews (sometimes single entries, at other times sequences devoted to the same author), to provide a brief list, are of works by Djuna Barnes, Robert Coover, Stanley Elkin, Mo Yan, Severo Sarduy, Arno Schmidt, and Marguerite Young. In addition to what Moore has written for Rain Taxi and the Washington Post, among other places, most of the reviews appeared in RCF. He is most often a polite and eager reader, inclined to treat with the greatest respect metafictional works and meganovels that display erudition and contain recondite language used in a playful way, works that emphasize style over plot (or character) and that break the constraints of the novel. The “anemic stories” of minimalists rarely capture his attention, but in considering Stephen Dixon’s Frog (1991) he does concede that this book “represents an interesting new hybrid: a long novel made up of short episodes, a maximalist meganovel written in a minimalist style.” So he can be won over if the writer has done something original. A writer can also be a “vixen,” but only if they write well, like Mary Butts or Karen Elizabeth Gordon. (He doesn’t offer an equivalent term for males.)

Moore’s enthusiasm is contagious, as it’s often combined with casual displays of his wide and deep reading. Plucked almost at random are three samples of his writing style. The first is the opening to a review of Nicola Barker’s Darkmans (2007):

’Tis the season of huge literary novels. Those of us for whom size matters welcome with holiday cheer Denis Johnson’s Tree of Smoke, James McCourt’s Now Voyagers, two new translations of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Paul Verhaeghen’s Omega Minor, Alexander Theroux’s Laura Warholic, and the 900-page Adventures of Amir Hamza, an old Urdu novel (by way of Arabia and Persia) newly translated for the Modern Library. Crashing this boys’ club from England comes Nicola Barker’s 838-page Darkmans, her seventh and longest novel, and a finalist for this year’s prestigious Man Booker Prize (which went to a much much shorter novel).

After reading a 3,300-page work by William T. Vollmann, Moore concludes:

Rising Up and Rising Down is a monumental achievement on several levels: as a hair-rising survey of mankind’s propensity for violence, as a one-man attempt to construct a system of ethics, as a successful exercise in objective analysis (almost nonexistent in today’s partisan, ideological, politicized, spin-doctored, theory-muddled public discourse), and a demonstration of the importance of empathy, whether in writing a book like this or simply dealing with fellow human beings. It can be an exhausting, depressing read, but with the ever-growing role of violence in our lives, it is an essential read. And the amazing fact that during the 20 years he spent writing Rising Up and Rising Down Vollmann also published a dozen extraordinary books of fiction—many in the 700-page range and packed with historical research as deep as that on display here—elevates this achievement beyond the realm of mere mortals.

Though Moore generally prefers those whose language sparkles with new thoughts set out in long sentences, he can appreciate other styles, as shown in this review of the first volume of Zachary Leader’s biography of Saul Bellow:

The amount of detail here is staggering; Leader apparently left no stone unturned, and succinctly summarizes all the cultural upheavals surrounding Bellow in those heady days. (The biography doubles as a primer on the intellectual climate of the times.) But the details never become too dense or overwhelming, thanks largely to Leader’s clear, brisk style.

This compliment applies to Moore. Apart from providing readers with a long list of titles to look for, his reviews are models of how to balance an examination of style, a short summary of salient points, and a decision as to a book’s worth.

The Miscellaneous Nonfiction section contains essays and reviews ranging in subject from critical works on literature and postmodernism to human anatomy and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. While of varying interest and engagement, this section offers further proof of the diversity of Moore’s taste, which is, incidentally, also shown in the music citations that appear now and then.

.

II.

In Essays, Part 1, under the section “William Gaddis and Friends,” Moore brings together previously isolated pieces on Gaddis (and those who knew him), including Pynchon, Markson, and Chandler Brossard. Particularly noteworthy is “Sheri Martinelli: A Modernist Muse.” She was an artist-model in Greenwich Village who Gaddis and Anatole Broyard (author of, among other books, Kafka Was the Rage [1993]) pursued romantically, “a protégé of Anaïs Nin,” friends with H.D., Charles Bukowski, Charlie Parker, and the Beats. She later entered into a hazily defined friendship or relationship with Ezra Pound when he was at St. Elizabeths Federal Hospital. (This is the stuff of a biopic.) The concentration of influences and animosities (Broyard versus Gaddis, Pound versus almost everyone) that congregated in this almost unknown artist is fascinating.

Part 2, “Significant Others,” deals with, among others, Kurt Vonnegut, Edward Dahlberg, Brigid Brophy, Leopoldo Marechal, and Wallace again. Barring Wallace and Vonnegut, Moore is paying close attention to the obscure, the out-of-print, and the forgotten, something that other critics could seek to imitate. Firbank, one of “the more recherché modernists” who is invoked often and gets connected to Francesca Lia Block and Alan Hollinghurst, as well as many others, is looked at for his playwriting. While I can agree with Moore on many things, we part ways on Firbank, who he admits is a writer “so idiosyncratic that one instinctively likes or dislikes [him], and no amount of critical persuasion one way or another is going to change anyone’s mind.” This may be a blind spot of mine, just as Moore’s low regard of a fellow Modernist, Henry Miller, is inexplicable considering his influence on and way with language, on issues concerning freedom of expression, and as a figure who supported Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums and The Subterraneans, about whom Moore has much to say (as he does on other Beat writers like William Burroughs and Alan Ansen).

Theroux is both reviewed and the subject of an in-depth description of his second novel, Darconville’s Cat (1981), “a dazzling 700-page satire… that surely will soon come to be celebrated as the finest example of learned wit ever produced in American literature.” As Moore mentions in the Introduction, he sometimes wrote with an “optimism” that was misplaced. Theroux’s work matches Moore’s taste for length, wit, language, digressions and allusions, and several modes of presenting material (“poems, fables, nightmares, a diary, an abecedarium, a blank-verse playlet…”), and he offers a persuasive set of reasons for the importance of this novel. What also arises is one of those welcome contradictions that spring up in any person’s record of literary commentary if they do it long enough. In expressing fervent enthusiasm for and belief in Darconville’s Cat—“I want to be buried with this novel clasped to my heart”—Moore has to restrain from commenting negatively on Theroux’s Catholicism. Critics of the Novels volumes, such as Steve Donoghue and Roger Boylan, noted the evident anti-religious stance, the latter saying that Moore “seems constitutionally incapable of finding any redeeming value in the 2,000-year history of Christianity that has been so much a part of Western culture.” This sentiment extends back to when Moore reviewed Lawrence Durrell’s Livia: or, Buried Alive in 1979: “Denis de Rougemont, to whom Livia is dedicated, is the author of the classic 1940 literary-theological study Love in the Western World (still in print and still worth reading in spite of its Catholic bias).” If we didn’t muzzle ourselves now and then when faced with a work that leaps over our convictions we’d hardly be human, so I’m not going to fault Moore for his surprising moderation.

The third section of Part 3, “Personal Matters,” contains “Nympholepsy,” “Rethinking the History of the Novel,” and “Publishing Rikki Ducornet.” The second has been referred to already; the third details Ducornet’s history with Dalkey—who published her books The Fountain of Neptune (1992), The Jade Cabinet (1993), The Complete Butcher’s Tales (1994), and, both in 1995, Phosphor in Dreamland and The Stain—and her and Moore’s author-editor relationship, of which he is clearly proud. As to “Nympholepsy,” that will be dealt with below.

.

III.

As already noted, Moore wrote his two Novel books to stand up for the kind of fiction he saw under assault from 2000-2008, and in his introduction to the first volume he addresses, with withering scorn and an abrasive tone, the narrow-minded criticism that Dale Peck, B.F. Myers, and Jonathan Franzen dealt out to writers of so-called difficult fiction. In My Back Pages there are literary theorists to argue with for their instrumental use of texts “as a springboard to explore socioeconomic/political issues, theories of reading… drifting further and further away from the actual words on the author’s page,” and attempts to redress the “little critical attention” and “critical neglect” experienced by authors like Rudolph Wurlitzer and Richard Brautigan. That’s not to say Moore doesn’t admire this or that critic (full- or part-time); he praises Tom LeClair, Marilyn R. Schuster, and Samuel R. Delaney. Yet the chief foes are those who use this or that text for their own ideological thoughts, and the review outlets that are indifferent to writers, in English or in translation, who present new visions.

One individual does stand out. Those familiar with Dalkey know that John O’Brien is its founder and main force. In the Index there are references under his name, but when the pages are consulted he is identified most often as “boss,” “editor,” and “Dalkey’s publisher.” The Introduction provides context for later remarks:

While at the local warehouse buying stock, I noticed a recently published novel with an irresistible title, An Armful of Warm Girl, read it, and became a devoted Spackman fan thereafter. Shortly after he died in 1990, I began planning an omnibus edition of his complete fiction; it was typeset and ready to go by 1995, but was continually postponed by Dalkey’s boss until a year after I left. (During that time, he moved my introduction to the back and called it an afterword because, as Spackman’s daughter told me, “he felt the length of the introduction might discourage less scholarly readers from starting to read the book.”) The Complete Fiction of W. M. Spackman (1997) was very well received, and I was especially flattered that John Updike referred to my piece as “excellent” in his New Yorker review (but disappointed when he dropped that adjective in his More Matter collection a few years later)… At that time I also prepared a collection of Spackman’s essays that I wanted to publish as a companion volume, but my exit from Dalkey (and the boss’s indifference to Spackman) made that impossible.

The grinding of the axe is audible. Pitting Updike against the “boss” provides pleasure and vindication. Another note airs a different grievance:

I wanted to publish this book [Five Doubts] when Mary [Caponegro] submitted it to Dalkey Archive in early 1996, but the boss adamantly rejected it: “I will not publish this book,” he declaimed in a memo. Upon publication two years later [by Marsilio Publishers], it was very favorably reviewed by Robert L. McLaughlin in Dalkey’s journal, the Review of Contemporary Fiction.

Once again, “the boss” is set up against someone whose opinion dovetailed with Moore’s.

Two final peeks into the workplace demonstrate the toll this took: “Working with Karen [Elizabeth Gordon] was one of the few bright spots during my final dark year at Dalkey Archive.” Lastly: “My years at Dalkey Archive were depressing and frustrating, but Rikki and a few other writers kept me sane and entertained.” The theme here is that Moore felt his editorial instincts were often acute, but that he, apparently, had to wage combat within Dalkey every day. At a future time the full story of the Moore-O’Brien relationship will come out; it won’t be a pretty sight. Without adversaries our lives might be easier, but they do provide fuel for the kind of cold fury that allows a snap to enter one’s sentences.

.

IV.

Above I mentioned this book contains sex. While there are reviews that touch on that, to be accurate I should say that frustrated desire is more often present.

In “A New Language for Desire: Carole Maso’s Aureole,” one of the essays in “Significant Others,” Moore appraises the author’s 1996 novel: “rarely in literature has desire been explored with the intensity Maso brings to Aureole: a pyrotechnic display almost reckless in its abandon, daring in its subversion of literary propriety, and voracious in its erotic hunger.” He goes on to say that Maso

exhibits the kind of bravado and self-exposure that I associate more with rock music divas than with her literary sisters. She has something of Courtney Love’s swagger, P J Harvey’s erotomania (both are mentioned on page 81 of her book), Liz Phair’s bluntness, Kate Bush’s bookish romanticism, Siouxsie Sioux’s dramatic flair, Jane Siberry’s wit, Liz Fraser’s mellifluousness, Shirley Manson’s aggressive sexuality, Tori Amos’s introspection, and Lisa Germano’s heartbreaking insecurity.

This eight-page analysis of a Sapphic love story takes us through each chapter of what Moore considers “Maso’s most innovative book to date.” He adds: “Maso goes further than any writer working today to create a style that does justice to the polymorphously perverse energy of eros.” As literary analysis, it is at the usual high standard of Moore’s criticism, showing sensitivity to language use, to how themes reverberate and parallel other content, and exhibiting deftness in locating outside sources (literary, musical) that contribute to an understanding of the text under investigation.

What interests me most is the curious verdict rendered on a psychological condition mentioned in the novel: “Lust here isn’t the devouring hunger of ‘Anju’ or the sexy games of ‘Make Me Dazzle’ but ‘sex addiction’…, that dreary concept from 1980s pop psychology that seems to have some validity here.” Sex addiction is considered a mental condition that, according to some opinions, is a form of compulsive sexual behaviour. It has at times been labelled nymphomania or satyriasis. Moore, who as far as I know is a medical layman, offers begrudging acceptance of the possibility this condition exists. Present as well is an appreciation for the sexual content of Maso’s novel. For me, this 1996 essay ties into the very personal “Nympholepsy” (2001) from “Personal Matters,” which outlines Moore’s self-diagnosis of a condition brought about by his everyday interaction with Morgan, a female fellow employee at a Borders store. Both deal with lust/love, and both reveal an aspect of the critic that heretofore has not been revealed. To say it comes as a surprise is an understatement.

Listing the three “factors… [that] had led to the attack,” Moore gives as the third: “the realization that soon I would turn 50, and that I was still alone—never married, no long-term relationships—and in all likelihood I would die alone without every knowing what it is like to love and to be loved.” He assesses the qualities in Morgan (not her real name) that attract him:

But she was more than just a pretty face (there were other teenage girls working at Borders, as attractive as Morgan): she was quiet, a bit shy, introverted, bookish, artistically inclined—qualities I shared and that led me to regard her as a soul mate, despite our age difference, qualities I had always looked for in a girlfriend but had never found. And of course she possessed numerous lovable qualities I lacked; I could fill the page with them. I had been waiting all my life for someone like this on whom I could lavish all my dammed-up care and affection, and thus Morgan became the unwitting victim of this flood of emotion.

In time he terms his ache nympholepsy, and consults Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita for a definition. (In addition to having himself as a client, he is getting a second opinion from a literary work.) Moore being Moore, he can’t resist a joke: “Taking down my hardcover copy of Alfred Appel’s annotated edition, I fumbled beneath Lolita’s tight white jacket for a few minutes until I found what I was looking for.” The rest of this poignant confession involves consulting dictionaries, poetry, music, several bouts of self-criticism and misery, and much else. In the Introduction he says this about the essay: “It’s my favorite largely because its subject inspired me—which was what nympholepsy originally meant—to open up my style, one that I’ve used ever since whenever possible. (You can see that style develop over the course of the essay, which begins in a flat, documentary voice that turns more lyrical, scholarly, and fanciful as it goes along.)”

We can, indeed, look at this admission primarily as a style issue. Yet this is sensitive ground. The essay is surprising and touching in its discussion of desire and loneliness. Consequently, I’ve decided that even though Moore’s life has been filled with words he’s read and words he’s written, a literary review wouldn’t pay proper respect to this piece, and also that every reader will want to arrive at his or her own interpretation.

.

Conclusion

People wonder why criticism exists and what its function is. When voiced by writers this can be unsubtle code for these thoughts: “What’s the point of it if not to get the good news out about my work?” and “Why do I care what some critic I dunno thought? And what’s exciting about reading a review for a book I haven’t read?” There is also a disdain for those who judge art. Moore doesn’t hesitate to discriminate the good from the bad—he has choice words on Norman Mailer’s The Gospel According to the Son (1997)—based on a simple criterion that he finds also expressed in the works of Spackman: “The content of his novels, and his characterization of women especially, will always create problems for some readers, but not for those who agree that style is what a writer is to be judged by.”[1] For some people, this will come across as elitism that verges on canon making. As well, as Stephen Mitchelmore points out, there is often a “prideful disdain for anyone who attempts to articulate the fascinating void, which actually reinforces respect for this aspect of art it is supposed to be dismissing…” We are fortunate to have a handful of astute critics who bring us reports gathered from the outskirts of the familiar literary world about innovative authors busily deepening our collective literary heritage. Steven Moore has been at the vanguard of criticism and publication of outliers and explorers whose artistic visions reinvigorate the capacious form of the novel and the short story, and we are in his debt.

—Jeff Bursey

Jeff Bursey is a literary critic and author of the picaresque novel Mirrors on which dust has fallen (Verbivoracious Press, 2015) and the political satire Verbatim: A Novel (Enfield & Wizenty, 2010), both of which take place in the same fictional Canadian province. His newest book, Centring the Margins: Essays and Reviews (Zero Books, July 2016), is a collection of literary criticism that appeared in American Book Review, Books in Canada, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, The Quarterly Conversation, and The Winnipeg Review, among other places. He’s a Contributing Editor at The Winnipeg Review, an Associate Editor at Lee Thompson’s Galleon, and a Special Correspondent for Numéro Cinq. He makes his home on Prince Edward Island in Canada’s Far East.

- In Rebecca Swirsky’s review of Danielle McLaughlin’s short-story collection Dinosaurs on Other Planets, titled “Something else entirely,” the first sentence reads: “Good writers rely on style. Even better writers rely on empathy.” If, as a writer, you prioritize empathy, seek a counsellor; if you prefer writing, look for a stylist who has the ability to show empathy if he or she wishes. Times Literary Supplement, May 13, 2016, Issue No. 5902, p. 22.↵

Until Charles Foran’s recent Mordecai: The Life and Times, the various biographies of Mordecai Richler suggest that an interesting subject for biography does not necessarily an interesting biography make. Great lives don’t always inspire great books. In the decade since Richler’s death in 2001, four books entered a biography’s race between early market share, thoroughness and accuracy. Globe and Mail journalist Michael Posner pre-excused the scattershot tone of his 2004

Until Charles Foran’s recent Mordecai: The Life and Times, the various biographies of Mordecai Richler suggest that an interesting subject for biography does not necessarily an interesting biography make. Great lives don’t always inspire great books. In the decade since Richler’s death in 2001, four books entered a biography’s race between early market share, thoroughness and accuracy. Globe and Mail journalist Michael Posner pre-excused the scattershot tone of his 2004