.

1

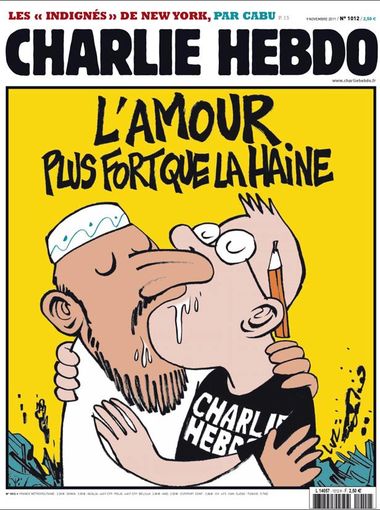

In comments made aboard the papal plane en route to the Philippines in early January, Pope Francis spoke about the Paris terror attacks. According to the AP, he defended “free speech as not only a fundamental human right but a duty to speak one’s mind for the sake of the common good,” and he condemned the murderous attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo. Such horrific violence “in God’s name,” far from being justified, was an “aberration” of religion. In fact, he said, “to kill in the name of God is an absurdity.” Perhaps; but we also know that, absurd or not, killing in the name of God accounts for many of the more irrational streams of blood staining what Hegel famously called the “slaughter-bench” of history.

Francis is aware of the paradox. His very insistence that when it comes to religion “there are limits to free expression,” anticipates his overt conclusion that a “reaction of some sort” to the Muhammad cartoons was “to be expected.” If not inevitable, a response was hardly unlikely. Most Muslims consider any representation of Muhammad, even the most benign, image-worshiping and therefore blasphemous. And radicalized Islamists, a small but virulent minority of Muslims, have demonstrated a willingness to resort to violence when they feel their Prophet has been offended. The pope was not speaking ex cathedra, not pronouncing authoritatively on faith and morals. Still, he was talking about “faith,” insisting that it must never be ridiculed. “You cannot,” he declared, “insult the faith of others. You cannot make fun of the faith of others.” Though these “Shalt Nots” go too far for some, many will be inclined to agree with the pope. In a gentler world I would myself. But this is decidedly not that world.

This seems counter-intuitive. Surely in the post-9/11 world, a world in which the blood-dimmed tide of theological passion has been loosed, it would make all the more sense not to intensify those passions. One strand of the Enlightenment interprets free speech as universal tolerance, including the acceptance of everyone’s right to practice his or her own religion on its own terms, with its own codes and beliefs. But another strand of the Enlightenment—reflecting the same reaction to the preceding century or more of religious conflict, obscurantism, and superstition—is radically secular, and therefore more likely to be dismissive than tolerant of religion in general, especially those creeds whose adherents cling to what seem to secularists atavistic mores—which is to say, counter-Enlightenment values.

That’s our Enlightenment, of course: European and then transatlantic. But, as everybody knows or else should know, Islam had its own sustained enlightenment. During that 500-year period, a unique Islamic culture flourished, while, simultaneously, Muslim scholars became the saviors and conduits of much of Greek philosophy, literature, and science: a rich deposit that eventually resulted in the European Renaissance. The Islamic Golden Age, beginning in the Abbasid caliphate of the great Harun-al-Rashid (789-809) and stretching beyond the 13th century, occurred during a half-millennium when Europe was mired in what, at least in comparison with contemporaneous Muslim culture, actually were the fabled “Dark Ages.” Benjamin Disraeli once squelched in Parliament an Irish MP who had alluded to the Prime Minister’s Jewish heritage by reminding the unfortunate Celt that while “the honorable gentleman’s ancestors were living in caves and painting their bodies blue, mine were high priests in the Temple of Solomon.” Disraeli’s contrast might be applied, mutatis mutandis, to the contrast between European and Muslim civilization between, say, the 8th and the 12th centuries.

But that Golden Age of Islam is long past, replaced by a post-colonial world of vast petro-wealth for the few and abject poverty for the many. The current Muslim Middle East is beset by fundamentalist versions of Islam, protracted violence, widespread illiteracy, lack of opportunity, and the growing sense of parents that neither they, nor their children nor their grandchildren, are likely to develop the skills required to function in a modern global economy. Their region is multiply afflicted by authoritarian despotism in the oil-rich states; sectarian strife between Sunni and Shia; tribal and civil chaos; and the rise of ever-more zealous and brutal jihadists, with ISIS in particular now trying to slaughter and terrorize its way to a grotesquely distorted version of the long-lost Abbasid caliphate.

Western secularists understand, may even admire, Muslim rejection of our often sordid materialistic culture. But from the perspective of enlightened reason, fatwas and jihad are another matter. Bans on images of the Prophet can fall into the same dubious category. Such prohibitions, even if they seem excessive, are understandable to most Western observers. This likely majority would include believers, who, having their own religious faith, have no wish to insult an article of Muslim faith. It would also include secularists committed to the thread of Enlightenment thought that stresses tolerance and a respect for the beliefs of others, even those we may consider idiosyncratic.

There are, however, secular defenders of free speech for whom these prohibitions regarding images of the Prophet become intolerable when reinforced by the threat of violence. That is the camp in which I find myself, awkwardly caught on the horns of a dilemma. How can those of us defending freedom of expression in the name of secular values avoid falling into a binary opposition pitting “us” against “them? Yet what are we to do if our response to Islamist terrorism is to insist, in this matter of banned images, that our secular faith in freedom of thought and expression requires us to insult the religious beliefs not only of Islamist fanatics but of virtually all Muslims? There is no easy answer, and perhaps no middle ground, for those of us who might wish, in the name of amity and mutual respect, to honor such a ban, but resist being bullied into it by the threat of violence and death if we do not.

.

2

Pope Francis, though adamant in condemning violence in the name of religion, advocates tolerance and respect for the “faith of others,” both as an intrinsic value and because he is the world leader of a faith he also wishes to see respected by others. One reason his recent comments received such worldwide attention is that, quite aside from being, for Catholics, the Vicar of Christ, this charismatic pope has quickly become a popular celebrity in the secular world. As such, it might be argued, his observations to intimates on a plane should be taken as just another instance of the unscripted utterances that have charmed those who share this remarkably informal pope’s vision of a less pompous pontificate—though these same spontaneous observations unnerve the Vatican Curia and send church officials scurrying to preempt any potential fallout. Forget it. Given Francis’ immense personal appeal and his spiritual prestige as pope, his comments cannot be reduced, as they were the day after by a Vatican PR spokesman, to merely “casual remarks.” His utterances all carry significant weight.

The troubling aspect of his remarks on the plane—for those who were troubled—had to do not only with those “cannots” regarding religion, but with the immediate political context in which they were pronounced. I applaud his effort to bring together rather than divide. But to condemn, as Francis did on this occasion, “insults” or “fun” directed at “faith” suggests—in the context of the politically and religiously motivated slaughter of cartoonists who did not share that reticence—a partial misreading of events, and of the issues at stake. Some, even admirers of this pope, of whom I am one, have been disturbed by what struck us as a less than full-throated condemnation of religiously-inspired violence, even if the killings in Paris represent, as they do, an “aberration of religion,” in this case, of Islam.

In his remarks on the plane, the pope—reaching out, as always, to what he calls “the peripheries”—was advocating tolerance and mutual respect rather than engaging in a debate about freedom of speech. The complicating factor, as recently noted by Timothy Garton Ash—Isaiah Berlin Fellow at Oxford and leader of the Oxford-based Free Speech Debate project—is that in our contemporary world, a world where writers and cartoonists can be murdered for engaging in religious satire, “the argument for ‘respect’ is so uncomfortably intertwined with fear of the assassin’s veto.” But there may be safety in anonymity. Writing on January 22, Ash proposed, as a way of “Defying the Assassin’s Veto” (New York Review of Books, February 19, 2015), the establishment of a “safe haven”: a website “specifically dedicated to republishing and making accessible to the widest readership offensive images that are of genuine news interest, but which, for a variety of reasons, many journals, online platforms, and broadcasters would hesitate to publish on their own.”

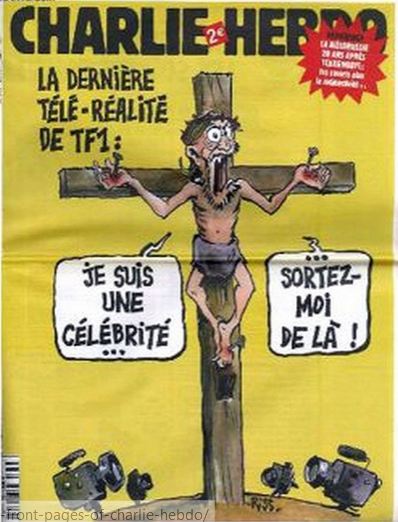

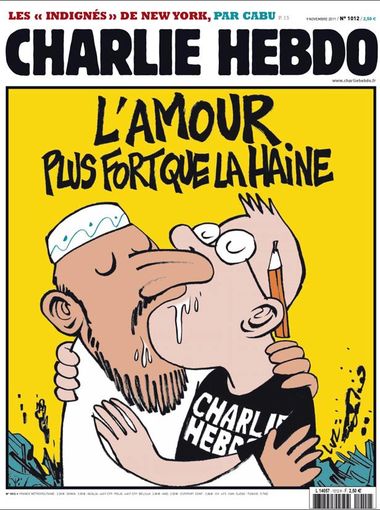

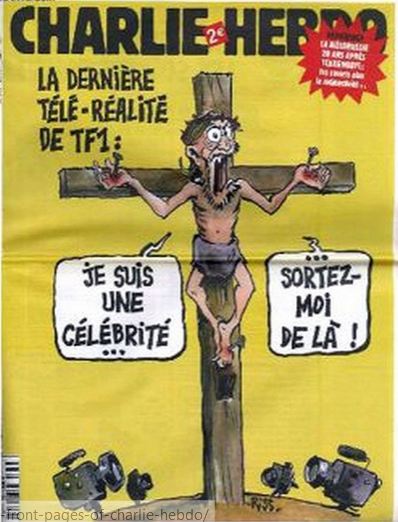

Fully aware of the “no-holds-barred French genre of caricature as practiced by Charlie Hebdo,” Ash does not expect widespread endorsement of the often grossly outrageous satirical attacks the magazine has long launched against a wide spectrum of religious and political figures. Nor does he glibly charge with “cowardice” those editors around the world who, dealing with genuinely difficult choices, elected not to republish the Charlie Muhammad cartoons. But he does applaud Nick Cohen’s refreshingly frank observation, made during a panel discussion at The Guardian (which did not reprint the original cartoons though it did publish, a week later, Charlie Hebdo’s memorial cover, depicting a weeping Muhammad saying “all is forgiven”). Cohen said: “If you are frightened, at least have the guts to say that. The most effective form of censorship is one that nobody admits exists.” As if in response, the Financial Times columnist Robert Shrimsley wrote the following day, “I am not Charlie, I am not brave enough.”

“I am not Charlie” prose quickly became, as Ash remarks, a “subgenre.” In his January 9 NY Times column, “Why I Am Not Charlie Hebdo,” conservative commentator David Brooks made several characteristically sensible points; but not, it seems to me, when it came to what he thought the “motivation” behind the French people’s “lionizing” of Charlie Hebdo. The mass response in Paris and elsewhere had to do, not so much with approval of the offending cartoons; nor even with approval of Charlie Hebdo’s laudable exposure (one of the traditional targets of satire in Rabelais, Molière and Voltaire) of the use and abuse of religion by hypocrites and fanatics. The marchers were “motivated” by a felt need to defend freedom of expression, to champion liberté, rightly seen as under direct assault by the forces of ignorance, religious bigotry, and militant fanaticism.

The perspective of the pope, as of David Brooks, seems to be shared by most media outlets, which had, until recently, refused to reproduce the “inflammatory” cartoons for the general public. True; free speech is not unlimited. There are considerations of sensitivity, respect for the feelings or beliefs of others. And there is the question of public safety: one mustn’t, to cite the usual cliché, shout “fire” in a crowded theater. In addition, especially in the U. S., many—left, right and center—are quite willing to sacrifice freedom of expression when it comes to voices they disagree with, ranging from speech codes on campuses and college committees disinviting controversial speakers, to attempts to ban flag-burning. And, to cite an example mingling outrage, bias, politics, and self-censorship, there is about as much chance of hearing a favorable word about Israeli policy in the UN General Assembly as there is of hearing a disparaging one in the U. S. Congress.

The crucial question posed by the onboard remarks of Pope Francis has to do with his specific defense of religion set in the specific context of a contemporary world threatened, not by Islam, but by radicalized Islamists ardent to participate—as organized terrorists, as affiliates of al Qaeda and its various offshoots, or as lone wolves—in some form of jihad. Religion’s defense of itself against freedom of speech is nothing new, as attested to by the pitiless but pious burning of “heretics” at the stake; the cherum (ritual of expulsion) pronounced against the noble Spinoza, cursed, damned and driven from his synagogue; the imprisonment of writers and thinkers charged with “blasphemy.” The old lethality resurfaced dramatically in 1989. In the year the Soviet Empire collapsed (fittingly, the 200th anniversary of the start of the French Revolution), Ayatollah Khomeini issued his notorious fatwa against Salman Rushdie for the irreverent (but brilliant and very funny) chapter on Muhammad’s wives in his 1988 novel, The Satanic Verses.

Though they joined in deploring the death-sentence against the author, the Vatican of John Paul II, the archbishop of New York (John Cardinal O’Connor), the archbishop of Canterbury, and the principal Sephardic rabbi of Israel also united in taking a stand against “blasphemy.” Pope Francis, not given to dogmatic pronouncements, did not use the word “blasphemy.” But, like Francis now, all these leaders insisted in 1989 that “there is a limit to free expression” when it comes to religion. I may seem to be having it both ways: acknowledging that Francis did not refer to “blasphemy” and at the same time making him guilty by association with those who have employed this term. Not quite.

But the pope does seem to me guilty of mixing messages and muddying the waters by using the occasion of the murderous attacks on Charlie Hebdo to inform us all that we must always be respectful, and “never make fun” of anyone’s “faith,” at the very moment he is also telling us (listen up, ye cartoonists and satirists!) that we and they have to “expect” retaliation of some sort when we violate that taboo. The pope was speaking off-the-cuff and with the best intentions. Nevertheless, this is a taboo he shares, in however benign a form, with most orthodox Muslims and, alas, with Islamist terrorists. In a more formal imprimatur of the “casual” assertion of Francis that “you cannot insult” or “make fun of the faith of others,” there has been a recent joint declaration by leading imams and the Vatican strongly urging the media to “treat religions with respect.”

That may seem reasonable and civilized, but in our particular historical-political context, such respect, normally to be encouraged and embraced, presents a threat to both reason and civilization. Conscious of the secular challenge to Christianity as well as to Islam, but fully realizing that a robust defense of freedom of expression (in practice rather than mere theory) virtually requires secularists to risk insulting Muslims, Pope Francis insists that religion must invariably be treated with respect. Like Timothy Garton Ash, I attribute the self-censorship seen in most media around the world less to a decent respect for the faith of others than to fear of violent retaliation. Despite the polarization it simultaneously reflects and intensifies, my own position, succinctly stated, comes down to this: a conviction that it’s precisely the threat of terrorism that makes it incumbent on the West to refuse to sacrifice its deepest value, freedom, to uncritically “respecting” religion—especially when the particular religion in question seeks to blackmail the rest of the world into “respecting” (under some “only-to-be-expected” threat of death) its own ban on images of the Prophet. That prohibition derives, by the way, not from the Qur’an, but from the Hadith, posthumous tales of Muhammad’s life. Ironically enough, Muslim scholars often cite a passage in the Hebrew Bible in which Abraham (whose father, Terah, was a manufacturer of idols) declares the worship of “images” a manifest “error.” The further irony is that the Islamic ban, intended to discourage the worship of idols, has turned the prohibited images, these absent presences, into another and potentially lethal form of idolatry.

.

3

Current Muslim resentment and, in its most toxic form, Islamist terrorism, have been fueled by Western colonialism and, more recently, by U. S. military intervention in the Middle East. The colonialist legacy has been, for the most part, unambiguously negative, culturally and politically. In economic terms, the victims of colonialism had imposed upon them an imported labor market management model that encouraged a race to the bottom in pursuit of comparative advantage in cheap labor. Through conquest, and with the strokes of various pens, Western colonialism created states that were less “nations” than multi-cultural entities, subject to authoritarian despots in varying degrees initially subservient to Western interests: kings and shahs and presidents-for-life propped up by the oil-thirsty West, and who, even when they asserted their independence, tended to brutally oppress their own people. In several Middle Eastern states, people ripe for revolution rose up in the exhilarating but tragically short-lived Arab Spring. That revolution, like so many others (notably including the great French Revolution itself), consumed its own idealistic children, and what emerged, or re-emerged, was military dictatorship, Islamic extremism, and another wave of emigration from North Africa and the Middle East to Europe. And some of those immigrants, especially but not only in France, became a fifth column: poor, unassimilated, embittered, and therefore susceptible to the siren call to jihad. From their ranks came the killers who lashed out at the “blasphemous” cartoonists in Paris.

In a Le Moyne College open discussion of the attack on Charlie Hebdo, four faculty presenters explored “issues behind and exposed by the murders,” murders “no one could accept.” As the organizer, history professor Bruce Erickson, rightly insisted: “we do not defend the terrorists, or justify the murderers, or reject the Enlightenment, if we ask questions about how to integrate the multi-cultural world and nations that we created through colonialism.” Though most Muslim immigrants to the United States have assimilated well, many living in France and other Western European countries have not, some choosing to self-segregate. Though the “no-go zones,” alleged Muslim enclaves governing themselves under Sharia law, turned out to be a myth, subsequently recanted by its perpetuators at Fox News, this hardly diminishes the problem, nor does it sever the connection between the colonialist past and the terrorist present. The French failure to integrate the children and grandchildren of immigrants generated just the sort of recruits who became the murderers who attacked the offices of Charlie Hebdo.

As an explanation of Islamic radicalism, these recent colonial developments, though crucial, may be more symptomatic than causal. The deep roots of jihad (whether interpreted as internal struggle or as external battle against the infidel) are to be found in the “sword-passages” of the Qur’an; and the historical expansion of Islamic extremism came with the transformation of large elements of a once relatively open and intellectually dynamic faith, the Islam of the Golden Age, into puritanical sects—primarily but not exclusively Wahhabism. That, of course, is the narrow-minded brand of Islam (a main source as well of much of the treatment of women and gays deplored in the West) globally disseminated through madrassas funded primarily by our “moderate” friend and supposed ally in the region, oil-rich Saudi Arabia.

To trace Islamic radicalization exclusively to Western provocations would be to “infantilize” Muslims, to hold them utterly blameless for their own actions. In saying that past European colonialism and more recent U.S. intervention have “fueled” Muslim resentment, my point (to flesh out the metaphor) is that these Western phenomena have fed, fanned, and intensified the flames of radicalization and reactionary terrorism. Hardly a complete explanation, let alone an excuse, for Islamist extremism, the impact of this history seems incontrovertible. I have already referred to the cumulative, corrosive legacy of the old colonialism; but here are examples of obvious Islamic reaction to Western provocations.

The original Muslim Brotherhood was reacting to colonialist secularization in Egypt. The Iranian theocracy established in 1979 by the Ayatollah Khomeini sealed the revolution against the secularist Shah, installed in 1953, after the coup against the legitimately-elected Mossadegh government: a coup engineered by petroleum-protecting British Intelligence, and orchestrated with a reluctant but still complicit American CIA. Osama bin Laden founded al Qaeda in reaction to the presence of U. S. troops in “holy” Arabia in preparation for the first (for many of us, the “justifiable”) Gulf War. And over the past decade and a half thousands of jihadists have specifically attributed their radicalization to U.S actions, whether in actual conflict and the carrying out of drone strikes, or in response to the pointless atrocities of Abu Ghraib and to the more systematic employment of torture in CIA “black sites.” The al Qaeda terrorist attacks of 9/11 preceded the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, but came after our first Gulf War. And jihadism intensified and metastasized in the wake of our duplicitous, inept, and counterproductive 2003 invasion and subsequent occupation of Iraq. Donald Rumsfeld has proven to be prophetic. In one of his myriad “snowflake” memos, the then Secretary of Defense feared that we “might generate more terrorists than we could kill.”

Given the role of the West in, not creating, but certainly exacerbating, Islamic extremism, it is worth noting that the ban on images of the Prophet intensified during the early period of European colonization when Muslims were most anxious to differentiate their religion from “image-worshiping” Christianity. The prohibition is particularly stressed by Saudi Wahhabism and Iran’s clerical theocracy. Because of the impact of these most puritanical forms of Islam, what is for most Muslims anti-iconic “respect” becomes, for many of us in the West, an idiosyncratic, irrational, regressive, and intolerant shibboleth regarding “images of the Prophet.” And yet it is a ban we are to “respect,” not on the moral grounds of sensitivity to the beliefs of others, but under compulsion: the “assassin’s veto,” the clear and present danger of retribution, including fatwa and death.

Many, probably most, Christians, Jews, Buddhists, and Hindus wish to be respectful of the beliefs of others and tolerant of difference. When the stakes are as high as they are now, however, this misplaced “tolerance” gives at least the appearance of justifying ignorance and barbarism by labeling religion’s satirists disrespectful, for some, blasphemous. With the advent of contemporary Islamist extremism, the old tensions between the religious and the secular and between freedom and limitation of expression have taken on a new urgency, becoming, literally, matters of life and death. Making fun of faith can put you in the grave.

The pope’s point about predictable retaliation, given the history of the past few decades, is non-controversial. But instead of stating the obvious, that some sort of reaction was “to be expected,” he ought to have questioned how things have come to this pass. Such a discussion would have included the background (Western colonialism), but should also have made it clear that, whatever the oppressive historical circumstances in which it evolved and to which it is reacting, Islamist extremism in its current militant form deserves to be criticized, and needs to be resisted. However flawed the West may be, civilization is preferable to barbarism.

Of course, resisting religious extremism can produce, as unthinking backlash, its own form of religious extremism. To shift from the charge that criticism of religion is “blasphemous,” consider the following manifestation of religious fanaticism, this time Christian, from a Fox News radio host and Fox News TV “contributor.” In recently attacking critics of the box-office blockbuster American Sniper, dramatizing the 160-kill exploits of sharpshooter Chris Kyle in Iraq, Todd Starnes announced that “Jesus would love” the film and would personally thank snipers for dispatching “godless” Muslims to the “lake of fire.”[1]

Far from invoking Jesus to justify violence against Muslims, Pope Francis called for “respect” toward Islam, and, indeed, all religions. In defending religion, theirs and others, from criticism, some Christian and Jewish leaders have invoked the specter of “blasphemy.” To his credit, as earlier mentioned, Francis did not employ that incendiary term, and he was right to refrain. Rather than join them in leveling the charge, we should leave such labeling to the thoughtless defenders of their particular faith, to God-and-country jingoists and to Islamist fanatics.

‘

4

It’s not necessary to applaud the often scurrilous Charlie Hebdo cartoons in order to defend the cartoonists’ freedom of expression. Unlike American satire (aside from two of its greatest practitioners, Mark Twain and H. L. Mencken), French satire has a long history of being anti-religious and anti-clerical, as well as being offensive—savagely and equally—across the board, skewering every sacred cow in sight. French satire, like the French state itself, is fiercely secular, as is most of post-World War II Western Europe. This is precisely why the previous pope, the conservative Benedict XVI, was so determined to re-Christianize Western Europe. And this is why the French people and their leaders came out in such numbers in the immediate aftermath of the lethal assault on Charlie Hebdo. Aside from expressing outrage against these particular religiously-inspired murders and this specific assault on free speech, the French marchers were defending their twin, and notably secular, heritages: the Enlightenment and the Revolution—at least the Idea of the Revolution, stain-free, the bloody guillotines of the Jacobin Terror conveniently repressed.

But despite the heartening response in the streets of Paris and elsewhere, rallying in support of Charlie Hebdo (like many others, I wondered where President Obama was, or at least Biden or Kerry), the Islamists have already won to the extent that almost everybody else in the world was, at least initially, too “terrified” to even reproduce the Charlie Muhammad cartoons—just as they were too afraid of violent retaliation to reproduce the famous “Danish cartoons” in 2005. And thereby hangs a cautionary tale about the threat of lethal violence. Though many Danish papers republished the Charlie Hebdo images, they were, significantly, not reproduced in Jyllands-Posten, where the original “Danish cartoons” had appeared. Citing the paper’s “unique position,” and concerned for employees’ safety, the paper’s foreign editor, Flemmings Rose—hardly a coward, indeed, the very man who had commissioned those Muhammad cartoons a decade earlier—candidly admitted to the BBC: “We caved in,” adding that “Violence works,” and that “sometimes the sword is mightier than the pen.” One understands his caution, and the dangerous alternative. But there is an even greater danger in surrendering the pen to the sword. Islamists, whose preferred method of terrifying infidels and recruiting fresh jihadists is the publicly exhibited decapitation of prisoners (or, most recently, burning them alive), may, paradoxically, have made it necessary to be religiously offensive in order to defend the Western concept of freedom, now faced with a challenge as theocratic as it is political.

Not showing the Charlie Hebdo cartoons, or labeling them offensive, insulting, or, worse yet, “blasphemous,” is no longer simply a matter of “good taste” or “respect for others.” In the context of a growing threat by Islamist extremists—ranging from self-appointed jihadists to organized armed forces aiming to establish by the sword a new Islamic caliphate—such normally laudable sensitivity becomes, instead, a caving-in to intimidation by fanatics. The momentarily most ruthless of them (ISIS or ISIL) is determined, in God’s name (Allahu akbar!), not only to forcibly install an “Islamic State” in the heart of the Middle East, but to repeal the Enlightenment and the modern world.

.

5

One can make nuanced arguments against both the Enlightenment and modernity, but NOT when the alternatives are irrationality, atavism, and—for unbelieving secularists—superstition. In the end, in the view of skeptics, the leaders of organized religions, Francis included, are in the business of defending their vested interests, their own particular accumulations of doctrine, tradition, and (for agnostics and atheists) “superstition.” But believers who are not fanatics have a particular responsibility to be unequivocal in condemning religious fanaticism.

No one in the world is better positioned to do so than this deservedly popular pope. The emphases and values that dominate his papacy were forged in the 1970s. When, in 1973, Jorge Bergogli became Provincial Superior of the Jesuit order in Argentina, he distanced himself from a Catholic hierarchy that had acquiesced in the brutal repression by the military junta; intensified his compassionate and Jesuit commitment to the poor; and, while avoiding direct confrontation of the military regime, struggled (in the words of Eamon Duffy, Emeritus Professor of the History of Christianity at Cambridge) “to reconcile the demands of justice and compassion for those suffering atrocity with the need to preserve the order’s institutions and mission and to save Jesuit lives” (the later accusation that he betrayed politically radical Jesuits to the junta is baseless slander). As cardinal, he exercised the same wise leadership and again stressed compassionate concern for the poor.[2]

As pope, taking his name from Francis of Assisi (a notably humble saint cherished for his protective love of the earth and of animals, and for his ministry to the poor), the former provincial and cardinal has, true to both his Jesuit heritage and to the spirit of his chosen name, continued his own focus on the poor and wretched of the earth. In his apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, on the joy and true meaning of the gospel, he pointedly denounced, to the annoyance of many conservatives, the “economics of exclusion.” He has also emphasized the dangers to the environment presented by global climate change, and even speculated that there might be a place in heaven for animals: a charming thought of which the original Francis might approve, but which doctrinally-concerned Vatican spokesmen felt the need to quickly walk back. In his first Holy Week as pope, Francis performed the solemn Maundy Thursday foot-washing ceremony not, as usual, in the Lateran Basilica but in an institution housing young offenders. He washed and kissed the feet of a dozen prisoners, one of them (though this was, traditionally, a males-only ritual) a Muslim woman, a gesture that, as Eamon Duffy notes, “predictably scandalized the liturgists and canon lawyers.”

As practiced by this pope, the imitatio Christi, following the example of Jesus, differs from the emphasis of sin-obsessed Augustine, and even from the focus on the interior life and withdrawal from the world of Thomas à Kempis in his 15th-century devotional book Imitatio Christi. This Francis follows his namesake, stressing the path of Jesus, born in a manger, preaching to the poor, practicing humility. Unlike his two immediate predecessors, who tended to treat opposition as “dissent,” Francis has been humble and conciliar in conducting meetings, encouraging a frank expression of views. In opening the Synod on the Family in October 2014, he told the bishops that, in discussing what were certain to be controversial issues, no one should be silent or conceal his true opinion, “perhaps believing that the Pope might think something else.” During the papacies of John Paul II and Benedict XVI, deviation from the official line had courted reprimand, even removal. Thus, as Eamon Duffy emphasizes: “For a pope to encourage fearless public outspokenness among the bishops was a startling novelty.” [3]

Given that attitude, one might have expected, if not quite “encouragement,” at least greater “respect” for the “fearless public outspokenness” exhibited by the massacred Charlie Hebdo cartoonists. At the very least, the pope, a remarkably empathetic man pastorally sensitive to suffering, might have displayed greater tact by mourning the dead a bit longer, before admonishing us, with the bodies not yet buried, to always “respect” religion and never “make fun of the faith of others.”

But here, the admirable Francis fell short. At least as viewed from the perspective of a secularist committed to virtually uninhibited freedom of expression—not least when it comes to religion. But that is not the only perspective, and not—as is hardly necessary to add—one shared by Francis. As pope, he is necessarily a man to double business bound, at once a condemner of violence and a defender of religion—any religion, since, in his view, none deserves to be insulted. That includes, of course, his own religion. Just as he had protected the Argentinian Jesuits in his care in the 1970s, so it is his duty now, though a reformer critical of some of its salient shortcomings, to protect the church as a whole.

On that papal plane, in responding to the Charlie Hebdo cartoons and to the retaliatory murders that followed, Francis was talking common sense, decency, civility, and mutual respect. That’s all to the good. In a chaotic world of already inflamed religious-political passions, his intention was obviously to condemn the murders in Paris without adding fuel to the fire. But his equanimity was not altogether disinterested. In asserting his own ban—“You cannot make fun of the faith of others”—the pope was also defending the Company Store: the Roman Catholic branch of a global theological enterprise. In that sense, and to that extent, he was aligning himself, not with the massacred humorists, but with their murderers: fanatics who had killed the cartoonists precisely for “making fun” of the fanatics’ own distorted version of Islam.

Like politics, theology can make strange bedfellows. But far more than this momentary convergence of interests would be required to bridge the moral abyss stretching between Pope Francis and murderers. That would be especially true of murderers who violate his own deeply-held conviction that “to kill in the name of God is an absurdity. ” For him, what happened in Paris was the commission of a supposedly religious act that is, in fact, an “aberration” of the religion and of most of the teachings of the Prophet in whose name they claim to act.

Acknowledgment

Though I learned from the previously-mentioned Le Moyne open forum on the roots of, and responses to, the Charlie Ebdo murders, this essay was originally generated by a casual but serious email exchange with three friends, all Le Moyne graduates: Scott, Jack, and Markus. Some reservations of the latter about the initial draft were incorporated in the revised version. My thanks: to Jack in general, and, on this particular occasion, to Scott, for sending along the AP item that started us off. I’m particularly grateful to Markus, for critically reading the first draft and helping to sharpen and clarify my thoughts, not all of which he will endorse. The same is true of Bruce Erickson, the organizer of the Le Moyne forum, who, along with the four faculty presenters, enriched my understanding. Bruce also responded to my penultimate draft, thoughtfully, graciously, and productively challenging my position.

—Patrick J. Keane

January/ February 2015

.

Patrick J. Keane is Professor Emeritus of Le Moyne College. Though he has written on a wide range of topics, his areas of special interest have been 19th and 20th-century poetry in the Romantic tradition; Irish literature and history; the interactions of literature with philosophic, religious, and political thinking; the impact of Nietzsche on certain 20th century writers; and, most recently, Transatlantic studies, exploring the influence of German Idealist philosophy and British Romanticism on American writers. His books include William Butler Yeats: Contemporary Studies in Literature (1973), A Wild Civility: Interactions in the Poetry and Thought of Robert Graves (1980), Yeats’s Interactions with Tradition (1987), Terrible Beauty: Yeats, Joyce, Ireland and the Myth of the Devouring Female (1988), Coleridge’s Submerged Politics (1994), Emerson, Romanticism, and Intuitive Reason: The Transatlantic “Light of All Our Day” (2003), and Emily Dickinson’s Approving God: Divine Design and the Problem of Suffering (2007).

.

.