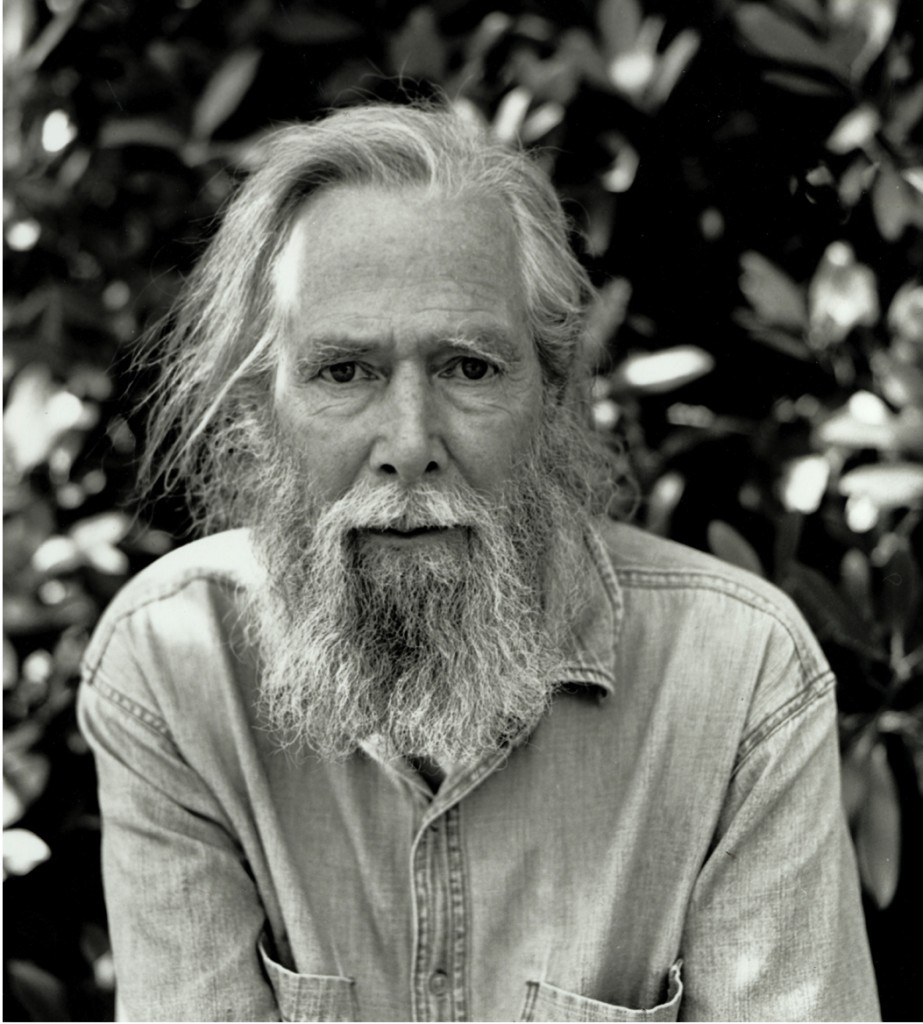

Photo by Nancy Marshall

Photo by Nancy Marshall

.

Sam Savage was born in Camden, South Carolina, on 9 November 1940, the fifth of seven children of Henry Savage, Jr., and Elizabeth Jones Savage. Henry was, to quote the author, “a polymath: lawyer, architect, civic leader, historian, naturalist, and author of several books of history, biography, and natural history,” while Elizabeth’s tastes “were more literary. She was well-read to an exceptional degree.” Savage exhibits a combination of these skills. Though not entering school until age seven, as discussed below, he attended the University of Heidelberg and Yale, graduating from the latter with a degree in philosophy.

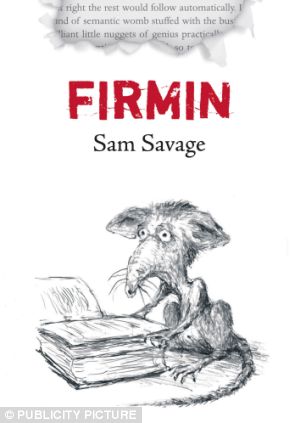

For much of his adult life Savage has written poetry and fiction, publishing intermittently from the age of twenty, but not finding his true voice until late in life. In 2005 his first book appeared, The Criminal Life of Effie O., a novel in verse that Savage considers an “amusement.” His career as a fiction writer changed with the publication the next year of Firmin: Adventures of a Metropolitan Lowlife (2006), a first-person narrative told by Firmin, a male rat that can read. The Cry of the Sloth (2009), an epistolary novel, features every word, right down to grocery lists, written over the course of three months by Andrew Whittaker, minor writer and small-time slum lord. In 2011 came Glass, a first-person set of reminiscences by Edna, who spends her days typing. The Way of the Dog (2013) is a set of reflections by a male narrator named Harold Nivenson, who observes things out the living room window of his home and recalls his former activity within the art world. Savage’s most recent novel is It Will End with Us (2014), a collection of connected memories put down by Eve as she recalls her Southern childhood. All works except the first have been published by Coffee House Press.

This interview was conducted in February and March 2015 via email. My thanks go to Sam Savage for his patience.

* * * *

Early life and education

Jeff Bursey (JB): Perhaps we could begin with something about your family. What kind of people were they? What did you think of them when growing up, and what do you think of them now?

Sam Savage (SS): Both sides of the family have roots in America going back to the mid-1600s, my mother’s side in Virginia, my father’s in Massachusetts. My father owned large tracts of timberland. We were local gentry of sorts. My father was probably the town’s most prominent and certainly its most admired citizen.

What did/do I think of them? My parents were kind, upright, generous people, utterly devoted to their children. In manners they presented a seamless blend of Yankee restraint and Southern courtesy.

JB: What religion were you raised in?

SS: I attended the Episcopal Church until I was about twelve, when I lost faith in the existence of God.

JB: You had a period of rebellion in your teens, the kind that comes upon many. What were you rebelling against, and what form did that take?

SS: Against everything and nothing—mindless encompassing anger, a condition of such unrestraint that parents would not let their sons and daughters get in the car with me for fear I would entangle them in some catastrophe. It’s a miracle I got out of that alive.

JB: What does it mean for you to consider it a “miracle” you got out of your teens alive?

SS: My teenage years were marked by extremes of recklessness that I can scarcely compass today. The “miracle” is that they did not end with prison or death by automobile.

JB: If we can stay with this for a moment, I’d like to know how you mean the word “miracle” to be taken. It’s a charged religious term, and readers of your work know you are quite often exact, even when being ambiguous. Does it have a particular meaning for you?

SS: I just meant the odds were long.

JB: In The Way of the Dog, your lead character, Harold Nivenson, says: “By the time I was eighteen I was already practically insane. By the time I was twenty I was already completely crazy. I must have been crazy for a long time before that, perhaps from birth.” That sounds like your own experience.

SS: Well, the manner in which we were crazy was different.

JB: With reference to your parents’ manners of restraint and courtesy, where did the “mindless encompassing anger” come from, and where did it go? Were you antagonistic towards those manners? Did these feelings flare up from nowhere and burn out as mysteriously?

SS: I was intensely loyal to my family. No rebellion there. On the contrary, I experienced the house as a place of calm and refuge. Leaving the South lifted a great weight off me, in Boston first, then New York, then France. With each move I felt freer.

JB: Anyone reading your books would know that most of the main characters are simmering with anger, fear, resentment and other emotions, but the narrative only provides brief glimpses of their past. That repression coupled with the at times unhinged nature of Edna or Andrew—their manias, if that’s not an inapt word, shown more than their genesis—creates a lot of the energy and power found in your novels. Do their states owe anything to the intense feelings you had?

SS: I don’t suppose I could ascribe to my characters emotions or states of mind that I had never experienced, but the fact remains that the lives of these characters bear little resemblance to my own.

JB: You speak of losing faith at age 12. In his The Life of Ezra Pound, Noel Stock says one of Pound’s uncles “inclined towards the Episcopal Church because it interfered ‘neither with a man’s politics nor his religion.’” I read that Darwin was a favourite of your father’s. The dearth of any Supreme Mover or Higher Power or God, however one wants to phrase it, is noticeable in your books. In a review of Glass I suggested this: “One wonders if Sam Savage is indicating that we live in a Godless universe, with Edna just one more creature in a glass cage, unloved and not made to last. If so, then this is a chilling picture of old age and contemporary society.” Up to the loss of faith you mentioned, did you feel a tug between science and religion, or was there something more intimate going on?

SS: My answer to your earlier question about religion ought to have been more nuanced. I never had “faith” in any real sense. I attended church with my family when I was quite young, but I never gave two thoughts to what was said there. My first encounter with God was with an absence. I suppose the problem, put crudely, is that I have in the course of life developed a religious sensibility and a scientific mind – a problematic combination. Though I don’t explicitly talk about it, the absence of God is, I think, a presence in all my books, like a shadow falling over them.

JB: That combination—how do you see that working itself out in your life and fiction?

SS: The characters in the novels are searching for meaning in the world and in their lives. I regret if that sounds terribly old-school and cliché. Meaning is not something you can invent, something you can freely choose. If you can choose it you can unchoose it just as easily. It has come from without in some sense. It has to make a claim upon you. Nothing I have seen in the world as I understand it (the natural-scientific world) is capable of making such a claim, and all my protagonists experience that.

JB: It doesn’t sound old-school to me. I would ask where you think meaning resides when you say it “has come from without…”

SS: I mean it has to come from beyond and be independent of our ratiocination and whim. Meaning is something you discover. It is something you experience, not something you can just make up. Where it resides now I have no idea. For a large segment of Western culture there was a general collapse of meaning, a disenchantment and desacralization of the world, between Darwin and the end of the First World War. Modernism in literature and art can be seen as a response to this, an attempt to reckon with the new reality.

JB: Where did the first years of your education take place, what type was it, was it satisfactory, and were there particular teachers you got something from or who saw something in you?

SS: I hated school from the moment I stepped through the schoolhouse door when I was seven. I hated the teachers, the books, the building. I was in and out, refusing to go and (when sent to boarding school) running away. I was twenty when I finally graduated from high school. Except for a smattering of mathematics, everything useful I had learned by that time I had taught myself or absorbed by osmosis from my family. I went to Yale (admitted on the strength of SATs), disliked it there, and dropped out after three months. I returned five years later, finished the undergraduate program in three years, graduating in 1968.

JB: Were your feelings about school, at age seven and a little more, understood or tolerated by your parents, even as, I assume, they insisted you keep attending?

SS: The Savage family did not have harmonious relations with schools. Some of my siblings had relations nearly as stormy as my own. My parents understood perfectly that the fault lay in the stupidity and unconscious petty brutality of the schools and not with their children, who wanted nothing better than to be encouraged to learn in their own way. They did not insist that we continue, once they had grasped what torture it was for us.

I started at seven because the school was overcrowded and there was no room for me the previous year. I had attended a total of seven schools by the time I graduated, and I had gone one year without attending school at all. For most of that epoch I was more interested in cars than books. I wasn’t made to feel peculiar. I always had friends. I think some people thought I was crazy, but that didn’t bother me. I was thoroughly miserable through most of my teenage years, but not more so than a lot of other people at that age. Given a time machine, it is not a period of my life that I would willingly visit.

The 1950s were an awful time—oppressive, violent, hypocritical, frightened, and suffocating, doubly so in the deep South. I don’t know if a decade can kill a man, but the 1950s came close to killing me, I think Norman Mailer remarked somewhere. I wasn’t quite a man yet, but it was a rotten epoch to come of age in. My wife jokes that I can’t talk about the 1950s without, as she puts it, “frothing at the mouth.”

JB: Did you know how to read before going to school at what seems a late age?

SS: I was read to, but with four older siblings I was not read to as much as I am sure my mother would have liked. I taught myself to read in the first week or so of school, and I had no use for school after that. In those first days we were drilled in the alphabet. There was a moment of insight: I suddenly saw how it all worked, how the code worked, with letters standing in for sounds. That was a Friday. My mother told me I sat in the house for two days puzzling it out. On Monday I could read.

JB: I’ve not heard of any child figuring out how to read like that. Was this something your siblings could also do?

SS: I don’t know. Understand that I wasn’t jumping into Dickens—I was just reading my first-grade books: See Spot run. See Jane run, and so forth.

JB: What did you like to read at that age?

SS: I read all sorts of things. Hardy boys of course, and endless comic books, Jules Verne, Conan Doyle, Rafael Sabatini, the historical novels of Kenneth Roberts, but also Walter Scott and Dickens. A child doesn’t read like an adult, processing language; he dreams the book. I read Ivanhoe, Rob Roy, Waverly, Quentin Durward, Great Expectations, Oliver Twist, A Tale of Two Cities, completely untroubled by the hundreds of words I didn’t know, sailing right over them. I would give anything to be able to read like that again.

JB: The words you didn’t understand in those books you read as a child, did you ever look them up?

SS: I don’t think so. I don’t remember making use of a dictionary as a child. I remember that my oldest sister, four years older than me, spent a long time memorizing Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, so she wouldn’t have to bother looking up words anymore. I remember being terribly impressed by that. I must have been eleven or twelve when she was doing that.

JB: You say: “everything useful I had learned by that time I had taught myself or absorbed by osmosis from my family.” What were those things? And do you mean useful for you alone or useful for anyone?

SS: I mean useful to me as a writer—the capacity to recognize a good sentence, a fondness for clarity and wit, a boundless admiration for artistic achievement and its corollary: sympathy for those who strive and fail.

JB: Your phrase about how a child “dreams the book” brings two things to mind. First, in Henry Miller’s The Books in My Life, he talks about “the physical ambiance of the occasion,” and the feel of the book, the smell of the pages. In that book Miller also says he’d love to have a library of the books he read from childhood to becoming a young man, which seems to echo your thoughts.

SS: I have had feelings like Miller’s. I used to love buying new books. I loved having them in the bookcase. These days not so much. I use the public library when I can, except for books by living authors. Those I always buy: I don’t like depriving an author of his or her meager pittance. I got rid of almost all my books a dozen years ago, thousands of volumes, but now they are piling up again. As Edna remarks, books are rather unsanitary objects. They collect dust easily, have a tendency to mold, and are among the rare personal items that cannot be washed.

Sam and Son, 1982

Sam and Son, 1982

JB: Second, that phrase would seem to encapsulate the form of your narratives as spun out by your characters: they write letters, memoirs, notes, and impressions, on typewriters and by hand, all in an effort to reach some imagined or real Other. Though it might be more accurate to say they nightmare the book.

SS: I don’t see the narratives as dreamlike except maybe in the way they are not governed by any overarching schema, in the way the narrative wanders down a path that has no goal or preset destination, where paragraph 38 is there because paragraph 37 is there, or maybe for no reason at all, because it popped up in the narrator’s head at just that moment.

JB: Before talking further about your books, can you describe in a bit more detail your time at university, and your studies? Were there any professors you recall fondly or otherwise? What kind of philosophy did you prefer studying, and has that interest changed over time?

SS: In September 1960 I entered Yale the first time, disliked it there and dropped out after three months. I went to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for spring semester 1961 and dropped out. I went to New York at the beginning of 1962, left for France in early 1963, and returned to Yale in the fall of 1965. I don’t remember the name or face of a single classmate from those years.

I was at the University of Heidelberg for three semesters in 1970-1971 while still in graduate school at Yale. I did not take a degree there. I went to Heidelberg to study philosophy and improve my German, and because Hans-Georg Gadamer, a prominent post-Heideggerian, was a professor there. Two professors at Yale had a strong effect on my thinking then, and even today to some extent: Karsten Harries, who taught Heidegger, and Robert Fogelin, who taught Wittgenstein.

Two hours after defending my doctoral thesis (on the political thought of Thomas Hobbes) at Yale I was on a train to Boston. I have never been back.

Career

JB: Though you left Yale quickly after the defense, while you were a student did you imagine a career as a philosophy professor or as a philosopher? What kind of philosophy did you prefer?

SS: I spent most of my time on German philosophy, Kant to Heidegger. But also classical Greek philosophy and Wittgenstein. In my final year as an undergraduate I was named “Scholar of the House,” which meant that I was exempted from course work that year and allowed to spend all my time on a thesis, rather like a Master’s program. I wrote my thesis on Nietzsche. I also taught Nietzsche at Yale during the three semesters I was hired as what they called an Acting Instructor, which meant basically a full-time teacher who was paid very little. I also taught an introduction to ethics and a course on Marx.

I enjoyed teaching, but I never wanted a university career. I finished graduate school in 1972, taught for a while, as I said, and got my Ph.D. in 1979. In the years between 1973 and 1978 I was living in France and making fitful stabs at writing fiction, actually imagining myself as a writer but not accomplishing anything, and at the same time doing nothing to advance my doctoral studies. In 1978 I decided to complete the doctorate, for no good reason, just so as not to have another abandoned project on my conscience. It took me six months to research and write the thesis. It was a fine, almost intoxicating feeling, to be through with the academic world for good. I went back home to South Carolina, to a little town of 400 souls, stayed there for the next twenty-three years, raised two children, and wrote doggedly, living all the while on my small income, occasional jobs, and the labors of my wife.

JB: On the academic world. Harold Nivenson says: “The university as presently constituted… is a death-trap for the mind, I have long thought.” Does that come close to your own beliefs?

SS: Yes.

JB: What about being employed, at odd jobs or more regular work, in childhood, as a student, or later?

SS: I never held after-school or summer jobs while growing up. My mother thought it wrong for the children of more affluent families to take summer jobs that would otherwise go to those who needed them more. She was right of course. I later worked at several jobs intermittently over the years, none for very long, except for those few years teaching, first as a teaching assistant and then as acting instructor.

It is important to note here that I always had a small inherited income, not enough to live on easily, but enough to keep me free of the economic restraints that drive many people into careers they dislike. I was fortunate in being naturally handy, I actually enjoyed physical labor of the less grueling sort, and neither I nor Nora minded living on little. People like to talk about the unusual jobs I have held, but some of those were actually of no importance, more like pastimes than work.

JB: Apart from studying, and writing, was there something enjoyable outside academia? Theater, museums, films, or travel, for instance. Or was it all work?

SS: Films, of course, especially those of the Nouvelle Vague, and I was crazy about ballet, used to sit all night on the sidewalk for a ticket to see Nureyev dance. Besides getting a degree, I read a lot of philosophy at the university. I am at a loss to say how or to what degree that immersion in philosophy has affected my writing.

JB: What did you like about ballet, and is that still an interest?

SS: I still love ballet. I love the brave and futile challenge to gravity and to the burden of a human body. Witnessing a fine ballet is for me like watching angels taxiing for takeoff.

JB: Do you go to live ballet performances now? How has that art changed, in your opinion, since you first started going?

SS: Every year, when we lived in South Carolina, Nora and I would attend the ballet performances at the Spoleto Festival in Charleston. Sometimes a decent dance company shows up in Madison, but I am not able to go anymore. With such sporadic attendance I am not in a position to comment on the evolution of the art.

JB: What did you take away from time in France and Germany?

SS: From Germany, mostly a little better understanding of the polyvalence of history and a lot better grasp of spoken German, which I have, alas, almost entirely lost in the decades since. France is different. I have always felt most at home there. I lived in France for a total of over eight years. Many of my closest friends have been French. I was married to a French woman for seven years. I have a son who was raised in France. Nora Manheim, mother of my two other children, who has stuck by me for forty years now, is an American who grew up entirely in France, daughter of expatriates there. I haven’t been back in a long time.

JB: You mentioned having friends when in school but not remembering anyone from university. Was socializing with classmates not important, or did whoever you meet at that time simply fall out of your life once you were done with the institution?

SS: You have to understand. I was 25 years old, I had been around, and now I was once again a freshman at an all-male institution that was, socially, indistinguishable from an elite New England prep school. Most of the students lived on another planet from me. Furthermore I was married and father of a child. I lived off-campus, something no other undergraduate students did at that time. I am talking about undergraduate years. I do remember some of my fellow students in graduate school, though I haven’t kept in touch with any of them.

JB: I understand you would like to leave some matters alone, so we can move on. What was the appeal of South Carolina? Where did you move after that, and why?

SS: It was a place where, after so many years, I found I was comfortable again. It was still unjust in many ways, but the violence was mostly gone and you could see progress every day, something that was hardly the case in the rest of the country. I like to sit with Southerners and talk. They still tell the best stories. I love the swamps and marshes. My wife and I, with the help of friends, built a house in the woods there. I would be there still if I could. We moved to Madison twelve years ago. We moved because we have a disabled daughter, and this is a better place for her than isolated among the pine trees in South Carolina.

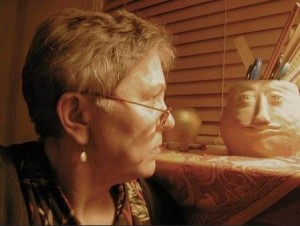

Sam and Nora, Madison, Wisconsin, 2013

Sam and Nora, Madison, Wisconsin, 2013

JB: What is life like in Madison? Are there storytellers there, like in South Carolina?

SS: Life in Madison? I work. I used to take walks in the neighborhood. Now I look out the window. In the warmer seasons Nora and I go out to lunch once or twice a week. My sons come for long visits every year. Friends come from South Carolina and from France. I don’t know anybody in Madison apart from neighbors, a couple of Nora’s friends, and doctors. I can hardly be said to live here. I feel I am just passing through, practically unobserved, like a ghost.

Health and writing

JB: In the 1970s you learned you had alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. What is that, in your own words?

SS: I am missing a blood component that protects the lungs from attack by some of the body’s own enzymes. The consequences vary widely. Chief among the more serious are liver failure and lung destruction in the form or early onset emphysema. I noticed breathing problems before I was thirty, but assumed it was asthma. It’s an ineluctable, irreversible process.

JB: Does your health feed into your fiction?

SS: It must, though I am hard put to say how. Illness is a world of its own. Everything is colored by it. I have outlived my prognosis by many years, but for decades the illness would not let me contemplate a “normal” life stretching into a vague and distant future. All my narrators are, one way or the other, in the process of dying.

JB: When you say you have “outlived your prognosis,” I think of the tenacity of certain characters in your novels, but it’s of a kind that comes from the most basic instinct for survival. No one in your books, human animals or non-human animals, to use a current distinction, lives well. As you say, they’re “in the process of dying.” Do you explore the extinguishing of life with your own health in mind because it’s a topic of interest, to have a conversation with yourself, to communicate something that can’t come out any other way, or for other reasons?

SS: Had I been in booming health, I might have written differently, I suppose, though there are also reasons to think otherwise. There was a long period, in my twenties and early thirties, before I became really noticeably sick, when awareness of death in the form of a boundless encompassing dread was so persistent and unbearable that I contemplated suicide in order to escape it. I thought: better die now than experience this dread every day, possibly for decades, and still die in the end. I am constantly amazed that not everyone seems to feel this. I suspect a cover-up. Maybe a genetically based survival mechanism that lets us be deliberately stupid in this regard, so we can get on with our lives as if nothing were amiss. Bad faith on a planetary scale. Maybe being sick—and during the last twenty years quite obviously so—has made me more sensitive to the blitheness with which we normally—and I suppose I can say mercifully—go about the business of living. But there is such a thing as truth in fiction. A novel, if it is any good, ought to let us see the lies we tell ourselves. It is not a novelist’s job to be merciful.

JB: That dread of death ended before you became sick. Obviously it never felt so overwhelming as to make you commit suicide. What kept you alive? And did the dread taper off or end because you became sick?

SS: What keeps anybody alive? Love, distraction, I suppose, and, above all, an unwillingness to do that to my children.

JB: Kjersti A. Skomsvold is the author of The Faster I Walk, the Smaller I Am. She had been diagnosed with an illness, and went home to her parents’ basement to die. There she began to write that novel. At a PEN event she gave a talk in which she said: “I was very lonely those years, and scared. When I was lying there, looking up at the ceiling, I started to think about death. I wonder if the inevitable loneliness of being human is due to the fact that when we die, we die alone.” That seems to be one of the merciless truths your novels explore, especially in Firmin and The Cry of the Sloth, but being alone is present in the other works too.

SS: We die alone, of course. No one can die my death for me. The awareness of death throws us back into the essential solitude of the self as nothing else can. We are talking now about something more fundamental than loneliness, which can be relieved by other people. We are talking about aloneness, that state in which we are genuinely ourselves and not anyone else, when the social world with its myriad deceptions has fallen away. All my protagonists dwell, each in his or her own way, in that aloneness.

JB: “All my protagonists dwell, each in his or her own way, in that aloneness.” With your health the way it is, and the early dread of dying, would you say that your awareness of aloneness is given to these characters or is it impossible to write them without that as a precondition?

SS: I think one can write about all sorts of things one has not experienced. I imagine that with enough research I could set a fairly credible novel in prison or in Moscow. But I doubt the same is true of states of consciousness.

Publication

JB: When did you start writing, and what did you start with? When did you start writing for publication? What sort of reception did it have? I know in Poets & Writers you stated there were only a few poems published and that you stopped writing at age 55. Had writing, as an activity, pleased you up to a certain point and then, due to not being accepted, ceased to be that? What had it become by the time you stopped?

SS: I was eighteen when I first imagined becoming a writer. By the time I dropped out of college at twenty I saw writing as what I essentially did, everything else being ancillary to that. And so it has been ever since except for the five or six years I was obsessed with philosophy. I wrote a great deal, mostly poetry, but fragments of novels as well, and disliked what I wrote, and threw it out. I was not discouraged by rejections. I submitted rarely, was accepted as often as I could expect. It was not a rewarding thing to do, publishing poems of no interest alongside other poems of no interest in journals that nobody read. Publication has never been the goal; rejection has never been the problem. The writing I did for forty-odd years was not coming from the place that real writing comes from, and I knew that, and that was the problem. Genuine writing, writing that is true and good, is a product of compulsion. It possesses the shape and content it does because you can’t do it any other way. It took me a long time to feel that what I wrote was coming out of that kind of necessity.

JB: What happened to change things?

SS: I don’t know. One day the writing was different, and I knew it.

JB: What kinds of poetry did you write at first, and what kinds of fiction?

SS: Between the time I left Yale and the time I returned I was primarily interested in the poetry coming out of Black Mountain: Olson, Creeley, Oppenheimer, Duncan. Also W.C. Williams and the whole objectivist school, George Oppen and Charles Reznikoff in particular. And behind them all, of course, the poetry of Ezra Pound. I wrote a fair amount in a sort of objectivist vein. Nothing survives from that time. I doubt it was any good. Most of my fiction efforts in those early years were attempts to make money so I could live as a poet: unfinished crime and science-fiction novels, and even an attempt at a romance novel. That one turned rather lurid, as I recall.

JB: What appealed to you about the Objectivists and the Black Mountain poets? Has that lasted?

SS: I think it was the economy, the avoidance of cliché and worn-out rhythms, and the sparseness of the verse. I haven’t read any of them in decades. The poet I feel closest to, the one who has spoken to me in the most personal way for decades now, is John Berryman. He alone in modern literature is able to achieve a truly Shakespearian pathos.

JB: What fiction writers, beyond Williams and, I suppose, Reznikoff, did you read? Who do you read now?

SS: I am not familiar with any fiction by Williams or Reznikoff. A list of the books I have read over my many years would be exceedingly tedious. Among the modern writers who “knocked my socks off,” as Firmin liked to put it, the first time I read them would be Céline, Hamsun, Joyce, Beckett, Bernhard, Faulkner, Gaddis, Lowry. I read less now than I use to, and I read more slowly now. I don’t know much about contemporary fiction, meaning the works of writers younger than me. I reread a fair amount. Here’s what I read this past winter: I reread The Brother’s Karamazov for the third or fourth time; I read two novels and a memoire by Natalie Sarraute (The Golden Fruits, Do You Hear Them?, and Childhood), The Mussel Feast by Birgit Vanderbeke, and Henry James’s The Bostonians. Not a long list. And I notice it contains only one contemporary writer. But it is typical, probably, of my reading in recent years.

JB: Does reading inspire you to write, or make you think, “I could do something with that”? A related question: when you’re writing, do you stay away from reading certain writers or genres?

SS: I received from my parents, from their own attitudes, the gift of admiration. While reading a novel I often think how wonderful it would be to write like that. This past winter I was reading The Golden Fruits. Nora passed through the room, and I said something to the effect that this was a wonderful novel. She laughed and said, “You always say that.” I was interested to see, when David Markson’s library ended up at the Strand, that he wrote marginal comments in the novels he read, often highly critical comments, as if arguing with the author. I don’t do anything like that.

As for avoiding certain writers or genres, I stay away from books that I suspect might resemble the thing I am working on.

Sam and Nora, 1993

Sam and Nora, 1993

JB: Did you, or do you, feel part of a community of writers? Here I mean not only connected to those who you read but those who you met. Not that you felt part of a group—that would surprise me—but if you perceived that individual contemporary authors were on the same wavelength as you. If that does exist, is that shared interest—in topics, approach, what have you—important for your morale? Does it help keep you going? Or do you feel lonely as a writer?

SS: I have two writer friends, one of whom I haven’t seen in fifty years, and neither are remotely on my wavelength. Do I feel lonely as a writer? I don’t know that lonely is the word. I feel isolated.

JB: In your published novels there is often a mystery as to what’s going on, where the fault lines are in a character, how they landed where we see them, and, as mentioned, with very little history given. The reader is expected to piece things together. Is that a lingering effect—a good one, in my opinion—from trying to write crime novels?

SS: I don’t think so. If that tendency came from anywhere it was more likely from reading Faulkner and Ford Maddox Ford. You are right that I require readers to be more active and engaged than maybe most novelists do. I want to make it so readers have to participate in the creation of the story. I want them to lend their consciousness and lifeblood to the characters, so those characters can come alive inside them.

JB: What kind of science fiction did you write? And romance—I’m imagining a younger and more cheerful Eve Taggart, from It Will End with Us, in a sweltering southern city, with beaus and such.

SS: Dystopias, of course. I don’t remember my attempt at a romance novel. I only recall my judgment of the fragments I managed to produce: dishonest and second-rate, even for pulp.

JB: If publication has never been the goal, what has been, and has that goal changed over time?

SS: I once, only half facetiously, made a list of three things I wanted to accomplish in life: run a marathon, learn to play the saxophone, and write a great poem. I have failed at all three.

In fact I have always had only one goal: to write one truly good poem, or later, one truly good novel.

JB: Twenty-three years writing. What did you learn about yourself in that time? Patience, I assume.

SS: I learned that I am a certifiable lunatic who can’t quite admit the jump is too high for him to clear.

JB: What keeps you trying to make that jump?

SS: God only knows. A lot of free time, maybe, and a mulish temperament.

JB: Before getting into what these books are about, I’d like to know when the title comes to you.

SS: All the titles were chosen after the novels were written. While in progress they bore the names of their narrators: Firmin, Whittaker, Edna, Nivenson, Eve. I would like to have kept those names as the final titles, but the publisher wouldn’t have wanted to do that.

JB: I know you like Gilbert Sorrentino, whose last books were also published by Coffee House Press. He wrote in an essay called “Genetic Coding” that he has “an obsessive concern with formal structure…” Many of your works could be said to fall into the category of memoir, since we don’t get the particulars of the lives of these figures. Is this revisiting of that form, if indeed that’s what it is, on one level similar to what Sorrentino is referring to?

SS: While I admire Sorrentino, his integrity as an artist, his capacity for formal invention, and the frequent brilliance of his writing, we have almost nothing in common. He once remarked, I believe, that for him content was an extension of form. For me the opposite is true. I am, I fear, an old-fashioned realist at heart. However, looking back on it all, I can see there is a structure common to all the novels. They are, as you observed, first-person narratives, confessions really. The speaker is always confined in a dwelling of some sort (bookstore, apartment, house, etc.). All the narrators/protagonists are attempting to complete a work of some sort, and in most cases that work is the one we are reading. Another odd thing, which I am at a loss to explain: every novel has an emblematic animal: rat, sloth, rat and fish, dog, birds. In one case (Firmin) the narrator might (or might not) actually be an animal. In another he imagines himself as an animal (Sloth). In The Way of the Dog the animal becomes emblematic of acceptance and wisdom. In Glass the rat and fish are emblematic of Edna’s confinement and separation from the world (by sheets of glass). In It Will End with Us the birds are emblems of transcendence, I suppose I can say.

The novels

JB: Was The Criminal Life of Effie O. your first completed book? Is there an earlier completed manuscript in a desk drawer? How long before your work was accepted by a publishing house, and did that experience work out as you had hoped?

SS: Nothing in the desk drawer of any interest. I found a publisher (Coffee House Press) in a matter of weeks—no dramatic tale of artistic suffering and perseverance there. I have no complaints about Coffee House Press. There are obvious disadvantages to publishing with a small house, but they have never interfered in the writing itself. They have stuck by me through thick and thin (a lot of thin lately), something no commercial press would have been able to do.

Effie O. was written as an amusement, a joint project with my sister, who illustrated it. I published it only because I didn’t want her to have wasted her time on illustrations for a book that would stay in a drawer. I don’t know if it will ever be of interest to anyone. I toy with the idea of taking it out of print. It would make a good basis for a musical, though, and maybe somebody someday will find some such use for it.

JB: Are you musical?

SS: Though I love music, I have no musical talent. Unhappy lessons on the flute as a child were proof of that.

JB: Can you say something about the kinds of music you like?

SS: Classical and jazz, for the most part. And Dylan. But he’s an outlier.

JB: Particular composers or epochs? Do you go to concerts?

SS: In classical, pretty much any epoch, though I am not musician enough to enjoy some complex modern works. Most of Schoenberg, Webern, and Carter, for example, is beyond my reach. In jazz, it’s the 1950s and 1960s. Coltrane, Davis, Monk, Mingus, etc.

JB: Do you write with music playing?

SS: Never. In fact I don’t understand how some people can do that. When I write I have rhythms in my head that are impossible to hear when other rhythms are being laid on top of them.

JB: Why would you think of taking Effie O. out of print?

SS: I had hoped that the relative success of Firmin would prompt people to take a look at Effie O., but that seems not to have happened. It was not intended to be a great artwork. It was meant to entertain. If it fails to do that, I don’t see the point of it. It is like when you tell a joke and no one laughs. All you feel is embarrassment.

JB: Andrew Whittaker asks himself if his jokes “were ever funny, or did I just make them seem so by my laughter.” It’s one of the many sad comments he makes.

Could you say a little about how each book came to be?

SS: The process is always the same. I write the first paragraphs, more or less out of the blue, without knowing who is speaking or where it is going. Mostly those paragraphs go nowhere. But rarely (meaning it has happened five times) several other paragraphs follow, I catch a voice, a way of speaking and writing unique to that character. I am usually well into the novel before I get a glimpse of the shape it will take in the long run. I don’t know how it will end until I get there. Everything else in the novel gets revised or shifted about but those first paragraphs remain unchanged, almost word for word the way I wrote them.

JB: Where does the “voice” come from for the paragraphs that become novels?

SS: I have no idea. It is suddenly there. I don’t of course mean an audible voice: a way of speaking, a way of seeing the world from an angle so specific that it defines the character of the person who is viewing the world in that way.

JB: The first book of yours that I read was Firmin. That a rat—or an apparent rat, to keep your distinction in mind—could elicit sympathy is a feat of the imagination. He lives on chewing books, but also becomes literate, though he can’t speak anything other than, well, Rat. He is ostracized by his family for his astonishing abilities, and he can’t connect to the human world, represented by Pembroke Books, where he lives. He is outside everything. I assume that no one could have predicted the popularity of this book. Tell me about its reception and how it affected you.

SS: I thought the book was good, and I thought it would get a favorable reception, but I assumed this would come from a very narrow audience. If somebody had suggested the book would sell three thousand copies I would have scoffed. When it started selling in the hundreds of thousands in Europe I was flabbergasted. Flabbergasted by the numbers, of course, but also by the fact that people seemed to be reading a book I didn’t know I had written. They were encountering a lovable character, some even found him “cute” (the unkindest compliment of all), when I had meant to model him on the despicable self-loathing narrator of Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground. I thought I had a written a tragedy. I thought it was desperate book. I felt like shouting, “But that’s not what I meant, that’s not it at all.” This widespread reading was reinforced by Random House, which issued a hideous edition of the book with a big bite taken out of the cover and little mice in the margins of the pages in what I think was a deliberate effort to trivialize the novel, trivialization being, in the publishing world, widely viewed as a recipe for success. It might have been better if subsequent publishers had kept the marvelous illustrations Michael Mikolowski did for the original Coffee House Press edition, which have a much harder edge than the later ones by Fernando Krahn.

I recognize that an author’s intention is not the sole criterion for the interpretation of a work, that it is the reader’s privilege to see the novel differently from the way I meant it, but nevertheless I was thoroughly disconcerted by the discrepancy. I sometimes feel that I am not actually the author of that book that sold in those hundreds of thousands. A bystander, an innocent witness to the hoopla.

JB: Especially since in Firmin there is this line: “I despise good-natured old Ratty in The Wind in the Willows. I piss down the throats of Mickey Mouse and Stuart Little. Affable, shuffling, cute, they stick in my craw like fish bones.” That would seem warning enough to a reader not to view this as a novelty tale.

You’re surprised by how this book was received, that you meant to convey something different than what many readers came away with. Do you think people misread the book? Do you think there were themes and emotions in that novel that might have seemed minor to you, or escaped you entirely, but that were primary for other readers? I wonder if you think eisegesis was performed by many.

SS: Clearly there are themes and emotions that escaped me. Some readers found a book I didn’t know I had written, that perhaps I might not have written had I been aware of it. But in no way am I denying that I wrote it, however inadvertently.

I certainly don’t resent the success. But I do think it has probably hurt the reception of my other novels. It has given a lot of people a wrong idea of the kind of writer I am. They come to those other novels with certain expectations, and they are disappointed. And then of course they blame me for it, as if I had written a bad novel rather than a pretty good novel that was just not for them. Or they don’t come to the other novels at all, thinking that I am only the author of a funny rat story.

JB: As you said, intention is not the only criterion. Leaving aside The Confessions of Effie O. and Firmin, which of your other novels has been received and understood more like you wanted?

SS: I don’t have any complaints in the case of the last three. The reception of The Cry of the Sloth was sometimes problematic for me. People tended to pigeonhole it as a satire of the so-called literary world, which it really isn’t, at least not fundamentally. I don’t know anything about the literary world and have no interest in satirizing it. The novel was meant to be a satire of the human capacity for ambition and delusion, in whatever milieu, and a study of a certain complex self-parodying individual at war with himself and his environment.

JB: Do you stay away from the literary world?

SS: Not expressly. I am simply not part of it, have never been part of it. I don’t live in a writerly world, in Brooklyn, for example, and I am not connected to a university. When I began to publish I was already too sick to do writerly things like readings, book fairs, and so forth, where I might have encountered denizens of that world.

JB: The diction and tone, grammar and perspectives, of your novels are always very precise. In a letter to his ex-wife, Andrew says: “Even at the time of your departure at least half of them”—he’s talking about houses they own—“were white elephants or worse, and they are now so heavily mortgaged, so deteriorated, they barely suffice to keep my small raft afloat while it is being tossed about on an ocean of shit, meager as it is and weighted with the barest of necessities. (I mean to say the raft is meager; the ocean of shit is, of course, boundless.)” Edna is also careful in her language: “And I ought not to have said that the doorbell rang suddenly. After all, how else could it ring? Unless it were outfitted with some sort of crescendoing device that would let it gradually work its way up from a tinkle.” Does this precision occur, or have to occur, in those first paragraphs, is it natural for you to write that way, or do you introduce this finicky aspect into the narrative as you build the character?

SS: No, it is not natural for me to write that way. This was a trait belonging to those characters, not to me, a trait reflective of their personalities, though it functions differently in the two cases. I don’t in fact write like any of my characters.

JB: After those first few paragraphs, if they look to be going well, do you make notes about things you would like the character to say?

SS: Yes. Things like that pop into my head at all hours, and I jot them down and later put them in a folder that I label “material.” Some end up in the novel, a lot more prove useless.

JB: How do you know when a project is or isn’t going well?

SS: I know it isn’t going well when it stops going, when further paragraphs fail to appear. I struggle with it for a while – where “struggle” means staring out the window – and if nothing comes, I drop it. That’s the usual way. Lots of false starts. But now and then the character takes over. It’s a feeling many novelists have, I think – that the character, or the writer’s unconscious mind, takes command of the story to such an extent that you feel you are taking dictation.

JB: I’ve mentioned how a tale about a rat can be affecting. Did you think that as you wrote? I don’t mean that you’re calculating how to wring pathos from vermin. But do you feel the emotional truth of your writing as you go on, line by line? In case anyone thinks that there is only misery and grief in your novels, I should say there are passages and lines that have made me laugh, unexpectedly most times. Do you feel enjoyment when you write?

SS: I frequently laughed out loud while writing The Cry of the Sloth. It’s an odd thing: I have to force myself to begin writing in the morning. I will find all sorts of excuses to put off doing it. When it is going well I can’t say whether I enjoy it or not, I am so completely lost to myself. Nabokov referred to his characters as his slaves. Maybe that is a common sentiment among grand Apollonian novelists. But in my case it is just the reverse of that.

JB: Are you, then, a slave to the characters?

SS: Absolutely.

JB: You say you’re “an old-fashioned realist…” I might differ when you leave it there. But perhaps you might define that term before we go on.

SS: I don’t mean anything technical by it, just that I hope I have created thoroughly believable characters who live in a world we recognize as our common world, however distorted it might appear when seen through the eyes of my narrators, and that includes Firmin. Most of the richest characters in literature belong to the realist tradition. I think it is mainly the subjectivity of my works that distinguishes them from classically realist novels.

JB: Whenever I read your books and the works of some others—Gabriel Josipovici, Cesar Aira, and Karl Ove Knausgaard are examples—I become wrapped up in them, even with pen and notepaper at hand, and my notion of reality gets nudged sideways. The intensity of the way you present manias and severe anxieties, set within a claustrophobic environment of one character’s consciousness and one person’s physical space, displaces my own consciousness temporarily, an aim I assume you have. It therefore robs me of whatever reality I own (however provisionally), a state of affairs that lasts for a bit after I close the book. I feel my presence and the narrator’s presence—or maybe saying the narrative’s presence is more accurate—mingling. Slowly my mind becomes my own again, but it is coloured—it has been coloured since Firmin—with what you have written. Hopefully—hopefully on more than one level—I’m not the only one who responds that way. I close the book and your reality is there, and what was mine is not, not right away, and not in the same way after.

What I want to get at it is that your version of a “common world,” perhaps against what traditional or current realists (Jonathan Franzen, perhaps) say is theirs, replaces what readers experience, if they allow themselves to sink into the writing. We can agree that the characters are subjectively realistic, but how are you only a realist when, first, the thinking and experiences of Firmin, Andrew, and Edna, to use the most extreme cases, are skewed or “distorted,” according to conventional standards, to the extent that they aren’t in what some would consider the real world—by which is meant the sane, commonsense world—and, second, when you posit alternate worlds with such fidelity and relentlessness?

SS: I am happy that in your case the books have had such an effect. And, as I said earlier, that is precisely my intention. But I insist, my characters are in the common world. All I have done, through the skewing and distorting you mention, is simplify that world so everyone can see, to use William Burroughs’ phrase, what is on the end of every fork. I would guess that if the state of affairs presented in the novel temporarily displaces your own consciousness, as you say, that is because you recognize that it is your world too.

JB: I’ll consider that last remark, but away from this interview.

That “sparseness of the verse” of the Objectivists and Black Mountain poets remains with you as you aim to simplify?

SS: I don’t think so, not in the sense they intended. Except for It Will End with Us I don’t think of my novels as sparse. “Concise” is the word I would choose. As I said, I feel closer to Berryman, who is about as far from those guys as you can get.

JB: Where and how do you write? By hand, on a typewriter or computer? And could you describe your process of revision? Is there much editorial discussion with Coffee House Press?

SS: I write on a computer. Before computers, I used a typewriter. On a computer I am able to try out sentences, turn them this way and that, as many times as I like, something one is loath to do on a typewriter or in longhand. I fiddle with them endlessly. When revising I save the work as a new file and rewrite from the beginning. I seldom go back and rewrite individual parts, since by doing that I would lose the feel of their place in the whole, the tempo, for example, or the overarching mood in which they are inserted.

I have rewritten a novel many times before Coffee House ever sees it. They get a clean piece of work. The editors make some suggestions, but they never attempt to override my decisions. All writers should be so fortunate. After reading the manuscript of Glass the late Allan Kornblum, publisher and founder of Coffee House Press, said, in a warning, “It’s hard to recover from a book like this,” meaning I was heading for disastrous sales and a reputation for not selling that would dog all future books. He was right, of course, but he published it anyway.

JB: Do you print parts of or the whole manuscript and edit by hand after writing on the computer?

SS: No. The only novel I printed out before finishing was Glass, and it is also the only novel whose parts were radically rearranged ex post facto. I printed the novel and chopped it into pieces, maybe forty or fifty, and spread them out on the floor of the living room. Then I walked around and rearranged them. It was the only way I could manage an overview of the whole thing.

JB: We’ve talked about the kinds of writing you attempted before finding your true voice. In The Cry of the Sloth Whittaker’s letters make up the bulk of the novel, and we are also presented with his diary entries and fragments of his own fiction. Did you use discarded writings of your own or were these bits created during the process of writing?

SS: They were all invented for the occasion.

JB: How was it to write those parts?

SS: Writing for me is a form of impersonation, I think I can say, and so this novel was the occasion for a much larger variety of “experiences” or, maybe, “performances.” If I had a chance to relive the writing of one of my novels, I would choose it.

JB: You mentioned laughing while writing this book. Was it fun to create such a waspish figure as Whittaker? He has some very good lines.

SS: Yes, it was often fun, but sometimes he would break my heart.

JB: What meaning does Whittaker search for, and do you think it’s fruitless? When I read that book, with its time setting in the Nixon era, it seemed to bring together the mess of his own home and the devaluation of property, as mentioned above, with systemic corruption of an organizing entity. How could Whittaker find positive meaning when surrounded by such competing forces?

SS: Near the end of the novel Whittaker says, “I have unpacked my soul and nothing is in it.” He has arrived at the end of his illusions. The image of himself that had guided and oppressed him has been shattered, and he is free. Free for death, possibly, but also free for another kind of life.

It is at that point, in that spiritual desolation, where the constructed self has come undone, that the next three novels begin.

JB: Are these novels a quartet or quintet, then, if we include Firmin? Or do Glass, The Way of the Dog, and This Will End with Us make up a trilogy? How would you characterize the sequence, and would you have an overall title for the works?

SS: I didn’t intend them that way, but in retrospect I can see that the last three do form a sort of trilogy. I would love to see them in a single volume. Maybe I would steal a title from Raymond Chandler and call it The Long Goodbye.

JB: Edna in Glass has to type. This seems to be what she does most. How did you come up with that?

SS: I’m not sure. She was already typing when I met her. But forty years ago I was friends with a man who lived in a basement and “processed” his life, as he put it, writing down everything he thought or experienced in one notebook after another. Though he worked at it for hours every day, he was falling steadily behind, life was unrolling faster than he could record it, to his great distress. He might have been the inspiration for Edna.

JB: In the novel there appears this passage: “I could not think of anything to type at Potopotawoc. Sometimes I copied things out of magazines, I typed an entire issue of the New Yorker, including the ads.” When critics responded to The Cry of the Sloth by thinking it to be a satire of the literary world, you found that not to your liking. But here is another of your characters who performs, unwittingly, an act of uncreative writing. Are there grounds for reviewers to wonder how far apart from the literary world you are? Or maybe you’re far apart from that world, but not from its interests, movements, and concerns.

SS: I am a writer, and writers of all stripes have concerns and interests in common. So in that sense I am a part of the literary world. I read the New York Times Book Review, I subscribe to Bookforum. It’s just that other writers are not participants in my social life, such as it is.

JB: We can’t trust Edna’s version of events any more than we can Whittaker’s. She has a very jaundiced view of her dead husband, Clarence Morton, a writer. The at times unpleasant Whittaker, though that’s not by any means a rounded view of him, is also a writer. Is it a simple convenience to choose writers as figures of derision or do you think negatively of them as a class or group?

SS: I don’t think negatively of writers generally. I don’t care for the ones who are windbags, pontificators, or arrivistes, but who does?

JB: In Glass Edna repeats a comment Morton made, that she thinks too much. Is that possible?

SS: If happiness is the aim then one surely can think too much. I suspect that’s what Morton was suggesting.

JB: Could Morton have meant something else that Edna skewed to her liking?

SS: Sure. He might have been expressing his frustration with a mind that turns in circles, or, better, in spirals, and with a woman whose “unmarketable” ruminations are a silent reproach to him and his hunger for “success.” But as to what he “really” meant, your guess is as good as mine.

JB: At the end of Glass there appears to be deliverance for Edna from her state, to speak vaguely so as not to ruin the experience for future readers. It’s one of the ambiguous endings frequent in your books. How much time did you spend on those last pages?

SS: A lot. I rewrote those pages dozens of times. There was the absolutely important final phrase, “and then I will see,” and I struggled to build a scaffold to it.

JB: To me, Glass is the most overtly philosophical novel you’ve written, due to Edna’s focus on language and her exactitude of impressions, and the dusty glass in her eyrie-like apartment that gets murkier as her economic state declines, speaking, perhaps, not only to Edna but to humanity’s condition of humanity. Do you view the book as your most philosophical?

SS: I don’t know that it is the most “philosophical.” I would apply that label to The Way of the Dog, with its ruminations on story and meaning. But I suppose the judgement here will depend on what sort of thing one regards as philosophical. That said, I have no objection to your description.

JB: In The Way of the Dog you move from the writing world to the art world, but the picture you provide is no more positive. Did you have bad experiences in the art world?

SS: I have known more painters than writers, but I have no bad experiences to report.

JB: What painters? What were those interactions like? Do you collect art?

SS: My oldest friend in the world is a painter in France. Impossible to describe such a friendship, short of a book. I don’t collect art.

JB: Harold Nivenson, the narrator, is unwell, and is missing Roy, his dog, who as you said is “emblematic of acceptance and wisdom.” I suppose I could start by asking about your experience with dogs.

SS: I grew up with dogs all around and have lived with dogs, often multiple dogs, whenever circumstances permitted. We have a dog now. I am fond of her, I show it, and she responds. Her predecessor, a marvelous fellow, was dying at my feet while I was writing the novel.

JB: Had you started the novel knowing he was dying, or did this start partway through?

SS: I wrote the first two paragraphs thinking of him, of his impending death, of myself without him. At the time I thought I would not live to write another novel. Hence the paragraphs:

I am going to stop now. A few loose threads to cut, some bits and pieces to gather up and label, so people will know, and then I stop.

I had a little dog. We went through the world together for as long as he lasted, through the world this way and that, just to be going. At the end he had grown so weak I had to prod him onward with my shoe. He is buried somewhere. His name was Roy. I miss him.

So the entire novel, in a sense, came from the presence of the dog at my feet at that moment. I should have listed him a co-author. His name was Bertram. I miss him.

JB: Nivenson is often mean, though to balance that he does love Roy, his dog, and is aware of how he behaved when younger. People drift back into his life, like Molly and Alfie, but before that has much effect we are treated to his impressions of his neighbours. For you, this is a large cast. Was there a different kind of thinking present to accommodate the presence of other characters than from your earlier books?

SS: I don’t see a big difference in the kind of thinking. More people make appearances in this novel than in the others, but none except Moll and the painter Meininger rise to the level of being characters.

JB: Unnamed family members and unnamed former wives are mentioned. This may seem an odd question, but what does it take for a character in your books to be bestowed a name? For it often seems like a dispensation.

SS: They get names if I want to be able to refer back to them in a later passage. If there is only one sister, for example, she becomes “my sister.” Her name doesn’t tell us anything, so why say it?

JB: The presence of Buddhist sayings in this novel is not a typical feature of your works. What significance do they have, and were they used only for the book, or do you see something in Buddhism that appeals to you?

SS: At one time I read a lot of Buddhist works. I still do sometimes. My younger son is in his ninth year at a Tibetan institute in India, undergoing the traditional training of a lama. When I am reincarnated I hope I will have the good sense to become a Tibetan monk.

JB: We’ve come to It Will End with Us. Last year for Numéro Cinq I reviewed it, and I’d like to come back to something you said a while ago about your mother, as it relates to Eve Taggart, the narrator of this latest book. Her mother, Iris, is an unpublished poet who’s slowly losing her mind. Eve says this about her writing: “I was fifteen when I finally understood that my mother’s poems were not literature.” In your interview for Poets & Writers from fall 2011 you talked about your mother’s ability to recite poetry from memory, and how much she admired Keats. Did you find her abilities—and I think how you learnt to read, and your sister’s memorization of the dictionary—normal and worth emulating?

SS: Of course. She was a fabulous reader, a great “admirer” in the sense I explained earlier. My family was unusual in many respects, and for me unusual was normal. I can’t begin to even approach my mother’s knowledge of literature nor, I think, do I have the capacity to draw from it the comfort that she did.

JB: What do you draw from it?

SS: Pleasure, of course, at times exquisite; distraction from daily care; insight into what Yeats called the foul rag and bone shop of the heart

JB: In that same interview, you also say your mother “‘…had less of a life than she should have had.’” Readers of It Will End with Us will think of Iris and compare that portrait to what your mother was like. Elizabeth Jones Savage wrote poetry that was published, but I gather that was not enough. Could you say a bit more about her life, and how much she was a model for Iris?

SS: She was not a model for Iris, except very tangentially. My mother would probably have been happier in a Northern city than in a small Southern town, but she was not a tormented woman like Iris. She was extremely kind and gentle. She was soft-spoken and witty. She was, I think, a very wise person. She would have been happier elsewhere, but she had a rich life, and it was a happy life on the whole.

JB: In It Will End with Us Eve is conscious of the absence of animals in her new home, especially birds, and at one point she lists species she used to see in Spring Hope, where she was born. Her family has no descendants, the South is shown in decline, and in the largest sense, the world is fading away as animals slowly disappear from sight. Eve and Spring Hope could be Eve and Eden. Since your latest novel potentially includes everyone in its title, and addresses global concerns, are we meant to see it as an epitaph, an appeal, a warning? With humanity on the brink, is the first woman seeing herself as the last woman?

SS: As regards the natural world, the title can be seen as all three, I suppose, but the mood of the novel is mostly one of mourning, so I think “epitaph” would be best. It is important to note that the “declines” you mention are not at all parallel. In the case of the South the decline is of the old South, the premodern South, a conservative and deeply unjust region that during my childhood was rapidly vanishing beneath the homogenizing imperialism of American cultural sameness, and becoming what the “Old South” is today—a vulgar and ugly parody of itself, the historical wing of Disney World. My childhood is deeply attached to the old dying South (with no caps or quotes), and I can still summon the love I felt for it, but I can’t in good conscience mourn its passing.

JB: Do you have a dim view of our collective future? This isn’t that dystopian novel you tried to write in the science fiction genre, but is it aiming towards that?

SS: I have a bleak view of our collective future. That humankind will survive in the long run does not look like a safe bet at this point. I am not even sure that human survival is something we should wish for. I have no difficulty imagining a not-so-distant future so awful it would be better to have no future at all.

JB: Is there a connection between the use of Biblical imagery here and Buddhism in The Way of the Dog? I mean in your technical use of both and in drawing useful imagery from these sources for the narrators to comment on or, in Eve’s case, perhaps embody.

SS: The imagery was appealing, given the circumstances, but the two cases are quite different. In one it sets up a theme of compassion and acceptance against Nivenson’s bitterness and anger. In the other it evokes a lost paradigm of innocence and perfection in the life of the planet to parallel Eve’s recollection of her banishment from the small Eden of her childhood.

JB: You have a story in the latest Paris Review (No. 211, Winter 2014), “Cigarettes,” one paragraph over two pages of a man and his landlady talking about smoking. She says she should quit but can’t, and often borrows a cigarette from the unnamed male narrator. One thing she says is: “‘Next time I decide to stop, you need to tell me it’s not worth it.’” On the surface it’s an amusing sentence, in context, but here’s a woman looking to have her aim deflected even though she knows smoking is unhealthy. What makes your characters undercut their own motivations?

SS: Well, it seems to me that there is often, and maybe even always, a difference between what we tell ourselves we want or even sincerely believe we want, and what we really do want. The human project, so to call it, often involves finding the right lies to tell ourselves so we can get though the day, and the right tune to whistle as we walk past the graveyard. We are, needless to say, frequently unsuccessful in this project, often because we have other yearnings that undermine it. This is basic Dostoyevsky, by the way, and basic Freud: living characters are never mere collections of traits—they are collections of elements at war with one another.

JB: Is this story part of a collection or an excerpt from a novel?

SS: While I am waiting for a novel, I write little things. They are, I suppose, the debris left behind by my searches for a novel, outgrowths and trimmings of aborted starts. Some are ten or fifteen pages, many are not more than three or four sentences. Some of the shorter ones were published a few years ago in the journal Little Star.

JB: Are there plans for a collection of those pieces? I’d like to see them in book form.

SS: I play with the idea sometimes, of ways I might arrange them so as not to present just a grab bag of disparate stuff. I have a lot of trouble estimating the value of many of them.

JB: Who are you writing for? Do you have an ideal reader?

SS: The ideal reader, I suppose, would be myself as other. By that I don’t mean that I write for myself, far from it, but that I think of my reader as being someone with tastes and inclination more or less in line with my own. That is not, given my personality, a great formula for success in the market.

Sam Savage 2007

Sam Savage 2007

Conclusion

JB: Do critical reviews of your work mean much?

SS: By “critical” I suppose you mean negative and not the sort of literary-critical review that you, for example, have written. The answer, in that case, is that I have never received a negative review that I felt touched by. I have never in fact received a negative review at all, if by “review” we mean more than a half-dozen sentences and the granting of little stars, just like in first grade. That, I think, is because a reviewer doesn’t earn any stars for him- or herself by negatively reviewing a book which people weren’t going to read anyway. You get creds in the review world by climbing in the ring with somebody other than some weird old guy who just wandered in off the street.

JB: Is there any question you’ve wanted to be asked but have not been? If so, here is an opportunity to answer it.

SS: Maybe something like the question that Nora Joyce is rumored to have asked Jim: Why don’t you write something that makes sense so we can get a refrigerator?

His answer was not recorded. Nor will mine be.

JB: Before we end, I’d like to return to the subject of your unpublished fiction and poetry, as well as your letters, and any other material a writer might leave behind for institutions and biographers. I’m rather regretful, if you don’t mind me saying, to hear you tossed away so much, and I wonder why that’s your practice. Biographers will be frustrated.

SS: I am a very private person (weird in this day and age, I know). I don’t like the idea of strangers rummaging without restriction in my life, in my past, or in work that I thought not good enough to publish.

—Sam Savage & Jeff Bursey

NC

Jeff Bursey is a Canadian literary critic, and author of the forthcoming picaresque novel Mirrors on which dust has fallen (Verbivoracious Press), and the political satire Verbatim: A Novel (2010), both of which take place in the same fictional Canadian province. His academic criticism has appeared most recently in Henry Miller: New Perspectives (Bloomsbury, 2015), a collection of essays on Miller and his works by various writers. Bursey is a Contributing Editor at The Winnipeg Review and an Associate Editor at Lee Thompson’s Galleon. His reviews have appeared in, among others, American Book Review, Books in Canada, The Quarterly Conversation, Music & Literature, Rain Taxi, The Winnipeg Review and Review of Contemporary Fiction. He makes his home on Prince Edward Island in Canada’s Far East.