Christopher Ryan, Ph.D. & Cacilda Jethá, M.D.

Christopher Ryan, Ph.D. & Cacilda Jethá, M.D.

/

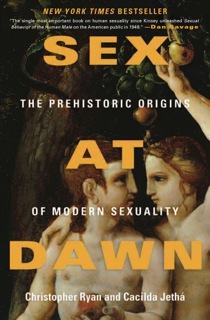

Sex at Dawn: the Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality

Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jethá

Harper, 416 pp., $25.99

ISBN 9780061707803

John Gardner’s lovely On Becoming a Novelist claims that readers have two big incentives to get through long blocks of prose: story and/or argument. In Sex at Dawn: the Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality, Christopher Ryan (PhD) and Cacilda Jethá (MD) offer a little of the former and plenty of the latter. With kilos of scientific homework, not home-wrecking confessions, they tell the polyamorous story of human evolution as an argument for contemporary tolerance for open relationships and other strategies for more sexual-social-spiritual contentment and less work for divorce lawyers.

Those of us who teach know that few lessons are as powerful as Thomas Kuhn’s revelatory paradigm shift. Ryan and Jethá start their polyamorous argument in a double bind: Western culture has been so thoroughly and punitively mired in the monogamy paradigm that even the scientists (from Darwin to Stephen Jay Gould) who should be helping create an accurate reflection of open human sexuality often misinterpret, misrepresent or misguide us with physiological and historical evidence that should be a clear argument for some divisions of sex, love and family. To their credit, Ryan and Jethá (a couple) turn this challenge into a key opportunity for this measured, informed account of human sexual mutability. This wake of human intellectual development and the social management of knowledge (plus 65 pages of notes and references) make Sex at Dawn much more than a martini-soaked argument for a key party.

The antagonists of the Sex at Dawn story are (recent, proprietary) monogamy, close-mindedness and unwise policy. Its various protagonists are human and (other) primate anatomy, evolutionary survival, wide-eyed history, and brave honesty. In emphasizing that humans, our closest primate relatives, and proto-humans are physiologically hard-wired for polyamory, Ryan and Jethá make a historical and biological argument, not a revolutionary one. With fact after fact they demonstrate that we almost always have been polyamorous and are physically if not evolutionarily equipped to be so. Citing past precedent and current failure, their argument is much more palpable and significant than any proselytizing campaign. Sex at Dawn doesn’t argue that we should convert to polyamory; it argues that we almost always have been polyamorous and should be again given our current failure at monogamy. Their citation of Schopenhauer’s 1851 essay “On Women” gains additional relevance as we consider contemporary divorce rates, what American literature profs Carmine Sarracino and Kevin M. Scott call The Porning of America, and the global sex trade: “In London alone there are 80000 prostitutes [in 1851!]. Then what are these women who have come too quickly to this most terrible end but human sacrifices on the altar of monogamy?”

Ryan and Jethá’s attention to human sexual anatomy is crucial to their argument that if we want healthier bodies, relationships, and societies we should revert to polyamory. Their comparisons to other primate genitalia and sexual behaviour foreground that theirs is an argument from science, nothing faddish like ‘alternative lifestyles.’ A handy diagram summarizes their repeat and varied attention to the large penis and testicle size of polyamorous humans, bonobos, and chimps (where males aren’t too much bigger than females) compared to polygynous gorillas, where males tower over females to fight off other males then impregnate multiple females with their (relatively) miniscule penis and testicles [truck size joke anyone?]. Gibbons are monogamous and equally sized between the sexes, but they also don’t shag very often and don’t, unlike randy humans and bonobos, ever copulate facing each other. The testicle size issue is illuminating. Male gorillas fight to be the one inseminator of multiple females, so they have put their evolutionary work into arm and chest strength and have “kidney-bean sized” testicles buried up in their bodies. The primate playahs (humans, chimps and bonobos) have evolved sizeable testicles to frequently produce large volumes of ejaculate so their sperm, not their arms, compete within females who have multiple partners.

Ryan and Jethá’s attention to male and female anatomy is illuminating [oh the back-pumping male penis; oh the attacking acids in the first spurt of male ejaculate], and they augment it with genuine curiosity and intellectual history. In a truly remarkable connection they observe the intellectual taint of biases and reception chronology shared between our current (misinformed) monogamy paradigm and the massive research preference for chimps over bonobos. Genetically, humans are equally similar to combative (and horny) chimps and cooperative (and really horny) bonobos. However, chimps were discovered and brought into comparative research earlier, and various lasting comparisons were cast. Their quotation of Frans de Waal’s Our Inner Ape is a cri de coeur for the social improvement, not just sexual adaptation, Ryan and Jethá advocate:

I sometimes try to imagine what would have happened if we’d known the bonobo first and chimpanzee only later or not at all. The discussion about human evolution might not revolve as much around violence, warfare, and male dominance, but rather around sexuality, empathy, caring, and cooperation. What a different intellectual landscape we would occupy!

As a (rational and compassionate) argument, Sex at Dawn draws as much evidence from history and anthropology as it does from anatomy. In a forthcoming book of poems about evolution, I use a corporeal dramatization of planetary evolution to illustrate the same evolutionary timeline so central to the Sex at Dawn argument. Stretch your arms wide and imagine the creation of Earth at your right fingertips. For the vast majority of planetary history, past your left shoulder, only bacteria existed. Sex didn’t evolve until past your left elbow, as complex plants began to reproduce sexually. Dinosaurs roamed around in the palm of your hand and humans arrived in just the end of your fingernail. Ryan and Jethá treat that fingernail paring forensically and anthropologically, stressing that the vast majority of proto-human and human evolution was spent pre-agriculturally in hunter-gatherer tribes. Nomads who needed to band together to survive were evolutionarily rewarded for cooperation and sharing. The vast majority of human history was spent sharing food, genes and child-rearing. Ryan and Jethá compare early humans and twentieth-century hunter-gatherer tribes in which rotating sexual partners meant any man could be the father of various children and therefore all men provided for all children. Later they contrast that cooperative child rearing with the high divorce rates and the very large fraction of single-parent families in contemporary America, citing studies which show that single-parent children under-perform on “every single significant outcome related to short-term well-being and long-term success.” As Ryan points out in one of his two stimulating appearances on Dan Savage’s sex-advice podcast, only with the very recent human switch to agriculture did humans shun cooperative, communal ownership (and polyamory) for private ownership of land, seeds and their heirs (through monogamous marriage).

How Reymont and Melusina were betrothed / And by the bishop were blessed in their bed on their wedlock. From the Melusine, 15th century.

While the thoroughness, variety and balance of Ryan and Jethá’s case are crucial to demonstrating what to many will still be a radical thesis, the abundance of evidence actually becomes a rhetorical challenge. Admittedly, logic and organizational ease do favour a loosely chronological development from proto-humans to (racier) later chapters on the West’s policing of the female orgasm. In general, the first half is more anthropological and the second, much more gripping half, is anatomical. Readers interested in—forgive me—hard persuasion may appreciate anthropological example after example, but there’s a risk of losing sight of the argumentative forest for its evidentiary trees. References to South American tribes, remote Chinese communities and enlightened Indian provinces are important reminders that divisions between sex and love are healthy and that human behaviour, not just anatomy and bonobos, favour multiple sexual partners. Nonetheless, chapter after chapter of anthropology may prevent readers from getting to the later, better chapters. Without Sex at Dawn, who would know that “By 1917, there were more vibrators than toasters in American homes”? The argumentative foreplay is great. For a while.

—Darryl Whetter

/

Darryl Whetter’s latest book is The Push & the Pull, a novel of bicycling and bisexuality. In April 2012, he will release a debut book of poems about evolution (including the evolution of sex). He’s also at work on a novel about polyamory.

/