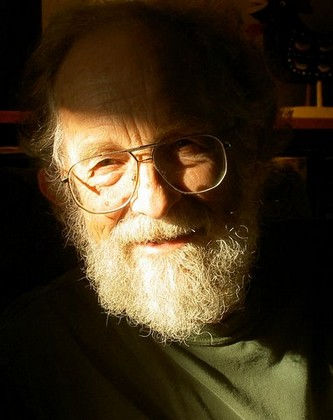

Mark Anthony Jarman is an old friend dating back to our days at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He’s from Alberta, lives next to the Saint John River in Fredericton, New Brunswick, where he teaches at the university. He plays hockey, wrote a hockey novel, has three sons, and was a regular pick when I edited Best Canadian Stories. He is the subject of my essay “How to Read a Mark Jarman Story” which originally appeared in The New Quarterly and can be found in my essay collection Attack of the Copula Spiders. He writes the wildest, most pyrotechnic stories of anyone I know.

This story originally appeared in Darwin’s Bastards: Astounding Tales from Tomorrow, edited by Zsuzsi Gartner (Douglas & MacIntyre, 2010).

dg

/

The distance I felt came not from country or people; it came from within me.

I am as distant from myself as a hawk from the moon.

James Welch, Winter in the Blood

I was lost in the stars, but not lost, my tiny craft one of many on a loop proscribed by others, two astronauts far out in a silk road universe of burning gas and red streaks, and one of us dead.

Then the land comes up at us, the speed of the land rushing up like film and our Flight Centre men at serious blinking screens. Our valves open or don’t open, the hull holds, the centre holds, little I can do. The dead man is not worried. I will not worry anymore, I renounce worry (yeah, that will last about three seconds). The angle of re-entry looks weird to my eye. I had to haul his corpse back inside for re-entry so he wouldn’t burn up.

In the city below me traffic is backing up into the arterial avenues. They want to see us return, to fly down like a hawk with the talons out.

“Units require assistance. All units.”

We are three orbits late because of the clouds and high wind. They want to be there if there is a memorable crash, our pretty shell splitting on the tarmac into several chemical flash-fires engraved on their home movies.

We were so far up there above the moon’s roads, my capsule’s burnt skin held in rivers and jetstreams that route our long-awaited re-entry. Up there we drive green channels riven in the clouds, ride stormscud and kerosene colours in the sky, then we ease our wavering selves down, down to this outer borough, down to rumpled family rooms and black yawning garages, down to the spanking new suburb unboxed in the onion fields.

I’m a traveler, an addict. I descend from the clouds to look for work, I was up there with the long distance snowstorms. It’s hard to believe I’m here again, hard to believe Ava became so uncaring while I was gone from the colony.

Ava’s messages are still there. “This message will be deleted in 2 days.” I press 9 to save it yet again. I save her messages every ten days, my private archives, my time capsule, a minute of her lovely voice.

“Loved your last transmission,” Ava said in September. “It made me laugh! And I loved the pictures you sent! I can’t wait to see you.”

But then the change in October, the October revolution. We are changelings locked in a kingdom of aftershave ads and good shepherds, lambs and lions and the Longhorn Steakpit’s idea of a salad bar.

Her messages were so very affectionate, and we’d lasted so long, so long, but in the end our messages were not enough. Our words were not enough. A week of silence and then a new message. I knew it.

“Some bad news,” as Ava termed it. She’d met someone else, she’d had a lot to drink, one thing led to another. And I was so close. Only a few days more. But she couldn’t wait for me. So long.

In the Coconut Grove bar in the afternoon I’m feeling all right. I’m good at clarity and appreciation, but I’m slightly out of time. Time slows and I lurk in it, I can alter it. Do you know that feeling? I drink and carefully move my head to study my world. Venetian blinds layering tiny tendrils of soft light on us, the purple tennis court on TV, an AC running low, the lack of real sky. It all seems okay, it all seems significant, it all seems deliberate and poised for some event. But only to me, only I know this mood, this valiant expectation, this expedition into the early realms of alcohol.

Perhaps I am not quite right, but I savour the strange interlude. I’m a lonely satellite in space, a craft drifting alone, drinking alone. In this room the music is fine, the hops have bite – the perfect bar moment.

Then the bartender cranks up the volume on Sports TV and snaps to his phone, “The girl who cut my hair butchered it. I didn’t have the heart to tell her, you suck.”

And that’s the end of my spell, the end of that little mission to Mars. And I was so enjoying it.

“Hey dog, you flew with that dead guy, didn’t you? And then your girl dumped you. She’s hot. Bummer, man.” I wait until the bartender goes to the washroom to work on his hair and I exit without paying.

Maybe not the smartest idea, but I call Ava in Spain. She left me, but she’s the only one who will know what I mean.

“What do you want from me? Why are you talking like this?” Her slight laugh.

Apparently I have some anger to work out.

Turquoise mountains at the end of the street remind me of Tucson or Utah. The mountains of the moon. I kill time walking. Funny to be on foot once more. The sun and earth – what are they to me? I still orbit Ava, but she’s not there, no there there, so to what furious solar system do I now pledge my allegiance? I still orbit her blue-eyed summer kitchen memories and the cordwood and pulpwood childhood in the north.

Need to change that orbit, need orbit decay.

In the building where she used to live they now deal ounces and eight-balls. I was gone, Ava’s gone, the moon has changed.

Not sure I like the messages I’m picking up re the new frontier. No one foresaw this, crystal and crank smuggled in to the colony, dealers and Albanian stick up crews and crummy walk ups, the adamantine miners working the face under Dwarf Fortress, all the single males earning big bucks in the catacombs and mineral mines, but with nowhere to go, the shortage of places to live, the exorbitant cost of milk, the new gang unit brought in, dead bodies on the corner with splayed hands and wrists smeared red with their own blood, and bouncers at the door working hard at that Russian look. With the economy in the toilet the Minister of Finance is studying the feasibility of holding Christmas four times a year instead of two.

At the reception for me and some other space cowboys the party crackers lie like ashes on my tongue. The fruit salad fallen from soldered tins; taste the fruits of duty. My long periods of radio silence and now the noise of crowds and halls of ice cubes.

My brother-in-law Horse the detective is at the reception with a woman he says has just moved to the moon from Babylon to escape the war. Delia looks nervous, as if still in a war zone. Her family made her leave her home, smuggled her over the border, they feared for her life if she stayed.

Forget this place, they said of the only home she’s known, it doesn’t exist anymore.

“How do you like it here so far?”

Delia says, “People are very kind to me, but it’s not what I thought.” She shrugs. “All my life I wanted to see the moon, stared up at it. But I miss my home, my family, my car, my brothers, the path to the river.”

“Can they visit?”

“No, it’s impossible now.” The family had money, but now it is all gone, they are bankrupted by the war, the stolen gold, the extortion, the journey to other lands. Her English is very good.

“How is the new job?”

“Horse can tell you better than I.”

“Brutal,” says Horse, “A ton of movement with the gangs, a lot of old grudges, eye for an eye. We just had a 27 before we came here.”

“27?”

“It means he was already dead before we got there,” Delia tells me. “Another young guy,” she says. “They get younger and younger. Children.”

Five phones ringing on the silent body, once so talkative, now so grave. How may I direct your call? How come it’s so easy to become a body? He is past saving, his messages will be deleted in ten days unless someone who loves him presses save.

The woman from Babylon asks about my last trip in the light years, where I slept in far stars like fields sown with salt.

“Is it boring out there? Is it better than here?”

“It was wild, hard to describe, almost religious.”

“What about when Curtis died?”

“I don’t know, he was just dead.”

Was it an accident or did he do it to himself? This question is not in the press. One time, after he was dead, I swore I heard a fly buzzing inside the windshield, that manic little taptaptap. I turned my head slowly; there was no fly. I had wires to my skin, an extended excellent dream.

I hear Delia speaking Arabic on her phone. Her uncle is a consul in Vietnam with an Irish wife. We, all of us, have come so far from home.

Very few of the December class returned alive. There is a chance they are still out there, or else something is killing them, making them martyrs. Or perhaps some Decembrists stumbled onto a beautiful world, and chose to not steer back to this one. Why am I the only one who found a course home? And to what?

It’s just survivor’s guilt, the detectives insist. Take up golf. Some good 18 hole courses on the moon, especially the Sea of Mares, Sea of Tranquility, condos with fake pools stocked with trout fingerlings.

“You can rent an AK at the range,” says Horse. “Or sled down Piston Alley.”

Piston Alley is named for all the sled engines that have blown pistons on the long straight stretch. The engine runs the best ever just before the piston shoots out like a tiny rocket. I don’t really want an AK47.

In the NASA gymnasium the trainee astronauts play tag. Astronauts get lots of tang; that was the old joke. Poontang. When I was out there I craved smoked salmon and dark beer. The dead man went on for hours about steak and ice cream. I have a few too many bank loans. Curtis was outside when it happened, his air.

The woman from Babylon stares at me with her very dark eyes, says, “I wonder if perhaps you would help us in the interview room.”

Did Horse put her up to this?

He says, “The Decembrists are famous with the school-kids.”

“But with these jokers you pick up?”

Horse says, “You’ve always been better than me at reading faces. You can let us know when it’s a crock. We’ll have signals.”

Horse makes it seem like a job selling vacuum cleaners.

“Think about it. Something to do.”

Something to do — he has a point. Maybe a distraction from Ava in my head. I have escaped gravity and achieved a kind of gravitas. Yet I feel a broken shoe. I can’t sleep (night and day), my mind locked on her with someone else (day and night I think of you), and the lymph nodes each side of my groin are swollen tight as stones inside a cherry; no idea what that’s about, what’s next, what’s approaching me.

They are ploughing a new road by the graveyard, by the old settlers and the new settlers in the cemetery under Meth Mountain. The lumpy graves look to be making their slow way across the whitemoon’s dusty field, the dead in their progress to us, their magnetic message under clay walls and organic reefs and the moon’s Asiatic peaks just past the plywood windows of the closed mall.

Ava quit her job and got away, but when I filled out a Planet Change Request Form it was turned down by upstairs. I know it’s not a planet, but that’s the form they use. At the drive-through window on Von Braun Boulevard I order a combo and a willowy uniformed teen hands me a paper bag.

“Enjoy your meal.”

I drive to the carved-up picnic tables by Lost Lake. Opening the bag, I find $6000. They have handed me the day’s receipts. Or gave something to the wrong car. Someone will be pissed off. And where are my fries? I’m not driving all the way back down the mountain.

Now, how to use $6000? Pay down the loans or just buy a giant TV? I’ve always wanted a jukebox or to buy a bar in Nebraska. Maybe I will. I can learn things. Ava said, Whosoever wants to be first must first be slave to all. That night I sleep among the fences under stars where I rode so long. Perfect carpentry is a thing of amazing beauty.

Downtown I see Delia walking by the Oppenheimer Fountain. She seems shy. I feel her lovely eyes hide something, some secret limit inside her. Is she resigned to it? I like the idea of a secret, like her face.

“So I can just ride along in the car?”

“Hell yeah you can ride,” says Horse. “That’s it exactly. A goddam team!”

I can ride, privy to the children selling ghost pills stepped on a few times, dividing the corners, eyes like radiogenic freeway lights. It’s the Zombies versus the 68th Street runners, yellow flashes on a dark wall and the Indian Head Test Pattern, and from this world of instant grudges we pluck the sad eyed murderers and take them into Interview Room #2, where we strive to arrive at some form of truth acceptable to most of us.

Everyone loves truth. Ava told me the truth, did she not? She loves me, she loves me not. It’s a gamble, shooting dice while clouds boil around the sun, goading the dominos.

Who controls the corner, the zoo? We travel to the far corners of the universe, but we can’t control the local corner, can’t control the inside of our head.

In the interview rooms prisoners must be checked every 15 minutes. Someone slumped there in a chair killed a son, a cousin, killed in the triple last time. Horse walks in with his coffee. It goes on, it goes on.

They seen you riding with Moonman and Mississippi and Ghost.

Seen me?

You been slinging dope?

I don’t know no Mississippi.

Tight bags of meth hidden in the torn baby-seat.

Where were you rolling?

Nowhere. You know, just rolling nowhere.

By the fountain her gasmask matches her dress. Males never quite exist for me — only women. I don’t carry a mask; the air inside is fine, but she is very cautious and keeps it with her briefcase.

Five p.m. and the moon goes violet. Free Fanta for all teens at the moon-base chapel. She doesn’t drink and I am a spastic snake.

At dinner she doesn’t know she saves my life just by being there in front of me. I’d rather she not know my sad history, my recent heartbreak. It’s so pleasant to meet someone so soon after Ava, but still, the joy is tempered a tad by the prospect of it happening again, of another quick crowbar to the head. But I resolve to be fun. After the attack on the Fortran Embassy I resolve to be more fun.

Delia says she swam a lot in Babylon before the war, and she has that swimmer’s body, the wide shoulders. She says, “I am used to pools for women only, not mixed. I don’t want to swim in the moon-base pool.”

“Why not?”

“You’ll laugh.”

She doesn’t want to swim with strange men, but also fears catching some disease.

“I was hesitant to tell you about the pool. I feared you’d laugh at me.”

“No, I understand perfectly.”

But now I want to see her in a pool, her wide shoulders parting the water, her in white foam, our white forms in manic buzzing bubbles, her shoulders and the curve of her back where I am allowed to massage her at night when her head aches.

Strange, Ava also had migraines, but I was rarely witness to them; she stayed alone with them in the whimpering dark and I would see her afterward. Beside me in her room, Delia makes a sound, almost vomits over the edge of her bed, almost vomits several times from the pain, her hand to her lips, her hands to her face.

Delia is very religious, very old-fashioned, jumps away in utter panic if I say one word that is vaguely sexual, yet she delights in fashion mags and revealing bras and cleavage in silk and she allows my hands to massage her everywhere when she aches, allows my hands to roam.

“How do you know where the pain is,” she asks me, her face in pillows.

I don’t know. I just know how to find pain.

At Delia’s kitchen table we study maps in a huge atlas, Babylon, Mesopotamia, Assur, where she says her ancestors were royalty in a small northern kingdom. I love the small kingdom we create with each other in our intimate rooms or just walking, charged moments that feel so valuable, yet are impossible to explain to someone else. I saw her in the store, saw her several times in the middle aisles, knew I had to say something.

“I noticed you immediately, thought you were some dark beauty from Calcutta or Bhutan.”

“You saw me several times? I didn’t notice you.”

“But you smiled at me each time.”

“Everyone smiles at me,” she says brightly. “And you whites all look the same,” she adds, and I realize she is not joking.

Her white apartment looks the same as the other white apartments, windows set into one wall only, a door on another wall. I realize both women have apartments built halfway into the ground, a basement on a hill. Yet they are so different. Ava’s slim Nordic face pale as a pearl and her eyes large and light, sad and hopeful — and Delia’s dark flashing eyes and flying henna hair and pessimism and anger and haughtiness. Ava was taller than me, tall as a model. Delia is shorter; I find this comforting.

I close my eyes expecting to see Ava’s white face, but instead I’m flying again, see the silver freighter’s riveted wall, the first crash, then sideswiped by a Red Planet gypsy hack, a kind of seasickness as the Russian team ran out of racetrack, Russians still alive, but drifting far from the circular station lit up like a chandelier, their saucerful of secrets, drifting away from their cigarettes and bottles, from a woman’s glowing face. So long! Poka! Do svidaniia!

The young woman in Interview Room #2 speaks flatly.

They killed my brother, they will kill me if they want.

We can help you.

She laughs at Horse. You can’t help me.

Who to believe? I want to believe her. She got into a bad crowd, cooking with rubber gloves, the game. Our worries about cholesterol seem distant and quaint. She’s not telling us everything, but we can’t hold her.

“I’ve come into some money if you need a loan. It’s not much.”

Delia raises her dark eyebrows in the Interview Room, as if I am trying to buy her with my paper bag of cash. Maybe I am trying to buy her.

“And how am I supposed to pay you back? I have no prospects.”

On her TV the handsome actor standing in for the President tells us we must increase the divorce rate to stimulate the economy. We need more households, more chickens in the pots. I am sorry, he says, I have only one wife to give for my country. We switch to watch Lost in Space re-runs.

At night I ask my newest woman, my proud Cleopatra, “Is there a finite amount of love in the universe? Or does it expand?”

“What?”

“Well, I didn’t know you and no love existed, but now I love you, so there is that much more.”

“Say that again,” she asks, looking me in the eye.

I repeat my idea.

“I think you are crazy,” she says. “Not crazy crazy, but crazy.”

I am full of love, I think, an overflowing well. Perhaps I supply the universe with my well, perhaps I am important. Her full hips, the universe expanding, doomed and lovely, my mouth moving everywhere on her form. The bed is sky-blue and wheat gold.

“How many hands do you have,” she asks with a laugh in the morning, trying to escape the bed, escape my hands: “You’re like a lion!”

She is trying to get up for work. My first time staying over. I am out of my head, kiss me darling in bed. Once more I can live for the moment. But that will change in a moment.

My ex on earth watches our red moon sink past her city. The huge glass mall and my ex on an escalator crawl in silver teeth, at times the gears of the earth visible. We are all connected and yet are unaware. Does Ava ever think of me when she sees us set sail? We hang on the red moon, but Ava can’t see us riding past.

“How many girlfriends do you have?” Delia asks, tickling me. “Many?”

“Just you. Only you.”

“I don’t believe you. I know you flyboys.” She laughs a little at me.

“How about you?” I ask. A mistake.

She turns serious, conjures a ghost I can never hope to compete with. “My fiance was killed,” she says quietly. “He was kidnapped at a protest and they found him in the desert. His hands were tied with plastic. My fiance was saving to buy me a house. My parents told him that I wished to go to school before we married and he didn’t mind. My parents sold their property for the ransom, but the men killed him regardless.”

I remember my parents’ treed backyard; I tilted the sodden bags of autumn leaves on end and a dark rich tea came pouring out onto the brick patio. Do the dead watch us? There were bobcat tracks: it hid under the porch.

Horse says, You know why we’re here?

I watch the boy’s face; he is wondering how much to admit.

Got an idea, he says.

The rash of robberies and bodies dumped in craters and the conduit to the Interview Room and my irradiated bones that have flown through space and now confined in this tiny Interview Room.

You never sell rock?

Like I told you, never.

He’s got a history.

Somebody’s took the wallet before they killed him.

Holy God. Holy God. Dead?

The man is dead. We need the triggerman.

This the t’ing. I have no friends. I learned that.

The young man wants to pass on his impressive lesson to the interrogators, but he has misjudged, his tone is all wrong. He thinks he is good, world-weary, but he hasn’t seen himself on camera, has no distance. The face and the mind, O the countless cells we represent and shed, the horseshit we try to sling.

Man, they had the guns! I was concerned with this dude shooting me in the backseat.

Down the road, what will haunt the victorious young tribes? They’ve heard of it all, but still, nothing prepares you.

You have your ways, Delia says, you can control me.

I wish. I can manipulate her, get some of her clothes off, but I need her more than she needs me.

She says, I don’t think I can control you.

I can’t tell if she thinks this is good or not. We spend time together, but I have trouble reading her, can’t tell if she likes me.

Delia is not adjusting well to being here. She hates the lunar landscape, the pale dust and dark craters past the moon’s strange-ended avenues. She is weary of the crime, the black sky.

“The weather,” she says, “never a breeze, never normal, either one extreme or another. Killer heat, fourteen days! Boil to death! Or else so cold. Fourteen days, freeze to death! Cold then hot, hotthen cold. And there are no seasons. At home summer is summer and winter is winter. Food here has no taste, has no smell. I hate everything and then I hate myself. All my life I wanted to meet the man in the moon and now I’m here.”

“You met me.”

“Yes, that’s true.”

I wish she spoke with a bit more enthusiasm on that topic.

She is losing weight since moving to the moon.

This is not acceptable, she says to the waiter. You would not serve me food like this on earth.

But we’re not on earth. Forget earth.

I’ll make you some of my own, she says to me later. Which she does, a creamy and delicious mélange at her tiny table in the apartment.

Sunday I bring my bag of illicit cash and we shop for fresh spices. We hold hands, touching and laughing in the store, fondling eggplants that gleam like dark ceramic lamps. We are the happy couple you hate, tethered to each other like astronauts. I am content in a store with her, this is all it takes, this is all we want now, red ruby grapefruit and her hard bricks of Arabic coffee wrapped in gold.

Romance and memories and heartbreak: One war blots out an earlier war, one woman blots out the previous woman’s lost sad image, one hotel room destroys the other, one new ardent airport destroys the one where I used to fly to visit her. The only way I can get over her. We are prisoners, me, her, bound to each other like a city to a sea, like a kidnapper to a hostage.

Why did Ava leave me when we got along so well? It was so good. I think I lost something human in the blue glow of that last long flight. Will it keep happening to me? Now I am afraid. The Russians from Baikonur Cosmodrome never returned, the sky closed over them like a silver curtain, like the wall of a freighter.

They went away and I was inside my damaged capsule, inside my head too much, teeth grinding in ecstasy, quite mad. They had me on a loop, my destiny not up to me. We are abandoned and rescued, over and over. But who are our stewards?

We went backwards to the stars. For months rumours have suggested NASA is near bankruptcy, bean counters are reorganizing; my pension is in doubt, as is the hardship pay I earned by being out there. Now we are back to this surface, back to the long runway and smell of burnt brake pads by the marshes and Bikini Atoll.

Me alone in the photograph, the other travelers erased. Or are they out there still, knowing not to come back? You can’t go back to the farm once you’ve seen the bright lights, seen inside yourself.

One day I delete Ava’s sad lovely messages. Why keep such mementos? You burn this life like an oil lamp. You make new mementos, wish they could compare.

I remember parking the car by the dam with Ava. The car was so small we had to keep the doors open as I lay on top of her, but the dome light had no switch. To keep us in darkness I tried to hold one finger on the button in the door and my other hand on Ava. That ridiculous night still makes me laugh, but I need to forget it all, to delete every message and moment.

You are unlucky in love, Delia says. The God is fair and distributes his gifts and clearly you have many talents, but not luck in love.

Is she right? I had thought the opposite, that I had inexplicably good luck that way, but now I wonder; she does seem to know me better than I do myself. I was lucky to know Ava, but now my thoughts are distilled: Ava was too tall, too pretty, too kind.

What I thought was good fortune was bad fortune. Was I bad luck for the Russians? Did I kill Curtis? Strangely, I feel lucky to have met her, to have crossed paths in the long florescent aisles of the store. With my cash from the drive-thru I buy her shoes, an ornate belt, French dresses. She is very choosy, but I like to buy her things.

In her room when I squeeze her hard she calls me a lion. Says I will devour her. I want to devour her, her ample flesh. My tiger, I call her. My tiger from the Tigris will turn. Friday night and we don’t talk, no plans do we make. I thought that was kind of mandatory. Are we a couple or not (Is you is or is you ain’t my baby)? It is odd to not know.

Desire has caused me so much trouble in my life, but I miss it when it is not around. Living without desire – what is the point of life without desire?

Perhaps that is a question an addict would ask.

Perhaps I am not unlike that French youth – you must have read of his sad sad plight – rejected by a circus girl with whom he was in love. A circus girl! I love it. The poor French youth committed suicide by locking himself in the lions’ cage.

I was locked in a cage, tied in a chair, in a capsule’s burning skin, hairline cracks like my mother’s teacup. A rocket standing in a pink cloud and I am sent, her pink clitoris and I am sent, 3,2,1, we have ignition, my missions hastily assembled, mixed up, my mixed feelings as I move, my performance in the radiation and redshift. The officials and women are telling their truth about me. I was thrown like an axe through their stars. I was tied in a chair, a desert, waiting. When the engines power up – what a climb, what a feeling! And who is that third who hovers always beside you, someone near us? When I count there are only you and I together – but who is that on the other side? 1,2,3. 3,2,1.

Why can’t Delia say something passionate to erase my nervousness? I have to live through someone else. Why can’t I be aloof, not care. I used to be very good at not caring. But when Delia hates the moon I feel she hates me, when she says she has no money and that the moon is dirty!, too hot!, too cold!, then I feel I’ve failed her with my moon.

Why does she not say, Come to me my lion, my lost astronaut, I love you more than life itself, my love for you is vaster than the reaches of the infinitely expanding universe, oh I love you so much, so very much. But no one says this. Her expanding clitoris under my thumb. She is calm, she is not passionate. But she is there, I’m happy when she is near. After my trip I crave contact.

I am being straight with you, swear to God. I had a couple of ounces. He was on me – it was self defence.

Did he have a weapon, Delia asks. How can it be self defence if he didn’t have a weapon?

Friends we question say the dead man was always joking, always had a smile.

We were sitting there, the kid says. The gun went off, the kid says, and he fell out.

It went off. Delia tells me they always word it in this passive way, as if no one is involved and, in a kind of magic, the gun acts on its own.

Government people contact Delia. Don’t be afraid, the government people say to Delia, which makes her afraid. They visit her at her apartment, claim they are concerned that a faction in the war at home may try to harm her here.

Has anyone approached her?

No, she says. No one from home.

Has she heard from her uncle in Vietnam? they wonder. Is he coming here?

They were very nice, she tells me, they bought me lunch.

I look at the white business card they gave her; it has a phone number and nothing else. My hunch is that they are Intelligence rather than Immigration. She asks questions for a living and now she is questioned by people who ask questions for a living. Now I worry we are watched, wired, wonder if they hear me massage Delia’s shoulders and her back and below her track pants and underwear, if they hear us joke of lions and tigers.

In the interview room: He owed me money so I hit him with a hammer. He was breathing like this, uh uh uh.

A day here is so long. At Ava’s former apartment building I pick up my old teapot, books, and an end table from the landlord’s storage room. The aged landlord’s stalled fashions, his fused backbone.

“Young man, can you help me with the Christmas tree?”

Of course. I like to help. He was one of the first here.

“The moon used to be all right,” he says. “Now it’s all gone to hell.”

He gives me a huge apple pie from the church bake sale. They attend church religiously, they’ll be in the heavens soon.

And poor Mister Weenie the tenant evicted from his apartment down a red hall.

What was his life like, I wonder, with a name like Weenie?

Horse laughs when I tell them, but Delia doesn’t get the humour.

Now it’s on the books as The Crown versus Weenie. How he yelled in a red hall.

“I belong in there!” he hollered, pounding at the door closed to him. “I belong in there!”

Mister Weenie pounds at doors that once opened for him, and I wonder where we belong and who do we belong with. In times of great stress, says science, the right brain takes over like a god and the left brain sees a god, sees a helpful companion along for the ride, an extra in the party. Does Mister Weenie see a helpful companion?

My ex quit her job to move to Spain. Ava has always loved the sun, the heat in Spain, the food, the language, the light. On a weather map I see that Spain has a cold snap and I am happy, as I know Ava hates the cold. I want her to be cold and miserable without me. I am not proud of this part of me.

Delia reads from a childhood textbook that she found in Ava’s belongings: “Our rocket explorers will be very glad to set their feet on earth again where they don’t boil in the day and freeze at night. Our explorers will say they found the sky inky black even in the daytime and they will tell us about the weird, oppressive stillness.”

“It’s not so bad,” I say. “The stillness.”

“It isn’t at all beautiful like our earth,” she reads. “It is deadly dull, hardly anything happens on the moon, nothing changes, it is as dead as any world can be. The moon is burned out, done for.”

Delia endured a dirty war so I admire her greatly. She gets depressed, refuses to leave her room. Where can she turn? Her Babylon is gone, the happy place of her childhood no longer exists, friends dead or in exile or bankrupt or insane.

My dark-eyed Babylonian love, my sometimes-passionate Persian – where will she move to when she leaves me?

Out the window are astral cars and shooting stars. Where do they race to? I know. I’ve been out there, nearer my god to thee, past the empty condo units, the Woodlands Nonprofit Centre for New Yearning, the Rotary Home for Blind Chicken-Licken Drivers (hey, good name for a band), the Rosenblum Retirement Home (Low Prices and Low Gravity for Your Aching Joints).

My happiest moments with my mouth just below her ample belly, I forget about outer space, her legs muffling my ears, a gourmand of her big thighs, her round hips, surrounded, grounded by her flesh; I have never liked flesh so much as with her. The world only her in those charged moments, my brainstem and cortex and molecules’ murky motives driven by her and into her. The devil owns me. No devil owns me.

The valves on my heart are wide open. I have no defences, sometimes I am overflowing with affection – and I have found this is a distinct disadvantage when dealing with others. I never want this to end; so what do you suppose will happen?

The crowd pays good money to file into the old NASA Redstone Arena, into the band’s aural, post-industrial acres of feedback and reverb. The band used to be someone, now they play the outposts. We are happy to see them here.

The woman singer moans, Don’t you dog your woman, spotlights pin-wheeling in the guitarist’s reflector sunglasses. She sings, I pity the poor immigrant.

We will remember, we will buy t shirts, souvenirs, get drunk, hold hands on the moon. We will remember.

Later the ambulance enters the moonbase arena, amazed in pain and confusion.

The white ambulance takes away one body from us so that we can see and not see. Carbons linger like a love song for all the coroners in the universe. One casualty is not too bad. Usually there are more. An OD, too much of some new opiate, some cousin of morphine, too much of nothing. You pay your money and you take your chances.

Who calls us? The ambulance tolls for someone else. Who owns the night, owns the night music of quiet tape hiss and music of quiet riches and debts in messages and missives from the crooners and coroners and distant stars? I have learned in my travels that the circus girls own the night, and the Warriors and Ghosts and Scorpions run the corner. They have the right messages.

And come Monday or Tuesday the interview room still waits for us, will open again its black hole, its modest grouping of table and walls and the one door. But Delia books off work: the war, the government people, the questions.

Say that one more time?

Who do you think did this?

Dronyk.

Dronyk says you did it.

Who’s bringing it in?

Who. That’s a good one. Who isn’t! Man, who’s bringing it in. Can I have a smoke?

The room – it’s like a spaceship for penitents; we climb in and explore a new universe, their universe. Fingers to keyboard: does he show up on the screen? A hit, a veritable hit, he’s in the system, the solar system.

I don’t want her to worry, but I want to know that she knows.

“Those government people asking you questions; they may not be who they say.”

“I know that,” she says. “I wonder if they are watching us now?”

We watch Delia’s TV. In the upscale hotel room the actor states to the reporter, Friend, for this role I had to go to some very dark places. He was gone for a while, celluloid career gone south, the actor is hoping for an award for this project, a comeback in the movies.

Gone? I’ll tell him about being gone. I went up past the elms and wires, past the air, past the planets. Where did he go? A piano bar, a shooting gallery in the Valley, a dive motel in the wilds of Hollywood? The actor went nowhere.

When you return to a place that is not your home, is it then your home? I insist she go out with me and then I fall into a fight on Buckbee Street in the fake Irish bar (yes, fake Irish pubs are everywhere).

“Hey, look who crashed the party. It’s that rug-rider cunt who sent me to jail.” The slurring voice in the corner, a young man from the interview room.

The brief noise of his nose as I hit him and he folds. Granted, it was a bit of sucker punch. Why oh why didn’t I sprint out of the fake Irish pub at that point? I stuck around to find myself charged with assault. Aren’t you allowed one complimentary punch at Happy Hour?

Now it’s my turn to be asked the questions in Interview room #2. I’ve been here before, know the drill, I know to stonewall, to lawyer up.

What the hell were you doing?

Wish I could help you, Horse. Really do. Beer later? Chops on the grill?

Mine may be the shortest interview on record.

Delia says to me, Stand against that wall. Face forward.

The camera flashes in my eyes.

Now please face that wall. The camera flashes.

After the fight in the fake Irish bar Delia gets depressed and doesn’t want to see me for a week, lunar weeks, it drags on, which gets me depressed that she is depressed in her subterranean room andwon’t let me even try to cheer her up, have a laugh.

“No, I’m in a hopeless situation,” she says on the phone. “I don’t want a temporary solution.”

“Everything is temporary.”

“That is true,” she admits. “Everything is temporary.”

But, I wonder, what of Curtis? Gone, permanent. Ava? Gone. Is that permanent too? I feel myself falling from the heavens.

“Are you hungry? Let’s go out,” I beg.

“There’s nowhere to go here. I’ve told you, I don’t want temporary solutions.”

“Can I come over?”

“I’m tired of questions. No more questions.”

The other astronaut, Curtis – I wonder if I’ll ever know for sure whether it was a malfunction or suicide. Curtis might have tinkered with his air and made it look like an accident, a design flaw, or his air went and it was horrible. I often wonder where I’d like to be buried; perhaps he wanted to die out there. Flight Centre instructed me to tether him outside to the solar array until just before we got back; didn’t want him stuck out there burning up when we made our grand entrance. Maybe Curtis wanted to burn up, the first outer space cremation. It’s almost poetic, but the Flight Centre would not see it as good PR.

You know who strangled the old man? You know who did it? A fuckin stupid crackhead!

He is pointing at himself and in tears. It’s Ava’s landlord who is dead.

I fouled up good, says the aged addict. Using that stuff wore me slap out.

His craggy face. He is sincere, his hard lesson. But he is somehow alive. His prints don’t match his face, but I can read his mind. By the power invested in me. He is thinking like a cheerleader, he is thinking, I must look into the future.

Yes, I tell myself, I too must remember there is a larger world out there, a future. I too must think like a cheerleader.

“This has worked a few times,” my lawyer says before we file into the courtroom. “You guys are the same build. Both of you put on these glasses and sit side by side.”

The judge asks the victim, “Do you see him in the courtroom?”

“He bumped my table, he spilled my drink and then it all went dark. I had a bad cut over my eye. I couldn’t see nothing. Dude was on top of me wailing all over me, and it went dark.”

Wailing? I hit him once and he dropped.

“So you can’t point out the assailant?”

“Hell if I know.”

His girlfriend takes the stand, says, “It might be one of them over there. I thought he was going to kill him, beating him and beating him. I remember the third guy, that tall white-haired feller.”

They cannot ID me. The judge throws out the case, my lawyer makes his money, the truth sets you free.

After my lawyer takes his cut I still have $3000 of the $6000 cash in the paper bag. She’s so sad. Delia saved me, but can she save herself? Delia believes that her God takes care of her. I guess I don’t need to buy a bar in Nebraska. With my cash I buy her a ticket back home to the Hanging Gardens, a visit, but I suspect she’ll stay there or land a more lucrative job in Dubai and never return from the sky.

You are nice, she says.

Because I like you. I like you a lot.

Thank you, she says.

She never says, I like you. Just, Thank you.

The Interview Room is never lonely for long. Who did it? Why? Someone always wants to know. We come and go like meteors, Horse at his desk staring.

That’s the one was running.

Did you see the shooter? Did you see?

I ran off, I didn’t see anything.

No one sees anything.

Why did she leave when I was almost there? Who shot him? Who was the third guy? Don’t know a name. I ran. Give me your money, I heard him say, then Pop pop pop! Man I was gone. No need for it to go that way. I don’t want to do nothing with nothing like that. Maybe Eliot did it.

This is good, this is rich: a collection agency calls my voicemail using a blocked number. The young hireling tries to be intimidating. It may be the loansharks or skip tracers or maybe the poor Burger King clerk at the drive-thru wants his paper bag back.

“Reply to this call is mandatory,” the dork voice speaks gravely on my voicemail. “Govern yourself accordingly,” he says, obviously proud of this final line.

Govern myself? I love that, I enjoy that line immensely, much the way the roused lions enjoyed the French youth’s heartbreak as he walked in their cage, as he locked himself in their interviewroom. You sense someone else with you, you’ll never walk alone, and the empty sky is never empty, it’s full of teeth.

Maybe I’ll re-up, sign on for another December flight, collect some more hazard pay, get away from everyone, from their white apartments and blue eyes and dark eyes. Be aloof, a change of scene; maybe that will alter my luck. I’ll cruise the moons of Jupiter or Titan’s lakes of methane, see if I can see what’s killing the others. Once more I renounce worry! And once more that notion will last about three seconds.

One Sunday Delia phoned at midnight, barely able to speak.

What? I can’t hear. Who is this?

A delay and then her accented Arabic whisper: I have headache.

I rushed over with medicine for her migraines and some groceries, sped past the walled plains and trashed plasma reactors in the Petavius crater. I was happy to rush to her at midnight, happy that she needed me to close the distance.

In her room I saw that she had taped black garbage bags to the windows to keep light from her eyes, her tortured head. I unpacked figs and bananas and spinach as she hurriedly cracked open painkillers.

“Thank you for this,” Delia murmured quietly with her head down, eyes hidden from me. “I know I bother you, but this is hard pain. Every day I will pray for you. Every day I pray the God will give you the heaven.”

—Mark Anthony Jarman

/

/

/