The book’s purpose is not to suggest that language muddies things up permanently; instead, language in Sikelianos’s hands has a fluid quality to it, it has a round-about-ing quality. There is pleasure—and an increased appreciation of the strangeness of words and the power of words – when a reader goes with both the swirl and the forward movement of the river Sikelianos creates.

—Julie Larios

Make Yourself Happy

Eleni Sikelianos

Coffee House Press, 2017

170 pages, $18

.

Reviewers sometimes bite their lips with trepidation when a review copy comes in that has been written by an “experimental” poet. Will the experimental nature of the work in their hands be understandable to someone not fully aware yet of the parameters (the “controlled conditions”) of the experiment? Will the reviewer’s unfamiliarity with the poet’s style, if that style is linguistically challenging, get in the way? Will the knee-jerk desire for a normal narrative line or for easily-absorbed syntactical structures obscure the reviewer’s grasp of meaning? That is, will the reviewer (me, in this case) have the energy and the patience to “get it”?

Eleni Sikelianos is described by critics as an “experimental” poet, but her latest book, Make Yourself Happy, calmed my reviewer-related anxieties quickly. The poems throughout do play around with normal narrative thrust and sequencing, and there are syntactical structures that require a second look, and a slower look. So yes, energy is required. But there is nothing about the poems that provokes impatience, nothing that leaves the reader behind, wondering what just happened. The cumulative effect of reading the poems in sequence, from cover to cover (not something I always do with books of less inter-dependent poems) is inclusive—the poems draw you in one after another, and you travel with them (even the title refers to this second-person “you” engagement with the poet—you are invited to make yourself happy, though you sometimes might mis-define or misunderstand what “happiness” involves.) The book’s purpose is not to suggest that language muddies things up permanently; instead, language in Sikelianos’s hands has a fluid quality to it; it has a round-about-ing quality. There is pleasure—and an increased appreciation of the strangeness of words and the power of words—when a reader goes with both the swirl and the forward movement of the river Sikelianos creates.

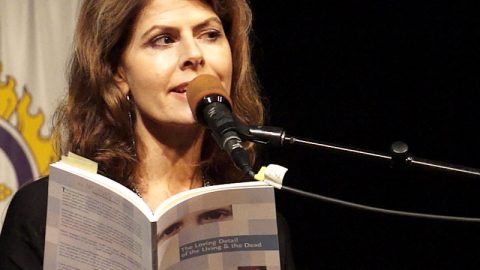

Eleni Sikelianos Reading at Naropa, 2013

Eleni Sikelianos Reading at Naropa, 2013

Make Yourself Happy is divided into five sections, prefaced by a few reconfigured lines from William Carlos Williams in which he chides his readers, “Come on! / Do you want to live / forever?” and ends by calling poetry the art of “listening / to the nightingale / of fools.” Then Sikelianos begins in earnest with the first—and title—section, thirty-nine individual poems—individual, yes, but interconnected by their juggling with and questioning of the word “happy.” The opening poem (“Through the lower window”) ends with this advice: “Get on a donkey / and learn some grammar Get on a donkey / and ride.” Who can resist that imperative?

On second thought, is that advice imperative? The next poem—the title poem—makes us wonder: “We do confuse what is a command and what / a prayer / statement and threat, question / and answer.” So we’ve been warned to be careful, as we read further, about the assumptions we make in our lives: those assumptions might not make us happy. At least, not happy in the way sunlight or a croissant in Paris or butter standing “in a bright rectangle of light” might make us happy, says the poet, nor in the way that the ear “tends to hear what it needs to make itself happy.”

We make assumptions, we create the idea of happiness, we are taught it, sometimes incorrectly. Sikelianos recognizes that we feel happy when we eat ordinary bread, or when we see the buds on the lemon trees. But “Tomorrow / we’ll learn all things to undo in the Making Ourselves / Happy school.” Further along in the first section, at the end of the poem which begins “I had taken the long way home…” , we hear the speaker say, “I would not wish to live anywhere, ever, where everybody’s always / happy.”

A choice must be made between “the pursuit of property or of happiness,” and a difference must be established between relief and happiness. People get confused, they sometimes mistake their privileged status for happiness. So we need to be careful with definitions, Sikelianos suggests. Maybe by doing “nothing fancy” we can make ourselves happy. Or, in the poem that begins “To make myself happy in the face of error…” she admits that the sounds of words can make us happy. “To make myself happy in the face of error I repeat / bandicoot long-nosed bandicoot. You / try it. And see how happy / is the b, the oo.”

It’s clear that Sikelianos—a poet, translator, memorist and professor of creative writing at the University of Denver—enjoys the sound of words, and enjoys the way words themselves seem physical (embodied, capable of movement.) Early on, we begin to hear chiming and rhyming, with the word “ombre” sitting next to “hombres,” and, later, the word “wrist” morphing into “wreathe…wrest…writhe.” Later in the book we hear blue/hue/shoot/thru; in another poem, spare/air/there, and in a poem only six short lines long, we hear softshell, sinner, saved, saved (again), saint and shrine. In the poem which begins “How Happy Are You” (which includes Likert-test boxes measuring our responses to what is being said, from Less True to More True) Sikelianos states, “O how a word can hover in its surroundings between sense and sorrow / a narrow sound shivering / as if the world itself rushed in decay toward that trembling.”

There are many guesses and suggestions in this first section about the how-to of making yourself happy (and about the how-not-to’s.) In the same poem about the sound of the b and the oo, Sikelianos writes, “I look through the pine trees and think / of children who are hungry / somewhere, this poem / can’t feed them. That is not / a right way.” Poetry can’t, of course, become embodied enough to substitute for what materially feeds us. But Sikelianos said this in a recent poem-essay titled “Experimental Life” (American Book Review, July/August 2016):

My concerns now as a so-called experimental poet, are different than they were / …when I wanted to tear everything apart and start anew / …but certainly from when I was dedicated to the poetic performance of language above all else. Now it has come to seem that culture-making and art-making are preservationist acts / For salvaging some thinking and feeling among the tatters.

Poetry can, she suggests, matter. It is a “sensory remnant, as if we could still taste it on our tongues.” Sikelianos recognizes “the tatters” that exist, and she commits herself to examining how to live as a creative person in that kind of world. Further into the ABR essay she says this about life (“animation,” we are told, is the word Aristotle used):

…to consider only material in the abstract (like capital or language) / Is a way of reducing us to bare life / But to consider material’s animation, its movement and interactions / Means to take spiritual, emotional, political, personal and material risks in the poem / And these things (we will call them) together are what make context / (from the Latin: to weave together) / Which is a way to live in the world

For Sikelianos, happiness seems to mean that a way has been found to salvage thinking and feeling and to establish context. As a poet, she must work to “animate” language, to weave what is material with what is abstract, and to take risks with words. She enjoys “… the sound of each word rubbing up against the others / The rhythm of each jostling in its context / Rhythm being one of the things that animates the living.”

As she says in the poem that begins “One Way,”

a fuzz of white pine sapling says yes yes

in the wind then

no, no! when it says yes

and when it says no make a

go of

it. It

is how to live.

We must do our best to make a go of it, she suggests, just like the pine saplings do. And one of the tools poets use to do their best is language. Of course, language can be a fierce wind, too, blowing on those saplings: “Gustave Flaubert’s father / had a voice like a scalpel, able / to skin the feeling right off / the surface of the body.” We hear another warning: Be careful not only with definitions but with words themselves.

As the first section proceeds, it becomes clear that Sikelianos is interested in dichotomies—life/death, inside/outside, money/honey, green/grief (“coming to be” and decay), the natural world / the constructed world. This interest becomes even clearer in the second section of the book, titled “How to Assemble the Animal Globe,” which consists of thirty-one poems divided into seven sub-sections, all relating to extinct species (“lastlings”) on seven continents, all the extinctions due directly or indirectly to human action / inaction. This is the natural world vs. the constructed (man-made, man-destroyed) world.

The poems in this section contain many lines of encyclopedia-like information about the animals. For example, these lines about the Bubal Hartebeest of North Africa: “…when viewed head-on, the horns / formed a U; the last captive female. died November 9, Jardin des Plantes, 1923.” I can find no poetic language, only information, in the poem about the Tasmanian Tiger. But many of the poems in this section also break into lyrical passages, like the poem about the Mauritius Blue Pigeon which ends with a ship’s artist who “up in the river gorges, saw / the plucked earth coming”.

There is a whole song of extinction in this section, as well as several small, haiku-like poems. About the Pied Raven, Sikelianos writes “over hill and dale the only thing moving / like a riddle a raven/ is as little in its yellow eye / as mine.” A poem titled “Great Auk” uses alliteration with abandon (beautiful / bird / bizaare / burning / burning /body’s / buried / bones / beaks) and tops it off with clever near rhymes: auk—skin / auction / unction. It’s a pleasure to see the poet enjoying the tools in her toolbox.

Two poems (“For You to Write About” and “Lost and Found (Lazurus Species”) do what many great poets love most – they name things. These two lists of extinct animals beg to be read aloud, with names that roll around on the tongue: “Broad-faced Potoroo / Darling Downs Hopping Mouse / Crescent Nail-tail Wallaby / Pig-footed Bandicoot….” In a footnote to the Lost and Found poem, we learn that the Lord Howe Island Stick Insect was also known as “the walking sausage or the land lobster.”

The fourth section—a 34-page poem titled “Oracle Or, Utopia”—charts a path through the jungle of man’s abuse of the planet (“…what it means to be live alive, when the world made its first sounds / …what it means / to be gone agone) and the possibility of weaving one world from the previous two (man/nature or past/future.) Of course, nothing about this path is easy; “Utopia” is an imagined place, and an “oracle” is a prophecy with ambiguous meaning. The section focuses on the future, but it sneaks in lines like this: “Then if the past / comes bustling in like a band of cocked revolvers…” Trying to determine how the past and the future can flow together smoothly, with “all the pictures moving forward and back / the old rock dust and the new new planet” involves poetry, which can move between “rupture” and “rapture.”

“Is There a River Here / Epode,” the fifth section, offers up a lovely 2-page poem ending on a welcome note of optimism, as does the sixth and final section, “There Were Ancient Questions Inside My Head (Rider.)” Added after the last poem are fascinating endnotes—often expanding on scientific principles mentioned in the book—and acknowledgements for the many images used throughout.

For readers of Numéro Cinq who shy away from experimental writing, I encourage you to give Make Yourself Happy a try. Consider the words of critic Warren Motte, who said this in his essay titled “Experimental Reading”:

[T]he experimental text involves us, enrolling us willingly or unwillingly in the process of textual production, and enfranchising us in that process as full partners. In the first instance, it may shock and bewilder us insofar as it beggars traditional, normative strategies of reading and interpretation. Yet by the same token, it grabs us and demands a reaction from us; it engages us and insists that we do something with it; it rejects outright a passive reception in favor of an active, articulative one. …Experimental writing obliges us to read experimentally….

We go at the experimental text hammer and tongs, gradually realizing that the text has been conceived with that very process in mind, and that in fact it anticipates our interpretive efforts. In other words, whatever else the experimental text may speak about…it also (and crucially) speaks about us, and about our efforts to come to terms with it. Moreover, it addresses that speech directly to us, in an unmediated manner—just as if it were inviting us to engage in a conversation….

This is the conversation Eleni Sikelianos invites us to in Make Yourself Happy. She starts the conversation by asking us what happiness is, and though she doesn’t feed us answers, she closes the conversation six sections later with these lines:

Of happiness, what have we lost? What wilds it?

My loves

I call all

of you.

Here, I want you entirely happy.

—Julie Larios

Note: The poet – whose poetic voice is generous and inclusive—also generously responded to questions for a Numéro Cinq interview running concurrently with this review. You can link to her responses here. And you can read two of the books poems (“Making the Bird Happy” and “Do Nothing Fancy”) in their entirety here, with thanks to Ms. Sikelianos and Coffee House Press for their permission to reprint these poems from Make Yourself Happy.

N5

Julie Larios is a Contributing Editor at Numéro Cinq. She is the recipient of an Academy of American Poets prize and a Pushcart Prize, and her work has been chosen twice for The Best American Poetry series.

N5