x

x

The Tin Palace was a seminal place for jazz in the 70s and many well known figures today came up from the grass roots of that space. Paul Blackburn was a core figure in the poetry world of that time. The essay doesn’t belabor those points, but is focused on the mystery behind the history.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx—Paul Pines

x

1. Intimations

Along with Dick Tracey’s two-way wrist radio watch, and Captain Midnight’s decoder ring, invisible ink highlighted the mysteries of my Brooklyn boyhood. The idea that unseen writing might surface with the heat of a flame held under the page was irresistible. I experimented with different solutions, like milk and vinegar, in an attempt to duplicate the process. Unhappily, little more came of these experiments beyond the flaming napkins in my hand.

My fascination was ignited again during hormonal teenage summers cruising the beach that ran along the southern hem of Brooklyn from the elevated BMT subway stop on Brighton Beach Avenue, all the way to Sea Gate. My crew roamed between the parachute-jump, rising like an Egyptian obelisk from Luna Park, to the fourteen story Half-Moon Hotel. Both loomed like thresholds at the edge of the known world. The haunting quality of the place was especially palpable in the shadow of the Half-Moon Hotel, where Abe Reles, as FBI informant guarded by six detectives, jumped or was pushed out the window on the sixth floor. Reles had already brought down numerous members of Murder Incorporated. His defenestration occurred in 1941, the day before he was scheduled to testify against Albert Anastasia. The hotel’s name echoed that of Henry Hudson’s ship, which had anchored briefly off nearby Gravesend Bay, hoping to find a short cut to Asia. Folded into the sight and smell of warm oiled bodies on the beach and under the boardwalk, past and future pressed hard against the flesh of the present.

Luna Park by Marc Shanker

Luna Park by Marc Shanker

Nowhere more so than at Brighton Private, a pay-to-play beach club bordering Bay #1, one of fifteen numbered sandy plots along the Coney Island peninsula. Brighton Private aspired to the kind of exclusivity prized by the elite in Long Island or Atlantic City, but on the more modest basis of a daily entrance fee, as well as by subscription for those who rented lockers by the season. It offered a pool, steam room, cushioned lounge chairs and a superior cruising ground for boys in heat. Those inside could come and go to the ocean through a beach-side where the gate-keeper stamped the hands of members with a waterproof mark visible under a black light.

My crew from lower Flatbush devised a strategy for entering from the beach. We put together enough money for one person to get in, change into a bathing suit, and exit on the beach, his hand freshly stamped to validate re-entry. His mission was to reach the rest of us waiting out of sight, under the boardwalk, in time to impress the still wet stamp on our hands. This was not without an element of risk. Just as often, the mark got smeared or devolved into a smudge. At one time or another, we all had experienced the humiliation of being unmasked by the black light, and fleeing the consequences if caught.

.

2. The Call

Before I opened the doors of my jazz club, the Tin Palace, the situation rang a bell that raised the memory of Brighton Private. I realized that there had to be a way of marking the threshold between that interior space built so lovingly and the war zone outside. Bowery and Second Street had been a no-man’s-land inhabited by winos, fleabag hotels, and those who spilled out of the Men’s Shelter on 3rd Street every morning. Then there were the predators who preyed on them, jackrollers from Alphabet City drawn by the monthly mailing of welfare checks, as well as junkies looking to score. It was also a deep underground network of creative energy. Artists’ lofts lined Bowery all the way to Chinatown, poets occupied the tenement hives and storefronts on the Lower East Side, and jazz lofts seeded by musicians sprang up like wildflowers on the side streets. My partner and I staked out our territory for the Tin Palace on the corner of Bowery and 2nd, transforming the burned-out husk of a bar into an oasis. Our interior featured walls taken down to the brick under a pressed tin ceiling, an art deco mahogany and rosewood bar, cocktail tables and a small stage for musicians. In the years that followed, I heard nightly improvisations that transported the entire room into another dimension, unfolding at the outer boundary of the cultural mainstream where survival is often “writ in tooth and claw.” From the start, I understood that such a space as we had made required its own rules and rituals, a way to make the mystery of its existence palpable to those who entered it. I settled on the idea of a rubber seal dipped in invisible ink made visible under a black light.

Tin Palace entrance by Ray Ross

Tin Palace entrance by Ray Ross

In August, 1972 there was only one listing in the Manhattan Yellow Pages for Invisible Ink. I traveled up to 23rd Street and walked that long stretch between Third Avenue and the tenement facing Madison Park in the shadow of the Flatiron Building. An elderly male voice responded to my signal on the buzzer asking what I wanted.

I answered, “Invisible Ink.”

The face that greeted me at the door at the top of six flights of stairs filled out the picture.

The Invisible Ink Man had been taller in his youth, his back now bent at an angle that reduced him by a couple of inches. A cloud of white hair circled his head, and frown lines framed a kind but expressionless face, as though hinting at the unseen interior. He wore a white shirt with sleeves rolled up to his elbows and brown pants. The room I entered was dimly lit, flanked by long tables cluttered with newspapers and magazines. There was a living space at far end, a round table circled by folding chairs, a couch behind it. He apologized for the appearance of his digs, letting me know the obvious, that he didn’t receive many visitors these days. His face brightened, and he seemed to straighten out when I told him why I’d come.

“I can customize the stamp to your design,” he told me. “Do you have something in mind?”

I emphasized that this stamp would operate at the gateway of two worlds, and wondered if something Egyptian, The Eye of Horus, or maybe Hermes’s winged sandals that allowed him to move between worlds. The Invisible Ink Man nodded, thoughtfully, before saying he had books of designs if I wanted to look through them. He then went on to reminisce, letting me know that his had once been a burgeoning business. The call for his product had kept him busy with orders from all over the world. He had been a craftsman, reaching for a high bar with the quality and power of his designs. Now, he was the last of his breed.

Apollo pouring a libation to a blackbird

Apollo pouring a libation to a blackbird

“Let me think about what I want,” I hesitated.

The Invisible Ink Man replied that would be fine. When I asked if there was a bathroom I could use before I left, he pointed to a door behind one of the long tables. It was a small room with a pull chain bulb that illuminated a veined marble sink and a vintage toilet crowned by a wooden thunder box. Tucked behind the pipe leading up to the box, a poster with the Day-Glo figure of a man half-way into a toilet, his hand on the pull chord of a chain such as I held, spoke through the inscription, “Goodbye cruel world.” I pulled my chain to the thunderous applause of water from the tank above the toilet. The Day-Glo figure remained. I wondered if he expressed something unseen in the Invisible Ink Man, what would emerge from my host’s interior under the appropriate x-ray.

The Invisible Ink Man walked me to the stairs. He assured me that if I got back to him in time, he would make me a stamp for the ages and provide me with a generous supply of ink in the invisible color of my choice.

.

3. Collapsing time

Walking on 23rd towards 5th Avenue, I stopped at an empty parking lot. On another mission, a few years earlier, I had seen the poet Paul Blackburn standing in that lot, head tilted, looking at something that had caught his eye.

“There was a building in front of this one.” Paul said when I joined him. “Sarah and I lived in it.”

“And now it’s gone.”

“I can still see the room where we made love, the view from the window.”

Cornelia Street 1922 by John Sloan

Cornelia Street 1922 by John Sloan

He stared intently, as though what he described was still going on in that space, time out of mind. There were few poets more alive to the sights, sounds and feelings rising from a unseen source, images becoming clear under the ultraviolet glow of his imagination. Paul moved between visible and invisible worlds, like Hermes, but wearing a cowboy hat instead of a winged helmet. Through him I became aware of poetry not only as art but as physics—or in the words of Ervin Laszlow, a place where field precedes from. His poems formed themselves on the page like the incarnate nervous system of the experience he brought to light, a design specific to it, but inevitable. Paul’s fields invited oracular, synchronistic, spooky action at a distance, while cleaving to the physical details. As he wrote in his poem “The Net of Place,” The act defines me even if it is not my act / The hawk circles over the sea / My act…

When I encountered Paul in the parking lot gazing at the invisible space which once contained the apartment where he and his second wife, Sarah, had made love, I was reminded of the mystery that sustained him and his work, to which I aspired in mine: to capture in that net the energy patterns that are so immediately present to the senses, but exist outside of time as well. The net of place contains both visible and invisible worlds. Or, as Paul put it at the conclusion of his poem: When mind dies of its time / It is not the place goes away.

Angel: New Orleans by Paul Pines

Angel: New Orleans by Paul Pines

Clearly, Paul, who died in 1971, had also been my Invisible Ink Man.

My desire to realize the forms inherent in the field of my own experience, moved me to ask him if he would write an introduction to my first collection, Onion, forthcoming from Mulch Press. I’d already encountered resistance from the literary gatekeepers. They would not stamp my hand. I felt so much rode on Paul’s blessing.

He wrote three introductions, which I rejected. Each one fell short of what I had hoped for, something worthy of what I reached for. I had counted on a certain gravitas that was not there. One of his introductions described me as a small man walking a large dog down Second Avenue, reveling in his world. It was full of an affection I didn’t get at that time. The image of me as presented was accurate, even vivid. I may have glimpsed as much, but couldn’t bear it.

Onion came out the year Paul died, 1971, with no introduction.

Twenty years later, preparing to read at a tribute to Paul in St. Mark’s Church, I searched his Collected Poems for a poem I loved, “Cabras,” about goats in the next field hobbled because they are otherwise difficult to catch, but remain “so quick, stubborn / and full of fun.” It reminded me of Mallorca, where we had both lived at different times. And about ourselves, in the respective fields of our callings. As I leafed through the thick volume of Paul’s collected works I stumbled on lines from his Journals that sent a shock through my system, and then left me in shaken. They had been sent silently years earlier, but heard first in that instant. Paul’s final message to me once again collapsed time.

xxxxxxxxHow can we

offer it all, Paul? How

ignore the earth movers . will

take it all down?

.

4. On the threshold

I never saw the Invisible Ink Man again. I did manage to get a stamp, invisible ink pad and a black light stationed at the entrance to my Bowery jazz club. There was nothing designed to order, and after a while the process became too slow and unreliable. But I did come away from my journey to 23rd street that day with a greater appreciation for the mystery I felt on the threshold of that door separating the interior of the Tin Palace from the world outside of it, what I thought of as my Camelot, a moment of light in the dark. The fact that that my light burned brightly for the decade, then went out, gave me a deeper understanding of the field from which such forms arise and dissolve.

Outside the Tin Palace, 1976 (courtesy Patricia Spears Jones) clockwise: Stanley Crouch, Alice Norris, David Murray, Carlos Figueroa, Patricia Spears Jones, Phillip Wilson, Victor Rosa and Charles “Bobo” Shaw

Outside the Tin Palace, 1976 (courtesy Patricia Spears Jones) clockwise: Stanley Crouch, Alice Norris, David Murray, Carlos Figueroa, Patricia Spears Jones, Phillip Wilson, Victor Rosa and Charles “Bobo” Shaw

Invisible Ink is a metaphor for a narrative already written that in the heat of time will emerge to be read as destiny, history, or memory. I track this in my own experience to the Invisible Ink Man and his thunder box toilet, Paul Blackburn reliving his intimacy with Sarah in the empty parking lot, and my moment beside him wondering at the invisibility of it all. The Greeks thought of their underworld as a place where hidden treasures were stored, and it is easy to conflate those with memories that are eternal and continuous.

What I contemplate still at the entrance to my own underworld.

All thresholds are essentially boundaries between the known and the unknown. One enters a jazz club from the street to call forth invisibles not available elsewhere to the eye and ear, the audible changes that disclose hidden places. Often these are places known and forgotten, and now known again in a way that changes everything.

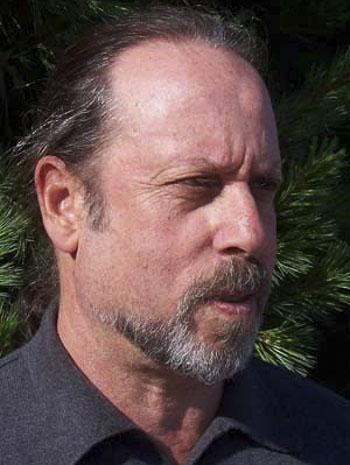

Paul Blackburn by R.B. Kitaj

Paul Blackburn by R.B. Kitaj

I am certain that there is a connection between the moments in my life when someone stamped my hand with invisible ink that can be seen under a black light, and the initiation into a mystery as old as Eleusis—the veils of Persephone, and Isis. I consider what took place at the Tin Palace, beyond the big oak doors on the Bowery, and why Paul Blackburn haunted The Five Spot, followed the improvisations he heard, and reproduced them on the page. I remain fascinated in a childlike way; I wanted to possess Captain Midnight’s decoder, the latent, undisclosed landscape of potentials, things in their nascent state on the way to being realized. In this pursuit, earlier guides like Toth, Hermes, and Telesphoros, now have names like Monk, Mingus, and Coltrane. Paul Blackburn died before I opened the doors to my club, but I’d like to think he would have been at home there. We shared a desire to hold the heat of our attention to the page of a given moment and watch what had been written there unseen, emerge into plain sight. It draws me still. And Paul, as I imagine him, tuned to what emerges from the implicate order on the other side of that threshold. He was, after all, no stranger to the kiss of invisible ink.

—Paul Pines

x

Paul Pines grew up in Brooklyn around the corner from Ebbet’s Field and passed the early ’60s on the Lower East Side of New York. He shipped out as a Merchant Seaman, spending August ’65 to February ’66 in Vietnam, after which he drove a cab until opening his Bowery jazz club, which became the setting for his novel, The Tin Angel (Morrow, 1983). Redemption (Editions du Rocher, 1997), a second novel, is set against the genocide of Guatemalan Mayans. His memoir, My Brother’s Madness, (Curbstone Press, 2007) explores the unfolding of intertwined lives and the nature of delusion. Pines has published eleven books of poetry: Onion, Hotel Madden Poems, Pines Songs, Breath, Adrift on Blinding Light, Taxidancing, Last Call at the Tin Palace, Reflections in a Smoking Mirror, Divine Madness, New Orleans Variations & Paris Ouroboros and Fishing on the Pole Star. The last collection won the Adirondack Center for Writing Award as the best book of poetry in 2013. Poems set by composer Daniel Asia appear on the Summit label. He is the editor of the Juan Gelman’s selected poems translated by Hardie St. Martin, Dark Times/ Filled with Light (Open Letters Press, 2012). Pines lives with his wife, Carol, in Glens Falls, NY, where he practices as a psychotherapist and hosts the Lake George Jazz Weekend.

x

x

Damn, Paul, that was moving & nice…..