The doorbell rings for the second time today and only the second time since he moved into the condo a month ago. He opens the door to a slender woman in a sleeveless shift of pale color and pattern.

“You got my card,” she says, politely, though with some insistence.

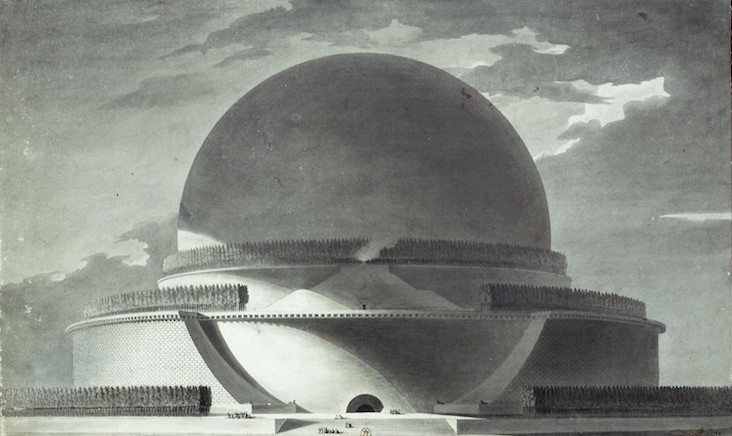

The first time the bell rang was this morning for delivery of a print of Étienne-Louis Boullée’s cenotaph, which he hung in the landing of the stairs he just descended, now hovering above, behind him, a huge dark sphere against a dramatic sky, set on a massive circular base.

It is August and it is hot, pushing a hundred at least. It’s the kind of heat that slows thought and melts reserve and makes you aware only of the present moment, the only apparent truth of which is that it is hot. There is, however, a faint breeze.

“Yes,” he says but doesn’t know what she means though feels he should. Somehow her flat question, like her unexpected appearance, feels related to the heat.

She explains. She is a real estate agent who is looking for sellers so she can find buyers.

Now it makes sense. Actually he has received a dozen cards with the same request but doesn’t tell her. He doesn’t remember hers, however, though her picture must have been on it. He tells her he has just moved in so isn’t interested in selling, but instead of motioning towards parting he rests. He’s not eager to go back upstairs where it is hotter.

She lingers too, listing in the heat with weight on her left foot and head to the other side, creating slight asymmetric angles that show in folds down the looseness of her dress. She is quite young and likely new to real estate, likely indecisive and uncertain, perhaps a bit afraid. Plain, with auburn hair that falls to her shoulders and a long face that does not promote or defend, she has a quiet presence that appeals to him, an unstudied grace.

Actually she’s rather pretty.

But it’s the tattoo that holds him. It runs from her wrist up her right arm, covering it wholly, and disappears into the shoulder of the dress, a complicated design in fresh, bright colors he cannot make out in a single glance. Flowers, at least, but more, and it’s too involved to find attractive. He avoids looking, and it’s the not looking that locks him in its grip. Not that he hasn’t seen tattoos before. They are part of the cultural landscape. But now they are everywhere. This is Portland.

The sky is clear and bright, contradicting the clouds and drizzle he was led to expect. If he was high enough he could see the sharp, snow-streaked peak of Mount Hood starkly rising above flat Oregon. But the sky, like the heat, feels permanent and absolute, as if there never was and never could be any other kind of weather.

A cenotaph is a monument honoring a person whose remains lie elsewhere, in Boullée’s case Sir Isaac Newton.

“Two bedroom?” she asks.

“No, three.”

And he explains the layout of the complex, some twenty independent units, each with six condos, that line one side of a long block, turn at the end, and return down the other side, making a U with an open court and drive in its middle. Two one-bedroom condos on the first floor front the streets, with two two-floor three-bedroom above them. Two two-floor two-bedroom at the back sit above the garages and face each other and the court.

She takes all this in.

The architecture is modern and distinctive, with odd angles and gray and muted orange and blue planes arranged in a varied but subdued design that makes a relaxed yet orderly procession down the street and around the U within. He rather likes it. Landscaping is obviously done on a budget, but it is interesting, with many plants and trees he does not know.

Circling the cenotaph on three levels, cypress trees, symbols of mourning, tightly spaced.

Would she like to see the place?

There can be nothing suspicious in his offer. He has two daughters, older. She must be able to see him for what he is, a man in his early sixties with some refinement, scarcely imposing. He does have a motive, however. He is curious if he got a good deal on his place and wants to know where the neighborhood is headed. Now it occurs to him he wants to help her. She has stiff competition, and he might be able to give her an edge.

Actually he has no idea how he looks. He is sweating down his face and has dark circles in the armpits of his t-shirt. He hasn’t shaved today and must look haggard and maybe something else he cannot see but suspects. Then there is the feeling he does not voice in his thoughts, that the heat has brought out what and who he actually is, which, again, he cannot see.

It is the effect of the heat, that it dissolves illusion and reveals actuality, or seems to.

She would, and she takes off her shoes and he lets her go first and watches her ascend with speed and resolve that surprises him, then follows her up into the rising heat. She stops at the print, pauses and stares without comment, then turns and gives the room the same look, curious, taking in, not judging.

The layout is open, a large room with space for cooking, dining, and living, plus a small recess to the right next to a door that opens onto a small porch. The open plan, he thinks, has become a cliché, whose inspiration has been lost in years of unexamined accommodation. But the space is interesting, with a tall ceiling cut by the visible diagonal ascent of the stairs to the three bedrooms above. He has divided the space with low bookshelves in a loose cubist design. Much is in place, much still has to be resolved. The room should work for the new life he envisions.

But even though the windows are wide open the air is still, and with the blinds drawn the heat has turned dark in the shaded room, making his plan look static and confused. Yet she walks about, studying space, taking mental measurements and reassembling, tentatively but with an easy acceptance that puts him at ease.

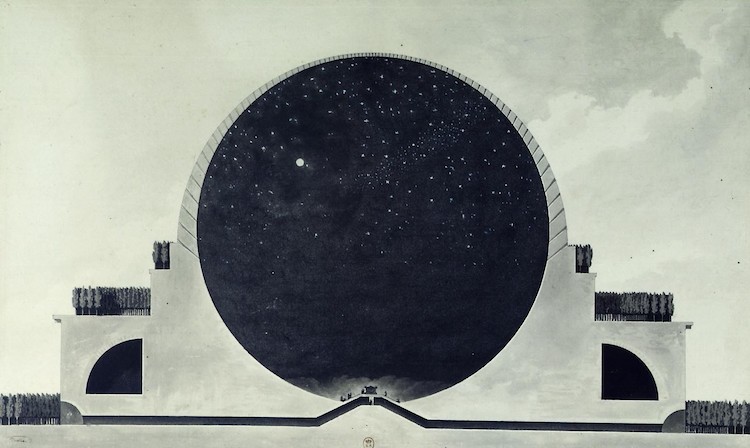

The scale of the cenotaph is enormous. The sphere has a diameter of 500 feet and human reference is nearly lost. Broad stairs lead to entry through a round opening, large yet small compared to the sphere, which dwarfs. Then a long tunnel leads to the interior where there is only the vacant sarcophagus, in the center, and vast, empty space.

Holes are cut in the exterior to simulate inside the points of light of stars in the universe, the interior otherwise dark and seemingly without end.

At night a central hanging light illumines.

The cenotaph, however, was never built.

She puts a hand on the closet door beneath the stairs, stops, turns, and gives him a raised-eye look that asks may I, and he replies with a wave that says by all means. She flicks the switch and looks inside, then extends her exploration further, gaining momentum, as she studies the fireplace, the moldings, the windows, the fixtures, the recessed and suspended lights, the appliances, and the many kitchen cabinets, which she tests and opens—most empty. She has an obvious purpose, yet there is a quiet mystery about her look, her movement as she inspects, that is not mysterious.

She reminds him, actually, of Portland. The people are friendly and supportive, and it is easy to talk to strangers. When he steps out on his porch, passersby look up and say hello. If it is morning, they say good morning. They don’t let their guard down because they don’t have one up. Many walk dogs, who also have a friendly face. They accept you for who you are, or don’t make distinctions. There’s a civility, even, in their advertised weirdness. The city itself shows it cares.

He wonders if Portlanders lack drive and sharpness, and feels superior to them, an attitude based on nothing, that he’d better get rid of quickly. Perhaps it is a matter of priorities. Many he’s run into are feeling the pinch, however, especially from housing, which has heated up the last years. Yet they take things in stride and remain upbeat, though he sees hunger when they conduct business, restrained but gently aggressive.

Then there are the tattoos that he sees everywhere, on everyone—skulls, demons, and monsters; crosses and ankhs and stars and circles of yin and yang, and cryptic words and unknown names; mythological figures across time and from around the globe, and gangsters and saints and comic book characters and common faces, also unknown; roses, vines, rocks, trees, waves, and celestial bodies; geometric figures and crude scrawls; chains, barbed wire, and enclosing arabesques; erotic poses and sudden gestures—tattoos that cross the lines of race and gender and class and age, that cover entire bodies, the hidden parts revealed in open blouses, a hiked skirt, a flapping shirt, a pants slip at the waist, a chaotic language spreading like a contagion, or like an efflorescence.

But they wear their tattoos with composure, an apparent not knowing they are there. Do the tattoos reveal a brooding darkness within, the possibility of excess or dissolution, waiting to emerge? Or do Portlanders place those doubts and fears and desires on the surface so they can get on with their lives, maybe even enjoy them?

And there’s still more, catalogs’ worth, more signs and images and patterns that push context and recognition, as if Portland is trying to expand common language and go beyond—or exhaust it?

Is this madness or transcendence?

Or both?

Or neither?

Do tattoos have to mean anything?

Does anything have to mean anything?

But what does he know. He’s only been here three months.

He gives her arm a few quick looks as she circles the room. Eyes among the bright colors, animal he thinks.

She completes her tour and comes to the kitchen counter where he stands. He wipes his brow with a handkerchief. She follows with a hand. Bottled water is offered and accepted. She takes a long draw, and his throat feels the water go down hers.

Again a pause. He doesn’t want to see her go and she isn’t in a rush to leave.

This is not the time or place for life stories. She’s young and he doesn’t want to pry. Nor does he want her be anything other than what she appears to be, a woman finding her way, on her way up. His daughters, one in New York, one in Boulder, both are having problems, two different sets, and there’s nothing he can do. Likely she has just seen all she needs to know about him and can tell by what is missing, that he is an aging man on his own, nice enough, with some interests she may or may not find boring.

As it is there’s not much he wants to say about himself, or can. He is—or was—an architect for a large firm with a reputation in San Jose that has had several scores with the tech industry. He entered work with goals and with passion, but those dissipated over the years in the long hours, the manic schedules, the endless compromises, the suspicions, the not talking among his superiors and colleagues beneath the veneer of the firm’s professed creative community. He wasn’t especially proud of anything he did nor felt he made any dent in the architecture there, construction that looked forward without looking at anything, buildings without identity or architectural distinction. Above, beyond, or somewhere, the invisible spirit of Silicon Valley, its ceaseless wonder.

His marriage followed a similar course, more or less.

Now he doesn’t give either much thought. There is too much that is too tangled, too indistinct, and little that might carry over. Resurrecting those years would only get him lost again. No thought of starting over again in either. He’s too old and doesn’t want to go through the process again.

Boullée was the son of an architect, a brilliant student who went on to teach and become a first-class member of Royal Academy of Architecture in Paris, who had clients among royalty and the wealthy. It is late eighteenth century. Neoclassicism is in full bloom and ideas of the Enlightenment are in the air.

Names have not been exchanged. That moment has passed. He still has questions to ask, however, before she leaves.

What would his condo go for now?

She smiles and gives a number in the ballpark of what he paid.

Does she think that price will hold?

She hesitates, but says it should go up.

What does she think about St. Johns?

She loves it.

St. Johns is a neighborhood north of and out a bit from downtown Portland, once working class but now, as real estate agents say, up-and-coming. When his agent showed him the place he jumped on it, padding his bid.

After the divorce he rented a townhouse in Sunnyvale that he hated. Last September his landlord gave notice so he could sell, plunging him into a housing market that had once again exploded. Rent for comparable space was twice what he was paying or, if on the market, houses like his were going for well over a million. Nothing was in range, nothing looked good, everything was bad fifty miles out. It made no financial sense to stay there. He had no close ties. He might as well leave and retire.

He had no idea where to go.

He didn’t want to return back east, a forty-year-old memory almost lost. Most of his family were gone or had scattered, and he didn’t want to brave the winters again. Some urban areas were depressed, most were difficult and hopelessly out of reach. Small towns lost appeal when he looked closer. Retirement communities depressed him. He spent weeks studying online real estate listings and making virtual tours with satellite maps and street views, and what he most saw was what he already had in the Bay Area but had put out of mind, the sprawl of suburbs, everywhere, further out than he realized and still spreading, all of it the same. There wasn’t a good place to live in this country.

Portland is a great town, his friends said. Go to Portland. Late one night, after a week online wandering its streets, he committed without even flying up. It looked affordable and interesting, with much going on. At least, with its oddness, he wouldn’t feel out of place. Most, he saw no other options. He knew no one there.

The route that took him to Boullée was even less direct. Two weeks ago another online search, whose object he has forgotten, took a wandering path, impossible to trace now, and landed on the image. He recalled seeing it in a history of architecture class, back in school, decades ago, struck then by its boldness, its simplicity. Memories and desires surfaced and filled the huge sphere. It signaled a fresh start and possibilities, a future. He found a print online and ordered on the spot.

St. Johns looks iffy, he says. Many of the shops and bars and cafes are struggling.

They have been here for years.

These prices can’t last, can they? Why isn’t this market another bubble?

Another downturn and he’s lost money and is stuck for years with a place that will not move.

She doesn’t respond.

Real estate in Portland was a trauma from which he is still recovering. When he arrived April inventory was at a historic low. Places he saw last September were going for fifty thousand more and got snapped up in a few days. He had fifteen minutes to look, then had to make a bid the next day against other buyers. He felt he had fallen through a crack.

Where are all these people coming from?

He knows the answer in part—California.

She shifts her weight to her right foot and turns her head to the left, again sending angles down her shift.

None of the options were right, and he looked everywhere, downtown, at all the neighborhoods surrounding. Skinny infill houses, condos too basic, dubious construction in both, studios impossibly small. Locations too rough or too remote or both. The better condos and the Craftsman homes that give Portland its character were too risky for his reserves. Still he considered each, thinking about a possible life and trying to make it fit, but saw it shrink or tear apart as he imagined the sacrifices and compromises. After two months of running up hotel bills he thought he’d have to bail out. Then what?

How are people making it?

The numbers don’t add up. Income is not that high here. Something has to give.

Is Portland going under?

What most got to him were the homeless, and they were everywhere. Their tattoos, the unhealing sores, the embedded dirt, the streaks of vomit on the sidewalk, the bottles, the hidden needles. Their withdrawal, their hermetic possession, their unconscious states—yet they seemed to own the streets. If he caught their eye they returned a black recognition he could not deflect and still cannot shake. Homeless were better hidden in San Jose.

She shifts to the left foot and realigns, her long face twisting with an anxious thought.

He has gotten carried away and sees he is troubling her. His agent couldn’t answer his questions either.

“Portland is a great town,” he says.

She smiles again and straightens. She has a sweet smile that doesn’t melt his heart but glides through it.

“Where is—” she asks.

“Upstairs. Through the front bedroom.” Better upstairs for privacy.

“Feel free to look around.” He thinks his bed is made and clothes are off the floor, but can’t remember.

He watches her rise, seemingly weightless, her bare feet soundless on the carpet, her shift ascending like a spirit.

O Newton! With the range of your intelligence and the sublime nature of your Genius, you have defined the shape of the earth; I have conceived the idea of enveloping you with your discovery. That is as it were to envelop you in your own self.

Boullée says about his cenotaph in a treatise.

Newtonian physics still works and explains most of our lives day to day. But the cenotaph was never built because the monument was, practically, unfeasible. Boullée was a visionary.

Actually the front bedroom is his office. He has already begun work—quick sketches on the walls of a school, a housing complex, a museum, a community center. On a table, assembled blocks of wood and cardboard scraps and wads of crumpled paper, just to give him a rough sense of texture and form. He wonders what she makes of it.

His projects, of course, will never be built either. He is out of the profession now and lacks the means and clout. Still, they might provide him with a virtual world to replace the one he has left, restoring, creating what it missed, a place where he might feel at home.

The cenotaph didn’t look right the moment he put it up, however, and his impressions, along with his mood, have been pulling away from it all day, and they return now and start to take form—profoundly mysterious, deeply absurd, or downright silly—but these shift to other thoughts and moods that do not settle either but take him to a single thought:

It his hot.

He stares at the room, at the open pattern of the bookshelves, and watches his plan fall apart.

The toilet flushes.

The animals on her arm, he realizes, are dragons.

In Boullée’s time there was a belief in reason and basic truths and the truth of basic forms, in orderly fitting together of parts, the power of architecture to reform.

The French Revolution was around the corner.

Has Boullée taken Neoclassicism to its logical culmination? Or is he trying to look past? Or has he, unknowingly, trapped in its assumptions and contradictions, pushed those into tumescence? Postmodernists took a liking, for a while.

His world is a mess. Beneath all the exuberance the signs on all fronts are bad. In architecture everything built now is glass and steel and grassy planes and white walls, pure abstractions making the same blind projection, covering the the same confusion.

There are other things he sees now, coming into focus.

He has no idea where he has been or where the world is headed. If he hasn’t recognized it before it’s because he has only been busy and distracted the last forty years.

Most of the crumpled papers on the table in his office are rejects. His projects will never get built because he doesn’t know what to do.

What he most realizes is that he is tired. He has been fighting the heat all day and now it has caught up. But not just today’s, but the fatigue that has been building the last year, especially the last three months, but has been displaced by the urgency of of his search, the strain of dislocation, the surge of doubts, his single, anxious desire to finally settle down, the displacement only making the fatigue deeper, longer when it finally springs, only postponing what he knows is coming.

Portland is a mistake. He won’t be rejected but he won’t fit in. Beneath its friendly surface there is only torpor, into which he will eventually sink.

His blood sugar is up and he has occasional chest pains his doctor said were only nerves though he still advised adjustments.

More can crop up that he sees now, once again.

The real estate agent has not returned.

What is she doing? Casing the joint? Going through his things? Secretly defiling them? None of those suspicions can be possible, but he can’t think of anything likely that might dismiss them, and his mind races for other possibilities without stopping. The dragons’ wide eyes widen further, their open mouths show teeth, their coiling bodies prepare to strike from depths unknown.

He waits until he can wait no longer and starts to head upstairs. At the landing he pauses to look at the Boullée, knowing and thinking about but not voicing what lies inside on the floor, at the center.

“Get lost?” he asks loudly up the well to warn her he is coming, then starts his climb. Ascending the stairs is like descending into a pool, where the greater heat, like the denser water, slows motion and sound.

He stops at the top to catch a breath, then turns right.

Not in the office, the bathroom is silent and vacant.

He looks up the hall and sees and hears nothing, then looks down and sees her shift lying limp and loose on the carpet, pointing like an arrow to the back bedroom, his, and he follows.

Then he sees her lying on his bed.

Then he is beside her, then he sees the tattoo close now, sees that it stops past her shoulder, that the coiling dragons in the design lead to a softer pattern of faint hair, swirling, rising with her breasts, twin basic shapes too subtle for geometry, each subtly different, and descending down the valley of her stomach to a darker pattern.

She cups his neck, pulls him close, and kisses hard while grasping him firmly with her other hand.

And then it isn’t hot.

.

.

He does not feel the post sadness of legend. It is the first time he can remember not feeling complications or having questions return.

“How was—”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” she says. “It was however you want it to be.”

She pauses a moment, thinking.

“Don’t tell my boyfriend.”

And pauses a moment more.

“I’ll tell him.”

He does not give a reply because he doesn’t have one. Instead he lies there, next to her, both on top of the sheets, both fully extended, not quite touching, the sweat not quite cooling, both lightly breathing in the shaded light, both quiet, still, and mortal. Not much else, a bed, a nightstand, a light and clock—he still hasn’t figured out what to do with the room. The lines of the walls and floor and ceiling define a simple box that contains them, their lying bodies. But they reach in diminishing perspective to the grid of Portland streets and extend beyond, forever. Or, instead, the lines converge on them, their breath and sweat. It is as easy to imagine cities rising within these lines as falling.

Below them, downstairs, on a wall, a picture of a dark sphere.

The dragons are Asian, he is sure. They have a stylized complexity in their exotic curves that goes beyond their western counterparts’ singleminded malice. There are meanings. He does not know if the dragons are Japanese or Chinese, however, or the meanings of either, or if the meaning of the dragons before him has moved away from those meanings into some other. The curves, their black outlines, cannot be separated from the curves of her arm, nor can foreground be separated from back, or from her flesh, rather all pulse together almost imperceptibly with her each breath. The dragons coil tightly at her wrist and disappear behind her forearm then return and begin to unwind, unevenly, among a dense pattern of flowers, yellow and orange and blue, and of foliage, the leaves the same green as the scales of the dragons, with shapes of exotic plants he doesn’t know either, the dragons part of the pattern of the plants and the pattern part of them, yet they continue their ascent past her elbow and up her arm and separate themselves, still among the pattern, as much preserving as disengaging, and at her shoulder they do not look at each other but outward and up, fierce intelligence in their eyes and passion in the flames of their bright, red tongues.

The tattoo speaks terror, and hope, and he sees both but does not feel one or the other. Instead he continues to rest next to her, a long time, not knowing how long. Time has stopped, the moment can go on forever. An illusion he knows, but what else do we have. But not an illusion, because he isn’t thinking about either, appearances or time.

.

.

Gary Garvin, recently expelled from California, now lives in Portland, Oregon, where he writes and reflects on a thirty-year career teaching English. His short stories and essays have appeared in TriQuarterly, Web Conjunctions, Fourth Genre, Numéro Cinq, the minnesota review, New Novel Review, Confrontation, The New Review, The Santa Clara Review, The South Carolina Review, The Berkeley Graduate, and The Crescent Review. He is currently at work on a collection of essays and a novel. His architectural models can be found at Under Construction. A catalog of his writing can be found at Fictions.

.

Gary,

Nice work. The piece reads well and displays your distinctive style. I found it full of intrigue and subtlety, working from multiple levels of meaning. And if this was autobiographical, I’m curious who the real estate agent was. Ha.

Bobby