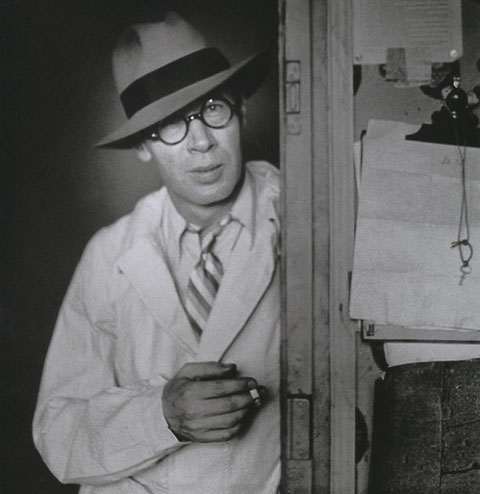

Henry Miller in Paris (photo by Brassaï)

Henry Miller in Paris (photo by Brassaï)

.

Victoria Best has a theory about creativity and writers in crisis. This stunning essay is one of a series of which she writes: “I really loved writing these essays because every writer I chose, once you got down to it, was a hapless flake, making the most terrific mess of their life and yet stalwartly, patiently, relentlessly processing every error, every crisis and turning them all into incredible art. How could you not love these people and their priceless integrity? I felt like I had found my tribe. Didn’t matter in the least that they were pretty much all dead. There was just that precious quality – vital, creative attentiveness to everything wrong – that I cherished.”

By the time 38-year-old Henry Miller left America for Paris in February 1930, he had taken to signing himself as ‘the Failure’. In reality, the ratio of irony to truth in this gesture was uncomfortably low. America had been the scene of repeated humiliation for him; he left behind a bitterly disappointed mother, an ex-wife still pursuing him for unpaid alimony, a dozen poorly paid jobs for which he hadn’t had the stamina or the will, and now the love of his life, June Mansfield.

June had more or less booted him out of the apartment and across the Atlantic. It was a final attempt at forcing him to achieve the artistic genius he so avidly sought; and besides, his prolonged gloom was cramping her style. As he walked away, he was afraid to look up at the window to wave her goodbye, in case she was already engaged in some sort of activity he would rather not know about.

He took with him the sum total of seven years of writing: two manuscripts of dubious merit that no one wanted to publish. When the editor, Bruce Barton, read some of his early work, he returned it with the comment ‘it is quite evident that writing is not your forté’. Miller was taking that remark with him, too, branded on his heart. In his pocket the one useful leaving gift – a $10 note from his friend, Emil Schnellock – wouldn’t last long, but the friendship would prove key to a dramatic upswing in Miller’s fortunes. Not that he had the least premonition of that. As the ship sailed away from the dock, Henry Miller went down to his cabin, thought back over his life and wept.

When he arrived in Paris, the city destined to save him, he sank to a whole new level of poverty. He had nothing, not even a rudimentary grasp of the French language. The days of the famous ‘lost generation’ of compatriot writers were past, luminaries like Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald long gone, leaving Miller, as always, out of synch with his own culture. He had no papers that would help him find work, no family or acquaintances, and no money unless June cabled it to the American Express office, a location he now visited up to three times a day. Mostly, he had to beg, steal or starve. When there was money, he was forced to wonder how she had come by it.

But Paris started to provide him with unexpected resources. He had beauty and degradation all around him, and he had his curiosity, braced by his astute powers of observation. He had the warm and accepting welcome of the French people, and in these hungry times there were café owners willing to extend credit or even feed him for free. In a marked contrast to America, there was compassion for what it was to be a struggling artist. Here, he didn’t have to be making money to call himself a writer. He didn’t even have to be writing something to have his ambition and desire understood. And in this tender absence of pressure, Miller began to settle down to work he didn’t even realise he was doing. He took long walks around his city, absorbing the exotic sights and sounds, and wrote down everything he saw in letters to Emil Schnellock that ran to twenty, thirty pages. It was an eccentric strategy for what would gradually morph into an eccentric, unique, disturbing book.

***

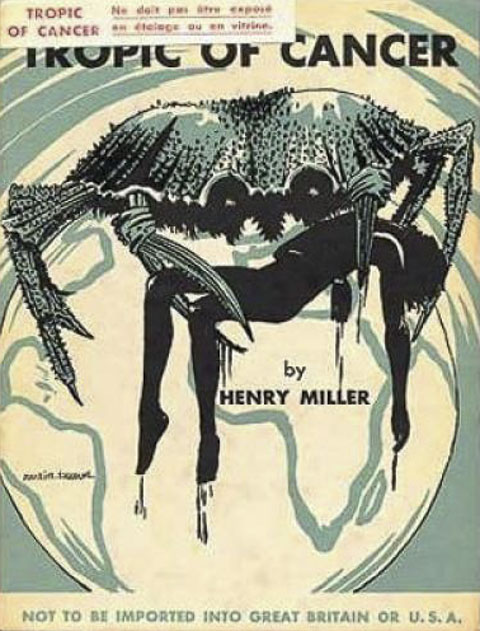

Published in 1934, Tropic of Cancer was the infamous result of Henry Miller’s prolonged struggles, and there would be people who wished he hadn’t bothered. It remains the most grudgingly admired literary bestseller of the twentieth century; a paradigm shifting book that was a sort of Ulysses for the common man. Most of all, it pushed against ingrained puritanism, casually invoking the kind of graphic sexuality that is taken for granted nowadays.

Henry knew he had produced something that was both challenging and insulting. From the moment the book was a finished first draft until its eventual release onto the American market, it was one of his most cherished paranoid fantasies that he would have to go to prison for what he had written. Punishment enough, perhaps, that it was banned beyond the boundaries of France for the next thirty years, and when fame finally arrived, Miller would be too old and too wary to enjoy it.

Cover of original edition, 1934

Cover of original edition, 1934

The crimes of Tropic of Cancer alleged over the next eight decades are various, notably formlessness, and the rash of four-letter words that pit the surface of the otherwise eloquent text like a kind of punctuation. Its characters are unashamedly self-absorbed and hopeless, living the lives of scroungers and scoundrels. But the major assault cited remains on the dignity of sexual relations, reduced to sordid and one-sided tussles between horny men and ‘fuckable cunts’.

That Miller’s narrator utters such insults in a tone of amused indifference rather than hostility or aggression seemed only to rile the feminists further. Kate Millett in the early 1960s decried the image of women in the book as worthless objects, used and abused for the man’s pleasure and too stupid even to know it. Miller, she said, articulated ‘the disgust, the contempt, the hostility, the violence and the sense of filth with which our culture, or more specifically, its masculine sensibility, surrounds sexuality.’ And this criticism of the book has never gone away or been satisfactorily answered. ‘Why do men revel in the degradation of women?’ Jeanette Winterson asked, writing about the book in the New York Times Sunday Review in 2012. Why indeed? But when a man makes unprovoked attacks on the image of womanhood, it’s always worth taking a good look at his mother.

‘It’s as though my mother fed me a poison, and though I was weaned young the poison never left my system,’ Miller wrote in Tropic of Capricorn. Louise Miller was a loveless woman, a strict disciplinarian and a tyrant when crossed or thwarted. She came from a puritanical family with a strong work ethic, but this had not meant security. When she was twelve, her mother had been taken away to the asylum, leaving Louise to bring up her sisters (who would also have breakdowns in time). The authority she wielded was still composed of childish strategies – prolonged rages, violence, a complicated system of irrational rules whose smallest infringement she could not tolerate. Having had to grow up too quickly, she had never grown up at all. She would consult Henry over matters he was far too young to understand. Once she asked him what to do about a wart on her hand and he suggested cutting it off with the kitchen scissors. This she did and subsequently contracted blood poisoning. ‘And you told me to do this?’ she raged at Henry, slapping him repeatedly. He was four years old.

When Henry’s sister, Lauretta, was born, it gradually became apparent that there was something wrong with her. She was a sweet, gentle child but her intelligence never developed beyond that of a nine-year-old. This was something Louise could not accept, and Henry grew to loathe the lessons his mother attempted to give her, which always ended in frustration and lengthy beatings. In his early years, Henry overcompensated for Lauretta, showing off his ability to recite dates and facts and tables to entertain and distract his mother, and defuse her wrath. But the effort soon began to seem greater than the reward; whatever he did it was not enough to save his sister. So Henry rebelled. He acted up in school and fought against all kinds of control and discipline. And at home, he discovered a way of hypnotising himself that helped him escape from the ugly scenes. It would prove useful in other problematic relationships, though it looked from the outside like callousness. In time it would become coldness, hardness, the chip of ice in the heart that Graham Greene said all authors needed to keep their minds free from emotion. Henry Miller would come to provide a perfect example of both a life and an oeuvre in which that icy chip proved vital.

Henry Miller with parents and sister

Henry Miller with parents and sister

Young Henry was attracted to anarchy, but he was sensitive and afraid of fights, qualities he would seek to overcome or hide for the rest of his life. He was growing up in an age that celebrated virile masculinity and sold it as hard as possible, with Teddy Roosevelt as the romanticised poster boy. Henry had a tendency to idolise any man involved in a showily aggressive profession – boxers, soldiers and con men were all high on his list.

Was this because his own father was the embodiment of weakness? Heinrich Miller was a tailor and an alcoholic, of the sodden kind rather than the violent. He avoided home as much as possible, though the rows he had with Louise over the dinner table still gave Henry a nervous reaction that made him gag on his food. Henry was packed off to the Sunday-school sponsored Boys’ Brigade, which promised to drill him in all sorts of soldierly activities. He was delighted with the exercises and the mock battles, but dreaded the moment when members of the group ‘reported for duty’, which involved being taken by the Major into his office and sat on his lap to be fondled. Eventually boys complained and the Major was ousted in disgrace.

This was the crazily gendered world that Henry grew up in, a world in which his mother was the strongest, fiercest and scariest person he knew. It was a world that impressed on men the importance of virility, but the men held up as real role models for Henry were a sad old soak and a paedophile. Being manly was the American imperative and Henry longed to be it, but what did it mean? It couldn’t be about authority or hard graft – that took him too close to his mother. And so gradually the pattern emerged that for Henry, manliness was about freedom from conventional morality. It was about absolute autonomy. It was about surrounding himself with other hapless male souls and accepting their flaws unconditionally.

But what was he to do about his own gentle, sensitive and weak side? The conflict in his personality would prove deeply problematic when it came to sexual relationships. The writer who would be hailed as the Grand Old Man Of Sex fell in love with his first serious passion at sixteen, a pretty young woman called Cora Seward. Every night for four years he would excuse himself after dinner to walk past her house, never pausing to call at the door. That was the extent of his respectful adoration, and also the extent of his fear. Unable to approach his ‘angel’ he went to the whorehouse instead and got himself a dose of the clap. Henry’s attitude to sex was mired in the 19th century, in that torrid hothouse atmosphere of right and wrong, good and bad. When the cool, sweeping winds of 20th-century freedom rushed up to meet it, something tempestuous was bound to result.

***

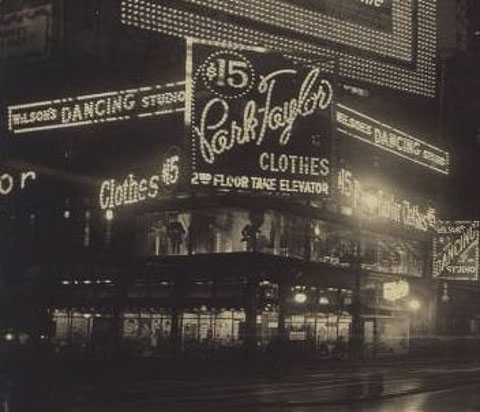

It was late summer in 1923 when Henry walked into Wilson’s dance hall near to Times Square. He was 31. He had come for the taxi-dance, a soft form of prostitution where ten cents could buy a man a dance with the girl of his choice, and his own powers of persuasion would have to do the rest. Miller had a wife and a small child, but the relationship was in the final stages of collapse. ‘From the day we hitched up it was a running battle,’ Henry would later write. He had married because he wanted to avoid conscription but his new wife, Beatrice, brought the battle to the domestic front, nagging Henry to get a job and keep it and do the things a husband should. If there was one thing Henry dealt with badly, it was being told what to do. The man he had become in that marriage was no one to be proud of; he was cruel and insulting to Beatrice, self-centred and reckless. He badly wanted an escape route but his congenital passivity prevented him from finding one.

Wilson’s Dancing Studio, 1920 (photo from New York Public Library online archive via Cosmodemonic Telegraph Company blog)

Wilson’s Dancing Studio, 1920 (photo from New York Public Library online archive via Cosmodemonic Telegraph Company blog)

He noticed a woman walking towards him across the dance hall, a tall woman with a full figure, blue-black hair framing her pale face and brilliant eyes. ‘The whole being was concentrated in the face,’ Henry later wrote. ‘I could have taken just the head and walked home with it; I could have put it beside me at night, on a pillow, and made love to it.’ She was ‘America on foot, winged and sexed.’ She was, in fact, Juliet Edith Smerth from Austria-Hungary, an emotionally unbalanced fantasist, earning what living she could with her body and funding a drug habit. She undoubtedly had tremendous allure, but the gap between what she was and what Henry wrote about her shows the extent of the myth-making, the psychodrama and the sheer power with which he would invest her.

June Mansfield (she made the name up for Henry on the spot) longed to be immortalised in art, and Henry longed for a muse to validate his unproven literary talents. This was what they would ultimately get from each other, although it would cost Henry an acrimonious divorce from Beatrice, and seven years of suffering in this new marriage. ‘She put him through the tortures of hell,’ said Alfred Perlès, one of Henry’s closest friends, ‘but he was masochistic enough to enjoy it.’

From the beginning, June offered Henry the sort of adrenaline- and sex-fuelled excitement he’d thirsted for in his empty life. On their first date in the taxi home, June insisted they were being followed by gangsters, and this set the tone for the drama and the elaborate ruses she loved. She believed in Henry’s ability to write and insisted he stop work to devote himself to art. Henry was keen and June determined, but there was the slight problem of no funds. There followed a long period of odd, short-lived and demeaning jobs, including a speakeasy that eventually foundered. That they were incapable of making money from alcohol during Prohibition says a lot about their business acumen.

What June really liked but Henry didn’t, was what she called ‘golddigging’. This involved June hustling men who were willing to pay cash for any sort of cover scheme that meant they could spend time with her. June often tried to assure Henry that sex was not part of the deal, and Henry did his best to believe this. But biographer Mary Dearborn argued that ‘Jealousy was the glue of their relationship and June made sure to give him ample cause for it. […] She surrounded herself with chaos, and Miller thrived on it. And she kept the relationship, always, at a fevered pitch.’

June Mansfield

June Mansfield

Inevitably things soured. There was so little money, Henry’s writing was going nowhere and ratcheting up tension caused its own problems. One day June brought home a disturbing puppet with violet hair and a black sombrero. He was called Count Bruga and symbolised trouble. Not long afterwards the woman who had made the puppet arrived too. Jean Kronski was a real genius, June said, with clear implications. She had been admitted to Bellevue for observation, but the doctors had agreed to release her if June would stand as guardian; cheering news to hear about an impending houseguest.

Other men might have fled the camp, or refused to play along, but Henry was too emotionally entangled and too passive. So he was forced to become an unwilling witness to his wife’s infatuation with another woman, and June and Jean were able to crank up the madness in their folie à trois. They lived in squalor, washing dishes in the bath, using dirty clothes for towels, the floor strewn with plaster of Paris, paints, books, rubbish. June airily discarded all suggestions she was a lesbian, but Henry had been ousted from her bed and Jean was now in it. Henry made scenes. He made a half-hearted suicide attempt. He took to his bed for ten days (though he was reading Proust). The more uptight he became, the more bohemian and cruel June acted.

There was a protective split opening up in Henry’s character over this time. He was bitterly humiliated by his wife’s behaviour, not least because her relationship with Jean attacked him right where it hurt, in his tentative sexuality. The lack of money and the failure of his ambitions were desperate blows to his self-esteem and he was beginning to loathe America and all it stood for – the work ethic, the commercialism, the disinterest in art. And yet, that chip of ice in his heart was doing its job. When he wrote begging letters to his friends signed ‘the Failure’, he carefully stored the carbon copies, optimistically hoping that posterity would need them. In Nexus, the autobiographical novel he later wrote of this period in his life, ‘Mona’ (June) tells the narrator:

‘You look for trouble. Now don’t be offended. Maybe you need to suffer. Suffering will never kill you, that I can tell you. No matter what happens you’ll come through, always. You’re like a cork. Push you to the bottom and you’ll rise again. Sometimes it frightens me, the depths to which you can sink. I’m not that way. My buoyancy is physical, yours is… I was going to say spiritual but that isn’t quite it. It’s animalistic.’

He may have been lost in emotional chaos, but Henry was following his lodestar. ‘It knows that all the errors, all the detours, all the failures and frustrations will be turned to account,’ Miller wrote in Nexus. ‘[T]o be born a writer one must learn to like privation, suffering, humiliation. Above all, one must learn to live apart.’ He got to do just that when he returned home one day and found a note on the kitchen table, telling him that June and Jean had sailed for France. Not only had Jean usurped his place in June’s heart, she’d hijacked his cherished dream of escape, too. June would return in a couple of months without her and determined Henry should see Paris, but he could not foresee this. Instead, he broke every piece of furniture in the apartment and alarmed the landlady with his howling. When the initial despair passed, Henry realised that this was something he could write about; in Nexus he describes sitting down and taking notes. He had been following his instincts, but now illumination came to him: the brutality, the humiliation, the intense misery and the deprivation were a story, the best one that had ever been given to him. It would take him many years to put that story into words, but the revelation was important. From now on, Henry knew that his own life would become his art.

***

The transformation that Paris effected on Henry’s writing style was little short of miraculous. In America he’d been trying to shoehorn his anarchic outlook into the sort of 19th-century fictional models favoured by his literary heroes, Knut Hamsun, Theodore Dreiser and Dostoyevsky, and the contrast was awkward and false. Just as his passive personality did not fit the go-getting attitude popular in America, neither did his coarse and chaotic style. ‘There was a retirement about the idea of literature, a sort of salon atmosphere, which Miller feared would never be able to accommodate a rude voice like his,’ writes biographer, Robert Ferguson. Once he left it all behind, Henry realised how suffocated he had been.

In Paris, he was able to give in to his instincts, which Ferguson describes as ‘those of a film producer whose consciousness was actually a machine for assembling a cast, picking the locations and taking notes for the script of a major production.’ Eye-catching Paris offered him visual riches; grubby, valiant, warm-hearted Paris, full of losers and eccentrics, where there was even a place for a prostitute with a wooden leg, as Miller would memorably describe. The literature of France had already embraced the poor, sordid aspects of existence: Zola had described his whores with intense pity, and now Henry could come along and write about them with an ex-pat’s pride, as the kind of landmark that would be extraordinary back home, but which he now took in his stride.

Paris cafe, 1930s

Paris cafe, 1930s

Freed from the mesmerising chaos of June, Henry woke up; he looked and listened carefully. ‘Hearing another language daily sharpens your own language for you, makes you aware of shades and nuances you never expected,’ he would later tell an interviewer for the Paris Review. He had fallen by chance into exactly the right practice exercises. Writing to Emil Schnellock he enthused that ‘In a letter I can breeze along and not bother to be too careful about grammar, etc. I can say Jesus when I like and string the adjective out by the yard.’ His new friend, Michael Fraenkel, read one of the manuscripts he’d brought with him from America and advised him to tear it up. He told Miller to write as he spoke and as he lived.

Henry then found a way to convey the hallucinatory vividness of the life he was living. He had gone to the movies and seen the avant-garde film of the moment, Un Chien Andalou by Luis Bunuel and Salvadore Dali. The film made ‘a lasting impression on him’, according to Frederick Turner, author of a study on the genesis of Tropic of Cancer: ‘he was intrigued by its formlessness, its sudden, jolting scenes of cruelty, which felt as if the artists were mysteriously inflicting these on audiences conditioned to regard movies as a passive form of entertainment.’ Paris was high on crazy artworks where there were no limits, where cruelty was all the rage, and suddenly, Henry fit right in; he loved forcing readers to accept unpalatable truths. He began to conceive of a new kind of book, one based on his experiences in France, and he wrote excitedly to Schnellock ‘I start tomorrow on the Paris book: First person, uncensored, formless – fuck everything!’

Paris even helped him find the right mindset to deal with the failures of the past and the uncertainties of the future. It was here that he discovered the Tao Te Ching, whose philosophy of going with the flow and accepting all the confusion and sorrow as essential aspects of existence offered him exactly the even-tempered fatalism that chimed with his heart. That chip of ice was beginning to look like wisdom. For the first time he was given permission not to wallow in failure but to look at it squarely as necessary, unavoidable, and beyond the reach of judgement. When he came to write about it in Tropic of Cancer, he would take it a twist further, producing a book that was a tenderly satirical celebration of the very worst in humanity.

There was of course one more thing Henry would need to write his book, and that was money. One of his survival tactics in the early days was to exchange a bed for the night for housekeeping services, and this he did with Richard Osborn, an American lawyer working for the National City Bank by day and fancying himself a bohemian writer at night. Osborn introduced Henry to his boss’s wife, Anaïs Nin, and the two quickly became infatuated with each other’s minds, bonding over a shared interest in D. H. Lawrence.

Miller knew he was punching above his social weight. Anaïs was properly exotic and genuinely cultured, having been born in Paris and lived in New York and Cuba. She also wanted to write and had a dominantly erotic nature, one fuelled by desire and curiosity and not, like June’s, in order to pay the rent. Instead, she started giving Henry books, then paying his train tickets and slipping him 100 francs in an envelope. June, visiting Henry in Paris, wanted to see this magical mentor, and there was an instant attraction between these two women who both liked to play the alpha female. Anaïs was alert to all that was alluringly perverse in June’s nature, and once again Henry found himself shunted to one side while two women circled each other in fascination.

Anaïs Nin

Anaïs Nin

This time, though, June could not be tempted into a relationship with Nin. ‘Anaïs was just bored with her life, so she took us up,’ she would later claim, and Nin would call it ‘the only ugly thing I have ever heard her say.’ June became, instead, a catalyst between Anaïs and Henry, as they endlessly discussed her and dissected her mystique. The balance of the relationship with June was changing, though, for Henry was falling hard for Nin. He blamed this latest humiliation on June, whilst Anaïs, who had in fact attempted all the seducing, could do no wrong.

Henry wrote breathlessly to Schnellock, ‘Can’t you picture what it is to me to love a woman who is my equal in every way, who nourishes me and sustains me? If we ever tie up there will be a comet let loose in the world.’ This time June fought and made the scenes to no avail. She returned, defeated, to America in a split that would be definitive, and Henry and Anaïs became lovers. Passion was the last alchemical element Henry needed, and once with Nin he found he was writing swiftly and well, producing a bold, innovative, painfully honest, surprisingly funny book.

Miller took all that he’d been through in Paris and transformed it into something coherent and artistically shapely. Later in life he would call himself the ‘most sincere liar’, which is a fine description of any fiction writer. He took the people he’d been living with and gave them fictional names whilst enhancing the worst parts of their personalities; he took the real places that he’d been and described them through the vocabulary of decay and disease. But most of all he used that chip of ice to take an emotional step backwards and infuse his narrator’s voice with tender and amused acceptance of everything he saw. This happy absence of judgement upon a life of squalor lived without dignity made the novel endearing to readers who had suffered intolerable humiliations of their own. Tropic of Cancer offers a powerful affirmation of the strength of the human spirit, even in the most depressing and hopeless of conditions.

But this was in some ways incidental to Henry’s preoccupation with writing an entirely new kind of manliness, which involved surrounding himself with hapless males and regarding their faults with indulgence. ‘I just want to be read by the ordinary guys and liked by them,’ Miller wrote to Schnellock. One of the flaws he portrays honestly and indulgently in his ordinary guys is the way they have sex on the brain but lack the emotional intelligence, the class and the courage to have anything like a real relationship. Take for example his friend, Carl, pondering the ethics of becoming involved with a rich older woman he’s not attracted to:

‘But supposing you married her and then you couldn’t get a hard on any more – that happens sometimes – what would you do then? You’d be at her mercy. You’d have to eat out of her hand like a little poodle dog. You’d like that, would you? Or maybe you don’t think of those things? I think of everything.… No the best thing would be to marry her and then get a disease right away. Only not syphilis. Cholera, let’s say, or yellow fever. So that if a miracle did happen and your life was spared you’d be a cripple for the rest of your days. Then you wouldn’t have to worry about fucking her any more… She’d probably buy you a fine wheelchair with rubber tires and all sorts of levers and whatnot.’

Or the dastardly Van Norden, a man who defiles everything he touches, terrified at being so continually abandoned in the trenches of the erotic:

‘For a few seconds afterwards I have a fine spiritual glow… and maybe it would continue that way indefinitely – how can you tell? – if it weren’t for the fact that there’s a woman beside you and then the douche bag and the water running… and all those little details that make you desperately selfconscious, desperately lonely. And for that one moment of freedom you have to listen to all that love crap… it drives me nuts sometimes…’

Erica Jong, writing in fierce defence of the book, argues that Tropic of Cancer works with the same principles as feminist literature, ‘the same need to destroy romantic illusions and see the violence at the heart of heterosexual love.’ And it’s true that the characters in the book are rigorously stripped of pretension and the dishonest flourishes of ego, vanity and pride. The point of plumbing the depths of the human condition is at least in part to clear away all illusion and delusion, for Miller believed that idealism had damaged the world far more than any acceptance of our base physicality might, and that this idealism affected far more than mere sexuality.

In one of the defining anecdotes of Tropic of Cancer, the narrator escorts a young and inexperienced Hindu man to the local brothel. In nervous confusion he uses the bidet as a toilet, horrifying the Madame and her girls and embarrassing himself. But the narrator, unfazed as ever, sees universal significance in the incident of an uncommon kind. The basic problem of life, he says, is that ‘Everything is endured – disgrace, humiliation, poverty, war, crime, ennui – in the belief that overnight something will occur, a miracle, which will render life tolerable’. Such a belief flies in the face of reality and demands an arresting rebuttal.

‘I think what a miracle it would be if this miracle which man attends eternally should turn out to be nothing more than these two enormous turds which the faithful disciple dropped in the bidet. What if at the last moment, when the banquet table is set and the cymbals clash, there should appear suddenly and wholly without warning, a silver platter on which even the blind could see that there is nothing more, and nothing less, than two enormous lumps of shit.’

The very structure of the joke – the enormous disparity between transcendental miracles and shit – gives away the subtle, underlying structure of the book. It’s the gap between the outspoken dreadfulness of Millers’ characters and our desire to identify with noble, sympathetic figures that is at once so awful and so funny, just as the expletives jar the beauty of the language, and the insulting attitude the male characters assume towards women is a lame stab at covering up their obsessive need for them, a need which rings out in the narrator’s lament for the woman he adored and who has returned to America without him:

‘I couldn’t allow myself to think about her very long; if I had I would have jumped off the bridge. […] When I realize that she is gone, perhaps gone forever, a great void opens up and I feel I am falling, falling, falling into deep, black space. And this is worse than tears, deeper than regret or pain or sorrow; it is the abyss into which Satan was plunged. There is no climbing back, no ray of light, no sound of human voice or human touch of hand.’

It was this familiar existential crisis – the pain of the mismatch between human aspirations and desires and the wholly insufficient reality that has to be accepted in their place – that finally formed the mainspring of Miller’s creativity.

The literary insight of the novel didn’t stop Tropic of Cancer being smuggled out of France by tourists for the next thirty years as the ultimate dirty book; sex sells but it also blinds. The book’s reputation rode far in advance of any reading that took place, and its tendency to stir strong emotions and ridicule with keen precision the most sensitive issues precluded much in the way of critical appraisal. It was a book that readers loved or hated, with their guts.

Nowadays the history of its suppression and the crude portrayal of women win all the headlines, but the real story of the book concerns the dominance of the women who provoked and created it: Henry’s fearsome mother, his sweet, crazy sister, his troublesome muse, June, and the book’s midwife, Anaïs Nin, who put up the money needed for publication. The book is an act of self-assertion that couldn’t help but reveal both the depths of his dependency on women, and the force of his resistance.

x

Notes on Sources

I am indebted in this essay to three masterly accounts of Miller’s life: Mary Dearborn’s The Happiest Man Alive (HarperCollins, 1991), Robert Ferguson’s Henry Miller: A Life (Hutchinson, 1991) and Frederick Turner’s brilliant and detailed account of Miller’s creativity, Renegade: Henry Miller and the Making of Tropic of Cancer (Yale University Press, 2012). Also unmissable on Henry Miller’s life is Henry Miller. Tropic of Capricorn (1939), Nexus (1960) and Sexus (1949) all contributed to my understanding and remain extraordinary writings on the borderline of fiction and autobiography. Finally, Kate Millett’s essay on Miller in Sexual Politics (Virago, 1977) and Erica Jong’s The Devil at Large (Vintage, 1994) are, respectively, a fine critique and a fine tribute from the other side of the gender divide.

—Victoria Best

x

x

Victoria Best taught at St John’s College, Cambridge for 13 years. Her books include: Critical Subjectivities; Identity and Narrative in the work of Colette and Marguerite Duras (2000), An Introduction to Twentieth Century French Literature (2002) and, with Martin Crowley, The New Pornographies; Explicit Sex in Recent French Fiction and Film (2007). A freelance writer since 2012, she has published essays in Cerise Press and Open Letters Monthly and is currently writing a book on crisis and creativity. She is also co-editor of the quarterly review magazine Shiny New Books. http://shinynewbooks.co.uk

x

x

Enjoyed this essay, a distillation of the cross currents of that time into the flow of this one. Reminded me of Joyce Johnson’s “Minor Characters,” another insightful look at the sexual confusions and delays in a driven but misplaced pursuit of emotional wholeness that produces resonant art and reminds us of psyche’s inevitable drive to reunite with Eros. Interesting point of view on this from Miller’s old age essays, especially the one called “Mother.”

Thanks to Victoria Best for taking a high road in this inclusive and well-written overview of sources behind and reactions to Tropic of Cancer, and for her insights and ecumenical tastes.

“Well I was going to say I saw a ducky and a horsey, but I changed my mind” Charley Brown. I´m not capable of travelling an intellectual high-road, but I find your essay, Victoria, very astute and well-researched. Having spent time at Henry´s house as a child and only having positive memories of him, I find your stance and exposition very close to truths that those in Henry´s wake have been searching for for years.