.

The Great War

…….–International Writers Conference Excursion

A moment ago we passed the Italian charnel house,

we writers from a handful of nations,

who this morning passed a declaration for peace.

Of course. Who’d be against it?

Some, it would seem. We keep on going

as fast as we can on roads that twist through high passes.

One Turk is a skeptic:

he notes how some tribes pray that rain will fall

as we do that peace will.

If either one comes… His voice flickers out;

he ends with a shrug.

A century gone, and more, the Great War.

And I’m just an American,

struck more by beauty than history.

I recognize as much in myself, ashamed.

We see photos of faces,

or what had been faces, in the museum

at Kobirad, or Caporetto.

Shards of headstones hang on a wall:

caduto in guerra, some of them tell us,

and I know that language: fallen in war.

I can’t read the Slovene inscriptions.

Marble is marmore in Italian,

which I use with my seat-mate Giulio.

I don’t know a Slavic word for the stone–

for much at all.

Hemingway’s portrait shows on another wall.

There’s Goran, a Serb. Zvonko’s a Croat,

both from Sarajevo.

They’re friends, and solemn. My own dear friend Marjan,

the Slovene who translates my poems,

knows better than I

what those two men have been through.

He says, “I’m honored to count you as friends.”

Back on the bus we’re all full

of high spirits and laughter.

We imagine we’re one big family.

Through the window, arcing in wind,

I see airplanes and hawks

high over the valley, which is gorgeous and green.

There are bears and wolves in these mountains,

the Julian Alps that enclose us.

Artillery blared here for months,

although as many died from cold as gunfire.

The Soca River below us holds a monster fish

called salmo marmoratus,

which can grow to forty pounds and more.

To catch one would make for a lengthy battle.

Marjan buys me a favorite local fly

for the marble salmon.

Later I’ll see it, he says, and want to return.

Soon we’ll all break bread.

Soon we’ll toast each other–

here in the landscape of A Farewell to Arms.

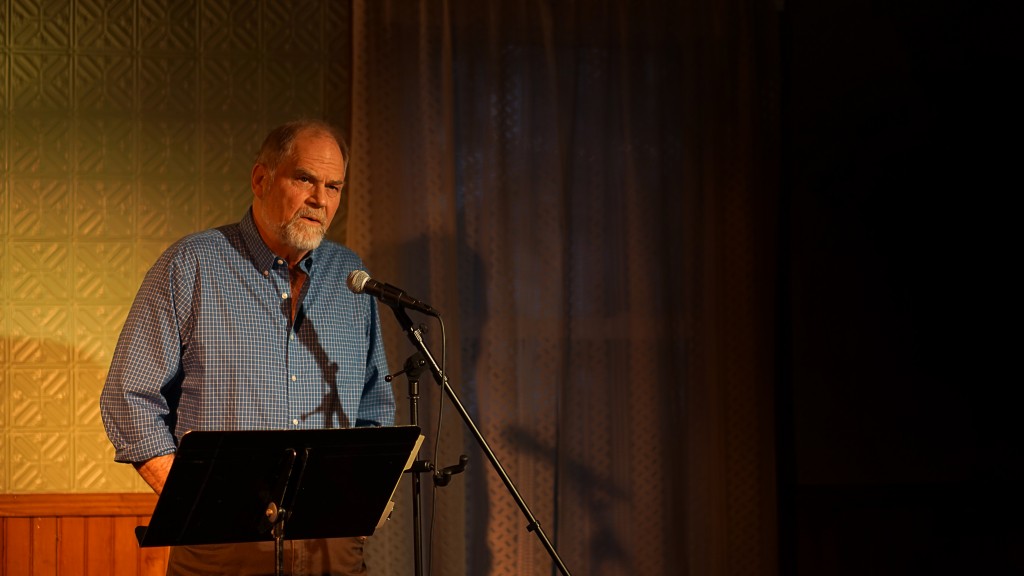

—Sydney Lea

.

Sydney Lea is the former Poet Laureate of Vermont (2011-2015). He founded New England Review in 1977 and edited it till 1989. His poetry collection Pursuit of a Wound (University of Illinois Press, 2000) was one of three finalists for the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. Another collection, To the Bone: New and Selected Poems, was co-winner of the 1998 Poets’ Prize. In 1989, Lea also published the novel A Place in Mind with Scribner. Lea has received fellowships from the Rockefeller, Fulbright and Guggenheim Foundations, and has taught at Dartmouth, Yale, Wesleyan, Vermont College of Fine Arts and Middlebury College, as well as at Franklin College in Switzerland and the National Hungarian University in Budapest. His stories, poems, essays and criticism have appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New Republic, The New York Times, Sports Illustrated and many other periodicals, as well as in more than forty anthologies. His selection of literary essays, A Hundred Himalayas, was published by the University of Michigan Press in 2012, and Skyhorse Publications released A North Country Life: Tales of Woodsmen, Waters and Wildlife in 2013. His twelfth poetry collection, No Doubt the Nameless, was published this spring by Four Way Books.

.

.

Lovely poem Sydney. Very evocative and clear. We all wish to be pure of heart, and so we see the past in sadness and sorrow as we seem to repeat ourselves at our worst, and in some cases at our best. The goodness of America shines through here at a time when so much of the noise coming into the world from that nation is so awful and full of the mendacity and ugliness of war talk. I even heard the words nuclear exchange uttered by a former Obama advisor yesterday as though that madness were possible. Let us stay true to the spirit expressed in your fine poem. Peace & Love. We had a moment’s silence here in Port Dover on July 8th, and a prayer for Peace and Love followed by poems in the name of sanity. In the words of the great Spanish poet Miguel Unamuno “Viva la vida” … John B.