.

Umberto Saba is an Italian novelist who wrote this classic novel of gay adolescence in the 1950s when he himself was in his seventies. It’s just been published by New York Review Books in a translation by Estelle Gilson, and we are excited to be able to offer this tantalizing excerpt. In this scene the boy Ernesto takes the first step toward the sexual relationship with an older fellow worker.

§

The man put his hand on the boy’s, which lay palm down on the sack. He looked nervous. “It’s really too bad,” he said, surprised and pleased that the boy hadn’t withdrawn his own.

“What’s too bad?”

“What I said before. That we can’t be friends, and go walking together.”

“Because of the difference in our ages?”

“Not that.”

“Because you’re not dressed well enough? I already told you, things like that don’t make a bit of difference to me. So. . . .”

The man was silent for a long time. He seemed to be uncertain of himself, as though he wanted to say something and yet not say it. Ernesto felt the hand resting on his own trembling. Then the man stared directly into the boy’s eyes, and as though taking a desperate risk, suddenly blurted in a strange voice, “Do you know what it means for a boy like you to be friends with a man like me? Because if you don’t know yet, I’m not going to be the one to tell you.” He was silent again for a moment. Then realizing that the boy was blushing and had lowered his head, but had not withdrawn his hand, he added almost belligerently, “Do you know?”

Ernesto withdrew his now damp and sweaty hand from the grasp, which had become tighter, and placed it timidly on the man’s leg. He moved it slowly up his leg until, as though by accident, it brushed lightly against his genitals. Then he raised his head, and smiling brilliantly, stared boldly into the man’s face.

The man was consternated. His saliva dried in his mouth, his heart beat so quickly that he felt sick. All he could manage to say was “You understood?” which seemed more addressed to himself than to the boy.

There was a long silence that Ernesto was the first to break. “I understood,” he said, “but where?”

“What do you mean, where?” the man answered as though in a fog. Ernesto appeared more at ease than he.

“To do that stuff that you shouldn’t be doing, don’t we have to be alone?” he asked.

“Yeah,” the man replied.

“So where do you want us to be alone?” whispered Ernesto, though his daring had begun to fade.

“Tonight, out in the country. I know a place.”

“I can’t,” said the boy.

“Why, you go to bed early?”

“I wish! I’m practically asleep on my feet by the time I get home, but I’ve got to go to night school.”

“You can’t skip once?”

“I can’t, my mother walks me there.”

“She’s afraid you won’t go?”

“Not that. She knows I don’t lie to her. It’s an excuse for her to get out and get some exercise. She wants me to take stenography and German. She’s always saying you can’t go far in the world if you don’t know German. Anyway, I’d be a little scared to be out in the country.”

“Scared of me?”

“No, not you.”

“Then what? My clothes? If you’d be ashamed I could wear my Sunday stuff.”

“Someone could come by and see us.”

“No way in the place I know.”

“Well, I’d be scared anyway. Why not here in the warehouse?”

“There’s always people around. It won’t work,” he said (though he knew that Ernesto had keys to the warehouse). “If the two of us came out of here together after closing, it would look real suspicious. Worse, the boss lives right across the street. And you know that wife of his is worse than him. She’s always looking out the window.”

“Can’t we fake an excuse? Make believe we forgot something? When I’ve got a lot of work to do, I come back in at two, right after lunch. I don’t wait for the boss to come in at three. That’s why he gave me the key. Sometimes I’m alone for more than an hour. And you can always say— Hey, here comes the cart!”

First the heads, then the bodies of two sturdy draft horses appeared in the open doorway. The cart followed, then the carter standing up with the reins and whip in his hands. But even before the horses obeyed his order to stop, a large, heavy man who was to help with the unloading leaped down from the sacks upon which he had been seated cross-legged like a Turk and called out drunkenly to Ernesto’s friend.

“We’ll talk later,” the man said hurriedly and gruffly. Replacing the kerchief he had removed from his head while talking to Ernesto, he headed toward the exhausting task awaiting him. His legs trembled slightly as he walked.

§

After the two men had unloaded the sacks (not without the fat man’s curses and insults), and after Ernesto had completed the work of listing and marking every one of them, Cesco (the fat one), who with all his beggary and bitching must have drunk more than usual that day, started a furious argument with the boss. Ernesto’s friend, however, wasn’t in the mood to argue with anyone. There was only one thing he wanted to do: get to a fry house, gulp down everything they put on his plate, then go home, get into bed, and think. What had happened, or, rather, what was going to happen with Ernesto, was something he’d been dreaming of for months (from the first moment he’d seen him) and he was (if one can ever make such a claim) happy. But his happiness was not untinged by fear—that the boy might have regrets beforehand, feel insulted afterward, or be dumb enough to go around talking about it. But he always accepted whatever payment the boss offered without batting an eye when Ernesto had come looking for him in the piazza. In fact, to his mind, that little bit of money had become much more, because it was Ernesto who was relaying (not setting) the amount. But the fat man didn’t have any such reason not to gripe about money. Moreover he was drunk. The boss, a Hungarian Jew—much enamored of Germany, where he said he had studied and lived for a number of years—was defending himself in dreadful Italian, which gave away his foreign birth. It was an Italian that didn’t merely offend Ernesto, who in addition to being a Socialist was staunchly pro-Italian; it downright pained him. As a child he had read biographies of Garibaldi and of Victor Emmanuel II, the only books in his home, forgotten there by his uncle. What irritated Ernesto most was the word “Germany,” which the boss mispronounced as “Chermany” and which he used frequently (in fact, as often as possible) in order to praise the (unique) virtues of its people. However, Cesco’s violent threats, which the man, as co-worker, was obligated to support, finally prevailed over the boss’s miserliness, which I can’t say had violated any law (there were no laws in those days to protect workers, much less day laborers), although it did violate the accepted practices of the piazza. Grudgingly, he agreed to an increase. That day and from then on, instead of being paid three florins, the two men would be paid four florins to be divided equally between them. It was the amount Ernesto’s friend had wanted, and he immediately turned to leave when the boss called him back to tell him that he needed him to work the next day. He hired him for the entire afternoon. In fact, because it wasn’t possible to deliver the sacks to their destination before three o’clock and many were leaking and required repair, he told him to come in an hour before opening time. He would pay him, he added (though through clenched teeth), for the extra time. Then the very distrustful Signor Wilder, who never assigned a laborer to work in the warehouse without Ernesto’s supervision, turned to the boy to tell him that he too would have to be at work earlier the following day. It was fate speaking (in Signor Wilder’s voice) in a way that was as unexpected as it was peremptory. The man and boy turned away immediately, not daring to look at each other. But something flashed in the man’s eyes and one could see him swallow softly. He left quickly, barely saying goodbye. The boy turned back to his correspondence. But his thoughts too were elsewhere.

— Umberto Saba, translated from the Italian by Estelle Gilson

“Copyright © 1975, 1978, 1995, 2015 by Giulio Einauldi editore s.p.a., Turin; Translation copyright @ 2017 by Estelle Gilson”

.

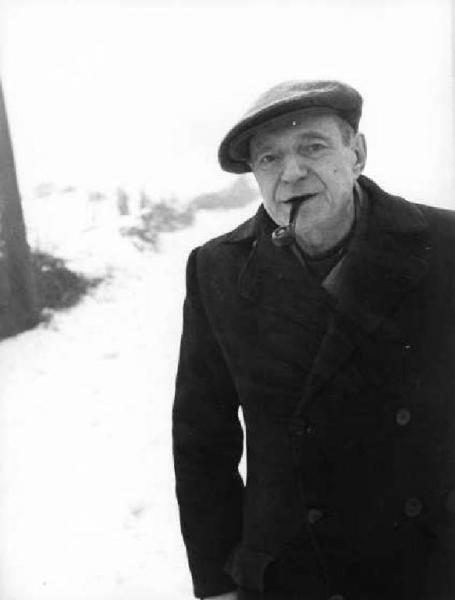

Umberto Saba (1883–1957) was born Umberto Poli in the city of Trieste, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and continued to live in Trieste for the greater part of his life. The child of a broken family—his father, who had converted to Judaism to marry, soon abandoned his wife—Saba attended the Imperial Academy of Commerce and Navigation in Trieste, and then moved for some years to Pisa, where he studied classical languages and archaeology. In 1909 he married Carolina Wölfler, also Jewish, and the subsequent year she gave birth to a daughter; a first book of poems, published under the name of Umberto Saba, also appeared that year. Saba’s marriage was at first troubled—his wife’s affair with a painter led to a brief separation—and the couple was poor, and for a few years they moved around Italy in the hopes of improving their fortunes. After the end of World War I, however, Saba bought a secondhand bookshop in Trieste—he called it La Libreria Antica e Moderna—and in the next decades he made a comfortable living as a bookdealer while working on Il Canzoniere, the book of poems he published in 1921 and would go on adding to for the rest of his life. During World War II, Saba and his family were forced to flee Trieste and go into hiding in Florence to avoid deportation by the Nazis. Though the postwar years brought him many prizes and widespread recognition as one of modern Italy’s greatest poets, Saba suffered from depression, which had plagued him all his life, and opium addiction and was repeatedly institutionalized. He died at seventy-four, within a year of his wife.

§

Estelle Gilson is a writer, translator, and poet. Among her translations are works by Stendhal, Gabriel Preil, Natalia Ginzburg, Massimo Bontempelli, and Giacomo Debenedetti. Her translation of Stories and Recollections of Umberto Saba was awarded the MLA’s first Scaglione Prize for the best literary translation of the previous two years.

.

.