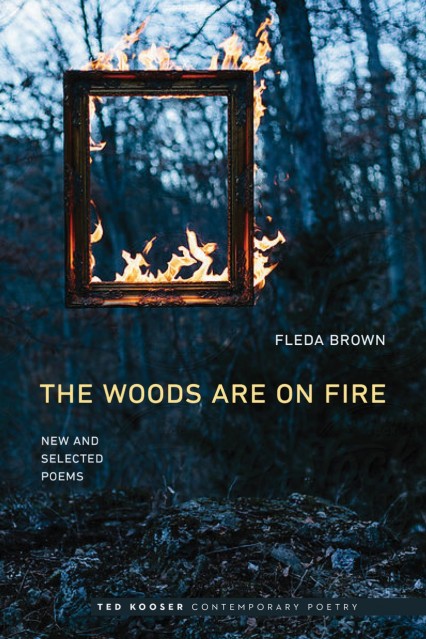

The Woods Are On Fire: New and Selected Poems

Fleda Brown

University of Nebraska Press

275 pages, Paperback $19.95 US

978-0-8032-9494-3

Former Poet Laureate and editor Ted Kooser, in his introduction to Fleda Brown’s recently published The Woods Are On Fire: New and Selected Poems, says this about the book: “You hold the first of these poems in your left hand and the last in your right, and in between is the carefully and beautifully presented record of the life of a talented and influential American poet. And a person who reaches, in welcome, to you.”

Exactly right. At every turn in this book – made up of poems from six previous books along with fifty new poems – the poet Fleda Brown opens the door to her life and invites you in.

I teach my niece Elizabeth

to let down her oars,

then pull and lift with mine.

Our wake smooths

like a tail. Elizabeth says

we are a dragonfly,

double-oared. I think

we are an old woman,

our low whaler spreading

the reeds with wide hips,

sloshing hollow…..

from “Whaler”

Key to the enjoyment of Brown’s welcoming invitation is a taste for complications – not the complications of language, and not the complications of form or structure, but the complications of life. Brown’s life, filtered through language which avoids sentimentality and obfuscation, is reflected in poems, which examine burdens, confusions, illnesses, losses, reservations and constraints. But it’s also reflected, sometimes as counterpoints within the same poems, in moments of determination, reflection, wonder, hope and heart, as with one of my favorite poems in the book (taken from Reunion, published in 2007) which describes something called “the perfection knot”:

Knot Tying Lessons

The Perfection Knot

—a favorite loop among anglers, it has survived

the advent of slippery nylon monofil, which has

rendered many other knots obsolete.

How do we keep from going mad,

starting over with marriages and children,

making the same mistakes?

Over and over, we leave behind

the buoys that marked the shallows

we should have seen. They bob like zeros

behind us, counting for or against, who

can be sure? Maybe everything was

simpler than we thought from the start,

perfect as the disk of the sun, and the first

loop we took was never supposed to be

tied in some frivolous bow. Maybe

we were to come through the loop bravely,

cross its outer border until we could see

clearly how it was we began all this,

slip under what we used to think

was the route, until we caught

our waywardness in a noose, and nothing

could slip loose. Maybe it’s the kind of thing

you have to teach your hands to do

without puzzling too much about it,

the way you faithfully get up, go to work,

come home. Like the rotation of the planets,

you have to believe than just because

no one says so, doesn’t mean you aren’t

okay, more than okay, really,

in your devotion to what you can’t

exactly explain.

The Woods Are on Fire is a hefty volume – 275 pages – published by the University of Nebraska Press as part of its Ted Kooser Contemporary Poetry series. Previous volumes in the series include Darkened Rooms of Summer by Jared Carter (2014), and Rival Gardens by Connie Wanek (2016.) All three books – Brown’s, Carter’s and Wanek’s – offer “new and selected” work; decades of thought-provoking writing are represented, and Kooser has chosen his poets well.

Brown, who taught for many years at the University of Delaware and was Delaware’s Poet Laureate from 2001 to 2007, maintains an interesting blog called “My Wobbly Bicycle.” One of her recent posts includes this poem, another favorite of mine included as an excerpt from the book Reunion:

Mouse

I admire the way mouse dashes across the top bracket

of the blinds while we’re reading in bed. I admire the tiny whip

of its tail at the exact second my husband tries to grab it.

I admire the way it disappears into our house and shreds various

elements. I admire the way it selects the secret corridors

behind cupboards and drawers, the way it remains on the reverse

side of our lives. The mouse is what I think of when I think of

a poem, or of music, going straight for the goods, around

the barrier of our thoughts. It leaves droppings, pretending to be

not entirely substantial, falling apart a little here and there.

Clearly, it has evolved perfect attention to detail. I wish it would

concentrate on the morning news, pass the dreadfulness out

in little pellets. Yesterday I found a nest of toilet paper and

thought I’d like to climb onto that frayed little cloud. I would like

to become the disciple of that mouse and sing “Wooly Bully”

in a tiny little voice in the middle of the night while the dangerous

political machines are all asleep. I would like to have a tail

for an antenna. But, I thought, also, how it must be to live alone

among the canyons of cabinets, to pay that price, to look foolish

and trembling in daylight. Who would willingly choose to be

the small persistent difficulty? So I put out a spoonful of peanut butter

for the mouse, and the morning felt more decent, the government

more fair. I put on my jeans and black shirt, trying not to make

mistakes yet, because it seemed like a miracle that anyone tries at all.

In this poem, Brown moves from admiration to envy to pity and, finally, to empathy. Her reactions to the simplest things – a chicken bone, a small flower, a bus stop, mushrooms – often clearly demonstrate the changing perspectives of a poet trying to figure things out, trying “not to make mistakes” but, in the end, accepting the fact that much about this world will remain a mystery.

Brown herself, in an interview in which she was asked to describe her poetry, said this: “I am strongly convinced that poetry should be accessible on the rational level as well as pointing our way into the irrational, non-linear place we often call the dream world.” Lines like the following about a woman and her lover from “Love, for Instance”(from Fishing with Blood) illustrate Brown’s point: “And look at her eyes as she kisses him, / wide open, deliberate as his flowers. She watches him / roll out of her mouth like a ghostly language….”

The Woods Are on Fire contains excerpts from all but one of Brown’s previous books; the exception is titled The Devil’s Child, a long and continuous narrative poem, and Brown states in her acknowledgements that “the tone of the book made it impossible to fit among these other poems.” Nevertheless, she considers it her best work, one to be looked up and read separately.

One book from which poems are taken is The Women Who Loved Elvis All Their Lives. All the excerpts deal with Elvis in one way or another – memories of what an adolescent’s life was like in the 50’s, and specific events in Elvis’s life: how he shook hands with Nixon, how he went into the army, how he sang gospel songs. What might have turned glib or silly in another poet’s hands remain meditative in Brown’s. As Elvis talks with Nixon, the singer “… tries to get across that he knows the awful changes / the country can make when you’re not looking, / how one moment can desert the other / and leave you standing in the footlights, / trying to remember if you’re supposed to shoot or fly.” An earlier poem from Fishing with Blood describes the fan-rivalry between singer Ricky Nelson and Elvis this way: “Ricky and Elvis conflicted down our bulletin boards, / a plain philosophical choice: country-club white / or the deep rumble from the edge of black.”

The most heart-wrenching of the poems in the book are about illnesses and disabilities in her family – the condition of her mentally retarded brother, the vulnerabilities of her aging mother and father, the illness of a well-loved sister. The Woods Are on Fire is a collection meant to be read from cover to cover, unlike some books of poetry which feel best if read by dipping in at any page to read a solo poem. Instead, with Brown, we turn the pages and watch her own sensibilities deepening, we note a perspective developing over the years. Once read, this book will be read again, and we’ll pull the book from the shelf often as a poetic reference text, so to speak, for moments in our own lives which correspond. This is the kind of light-filled book we use to see the world more clearly and make our way forward – and we do it with a poem in each hand, as Kooser recommends.

—Julie Larios

.

Julie Larios is a Contributing Editor at Numéro Cinq. She is a poet and lives in Seattle.

.

.

Dear Julie: Fleda is an absolute gem, and only a person as smart and insightful as she could write so accurate and moving a review. Nothing could be terser nor on-the-money, say, than this: “Brown’s welcoming invitation is a taste for complications – not the complications of language, and not the complications of form or structure, but the complications of life. Brown’s life, filtered through language which avoids sentimentality and obfuscation, is reflected in poems, which examine burdens, confusions, illnesses, losses, reservations and constraints.” Home runs, both of you!

Thanks, Sydney. I realized, while writng the review that I could learn a lot about both writing and life from this fine poet, especially from her ability to be both generous and unsentimental. My notes in the margins fill the book – “Try this” was one constant nudge to myself as a poet. You’re right: she’s a gem.

Thank you Julie Larios for this wonderful, thoughtful, and beautifully written review. It’s what we all hope for.

A small addendum here: I love what Fleda Brown wrote once about technique and form: “Technique it seems to me comes from hearing. Hearing the sounds we make on the page. Knowing what we want them to do and WHY. It seems useful and, indeed, maybe even necessary, to know how to make words make particular sounds, nay, even rhythms, together, as training in listening, if nothing else….Ask any young composer of music if he/she hasn’t needed to adhere to the stanza, the musical phrase, the subtle notations for how long to hold a note, and so on, no matter how insanely wild the sounds. Jazz players with no formal training? There are only a few very good ones, and they hear it. They’ve listened so long and so hard that they hear it.”