I’m told if you score a bullet across its tip with a pocketknife, first lengthwise then across, your shot will penetrate its target cleanly, but ravage the organs inside. I thought of this when reading the blunt, clean prose of Melissa Febos in her new memoir, Abandon Me. —Carolyn Ogburn

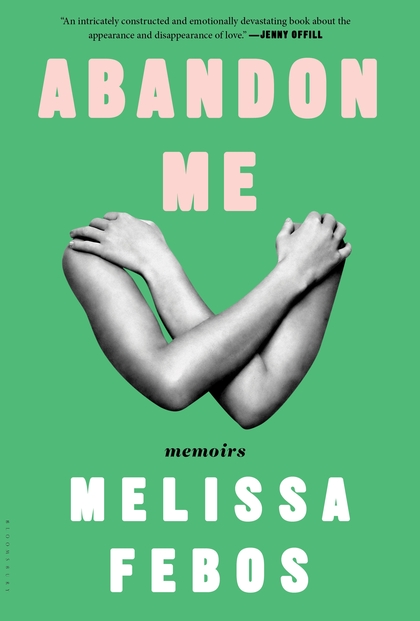

Abandon Me

Melissa Febos

Bloomsbury, 2017

320 pages; $26.00

.

I am told if you score a bullet across its tip with a pocketknife, first lengthwise then across, your shot will penetrate its target cleanly, but ravage the organs inside. I thought of this when reading the blunt, clean prose of Melissa Febos in her new memoir, Abandon Me. Her sentences are short, precise things containing emotional whirlwinds of joy and pain.

Melissa Febos is a writer and teacher who grew up in Massachusetts, earned an MFA from Sarah Lawrence College, and currently lives in Brooklyn. She’s on the faculty of Monmouth University and the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA); she serves on the board of VIDA: Women in the Literary Arts, and the PEN America Membership Committee. Her debut work, Whip Smart (2010) is a memoir of her work as a dominatrix. It’s also a story of getting sober, getting honest, and learning to live in her own skin. (It’s also funny: When her therapist asks her what a dominatrix is, Febos responds, “It’s really just one of the most well-paid acting gigs in this city.”) Her essays are found in journals, magazines, and online venues from The Rumpus to the Chronicle of Higher Education Review.

It can be hard to write about staggeringly painful personal life stories without sounding superficial, even trite. Students are encouraged to “write from the scars, not the wounds.” With the passing of time, the story may become more focused; resonances, patterns reveal themselves, and hard emotional truths can be drawn slowly to the surface. In other words, to write a simple truth about your own life, as memoir writers do, requires a great deal of craft. For all its risqué subject matter, Whip Smart was a more or less conventional memoir written by a smart, gutsy writer not afraid to explore her own history with honesty and poise. Febos would have been barely thirty when her first book was published. Now, seven years later, she takes more chances. Abandon Me is a deeper, riskier book.

Abandon Me opens with an epitaph from the psychologist D. W. Winnicott, “It is a joy to be hidden, and a disaster not to be found.” The book’s title, also the title of the novella-length essay found within, is both demand and plea: Abandon me. When written as a sentence—and it does feel like a sentence, both complete thought (the “you” understood, just off-stage) and punishment—the capital-A insists on being heard, a harsh, cruel word; while me is small and subjective.

The word abandon, Febos tells us, comes from the French, abandoner:

to give up, surrender (oneself or something), to give over utterly, to yield utterly.” Derived from a French phrase, Mettre sa forest a bandon, which meant to give up one’s land for a time, hence the latter connotation of giving up one’s rights for a time. Etymologically, the word carries a sense of “put someone under someone else’s control.

While no abandonment is complete in itself—and they’re all, here, ricocheting from the same impulse—the themes of absence, longing, and desire run throughout Febos’ relationships here. One of the abandonments she writes about is the departure of her father, when she wasn’t yet two. It wasn’t a disappearance: he was “a small suitcase that my parents unpacked for me as a child.” His name was Jon; he was “a career drug addict and alcoholic; he was Wampanoag; he played guitar.” She’d grown up knowing another man, here called the Captain, as her father, an Portuguese sailor whom she physically resembled more than she did her mother. The Captain left when she was eight.

In other words, Febos young life was marked by abandonment, the state of being the one left. But she’s also the one who leaves, the abandoner. Switch the words around: I abandon. I leave. “No lover had ever left me,” she writes. “I had spent enough years in therapist to know this was not something to brag about.”

The abandonment of the father mirrors that of the lover (and, in turn, mirrors that of the father), but it’s Febos’ abandonment of herself that is written most deeply throughout these pages. “Fear of abandonment begets abandonment,” Febos writes. “I gave myself away to solve the pain of his leaving and in doing so performed my own abandonment.” But along with biological bloodlines, Febos was parented by books, by story.

If a self can be said to resemble a house, Febos’ home is a library. The memoir begins with the Captain reading Ferdinand the Bull to Febos as a child, dissolving a paragraph later to the adult Febos and her lover reading Hemingway to each other in bed. Febos turns to books, stories, and television throughout the text range from Ferdinand to the Oxford English Dictionary, Salinger to Cervantes, Carl Jung to Scott Peck, William Blake to Salvador Dali, Jim Henson’s Labyrinth to the 1984 fantasy film, The NeverEnding Story. Febos’ story is stitched together with other stories, stories she’s claimed as her own. “To hold the memory of my history was to be searingly awake. I was not awake.” (178) So how much of this is true?

That’s the question everyone wants to ask the memoirist: What really happened? If you’re going to tell the truth, we demand evidence, facts, veracity. But to remember is an performance of the imagination, a deeply creative act.

She’s told us how to read her. In this 2016 essay called “Kettle Holes,” Febos writes:

We are all unreliable narrators of our own motives. And ‘feeling’ something neither proves nor disproves its existence. Conscious feelings are no accurate map to the psychic imprint of our experiences; they are the messy catalog of emotions once and twice and thrice removed, the symptoms of what we won’t let ourselves feel. They are not Jane Eyre’s locked-away Bertha Mason, but her cries that leak through the floorboards, the fire she sets while we sleep and the wet nightgown of its quenching.

We’re all, Febos seems to imply, creating ourselves out of ideas of ourselves, even while we’re living up to our nostrils in emotions that we didn’t choose, feelings (that, she reminds us, aren’t facts) that will not let us go. “Our selves are sometimes the only things over which we wield power,” she writes. “And our means of expressing it are sometimes chosen for us.”

At its most prosaic level, Abandon Me is the story of an affair: Febos fell in love with a married woman; they had a brief, tumultuous relationship, which ended messily. If you want to read the story for the plot points, you’ll find here a familiar story. Between its outlines, Febos weaves the threads of her renewed relationship with her birth father, and the women relatives with whom he lives. She pulls mythology, pop culture, history and philosophy into her narrative, as if surrounding herself with a posse of lively, intellectual friends.

But at its core, Abandon Me is almost wordless. “I had exiled large swaths of my history, and had been denied others. I had spent long stretches of time divorced from my body.” Paragraphs break off mid-thought, conversations are offered in fragments. It’s told in short chapters, often only a few pages long, even these broken into smaller units. Her friends don’t understand what she’s doing, why she doesn’t see them. She can’t explain it any better to her friends than she can to her lover. The best parts of this book make no sense at all.

That’s what I mean by ambitious. A lesser writer would have made her story make sense. She would have filled in conversations with dialogue, remembered what she wore; she would have distracted us from the gut-punch of pain that leaves us reeling with memories of our own. It’s not an easy book to read, not least because it demands that we read it with an honesty of our own.

There are places where Febos’ sentences are tonally repetitive, thudding, insistent. I longed for the distraction of a more lyrical line, and the wry humor that I remembered from Whip Smart. But maybe, more than anything else, I felt uncomfortable with my own memories of my own breathless affairs, the reminder that the most personal experiences are never ours alone, but are, despite all our feelings to the contrary, universal in their particularity. I can’t wait to see what Febos writes next.

—Carolyn Ogburn

N5

Carolyn Ogburn lives in the mountains of Western North Carolina where she takes on a variety of worldly topics from the quiet comfort of her porch. Her writing can be found in the Asheville Poetry Review, the Potomac Review, the Indiana Review, and more. A graduate of Oberlin Conservatory and NC School of the Arts, she writes on literature, autism, music, and disability rights. She is completing an MFA at Vermont College of Fine Arts, and is at work on her first novel.

.

.