x

Such has been my lot since childhood. Everyone read signs of non-existent evil traits in my features. But since they were expected to be there, they did make their appearance.

– Mikhail Lermontov, A Hero of Our Time

It’s a common misconception that men who have relationships on the Internet, with women who’ve just got out of psychiatric units, are creepy. But if there’s one thing I’m not, it’s a creep. Last week, when I helped my aunt Denise carry some videos into the Age Concern shop where she volunteers, she called me a strapping young man. That’s more like it. I’m good at scaring away burglars. If you live in the Hinckley area and you think you’re being burgled, don’t bother with the pigs, give me a call. I’m not in bad shape for twenty eight. Although last week, after urinating through the local paedophile’s letterbox, I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to run away fast enough. I wouldn’t normally give two thoughts to my own safety, but since I’ve started seeing this woman, I’ve started to think, what if I slip on some dog shit and the nonce catches up with me? And he’s with seven or eight of his nonce mates, and they’ve all got iron bars, and they put me in hospital? If I was in a full body cast, I wouldn’t be able to email Christine. That’s the woman I’m seeing. Well, seeing. I’ve hardly seen anything yet.

Whether I’m driving round the country in my lorry, or if I’m lying in bed with the polyrhythmic jive of Rhythm Is a Dancer still in my ears after deejaying at a wedding, all I’ve been able to think about lately is Christine and her knees. I imagine us chugging along, when I point out the window and say, “There’s that new service station I was telling you about.” While she’s not looking I reach across, lift the plate of food and squeeze her knee.

Here’s my latest missive:

Hi Christine,

Thanks for the new batch of snaps. Please keep sending this way. The thought of you missing a meal gets at me like DJs so up themselves they won’t take requests. You know the type. I don’t know who gets more out of these photos of salad — you or me.

The veggie burgers and quiches look like something I would pay good money to eat in a restaurant, even though I am not a vegetarian.

You’re clearly a talented chef. You should consider a career in the catering industry when you’re feeling well enough to look for work. If you need a reference, you know you can count on me. I attended a Hotel Management course at North Warwickshire and Hinckley College. And I used to work in the serving hatch at the Hinckley United football ground until I became the subject of one of the crowd’s bawdy songs.

Attached are some pictures I took of the 3,000 Years of Bread show at the Spittle Rooms on Thursday. The sound was sludgy and some bonehead security guard confiscated my kazoo. When I spoke to him after the show Mitchell from 3KYB said he still hadn’t got round to listening to the mix CD I gave him in Nottingham in February. But he will do very soon, he promised, and if he likes what he hears, there may be a slot coming up as their next tour DJ!

Later alligator.

Shockwave

She could probably be a star on Instagram with her photos, but she shuns fame and sends them to me instead. Last week she sent me photos of a pizza half-eaten on her Saturday-night knees in front of the TV, Yorkshire puddings covered in gravy titled ‘starters!’ (she’s from some northern slum), a box of popcorn balanced on her cinema knees, salads, curries, and lentil dishes I’m not going to pretend I know the names of. In the last few weeks our relationship has segued into a faster tempo — we email at least twice a day — but Christine still hasn’t shown more than the leg her food is rested on, from the bits of her lower thigh where the plate ends to the tip of her kneecap.

If that kneecap’s the tip of an iceberg, I’m the Titanic.

Mum calls me with a yap that’s indistinguishable from that of Cindy, her King Charles spaniel. “Can you hear me?” she yells up at me. “Go and help your father. Give him a hand with the hose pipe.”

The old man’s in his golf waterproofs unravelling the hose. I shut my curtains. Dark world in here. It’s my own party palace, Club Stig, and it’s always me on tunes. Requests on the hour, every hour. Shockwave in the house, your resident selector. Chock-a-block with club bangers and classic rock.

“Michael, help your father.”

She’s listening to the songs of Queen on the pan pipes. In the past I’ve got my own back on her by burning Ibiza compilations onto blank discs and swapping them for that guff she buys from the Body Shop. I turn up my 90s Megamix, but her screams come through the carpet, so I yell back down, “Shut up, you stupid bitch.”

She tries to get my attention from outside the door. Something about the noise, the smoke machine, the electric bill, and how she won’t be spoken to in her house. Who will be spoken to like that in her house, then? I certainly will not.

When she’s done yapping I breeze through the semi-detached and jump into my Vauxhall Astra. She follows me out to the front garden and does her standard irrational-woman impression. When I was a kid, they’d come from as far as Barwell and Earl Shilton to see her raving on the front lawn. On summer nights there would be fifteen to twenty kids from the neighbouring villages sitting on the grass bank by the bypass at six o’clock, when word had got round that she called me in from play. First she’d stand on the front step and scream, then she’d come out wearing her fluffy slippers and dressing gown that was too short, so it showed her legs all white and plucked. When she dragged me in, the kids would cheer my name. She always used to call me an imbecile for watching WWF wrestling, but she was the one who’d copy the wrestlers when she pointed at the kids and screamed, “You shut up.” Then they’d cheer as the door slammed behind me and I could still hear them while I was having my arse smacked. I give her the finger through the sunroof as I drive out the cul-de-sac and onto the A47.

It’s a five-minute drive to Halford’s at the Greenfields retail park, but I can get there in three. I park in the staff car park and lock my car with a flick of the wrist as I’m going through the sliding doors. I turn around and point to the back of my jacket with my thumbs. It says my DJ name, Shockwave, in white iron-on letters.

“Security to the front desk. Security to the front desk.”

Halfords is one of the last true friends of the car and haulage hustler. A petrolhead can browse the equipment with a sense of religious belonging, walking up and down the aisles, amazing novices with his scholarship of true bass speakers, exterior protectors, body styling, tints and strips, door-lock pins, exhaust trims. As the expert among the experts, I can enthuse about air horns, high-intensity discharge lights, badges and graphics, stickers and stripes. Often I’m called upon to intervene in a situation of tense customer relations drama, when Nigel — an expert in hi-viz clothing and the uses of WD40 but not much else — is out of his depth trying to assist with an engine-based query. If Maureen the security guard is unable to deal with inappropriate customer behaviour or slacking among the staff, I’ve been known to intervene.

“He’s about six foot tall, looks like a big jelly baby, and he’s got Shockwave printed on the back of his jacket.”

Nigel turns off the microphone but won’t make eye contact. “You’d better leave.”

“You talking to me?”

“You’re barred.”

“Why?”

“Calling a customer a nonce.”

“Is it because you’re a nonce?”

“No.”

“Is it because you’re a nonce, though?”

“No.”

“You’re a bit of a nonce yourself, aren’t you?”

“Security to the front desk.”

There’s a woman looking lost among the chamois leathers and polishes. In my Marks and Spencer’s jeans and boat shoes, I feel like Jeremy Clarkson on the deck of an aircraft carrier striding towards a lonely female mechanic. In slow motion, with Meat Loaf on the soundtrack.

“Hello, madam.”

“Hullo.”

“Shockwave.” I pause and let her take that in. “I help out round here.”

“Do you work here?”

“Looking for anything in particular?”

“My husband sent me out to get some wax.”

My hands are on my hips, and I’m shaking my head at a man delegating such a sensitive matter. I breathe out and make a hissing sound. “You’ve been stood there about ten minutes and nobody’s bothered to help.”

While I’m recommending the Armor All Shield Wax, Maureen the security guard — Slow Mo, as I call her — emerges from the end of the Car Styling aisle. Six months ago, I would have stayed and fought, but with Christine in the picture, it’s not worth it. I tell the woman I’m off to scout for new Top Gear locations along the Earl Shilton bypass. I palm her my business card.

SHOCKWAVE

DJ. Lorry driver. Vigilante.

Hinckley and Nuneaton area.

Call to arrange a DJ set, parcel delivery or security solution.

In the McDonald’s drive-thru I do some maintenance work in the rear-view mirror while waiting for my meal. My server is Jill, who I know without looking at her badge is a two-star employee. Franklin, my mate who worked here before throwing himself onto the M1 at Leicester Forest East, managed two stars before his tragic demise. If Jill doesn’t hurry up I may have to give her the benefit of my opinion.

“I could have bought a herd of cows and slaughtered them myself at this rate.”

“Pardon?”

“Ketchup and a straw please, Jill.”

“Can you turn your music down?”

“Loud?” I turn it up to eleven. The bass from DJ Luck and MC Neat almost knocks her off her feet. “That’s loud.” I point to the napkins and hold out my paper bag, having already started grabbing at the chips and eating them. “Shove them in there.”

I pull into my usual bay outside the Fitness First where I’m a member. While I’m eating my Extra Value Meal, I give my brother Marty a ding. He used to be in a rock band that were pretty big in the Hinckley and Nuneaton area. You might have heard of Bearded Woman. They played on one of the small stages at the Summer Sundae festival in Leicester. He had a job working for a video games manufacturer near Ashby, but now he’s the CEO of his own dating agency in Nottingham, catering to goths and rockers. The other day, when I was sprinting down Castle Street and I thought the area’s top nonce Geoff Doyle had called the five-o, I had no choice but to call Marty and tell him about Christine, so he could let her know in case something happened to me. But he’s not picking up. He’s probably on the driving range, warming up for his golf game with the old man.

While I’m sitting there, I get a new email from Christine. The subject is ‘Saturday brunch,’ and it’s a picture of a poached egg with hollandaise sauce on an English muffin. It’s balanced, as usual, on her knees. She’s wearing blue jeans, baggy and faded, the kind of thing I could imagine her wearing if we went to B&Q to get the materials for our deluxe soundproof shed.

I reply with a link to Chris’s Mix 19. It starts with the Artful Dodger featuring Craig David’s classic Re-Rewind from 1999, with me freestyling over it. This goes out to the coolest girl in the world, Christine. Helping you get over your problems. Don’t let the people take you away again. Here’s to your food diary. Eat, eat, eat and rewind. Eat a bit more. All those lovely cakes. Chocolate, biscuits, all them goodies, mmm. Don’t be scared. You’re not fat. You’re a beautiful woman. You can do it, baby. Shockwave’s behind you.

She replies with an emoji — two thumbs up.

Back at the house, Dad’s Rover 75 is gone from the driveway, so I’ve got the place to myself. I crank up another Megamix, but when Cindy keeps yapping outside my door and messes with my levels, I flip her a sedative. Ten minutes later she’s stiff as cardboard. I pick her up, tickle her belly, check if she’s still breathing then get back to the ol’ Messenger.

Yo, C. That muffin looks nice. Ever had them with bacon, sausage and brown sauce?

Yep had bacon and sausage but not for ages and never on a muffin, it’s so good, the hollandaise sauce, you can make it yourself, ever so easy.

We could make them together you know.

Listening to megamix 19 now, probs the best one yet!

What’s your favourite track?

They’re all good but if I had to choose, apart from your dedication (<3) track 14.

Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom! I want you in my room. We’ll spend the night together. Together in my…! Good choice. I listen to it when I’m stressed. That and Robbie Williams, Strong. You have to be strong, Chris. I know you think I live the life of Riley, always touring – stopping off at Road Chefs and playing the frooties when I feel like it, having two bags of chips at two consecutive road stops, doing what I like with my banging community of haulage hustlers – but the party palace is driving me up the wall. After I’d been up all night having it large, I only went and flipped DJ Slimy Fingers (my housemate)’s dog a sedative. Think I might have killed her. He’s in with some pretty unsavoury characters, so I need to lie low for awhile…

A few minutes pass. I consider sending her another message to check if she received my previous message. Patience, the wheel. While I wait for her to get back to me, I drop my jeans round my ankles and scroll through my Christine album to the chocolate fudge cake.

This has been approved by the lady herself. After we’d started messaging one another on the HAVOCA forum and she started emailing me her food photos, I told her snaps made the blood rush to my cock. She asked if it was her or the food that got me going. I told her it was the whole thing. She replied in seconds and said, are you feeling horny now, Shockwave, and I said yes. She asked if the photos made me want to touch myself. I said, if I did it right now, would you mind? If you say no, I promise I won’t. I’d never do it without your permission. She said no, I don’t mind. I asked if she wanted to see me do it, and she said yes.

I turned on my webcam.

Just as I get going, I hear Mum’s shrill voice. It could wilt a daffodil. I button my jeans and peek out the door, where Cindy’s in deathly repose. Mum’s coming up the stairs, moaning about the state of the bins. I wish I’d spiked her, but I don’t have access to chemicals that strong. When she finds Cindy, she screams, kicks my door, calls me the son of Satan, tells me to come out. Then she says if I come out, she’s going to murder me. Dad tries to pull her away from the door and says in his limpid hush that wouldn’t stop a kitten, “Cath, don’t be hysterical. There’s an emergency vet in Leicester.”

“She’s dead, Martin. That useless oaf’s killed her. I gave birth to a dog murderer. I should have asked for an exorcist, not a midwife. He never lifts a finger. He does nothing with his life but gawp at his computer and batters his brain with that music. When he does do something, it’s this. This. This!”

The usual.

When I’ve bundled socks, pants, changes of shirt and The World According To Clarkson in a holdall, I wait for her to scream herself out. Then I open my door and creep across the landing. So long, cruel house, with your menopausal wallpaper. I stop at the top of the stairs and listen to her psychotic breathing. The old man’s knelt by the witch’s chair, holding her arm, trying to stop her from going apeshit again. Dead Cindy’s in her lap. My foot presses onto the first stair. It creaks. Bleeding cheapo houses knocked out of plywood.

“Martin, he’s moving.” Shuffle of bunions. “I’ll disembowel him.”

I bustle downstairs. Lashes of mad hair rage from the living room. Piercing scream, arms spinning. I shield myself with the holdall, clocking a couple of blows over the bag, then a dig to the ribs and a kick from her rapier toenails. I shove-kick her backwards into Dad’s arms then pull the door towards me, jump out and pull it shut when I’m outside, locking her in. Rabid witch squashed against the frosted window. I leg it out to my car in the cul-de-sac, shoeless gravel feet, ow, ow. I’m reversing when the mad woman bursts out in a pale craze. Revving out of the second point of the turn, she collides with my back window, grabs at the locked door, snags the aerial, fingers scrape the roof. I release the clutch, down the juice. Trusty impeller spins in my turbocharger and I surge forwards. She’s thrown off and I feel ten tonnes lighter.

I stop at the entrance to the A47. It’s Saturday evening. Headlights scream across the pub-brawl night. Halfords shut at five. Besides, I’m barred. Will have to find another branch — Nuneaton or Coventry. Maybe they’re open later. Check the web on my phone: nope. Macca D’s? Twice in one day — no way, Jose. Pint down the Mill on the Soar. It’s a ten-minute drive but I can do it in seven. Not the local exactly, just a cosy hotel-restaurant on the way to Broughton, but I dip in for a pint every now and then. Familiar sights, tinkling lights, few frooties to boot.

I sit on a sofa with my Abbot ale, browsing the Halfords catalogue. Leaf through the Car Entertainment and Technology section. Christine’s still not online.

In the mental space to appreciate the Mill’s renovations, I plonk my pint on the coffee table and wiggle my toes underneath. Roadside pubs are my favourite. You wonder how a premises licensed to serve alcohol would stay afloat if you have to drive to it, but you forget how popular they are among the hidden elite: travelling middle managers, assistant headteachers and regional historians. Ukip and Tory voters mostly, the quiet majority, my type of people. I tell the couple of hotel guests from out of town, wearing their Marks and Spencer’s casuals, bonding over scampi, that it may not look very lively for a Friday evening, but you get a lot of people from Lutterworth coming here on their way to Hinckley, usually around lunchtime. They don’t understand the significance. Two towns not far enough apart to warrant a road stop? Such places thrive for one reason, I tell them. No, not even the convenience. It’s the glamour of anonymity.

I check my phone to see if Christine’s online. Still nothing.

When I’m done with my pint, I head back to the car, pull the breathalyser out of the glove compartment and blow a 0.42. I’m under the limit. While I’m sitting shoeless in the driving seat, Christine’s name flashes on my phone. She says she received my previous message. I tell her how everything kicked off at home while I had entered the Club Stig’s action area. She asks me where I am. Do I want to carry on? I tell her she read my mind. Let me reverse into a better spot — lucky, the carpark’s almost empty.

It started in my room, but if I get a message from her and I’m in a truck stop late at night, I’ll pull over and do it wherever I am. Lay-bys, service station toilets, in my car with the lights off. If I’m kipping over, I’ll set up on my lorry’s cot bed, where there’s a Bugatti Veyron poster and a cord light. I don’t get caught. I’m not trying to get caught either. I’m not a creep. The power in this thing is dangerous enough. I normally have one of Christine’s photos on the screen, maximised. Cake, polenta, salad, luring me through vectors. Like a lush rainforest through vinyl drapes. I look at the knees and the plate of food and think of her finger clicking the button on top of the camera, how it makes me feel a sudden jump. Sometimes, I turn Christine off. She doesn’t know, but I turn off the screen and whack myself off into the black void.

The phone’s in its cradle by the gear stick with the sound and video broadcasting. There’s light from the advertising board on the side of the pub. I scroll to the most recent batch of photos with my left hand, half an eye on the rear-view mirror in case somebody pulls in. On the 4.5-inch Samsung screen is a high-resolution photo of Christine’s chocolate cake, a dangling square orb. I swipe across — next — and it’s the spinach and ricotta parcel. Next. Banana in a bowl of custard. Next. Eggs benedict. Next, next, next.

In my mind, Christine’s cheering me on. I’m her sacrifice, cold as ice, yet hotter than burning rubber. I play music — a Megamix. I get in the zone and the boogie snake takes over. Christine, this goes out to you.

I make sure everything’s folded into the mansize Kleenex — I like how they call them ‘mansize’ when everybody knows what they really mean — and wrap it in a Tesco bag that I keep under the seat. This one’s full, so I tie it in a knot, get out the car and look for a bin. There’s not one outside, so I strut back into the Mill and ask one of the waitresses if they’d mind disposing of some tour debris. I fake a sneeze, wipe my nose with my finger and say, “It isn’t half dusty in there.” I swing the Tesco bag in her direction, but she backs away and says there’s a bin by the entrance to the hotel. While I’m there, I book a room for the night, and the manager gives me a key to a double room. I go back to the car and tell Christine that my Club Stig housemates are doing my head in — I dangle the keys in front of the camera — so I’ve moved into a hotel. It’s a hustler’s hangout, nobody would ask questions.

There’s a Wetherspoons breakfast at the foot of every mountain in life, I’ve told her before. We could stay a night here, a night there, whichever part of the country I’m called to. She can ride shotgun, take lunch on her knees on the seat next to me. We’ll jump on the beds of every motorway Travelodge, fill up on pancakes at every Wimpy and make the most of Pizza Hut lunch buffets. We can make mad orders: try limited-edition frappucinos, fill the salad bowl so high that the lid has to be squashed down, stack up on glossy weeklies, go wild on CD compilations. I’ll cover the bill.

She replies:

why don’t u come here?

I tell her, only if you insist. I don’t want to harm your recovery. Before I can tell her that I only have her best interests at heart, she says that we’ve been building up to this, haven’t we? All this time? Now I’m ready. I wonder when she decided this, and think to ask, but fear that I will put doubt in her mind. She clearly wouldn’t take such a decision lightly, being the kind of person whose mistakes cost her years.

No, I mean it, you can come here. I didn’t want to plan it else I thought I’d get scared and back out. Are you ready?

I’m ready, I tell her.

You’re not backing out now are you? You’ll come for me tonight?

Are you alone? I ask.

Not tonight I won’t be, not with you here.

Alright, text me your address. I’d put it in the sat-nav but I left it behind. Don’t worry, I know my way round.

I turn the key in the ignition and ram into reverse. I don’t bother to stop and look both ways at the entrance to the B4114, but feed the wheel through smooth hands, no crossing, booting through second, over-running third until I hit sixty.

A star in a reasonably priced car. Power.

All roads lead north. Sheffield to be exact, straight up the M1. I turn back on myself and within three minutes I’m on the motorway, throbbing with a pulse deep inside me. Past the bridge at Leicester Forest East, I feel the little bump in the road where Franklin’s bellyflop dented the concrete and had to be re-laid.

Now I live for the moments between departure and arrival. I don’t hear the Megamix so much as live inside it. Its beats are an interior rhythm that have been coded into my spinal cord, like some highly advanced vertebrate that evolved with its own soundtrack. The camera pans alongside me, flown by a helicopter traversing flat fields that occur only as a blur. I can’t help but think that I’m racing against Clarkson, James May and Richard ‘the Hamster’ Hammond in a romantic Top Gear challenge. They may have been kitted out with faster cars and TomToms, but this circuit can only be navigated by the satellite of love.

The Satellite of Love Dab Hands 2004 Retouch Mix comes on as the sign for Yorkshire appears, and it’s like I’ve been compiling a giant showreel in my mind. My life is taking shape. I want to chuck myself about in this perfect moment — bounce along to a 4/4 beat with pint in hand, surrounded by all the lads wearing short sleeves in nippy weather — but I mustn’t take my hands off the wheel. Stare ahead and let your right foot do the work, Shockwave.

I turn off the motorway and prepare for a moment that has already happened. It’s been storyboarded and timelined. Memories of me arriving to rescue Christine were rigged up ages ago. This is just the editing phase, and it’s happening while we’re still in production, but nothing can go wrong, as it’s already happened. The soundtrack has already been mixed. Glitches like forgetting to pack my shoes and sat-nav were written into the script, to make the challenge seem more believable and exciting. I am delivering my life to Christine. DJ sets and security solutions come as standard.

I’ll have no problem finding her address. I have to ask a couple of lairy youths hanging around suspiciously outside Bramall Lane football ground, but I know they’ll give me the wrong directions on purpose, so as I drive away, I crack a joke about how poor everybody is up north, then go the opposite way along the foggy backstreets of Ecclesall Road, where I find the perfect parking space right outside Christine’s front door.

I spend five minutes buffing my exterior. I’m a bit blotchy, but that’s good, it was my plan not to turn up looking like David Beckham, as it would be inauthentic after a challenge. I look at the front door and remind myself how to react when it opens. My entrance is inspired by ‘Dr.’ Neil Fox from the Magic FM breakfast show, when he cruised into Hinckley Asda to snip a ribbon for Loros. But if Dr. Fox is a morning coffee fix, bouncing eyes and treble voiced, Shockwave smiles with his eyes but not in a demented way. He’s cool and relaxed, he’s smooth and sensual, he’s drive-time.

There’s a bright bulb behind Christine’s beige muslin, the drape of choice for students and benefits claimants. The curtain’s about to go up. It’s nearly two hours since I told her I’d be there in two hours. One more look at the time. This is it then.

I get out the car door and — shit the bed — my foot crunches onto a sharp tin can. The rim digs into the arch of my foot and my big toe gets stuck in the hole. I hold onto the car roof for balance and try to dislodge the twisted metal while hopping on glass from the vandalised bus stop. I tug myself out eventually, pulling about half the skin on my big toe with it. I can feel blood from the graze soaking my right sock and glass shards digging into the left sole. But I don’t limp, because I’m hard.

I lock the car. The waist-high gate that needs a lick of paint creaks as I push through and walk up the three yards of slabs. Looking through the frosted glass windows in the door, I can see a couple of bicycles leaning in the hall. Christine hasn’t mentioned that she’s a cyclist. Maybe they belong to her housemates. I won’t hold it against them unless I find out they’re militant cyclists with cameras on their helmets.

It’s about dinner time. We’ll either share our first meal together here or at a Harvester I saw before the turning. It will be on me, of course. From now on, everything will always be on me.

I rap the door in a 4/4 beat. Knock, knock, knock, knock. I wanted you in my — life. A shape moves towards me, dark-haired and tall. The door opens and it’s a young bloke with bad skin and hair artificially straightened into a fringe, holding a can of Red Bull. He looks like somebody who pisses on the toilet seat.

“Is Christine in?”

“Who’s asking?”

“She’s expecting me.”

“You’d better come in then.”

When I’m inside I notice there’s a condom on my toe. Wet and greasy — it’s used — flapping on the dirty laminate floor like some sordid flipper. I flick it off under the bike wheel as I edge past the lad, muttering something about an itch. He closes the door behind us.

“Through there, on the left.”

A lad in his early twenties in a baseball cap, standing in the middle of the living room, points a video camera at me. “Are you Michael, otherwise known as Shockwave?”

On the sofa two lads in trackie bottoms watch a laptop connected to the camera. They’re the kind of people I’ve spent my life crossing the road to avoid — spotty and sniggering beneath Nike caps. I turn to leave, but the one who let me in shuts the living-room door behind him and leans back against it. I hope if I say that I’ve got the wrong address, I can give Christine a call and get her to meet me on neutral ground, because I don’t like her housemates.

“I think I’ve got the wrong house.”

He holds the condom between his fingers and dangles it for the others to see. “Is this yours, mate?”

The others laugh.

“It got stuck to my foot by accident. Have you got a bin? I’ll put it in the bin for you.” I go to take it off him, but as I do, he pulls a cricket bat from behind the armchair. I retreat to the back of the small, undecorated room, and the cameraman dances around me. I can see my own face on the laptop screen, scared and red, wobbling with the shake of the cameraman’s hand as he searches for the right close-up. While I’m looking at the screen, rapid goo slaps me in the face, stinging my eye. I peel the condom off my face and drop it in the disused fireplace where I’m standing.

As they laugh, the cameraman and the guard rush to confer with the two producers on the sofa. They watch replays of the condom striking me. They laugh again, louder, then play it again, asking for close-ups and pauses. “That’s it. Can you get a screen grab of the moment it hits him?”

They giggle at every bit of my humiliation.

“A second later, when it’s in his fingers, and he’s peeling it away, but we can still see his face. That’s the one.”

I rush to the door, but the guard jumps back into position and holds the bat over his shoulder, ready to swing.

“There must be a mix up,” I say again. “I’ve got the wrong house.”

“Shockwave, stop saying you’ve got the wrong house, mate.” The cameraman turns back to me. “What are you doing here? Do you know who we are?”

“Christine told me to come over. She texted me two hours ago. I can show you my phone. Are you her housemates?”

“How do you know Christine?”

“I don’t want to be filmed. Could you stop filming please?”

“He doesn’t like being filmed.” They laugh.

“Turn it off me. Turn it off now.” I palm the camera as it comes towards me, but the guard springs towards me with the bat above his head. I back myself into the corner with my arms raised, but the guard tells me to drop them else he’ll break them. I lower them slowly and he backs off.

“What’ll you do, Shockwave? Get your knob out and have a wank?”

“What you on about?”

“All that stuff you’ve done, it’s not going away.”

“What stuff? I’m here to see Christine, that’s all. If she’s not here, let me out.”

I move my hands towards the window, but one of the producers tells me in a bored voice that it’s locked. I believe him. I believe they were expecting somebody, but not me. They’ve got the wrong idea about who I am, what my life has been, and what my motives are. “Who are you? What do you want?”

But all they do is laugh.

“He’s clearly never heard of us,” the bored producer says.

“Right shame,” the cameraman says. “Because we know all about him.”

When I get out the car for real, I hope my nightmare is locked safely in the boot, where it will die in a head-on crash with reality. My foot lands safely on the can-free road. No used johnnies on my toe this time. The door puffs shut behind me. I resist the temptation to whistle I’m Coming Out by Diana Ross as I go through the gate and towards the terraced house where my future has been incubating. I push my nose up close to the frosted glass: can’t see any bikes in the hallway — a good omen. Just a milky glow from the kitchen, where I can only hope that Christine’s making a brew. I can’t stand here all night deliberating what to do, though, because I can feel the Red Bull surging through me and there’s no toilet near. Worst comes to the worst, I’ve got a baseball bat in the car. I could go and fetch it but that’s not really the look I’m going for. I flick my hand towards the door and then pull it away. I consider dropping a note through the letter box and asking her to meet me in the car, but that’s a bit creepy as well, like I’m trying to get her to go dogging, when that’s exactly the kind of thing I won’t stand for.

I give the door two gentle raps then two harder ones. The light in the hallway comes on. Somebody in a white sleeveless top with long hair, a bit shorter than me, a human female in jeans crumpled over the knees is coming to open the door. The window frosting distorts, but I’m pretty sure I recognise those knees. Now she’s too close, I can’t see down as far as the knees. I should probably step away from the glass so she doesn’t think I’m a window licker. Here she comes. The door swings open. Whatever happens now, Shockwave, you’ll have to freestyle.

—Lewis Parker

x

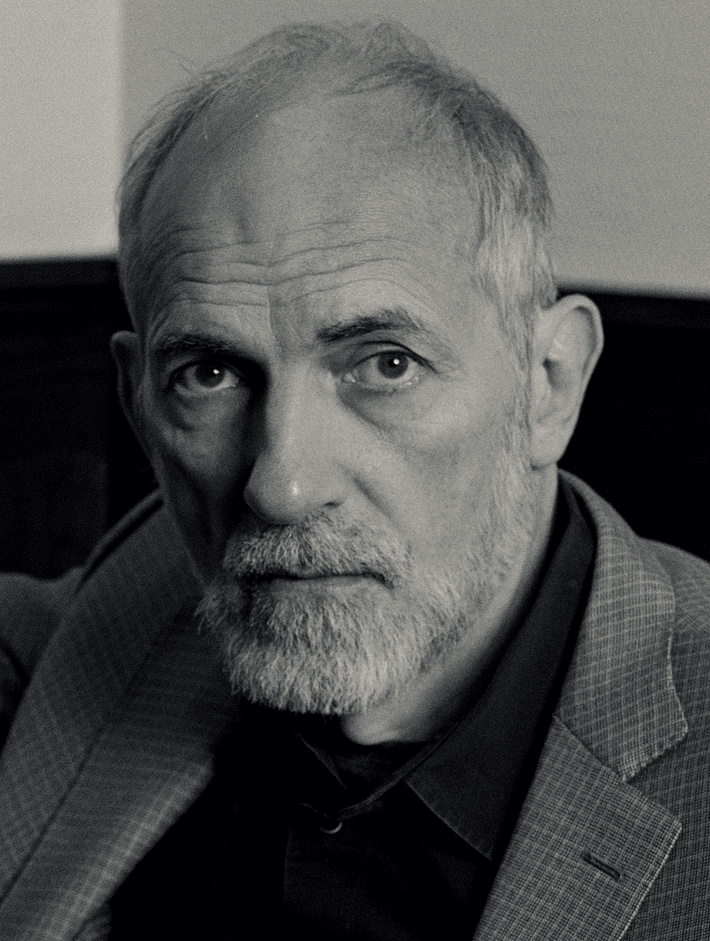

Lewis Parker is a writer of fiction, poetry and journalism who is trying to get out of London. A hand-typed book of his poems, Suicide Notes, collects the best things he’s written while working as an écrivain public in the streets and at festivals during the last year. His prose has been in the Guardian, New Statesman, Dazed & Confused and Minor Literature[s], and he has taught at Kingston University in England.

x

x