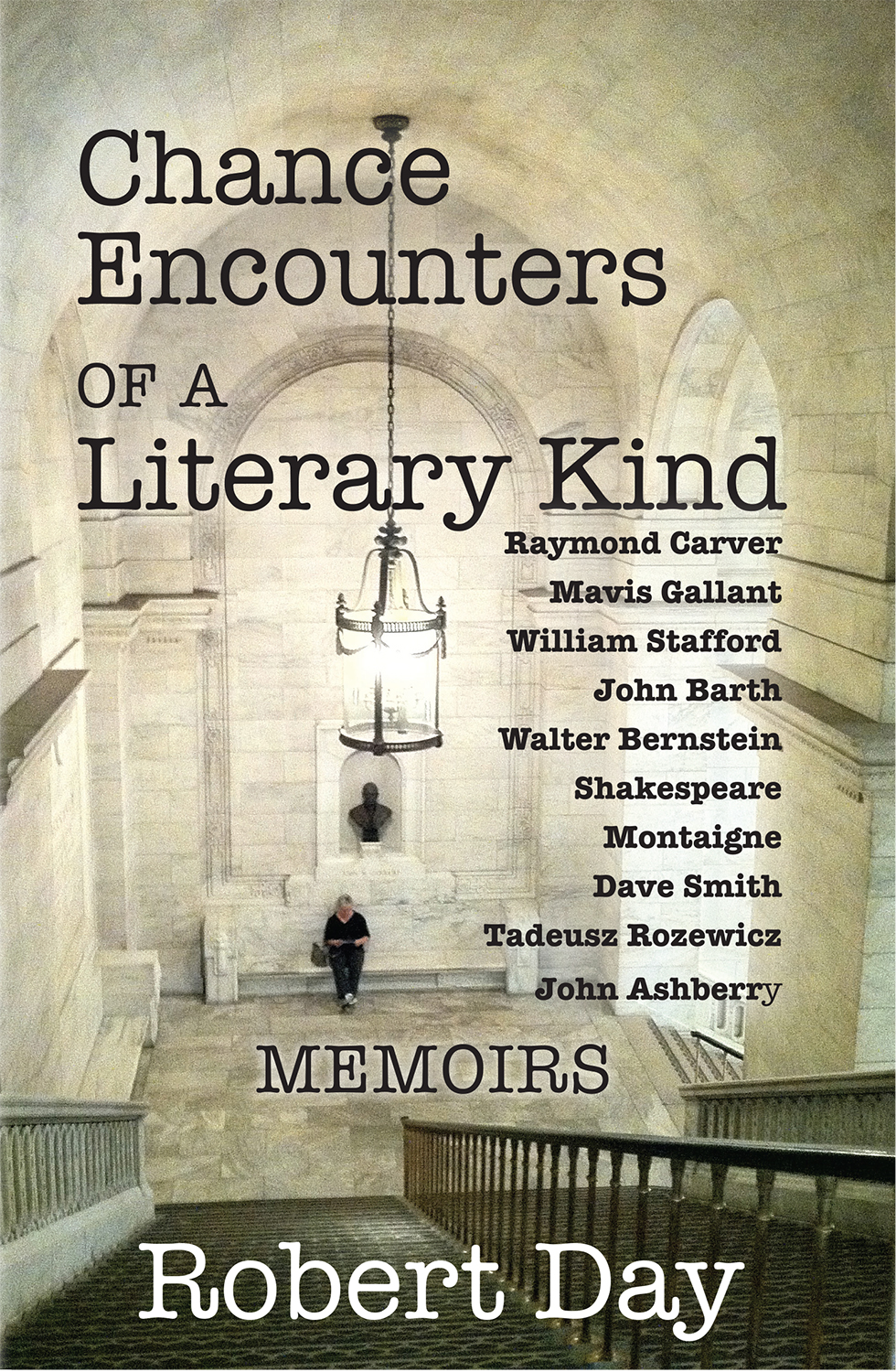

Numéro Cinq is always an adventure, a game of firsts. The first this, the first that. Now Robert Day‘s essay series Chance Encounters of a Literary Kind is being published (the end of the month) by Serving House Books and that is a first of a high order, the first ever book composed entirely of work that appeared in Numéro Cinq first (you can see I am obsessing on the word “first”). This is a proud moment for the whole community and an inspiration to the many who have contributed regularly and brilliantly to the magazine. I foresee more such NC-inspired books. (Actually, Robert Day’s novel, Let Us Imagine Lose Love, first serialized on NC, will be published in the fall as well, but I will do a separate announcement about that at the appropriate moment. The man is on a roll!)

I wrote an introduction — entitled “Exit, Pursued by a Bear” — for the Serving House Books edition, an honour and a pleasure (he opines) that you all get to share right now.

§

Exit, pursued by a bear

Robert Day and I met something like 35 years ago in a University of Iowa classroom. He was the teacher, I was a student. He strode into the room and proceeded to the blackboard where he wrote, in large capital letters, from one side of the room to the other: REMEMBER TO TELL THEM THE NOVEL IS A POEM. Outside of class we got to know each other a bit. He once said, pressing the elevator button instead of climbing one slight of stairs, that if God had meant us to use stairs he would not have invented elevators. I was on the cusp of a truly disastrous relationship just then. Day said to me, “Get out of there. For every day you spend with her now, it’ll take you another year to get out of it.” Ask me if I listened to him. One afternoon we spent kicking tires at a Jeep dealership. And one day he talked to me about the novel I was working on, a conference that must have lasted all of 20 minutes but somehow managed to open up the novel and show me its hot, beating heart, which hitherto had failed to reveal itself to me. That was a lesson I did listen to.

Now, many, many, many years later we have congregated again through the magical intervention of the Internet and the online magazine I materialized Numéro Cinq. We hadn’t been in touch in years; we still haven’t actually seen each other since 1981. But we continue to exert gravitational force upon each other’s lives in ways that are astonishing and delightful. The long and short of it is that I began to publish Robert Day. A short story first. Later the story became a novel. I published the entire novel. Then I published a memoir about his mother, a tender, sweet essay about her suspicion of the French, Day’s love of Montaigne, and the summer she died while he was traveling in France.

Then Day invented a new form, the Chance Encounters of a Literary Kind essays, brief, whimsical, sometimes touching, reminiscences about his brushes (often friendships) with literary greatness. The first one he wrote and tried out on me was about the poets John Ashbery and Tadeusz Rozewicz. He didn’t meet them; they met in his mind, and in a conversation with a friend over a kitchen table in Kansas. But the collision was sparkling in its reverent irreverence and the insights spawned in the erotics of juxtaposition. But it was also airy, gossamer-thin, a playful and informal thing, a little jeu d’esprit that took itself not very seriously, yet with flashes of seriousness and wit. Day asked me if I wanted more of these. He projected a series. He made a list. He wrote: “I’d like to keep the “Chance encounters” real–that is, what I stumble into or on to as I lead my literary life; there should be x of them the rest of the year because I poke around in these matters often these days, and, like any fiction writer, stories (and chance literary encounters) happen to me.

I have my favorite moments. Day and Raymond Carver quoting Jack London back and forth to each other. Day’s sweet evocation of the life-philosophy of poet William Stafford, who once advised his young daughter, “Talk to strangers.” This is in an essay that goes on to ponder our current Age of Fear, the prevalence of surveillance, and our willingness to submit to precautions that cheat us of human relations.

I also adore Day’s piece on screenwriter Walter Bernstein, especially Day’s expert interventions in an early script for the movie The Electric Horseman. Day being from Kansas, Bernstein considered him the expert on cowboys and horses. “Somehow Walter had learned the word hackamore (probably from an East Coast riding friend) and so I had to take the hackamore off all horses and put bridles and bits back in their mouths.” And, of course, the “Exit, pursued by a bear” stage direction from The Winter’s Tale that pops up unbidden and like fireworks in Day’s essay on Sarah Palin and going to see a production of Coriolanus.

The buzzword these days for someone who wanders about poking idly into things (and being brilliant and witty about them) is flâneur. But when I read Day’s essays I think, not of Walter Benjamin, but of the waggish early 18th century essays of Joseph Addison and Richard Steele and the journals they published, The Tatler and The Spectator, whose purpose it was “to enliven morality with wit; and to temper wit with morality.” Day’s essays are intelligent, literate conversation at its best—all too rare these days—written with aplomb in the author’s trademark amiable and self-ironic style.

—Douglas Glover