A Parsi friend of mine was talking about a recent death in the family and casually mentioned something about the custom of boxing up bodies and flying them back to Mumbai for exposure in the Tower of Silence. My ears pricked up instantaneously at the phrase Tower of Silence, which seemed at once poetic, terrible, awe-inspiring, mysterious and uncanny. It seemed like a phrase out of fairy tales, not something you hear in a phone conversation with a friend on an April afternoon in 2015. It seemed I had rocketed back into ancient things, when the world was magic and the great god Pan was not dead, or, as Isak Dinesen once wrote, when we lived on an the earth not yet “abandoned by angels.”

So I did the usual reading tour of the Internet. The Parsi are Indian descendents of the once great Zoroastrian religion centred in what is now Iran. There are Towers of Silence in Iran as well as India. Funerary customs are as diverse as the human race. At some point, the Zoroastrians began the practice of exposing their dead to vultures and the elements in circular towers built on hills in lonely desert places. A particular design and rituals evolved around these structures, based on the poetic idea that death was a triumph of evil over good, a rushing in of the death demons that made the body ritually unclean. It had to be got rid of as quickly as possible and not touched except by ritual bearers. The practice of using Towers of Silence has died out in Iran but still exists in India, though modern chemical use in agriculture has almost cleaned out the vulture population. Vultures used to be able to pick a corpse to the bones in a couple of hours.

Funerary customs are fascinating and excarnation is not uncommon. Tibetan Buddhists are famous for their Sky Burials. The North American Comanche used to expose their dead on platforms. Several Native American cultures I am aware of practiced some form of let-rot-and-clean-the-bones ritual, with reinterment after in a charnel house (Natchez) or ossuary (Huron). And our own practice of cleaning out the body, infusing it with preservatives, dressing it in nice clothes, and burying it in a box can seem, in some views, pretty icky. (Let us not mention the contemporary industrial solution: cremation in a furnace.) Face it: Many contemporary cultures have lost the ability to make dramatic symbolic gestures toward the cosmic mysteries that enclose us.

The Wikipedia article on Towers of Silence is full of poetry, words in languages I do not know but wish I did: dakhma, cheel ghar, astodan, doongerwadi. It leads to a great 1928 article “The Funeral Ceremonies of the Parsees: Their origin and explanation” by Jivanji Jamshedji Modi, wherein he writes things like (this is in the footnotes — I am a footnote fetishist: the poetry is in the footnotes — also I am aware that dogs are tangential to the subject at hand, excarnation customs among the Parsi, but the words are beautiful and there is mention of a spotted dog):

It appears from the customs of several ancient nations that the “dog” played a prominent part in the funeral ceremonies of many ancient nations.

(a) As said above, as in the Avesta so in the Vedas, we have a mention of two four-eyed dogs guarding the way to the abode of Yama, the ruler of the spirits of the dead. (b) Among the ancient Romans the Lares of the departed virtuous were represented in pictures with a dog tied to their legs. This was intended to show that as the dogs watched faithfully at the door of their masters, so the Lares watched the interests of the family to which they belonged. (c) The people of the West Indies have a notion among them of the dogs accompanying the departed dead. Compare the following lines of Pope:–

“Even the poor Indian whose untutored mind

Sees God in clouds or hears him in the wind

* * * * * *

thinks, admitted to you equal sky

His faithful dog shall bear him company.”

As to the purpose, why the “sagdid” is performed, several reasons are assigned: (a) Some say that the spotted dog was a species of dog that possessed the characteristic of staring steadily at a body, if life was altogether extinct, and of not looking to him at all, if life was not altogether extinct. Thus the old Persians ascertained by the “sagdid”, if the life was really extinct. (b) Others, as Dr. Haug says, attributed the “sagdid” to some magnetic influence in the eyes of the dog. (c) Others again connected the “Sag-did” of a dog, which, of all animals, is the most faithful to his master, with the idea of loyalty and gratitude that must exist between the living and deceased departed ones. (d) Others considered a dog to be symbolical of the destruction of moral passions. Death put an end to all moral passions so the presence of a dog near the dead body emphasized that idea. Cf. Dante’s Divine Comedy (Hell. C.I. 94-102. Dr. Plumpter.)

“For that fell beast whose Spite thou wailest o’er,

Lets no man onward pass along her way.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Many the creatures are that with her wed,

And will be more until the Greyhound come,

Who with sharp agony shall smite her dead.”

Here the Greyhound is considered as the deliverer of Italy. He is the symbol of the destroyer of the passions of sensual enjoyment, pride and avarice which are represented by the leopard, the lion and the wolf.

But the best piece I found was in the amazing Italian-Parisian online architecture and culture magazine Socks, which ran an essay and photos on the Towers of Silence in 2012, upon which I cannot improve in the 20 minutes I have allotted myself for writing this.

Zoroastrianism traditionally conceives death as a temporary triumph of evil over good: rushing into the body, the corpse demon contaminates everything it comes in contact with.

The flesh of a dead body being so unclean it can pollute everything, a set of rules had to be created in order to dispose of the corpse as safely as possible: as the natural elements of earth, air and water are sacred, the corpses were not to be thrown upon the water or interred. Cremation was also forbidden, as fire is the direct -purest- emanation of the divinity.

Hence a complex ritual was developed, in which the corpses would be eventually exposed to birds of prey and thus devoured, in a final act of charity.

After death every division of class and wealth disappeared, for all deceased would be treated equally.

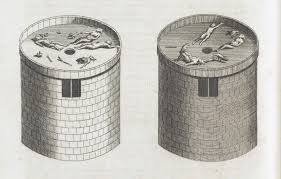

A proper architectural typology was invented solely for the purpose of burial’s ritual: transported in the desert by nasellars (traditional zoroastrian pallbearers), the bodies of the deceased were then carted onto sandstone, forbidding hills, to be eventually disposed on cylindrical constructions called Towers of Silence.

How strange to think that burning a corpse was not acceptable because fire is “the direct – purest – emanation the divinity.” To my thinking, having the Secular (body) consumed by the Divine (flames) sounds like a spot-on symbolic gesture. It would take some real convincing for me to leave out the body of someone I loved for the vultures to rip apart. I like the idea of my survivors putting me in a furnace and turning me to ashes, the faster the better, especially if it goes along with the belief, still strong in southern Mexico, that the dead come back for All-Souls Day and eat whatever favorite food you’ve left out for them on the home altar. Interesting read, Doug – thanks.

🙂 Vultures get a bad rap in our culture.

It is interesting how one cultural syntax can look just plain illogical to another culture. Strangeness and difference are pretty valuable categories, it seems to me. They lead to questions and then, maybe, some understanding. So I like your reaction. But I myself am uncomfortable with blazing furnaces.

I look at the birdfeeder outside my kitchen window now and think “Tower of Silence.” 🙂

Just a modern-day reality – nowadays some folks’ apartment balconies are perilously close to the Towers – on the vultures’ flight paths – and you may me able to imagine the problems this causes. Heard this from a Hindu colleague from Mumbai whose apartment is so situated.

Yes, I also am pretty uncomfortable with blazing furnaces– remain haunted after almost 15 years by the groaning sound of the furnace at the crematorium when my mother was cremated. To have my body feed the earth or its creatures seems to me like returning it to the source.