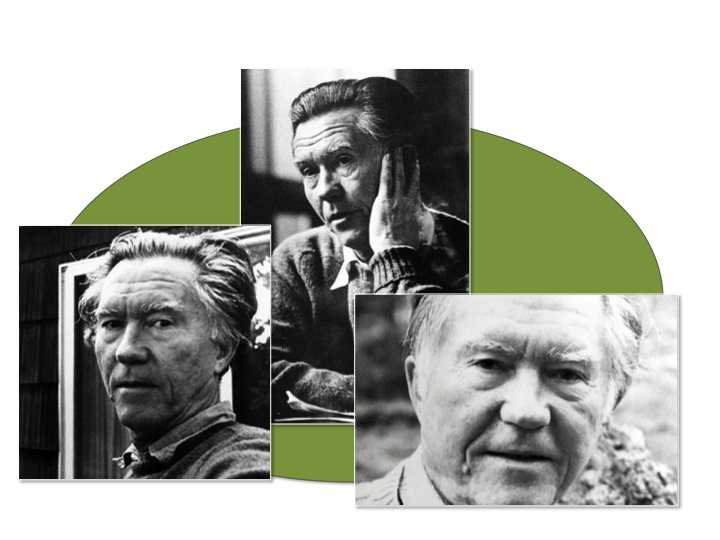

William Stafford via the Poetry Foundation and others

William Stafford via the Poetry Foundation and others

At the library of Congress in 1994 there was a memorial tribute to William Stafford, the brilliant American poet who, in 1970, had been what is now called the Poet Laureate of the United States.

There were the usual accolades: Bill Stafford was a poet whose plain language fitted his flatland Kansas sensibility. He was a man who thought peace (Stafford was a conscientious objector during World War Two) was good; war was wrong. There were other kind words. About the self-evident and the oblique stories in his poems. About those poem’s gifted reticence. Then something extraordinary was said. One of his children, his daughter Kit I think, told us of her father’s repeated advice to them as they were growing up: “Talk to strangers.”

By chance I was Bill Stafford’s student in the sense that I learned from him about writing and life: Do it all and do it all now. The threshold is never so high as you imagine. The beginning may not be the beginning. The end may not be the end. These aphorisms applied not only to his craft and mine, but to the way we lived. And there was a sense in what I learned from Bill Stafford that the two might not be easily separated.

Not far where I live in Kansas (and about the same distance from where Bill Stafford grew up) there is a high school in a town of roughly a thousand that has a video security system of which they are especially proud. I had been asked to be part of a literary program there (my talk was on Bill Stafford), and came to know about the surveillance cameras because I saw one posted in the room where I was speaking. Later, I saw the black and white glow of the monitors in the school’s office. I watched as the system projected pictures of the gymnasium (empty on this autumn Saturday); various hallways (also empty); our meeting room (adults milling around drinking coffee and eating donuts); and finally a shot outside the school: the wide Kansas prairie as background, a small Kansas town in the foreground.

One of the school’s officials and a parent stopped to say that you couldn’t be too careful these days, what with Columbine and Amber alert. Bad things happen in schools. And out of schools. Better to be vigilant than be sorry. When they left, I could see them on the monitors as they walked across the buffalo grass lawn to where they were parked. They talked for a moment over the bed of a pickup truck, and then drove off, safe, I suppose, in the knowledge that someone might have been watching them.

Over the years Bill Stafford and I wrote back and forth: letters, post cards, copies of our work sent to one another with inscriptions. As he was one of the most prolific poets of the 20th century, I got plenty more of the latter than did he. But no matter how far apart we were, Bill in Oregon and me in Kansas or in Europe, he would sign off with something like “Adios” or “Cheers”, and then, as if we were just across the pasture, he’d note: “And stop on by.” My sense now is that when I’d get to him, windblown and dusty from the walk over, he’d want to know if I’d met any strangers on the way, and what stories they had to tell.

Have we become an America where it is stupid to give the same advice to our children that Bill Stafford gave his, and where stop on by means please don’t? Have we come to believe that surveillance cameras in the high schools of tiny prairie towns will teach our students the eternal vigilance they’ll need to live in towns beyond their own? Or in their own? What with Columbine and Amber alert. Or is the answer from Bill Stafford’s poem Holcomb, Kansas?

Now the wide country has gone sober again.

The river talks all through the night, proving

its gravel. The valley climbs back into its hammock

below the mountain and becomes again only what

it is: night lights on farms make little blue domes

above them, bring pools for the stars; again

people can visit each other, talk easily,

deal with real killers only when they come.

Or are we all real killers?

There may be no reclaiming Bill Stafford’s vision of America, but once upon a time, in his plain voice, didn’t he speak for you?

— Robert Day

Robert Day is a frequent NC contributor. His most recent book is Where I Am Now, a collection of short fiction published by the University of Missouri-Kansas City BookMark Press. Booklist wrote: “Day’s smart and lovely writing effortlessly animates his characters, hinting at their secrets and coyly dangling a glimpse of rich and story-filled lives in front of his readers.” And Publisher’s Weekly observed: “Day’s prose feels fresh and compelling making for warmly appealing stories.”

.

.

What a lovely, thoughtful essay this is. I believe that, yes, we still need to tell our kids to talk to strangers. Maybe we can’t reclaim that old vision of America, but we damn well need to knock down a lot of walls of misunderstanding. How better to do it that to say hello and go from there? And now I need to go look for some William Stafford on my bookshelf.

All human beings, and I mean ALL human beings, have the potential to be “real killers” (and I have to ask: “real” as opposed to what?), given the right triggering circumstances.

I find it interesting to see how many crimes that may have gone unsolved in the past, are helped to be solved these days by evidence acquired from security cameras. I suspect the victims of crimes, and/or their families and friends appreciate that when it happens. I wonder what might have resulted in terms of solving the case, if there had been security cameras in place along the route that Etan Patz took to school in New York City on the day he disappeared.

Of course, the significance of Holcomb, Kansas is that it is the location of the “In Cold Blood” murders.

Yes, people should talk to strangers in appropriate situations and settings, but people should not ignore their gut feelings when approached by strangers either. It’s not easy to not view the past through rose-colored glasses.